You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

Late last year, Aaron Huey and I met at his favourite coffee shop in Seattle (the only coffee shop in the city without WiFi, as far as I know). During our chat, his phone was buzzing; on the line was Emphas.is finalising the details of his Pine Ridge Billboard Project pitch.

PINE RIDGE RESERVATION

Ever since Huey’s powerful and viral TED talk last year, he’s been inundated with inquiries from people wanting to get involved and contribute. Huey admitted to being conflicted by his unexpected propulsion into the centre of a nebulous political energy, partly because he doesn’t have all the answers and partly because his work still doesn’t sit well with some of the Lakota community. Understandably, some Lakota don’t want images of broken homes and broken bodies to be consumed by white America. Still, Huey has the faith of the majority within the Lakota people.

With a story so large and important – and solutions so complex – Huey was unsettled with the status and future of his Pine Ridge documentary work; he had not pushed the political issue as far as it warranted. From his Emphas.is pitch:

I have been documenting the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation for the past six years. Recently I have realized how inappropriate it is for this project to end with another book or a gallery show. […] Your involvement will help raise the visibility of these images by taking them straight to the public—to the sides of buses, subway tunnels, and billboards. I want people to think about prisoner of war camps in America on their commute to work. I want the message to be so loud that it cannot be ignored.

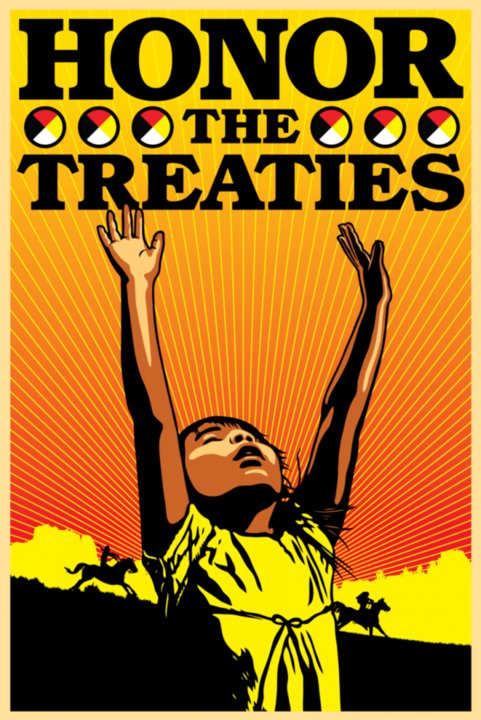

Emphas.is has given Huey, the Lakota people and us the opportunity to see and react to the work in unmissable public locations. It puts it in the face of D.C. politicians. Huey has enlisted the help of Shepard Fairey and artist and activist Ernesto Yerena who created visuals for the Alto Arizona campaign.

Source: http://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/~rfrey/329treaties_and_executive_orders.htm

PRISONER OF WAR CAMP #344

Huey’s photographs depict high unemployment, broken families, alcohol abuse and life expectancy lower than that in Afghanistan. The statistics are shocking.

But more than that, Huey’s photographs show the legacy of the lies and broken treaties of the US government stretching back over a century. If the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) had been observed, then the Lakota and associated Sioux tribes would own land stretching across five states.

To refer to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation as a prisoner of war camp may seem incendiary to some, but this is how many of the Lakota see their existence. The Black Hills have been stolen and the Lakota live on the most infertile land fenced in on all sides by an encroaching dominant culture that they’ve predominantly experienced as oppressing and damaging. The solutions are not simple, but awareness and a will to action is.

Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is prisoner of war camp #344.

EMPHAS.IS

I have offered what support I can to the new crowd-funding platform Emphas.is with articles here on Prison Photography and for Wired.com. Three of the online critics I respect most (Colin, David and Joerg) have also put their weight behind it. I am chuffed to see Aaron’s proposal off the ground and I’d ask you seriously to consider funding the Pine Ridge Billboard Project.

Mock-up of a wall installation using 24x 26″ posters, proposed Pine Ridge Billboard Project

OUTLETS FOR ACTION: Throughout the campaign a website honorthetreaties.org will be formed. Aaron will build the site as a point of reference for those who want to know more about the history and the (broken) treaties of the Sioux and other tribes. There will be direct links to assist grassroots Native non-profits in places like Pine Ridge.The first partner is Owe Aku.

More on Aaron’s blog here.

Buy a 18×24 print signed by Shepard Fairey and Aaron Huey to support the project!

Children of the family Raaymakers, hit by the crisis, getting help thanks to an action of magazine Het Leven. Best, The Netherlands, 1936.

The National Archive in The Netherlands just published a 30 image set on the theme of poverty.

The strength of some of the images blew me away. (Click any image for a larger view) The set spans nationals and eras so this isn’t a photo essay, just a moment to reflect. Through history, photography has indulged the upper classes, but how has it treated the impoverished? I don’t have the answers, just a meandering of a visual train of thought.

Children with scars and with gazes that cut through time …

Irish tinkers: mother and child in front of improvised tent, 1946

… and children slowly erased by time.

Poor German miners’ families eating at a soup kitchen, 1931

Jobs programs that have adults digging dirt like children digging beach sand …

Unemployment relief program in Schagen, Netherlands, 1967

… then, poor people who have carted each other across cobbles …

Woman transported on a hand-cart, Amsterdam, 1934

… and those that sleep beneath them.

French man spending a night under a bridge, catches a glimpse of photographer Willem van de Poll, date unknown.

Men have begged for the charity of the richest …

Man begs for money from George V (1865-1936), Epsom Downs, Derby Day, 1920.

…but usually received from the humblest.

Soup kitchen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1917

Poor people have been asked to rent dentures …

Man bites down on available dentures for hire, United States, 1940.

… and they have been made into leaders …

Dutch tramp who became a politician, Amsterdam, 1921

… and in so much as the poor man is the worker, they’ve seen it all.

Worker sweeps the floor in the New York Stock Exchange following the Wall Street Crash, 1929.

More images can be seen within the Collectie Spaarnestad: www.spaarnestadphoto.nl

Bettina von Kameke‘s series Wormwood Scrubs is a reflective look at the communal life of prisoners inside one of Britain’s most notorious prisons.

Wormwood Scrubs (Her Majesty’s Prison) is well known in Britain through both popular culture and sporadic news stories about the latest infamous prisoner. It is a institution everyone has heard, some would claim to know about, but in fact only a few truly know. Those few would be the staff and prisoners.

Von Kameke says:

“I was surprised at how respectful the interaction between staff and prisoners was. Of course I was aware that there is drug-dealing inside and it is a hard prison. I could feel the intensity and harshness of the energy… I reflected it in the sadness, heaviness, anger and frustration through the expressions on their faces. But the objective is to show the humanity in the system.”

I am impressed by von Kameke’s awareness (and depiction) of communal living.

“I question and explore the interior and exterior conditions, means and forces, which make a communal life sustainable. My photographs disclose the aesthetics of an enclosed community, which I carefully observe through the viewfinder of the camera.” (Source)

Prison jobs and recreational time are what make incarceration sustainable, and by that I mean as free from waste and repetition as possible.

Prisoners never make direct eye contact with von Kameke’s lens; she shoots as if she is not there. This, I suspect, has a lot to do with the amount of time she spent in Wormwood Scrubs; she spent over six months on the prison wings.*

She and the prisoners probably did have relationships, but they are not the subject of von Kameke’s photography; attentions are elsewhere … apparently.

Between von Kameke and her subjects is acceptance and restraint, almost to the point of collaboration. It cannot be overstated how difficult this is to achieve in a prison environment when everyone potentially has something to pursue and gain through interactions.

One final thing to note is the overlap in atmosphere between Wormwood Scrubs and von Kameke’s earlier series Tyburn Tree, which depicts the Benedictine Nuns of the Tyburn Tree Convent, London. Communal living within total institutions can be both enforced and voluntary.

Wormwood Scrubs is on show at Great Western Studios, 65 Alfred Road, London W2 5EU until March 11th.

More images at the Guardian.

* I always contend that the best prison photography projects result from a long term engagement with the subject. Von Kameke’s Wormwood Scrubs bears out this thesis oncemore.

Ara Oshagan sat down for an interview with Boy With Grenade to talk about his project Juvies from the California Youth Detention system. Oshagan talks about “access, his process and the state of documentary photography today.” It’s long but parts make good reading.

“There is a certain pragmatism in my outlook. I knew I could not have access to these kids outside of the limited access that I had when I went in. So I did not worry about that. I made sure that I was totally ready—physically and mentally—when I did spend time with them, to make the absolute most of that time, to be fully in the “space” with them, to have a clear mind, to connect as much as possible, and hope that this connectivity will translate into good photographs.”

“To make good photographs, I feel, one must create a good process. Photographs can never be an end; they necessarily must be a byproduct of an experience, a process. That connectivity with your subject matter must be present. If you go into a situation with the sole purpose of making “good photographs” you will invariably fail. Or at least, I will.”

Read the full interview.

I’ve written about Oshagan’s Juvies on Prison Photography once previously.

Photography and fingerprinting room.

David Moore has an uncanny knack of gaining access to sites most photographers might think are beyond reach.

In the Summer of 2009, Moore took advantage of a short-window of time during which the cells inside Paddington Green Police Station sat empty. The survey Moore completed – a series entitled 28 Days – was the first foray into this infamous jail. Prison Photography is proud to publish these images for the very first time.

[Keep reading below]

Chair.

Forensic pod.

Paddington Green Police Station is structurally banal. Constructed in the late sixties, its functionalism is belied somewhat by a concrete-lovers facade. For Britons, Paddington Green means one thing: Terrorism. Built into and underneath the station are sixteen cells and a purpose built custody suite; extraordinary hardware for a police station, but not for the interrogation of high-level terror suspects.

In the 1970’s many IRA suspects were incarcerated at Paddington Green prior to appearing in court. At that time, the period of initial detention was up to 48 hours, this could be extended by a maximum of five additional days by the Home Secretary. (Prevention of Terrorism Act, Northern Ireland, 1974). British terror legislation was not renewed until the Millennium.

The Terrorism Act of 2006 increased the limit of pre-charge detention for terrorist suspects to 28-days, hence Moore’s title for the work.

Originally, the Labour Government and Prime Minister Tony Blair, had pushed for a 90-day detention period, but following a rebellion by Labour MPs, it was reduced to 28-days after a vote in the House of Commons.

[Keep reading below]

Control room.

Chair, police interview room.

Holding cell.

In 2005, Lord Carlile (a hero of photographers, as a key person in reversing abused UK police stop-and-search procedures) was appointed independent reviewer for the government’s anti-terrorism legislation. His team visited Paddington Green in May, 2007 and issued a damning report on its inadequacy as a modern facility for the detention of humans for such extended periods.

The facilities […] were designed when the station was built in the late 1960s in order to deal with terrorism suspects from Northern Ireland – a far different threat from that faced from international terrorism today, in terms of scale and complexity. The main deficiencies of Paddington Green are as follows:

* there are only 16 cells. Over 20 people at a time were arrested during individual terrorism investigations in both 2005 and 2006 and some had to be sent to Belgravia police station, which is not set up to deal with terrorism suspects. In addition, the normal day-to-day work of Paddington Green police station, which serves the local neighbourhood, was severely disrupted.

* there are no dedicated facilities for forensic examination of suspects on arrival. Cells have to be to specially prepared for this purpose, which is time consuming and further exacerbates the lack of accommodation.

* there is no dedicated space for exercise. Part of the car park can be cleared to provide a small exercise yard but this takes time to arrange and the car park is overlooked. This is likely to reduce considerably opportunities for exercise.[48]

* only one room is provided for suspects to discuss their cases in confidence with a solicitor.

* there are no facilities on site for the forensic examination of equipment such as computer hard drives.

* the videoconferencing room is too small to accommodate judicial hearings on the extension of the period of detention. Such hearings are usually now held in the entrance lobby, which is itself cramped, is a thoroughfare into the custody suite, and opens into the staff toilets at the back. It is clearly an inappropriate location for such a crucial part of the detention process.

(Source)

And so it was, shortly after the completed £490,000 refurbishment of Paddington Green Police Station, Moore photographed to the smell of fresh paint.

[Keep reading below]

CCTV camera with courtesy screening over toilet, holding cell D

Holding cell D.

28 Days is a continuation of Moore’s preoccupation with sites of state apparatus, but this was not always his interest. During the nineties, Moore worked in New York as a commercial photographer, Upon his return to his Britain, he spent three years piecing together The Velvet Arena (1994), a look at the textures, couture and gestures of high society, openings and schmoozing … canapes and all.

From here Moore, still concerned with the dark weight of the familiar made photographs of the House of Commons. He describes The Commons (2004) as a forensic view. “British people know what the House of Commons looks like,” said Moore via Skype interview. His response was to get close and change the view; he focused on corners, carpets, perched flies, scratches in the wood and banisters.

The Commons was pivotal in Moore’s development. He argues that photography has always been entangled in politics, specifically the British Empire. Following the destruction by fire of the existing Houses of Parliament on 16 October 1834, Barry and Pugin designed the new houses for British law with Gothic-Revivalist importance. They were completed in 1847. Photography’s earliest manifestation came about in 1839 with the daguerreotype.

Law, reason, progress, conquest, taxonomy and technology drove the British Empire through the end of the 19th century. Photography, with its will to objectivity, played its part in stifling cultural relativism; it disciplined both colonialist and colonised. Against this history, The Commons, for Moore, was “born of political frustration.”

“It was important for me to break it down. I am probably most influenced by Malcolm McLaren than anyone else,” says Moore.

[Keep reading below]

Solicitors’ consultation room

Virtual courtroom.

“My volition as a photographer goes back to the want to use it as a democratic tool. Looking at state apparatus and panoptic sites, I see my work as an act of visual democracy. Any small chip I can make.”

In 2008, Moore made quite a large chip. For The Last Things, he negotiated access to the Ministry of Defence’s crisis command centre deep beneath the streets of Whitehall, London. Moore got the pictures no other photographer ever had, or ever will. Read my article for Wired.com about Moore’s experience working in the subterranean complex that – to this day – officially “does not exist.”

The Last Things more than any other portfolio, opened the door for Moore to work at Paddington Green. It was a body of work with which he could show he could be trusted. Besides the Police Station was vacant. “It was relatively low security,” explains Moore.

“Paddington Green was very different to the MoD crisis command center. Paddington Green is imbued with a history and a trajectory of history. I know about [IRA] terrorism and about interview techniques and who’d been held in there over the years.”

For Moore, 28 Days is a contrast of the old and the new. An old building with new fixtures. Old procedures replaced by new codes of conduct. “There were definitely some opinions from older police officers: ‘These are terrorists, what does it matter if a cell is painted or not?’ and there was a mix of young and old police officers. The architecture reflected the changing Metropolitan police,” says Moore.

Moore’s work at Paddington Green is a glimpse of an institution in transition; in a moment and not in use. It could be said the stakes were low for London’s Metropolitan Police; that the risk was minimal. It is likely Paddington Green Police Station will cease to operate as the first stop for terrorist suspects. Plans are afoot for a new purpose-built facility. For the authorities, Moore’s work is transparency, for us it is curiosity sated, and for the photographer it is a small victory for “visual democracy”.

Exercise area.

All Images Courtesy of David Moore

The daily game of pétanque, de Liancourt Detention Centre, France 2001. © Nicole Crémon

Nicole Crémon’s decade-old L’âge en Peine/The Age of Pain peers jejunely at a French prison used to lock-up old men. Even so, I just wanted to share this image. What the photograph lacks in composition it makes up for with its baffling scene.

The most secure game of bowls since yesterday’s game.

Geriatric Issues Previously on Prison Photography

Last November, I delivered a lecture entitled Photography and Haiti’s Prisons in the Aftermath of the Earthquake. (Listen here, prep here.)

The lecture was more about how scant photographic evidence compounded the scare-mongering in written media following the escape of over 4,000 prisoners from Haiti’s National Penitentiary, Port-au-Prince.

I also paid tribute to The New York Times for their tenacious investigation of a prison massacre cover-up at Les Cayes Prison, 100 miles west of Port-au-Prince.

I encouraged students to have both critical stances on these contested and emotional narratives, but also keep a look out for media follow ups to the situation in Haiti regarding prison conditions, the reconstruction of the justice/prison system, and policing in the capitol.

Today Bite Magazine! published a 10 image essay by Boots Levinson of the ongoing “round-up” of prisoners.

Prior to the earthquake, Haiti’s prisons were renowned for corruption. Levinson’s images show us policing activities but they do not answer whether these prisoners were guilty of a serious crime in the first place.

#PICBOD

So successful was Jonathan Worth’s Photography & Narrative (#PHONAR) course, that Coventry University has decided to repeat the open and free, web-based format once-more. Classes are already underway for the Picturing the Body (#PICBOD) course. I am pleased to say I shall be involved again. More on that later.

Visit the site #PICBOD website.

Each year, UNICEF Germany grants the “UNICEF Photo of the Year Award” to photo series that best depict the personality and living conditions of children across the globe.

Among the 2010 Honorable Mentions was Spanish freelancer Fernando Moleres for his documents of children in Central Prison, usually known as Pademba Road Prison, in Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown.

Click here, scroll down and click on his name to see the full UNICEF portfolio. Click here for Moleres’ full portfolio.

It’s often difficult to engage an audience with “new” images of prisons, but Moleres succeeded with the image of the collapsed official at his desk (above). The disorganisation of paperwork in this image works as metaphor for a broken institution – much as Hogarth’s littered furniture and bodies are metaphors for broken society.

It also works as a foil (for those who are familiar with) to Jan Banning’s Bureaucratics portfolio; even those of Banning’s subjects amid seeming disarray, never appear defeated like Moleres’ prison administrator.

“Pademba Road Prison was built for 300 prisoners, but it has more than 1,100 prisoners at present, many of whom are children,” explains Moleres.

Conditions are appalling and hearing trials is based more on chance than process. “Countless cases of unspeakable misery – that’s the life of those who are imprisoned here,” says Moleres. “There are no beds, mattresses or sanitary facilities. No electricity and no water. Hardly any food. Their relatives often don’t know anything about the fate of the prisoners.”

A broken, hectic institution.

Moleres continues with three examples, “Teenagers like 16-year-old Lebbise*, sentenced without trial to three years in prison because he allegedly stole 100,000 Leones (25 Euros). 17-year-old Hilmani*, sentenced without trial because he allegedly stole his uncle’s scooter. 17-year-old Manyu*, sentenced without trial to three years in prison because he allegedly stole two sheep. He died in prison in spring 2010.”

*Names changed

As an audience to this type of imagery, we should note that, in 2006, Lynsey Addario photographed in Pademba Road Prison as well as jails in Uganda. On the evidence of the photographs, conditions have not improved.

Moreles paints a picture of a wasteful, desperate and predatory environment in Pademba Road Prison. This is the common view of prisons in many African countries, and sadly the reality for children caught in these systems. Many of Moleres’ photographs repeat the scenes of prisons photographed by others working in Africa, eg, Nathalie Mohadjer (Burundi), Julie Remy (Guinea), Joao Silva (Malawi) and Tom Martin (Burundi).

The common threads of these portfolios is tension, filth, depleted light, malnutrition, overcrowding and the solitary gaze of a forlorn child.

Prisons are most destructive to young lives that are not prepared for induction to the unpredictable environment. I would say this of prisons in America and the UK just as readily.

UNICEF is right to shed light upon the most upsetting (and unseen) realities for the most disenfranchised children in our global society.

FERNANDO MOLERES

Moleres also won the Luis Valtuena International Humanitarian Photography Award for his story on the prison system in Sierra Leone.

Molores has photographed children and the issues that affect their since 1992. in over 30 countries. He has been recipient of a Mother Jones Grant, (1994), the “Juan Carlos King of Spain” International Prize (1995), an Erna and Victor Hasselblad Foundation Grant, Sweden (1996), a finalist for the Eugene Smith Prize (1997), World Press Photo award for “Children at work” daily life series (1998), W. Eugene Smith Prize, 2nd prize (1999), World Press Photo, Art category (2002), Revela International Award, Spain, (2009), Honorable Mention Philantropy Award (2010) and an Honorable mention for the Gijon international Prize.

http://www.fernandomoleres.com/

UNICEF PHOTO OF THE YEAR

The prizes for the UNICEF Photo of the Year, 2010 went to First: Ed Kashi; Second: Majid Saeedi; Third: GMB Akash.