You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Historical’ category.

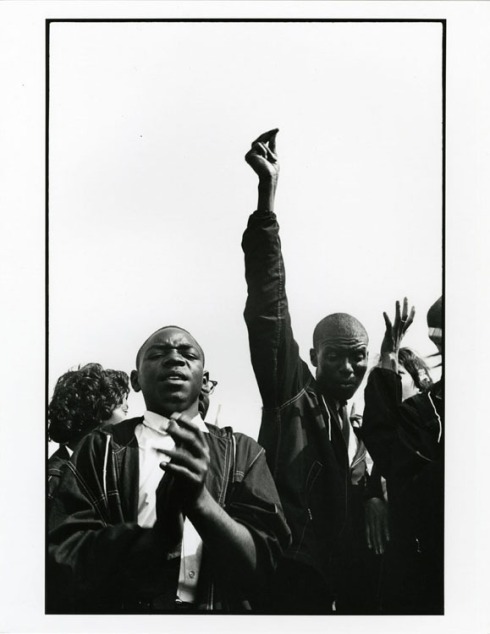

Photo: Bob Schutz. Inmates at Attica State Prison in Attica, N.Y., raise their hands in clenched fists in a show of unity, Sept. 1971, during the Attica uprising, which took the lives of 43 people.

Last week marked the 43rd anniversary of the historic Attica Rebellion. In conjunction with the anniversary, Critical Resistance New York City (CRNYC) has launched the Attica Interview Project, to support prison closure organizing in New York. CRNYC is looking for people with personal archives stories and will collect and facilitate oral history, video and audio recordings, and still images.

CRNYC’s documentation is grounded in a philosophy of self-representation.

“People who participate determine how and when they are photographed and recorded,” says a CRNYC statement. “We strive to represent interview participants not as victims, but as agents of social change struggling individually and collectively to improve their lives and conditions.”

ATTICA INTERVIEW PROJECT

Bryan Welton, a member with Critical Resistance New York City wrote:

At the time of the rebellion, the US prison population was less than 200,000. On the fourth day of the prisoner-led takeover of Attica, September 13th, 1971, then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller deployed New York State Troopers to set murderous siege on the prison. A campaign of sustained terror and repression to restore the power of guards and administrators at Attica followed. The systematic attack against the gains won by struggles inside and outside prison walls, which nourished the spirit of revolt in Attica and the broader prisoner movement of the period, parallels the rise of the prison industrial complex to where we stand today. Few people then imagined that the imprisoned population in the US would explode to 2.4 million.

The Attica Rebellion developed not only in response to conditions of dehumanizing racism and violence in the prison, but was strengthened by the confluence of imprisoned revolutionaries from Black liberation, Native and Puerto Rican anti-colonial, and anti-imperialist movements. The demands articulated by the Attica Liberation Faction unleashed an abolitionist imagination that continues to propel prisoner-led struggles up to today. Through oral history, the project seeks to document the legacy of repression, survival and resistance at Attica, while using material to shape a broader narrative about the PIC and abolition and fuel ongoing demands to close Attica.

Supported by sentencing reforms won through organized opposition to the Rockefeller Drug Laws and fights over deadly conditions in New York prisons and jails, prison populations in New York have decreased by 15,000 people since 2000. This decrease combined with the costs of maintaining staffing and infrastructure for empty prisons moved Governor Andrew Cuomo to close nine prisons in four years, with four more closures projected within the year. Although dispersed across the state and including both men’s and women’s prisons, what is common among these closure targets is their classification as minimum or medium security prisons holding people convicted of low-level drug offenses and “nonviolent crimes.” As we seize on any and all opportunities for prison closures, we understand the threat of cementing the “worst of the worst” classification for people held in maximum security, supermax and solitary confinement units and how the deepening of that logic enables the disappearance, dehumanization, torture and death of people in prisons everywhere. This criminalization is being amplified as prison-dependent economies, from the political representatives of prison towns to the 26,000 member guards’ unions (NYSCOPBA), desperately mobilize against decarceration and prison closures.

The stories of resistance, resilience, and struggle coming from the survivors of Attica and prisons across the country can offer not only a reminder of the history in which our movement is rooted, but a signal fire of which direction we should head. In the words of Attica Brother, LD Barkley, “The entire prison populace has set forth to change forever the ruthless brutalization and disregard for the lives of the prisoners here and throughout the United States. What has happened here is but the sound before the fury of those that are oppressed.”

CONTACT

To get involved contact:

Critical Resistance New York City

212.203.0512

PO Box 2282

New York NY 10163

Email: crnyc@criticalresistance.org

Photo: AP. Prisoners of Attica state prison, right, negotiate with state prisons Commissioner Russell Oswald, lower left, at the facility in Attica, N.Y., where prisoners had taken control of the maximum-security prison in rural western New York. Sept. 10, 1971.

THE NEED

Such a careful approach and revisiting of Attica’s history is timely and essential. An accurate version — and not the official state version — must be established. Following Attica, there were a number of inquiries (for example, Cornell Capa’s photographic survey of the facility here and here), however, not all inquiries met or served public need. Suspicions of a cover up of excessive violence and extrajudicial murder during the retaking of the prison have been constant.

The second and third parts of the Meyer Report (1975), an investigation of a commission headed by New York State Supreme Court JusticeBernard Meyer, were sealed and never released to the public.

The Democrat & Chronicle reports:

The focused on claims of a cover-up of crimes committed by police who seized control of the prison with a deadly fusillade of gunfire. Those allegations came from Assistant Attorney General Malcolm Bell, who had been part of an investigation into fatal shootings and other possible crimes committed during the retaking.

Wikipedia, quoted civil rights documentary Eyes On The Prize, triangulates the claims:

Elliot L.D. Barkley, was a strong force during the negotiations, speaking with great articulation to the inmates, the camera crews, and outsiders at home. Barkley was killed during the recapturing of the prison. Assemblyman Arthur Eve testified that Barkley was alive after the prisoners had surrendered and the state regained control; another inmate stated that the officers searched him out, yelling for Barkley, and shot him in the back.

It is believed parts two and three of the Meyer Report detail grand jury testimony given during an investigation into the riot and retaking. Late last year, a New York judge ruled the documents could be opened. It came at a request of Attorney General Eric Schneiderman. The majority of people are in support of the move, understandably given the length of time since the murders. The state troopers are opposed.

It’s high time the people had access to the same information the state has had for nearly four decades. Only then can we confirm or dismiss a state cover-up and the protection of law enforcement individuals and those from whom they took orders, namely then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

Photo: Goran Hugo Olsson. Source.

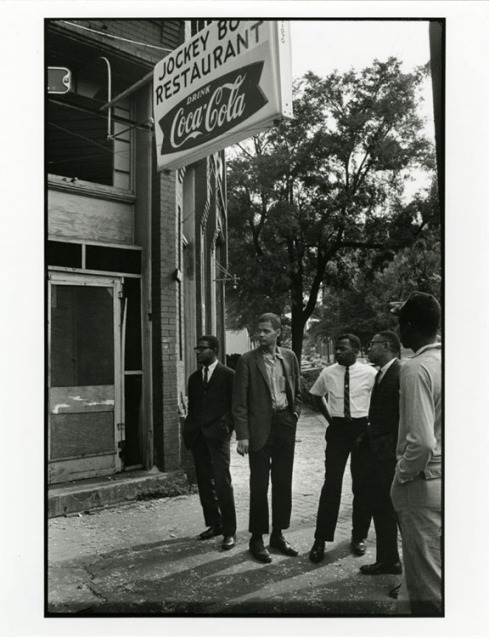

Bobby Seale, 11 Sept 1971. Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther movement, was brought in at one point during the rebellion to help with negotiations.

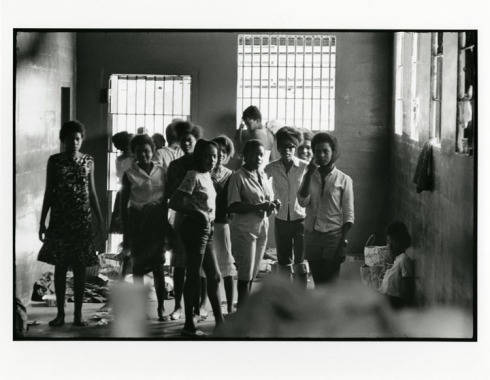

A prisoners’ make-shift hospital during the rebellion.

Source: Salon, Empire State disgrace: The dark, secret history of the Attica Prison tragedy

Law enforcement, civilians and press cover their nostrils from the airborne teargas following the state’s storming of Attica Prison, Sept. 13th, 1971.

Photo: John Shearer. Law enforcement escort a prisoner out of Attica following the storming of the facility. (Source)

This gruesome photo is one of several of murdered corpses included on this webpage. The images are uncredited, so I cannot verify there veracity. I’ve not seen them elsewhere. The boots, railings and sunken yard look consistent with Attica.

Prisoners are regimented following the state’s retaking of control of Attica Prison. (I have no idea when the trench was dug, by whom or for what purpose).

An injured prisoner is assisted out of D-Yard, following the state’s teargassing and assault upon the prisoners.

The aftermath.

Clean up.

RESOURCES

There’s so much out there online for you to dig into, so I humbly recommend these starting points:

Attica Uprising 101, is the best brief description of the events those 5 days in September 1971.

Forgotten Survivors of Attica, a group of guards and prisoners’ families alike who are in search of transparency and believe there was a state cover up.

Project Attica, a recent project with school children to teach them about racial politics, oral histories and Black America using Attica as a prism through which to do so.

Attica Rebellion Film Collection

Here is one of the better collection of images online in a single place.

Finally, I’d like to know if these photographs of prisoners’ corpses can be verified as being from Attica on the 13th, September, 1971. They are presented as images of those killed as a result of the state assault on the prison.

Today, the Philly Mag published a leaked document about the devastating decline in newspapers. It was created by Interstate General Media, owners of the Philadelphia Inquirer. It showed massive slumps nationwide but particular downturns in the fortunes of Philadelphia’s newspapers.

The slump has been rumbling on for over a decade now but the details in the leaked document make Will Steacy‘s project Deadline even more timely. Steacy is currently raising money to make a photobook and here’s why I think it deserves your support.

DEADLINE, by WILL STEACY

I was once Skyping with an artist on a residency in Europe. During the call, in the background, Will Steacy‘s head popped round the open door. Given the time difference, it was early morning for my friend, and for Steacy.

Pre-coffee, Steacy took the time to say hello. I noticed under Steacy’s arm a stack of the newspapers. Printed news from print newsrooms across the globe. Steacy told me it was his daily ritual to read, for hours, the news stories printed on actual paper. It shouldn’t have seemed so surprising, but in this era of digital information Steacy’s insistence on printed news was, in my mind, unusual. And comforting.

It makes sense that Steacy would not only notice — but also feel attachment — to the dying news daily in his once-hometown of Philadelphia. His photographs document an atrophying Philadelphia Inquirer newsroom. The number of staffers decrease, the presses go silent, the buzz of a breaking news scoop vibrates a little less.

The series is called Deadline, and Steacy is currently crowdfunding on Kickstarter to create a photobook version.

I tweeted last week that Steacy was “photographer, labor guy and workaholic” and deserving of your support. He’s worked on the series for 5 years. His father was an editor with the Philadelphia Inquirer for over 20 years before he was laid off in a round of cutbacks in 2011, and his family has been in the news industry for generations. Steacy talks of the newspaper as a form and as a bastion of an institution holding politicians, corporations and the like accountable to society as a whole. Steacy also believes the decline of the newsroom is a labour issue and more than just profits should dictate the operations of free press outlets.

Under corporate ownership every Inquirer asset is on the table in the strategy to stay alive. Ask any local, and they’ll tell you the Philadelphia Inquirer ain’t what it used to be. The focus on local coverage to secure it’s regional readership hails a goodbye to the days when the Inquirer racked up Pulitzers for fun.

The Philadelphia Inquirer still lives but it’s downsized from 700 to 200 staff, sold and moved out of its iconic headquarters, The Inquirer Building. This move, as documented by Steacy, is arguably one of the best visuals we have to grasp the size of the changes occuring now in news publishing.

While Deadline is specific to the Inquirer, the story is all too common. Large papers such as the Rocky Mountain News have shuttered completely in recent years. This devastating shift in news publishing was reflected in Philly Inquirer’s Hard Years Are Microcosm of Newspapers’ Long Goodbye, an article by my Raw File WIRED colleague Jakob Schiller, last year.

Deadline combines great images, great research, local and national narratives and a personal connection. The Kickstarter rewards are imaginative too: newsroom pencils and pin badges, and a limited edition artwork printed on the same presses that rolled out the Inquirer for decades.

Get over to Kickstarter and fund it!

Kickstarter reward at the $25-level. Poster: “A MIRROR OF GREATNESS, BLURRED” (Edition of 50, hand numbered, signed by artist, 20″ x 24″)

© Leon Collin

EARLY 20TH CENTURY CRIMINAL EXILE

Some enchanting photographs among the collection of Dr. Léon Collin. The problem is that not all are benign and not all were intended to be enchanting. Some were meant to outrage. The photographs of Dr. Collin recently surfaced after decades in the dusty attic of the Collin family home in Saône-et-Loire, France.

The visual difference and the enjoyment allowed by this historical (detached?) collection reminds me of those well-loved Australian police mugshots portraits. Beautiful character studies from absolutely abject circumstances.

PHOTOS AGAINST ABUSE

Between 1906 and 1911, Dr. Léon Collin made thousands of glass plates and manuscripts depicting the life of prisoners — from their departure from (outpost island) Île de Ré to their imprisonment in French Guiana or New Caledonia penal colonies.

Most of his photographs he made during crossings of the ocean, but Collin also made certain to make pictures on land, in the penal colonies. He was outraged by the harsh living conditions and, once, anonymously submitted his photographs to Le Petit Journal Illustré to denounce and expose awful conditions.

What an inspiring early political use of imagery. Although, I doubt they had much change-making effect. The intent was there.

HOW DID THEY GET TO THIS SCREEN?

Collin’s grandson Philippe Collin discovered the boxes. The Musée Nicéphore Niépce de Châlon-sur-Saône digitize them. Philippe Collin sold the rights to the city of Saint-Laurent. In anticipation of an upcoming exhibition at the future Centre d’interprétation de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine (CIAP). So far, nearly 150 photographs of Guyana prison camps have been brought together for the CIAP show. CIAP is built on the site of a former transit camp. Today, they photos landed on l’Oeil de la Photographie which has a dozen examples and I couldn’t help myself.

Thanks to Hester for the tip.

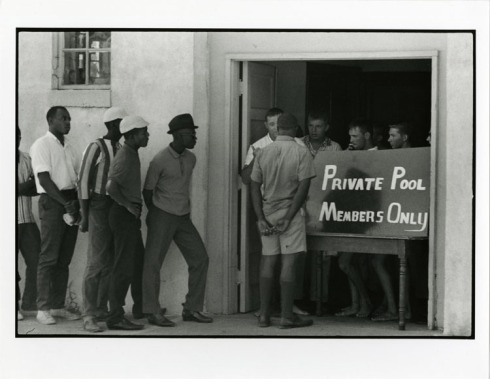

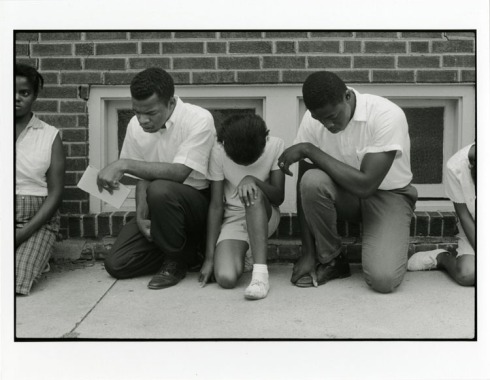

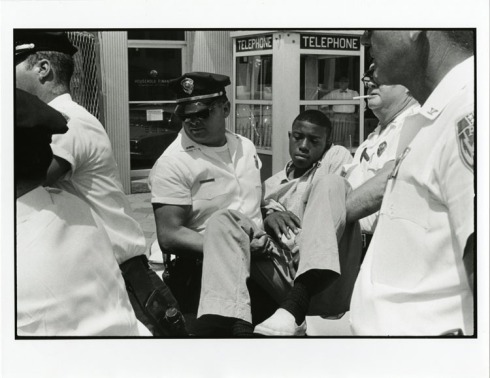

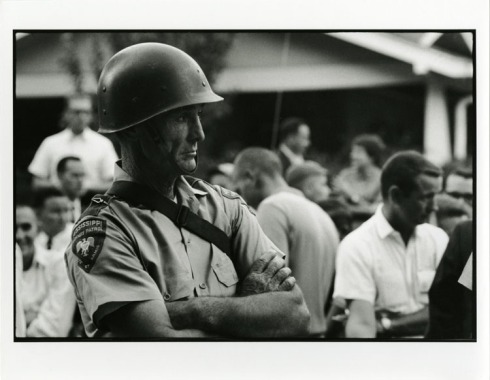

Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement

2014 is the 50th anniversary of the passage of The Civil Rights Act, the landmark legislation that prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

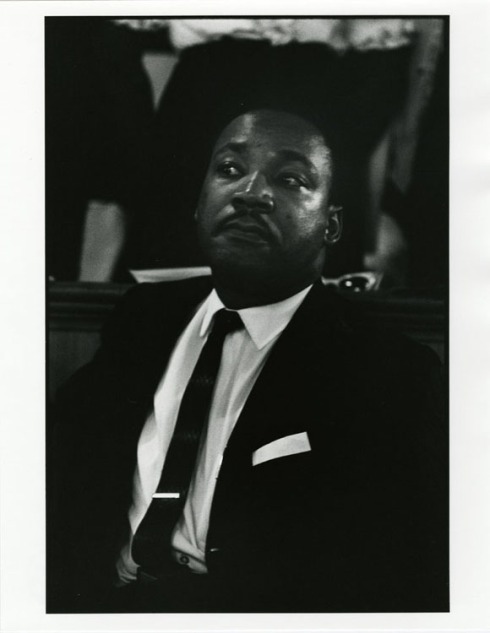

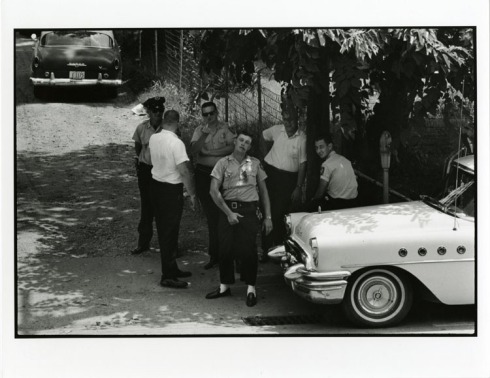

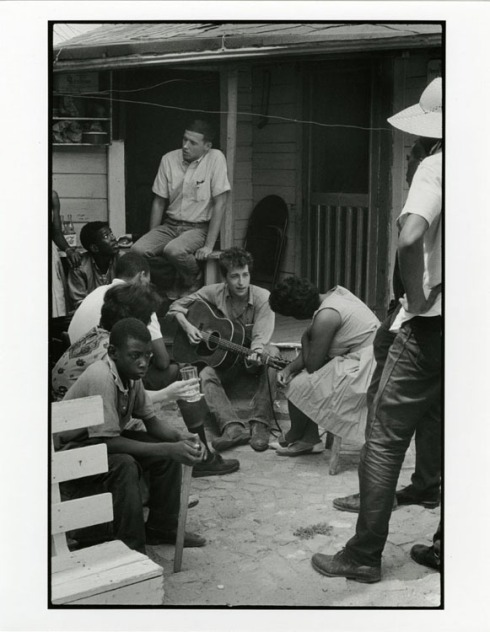

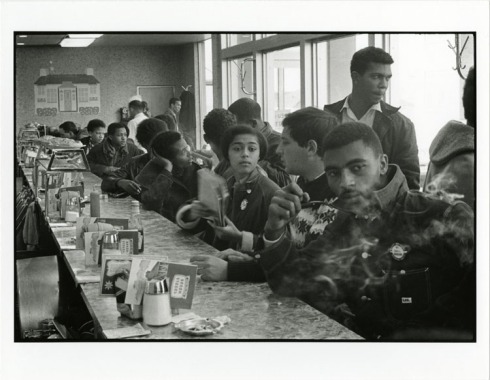

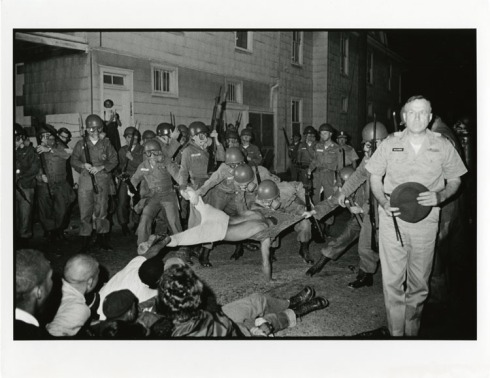

Danny Lyon was the first staff photographer — between 1962 and 1964 — for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Lyon would go on to make some of the most important bodies of work about the American condition (The Bikeriders; Conversations With The Dead) and as such his very early work as a very young man is often overlooked.

The Etherton Gallery’s exhibition ‘Danny Lyon: Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement’ opened on Saturday and shows 50 silver gelatin prints from Selma, Birmingham, and Montgomery, Alabama; Albany, Georgia; and Danville, Virginia. We see images of student protests and mobilization against racism, lunch counter sit-ins, student beatings, tear gassings, the jailing of Martin Luther King Jr., and the unscheduled visit of a young Bob Dylan to SNCC headquarters in Greenwood, Mississippi. Lyon, was harassed, beaten and jailed during his two years as a staff photographer.

SOME THOUGHTS ON AZ

Where better to look back on an era in which society treated people with different coloured skin than in modern day Arizona? The passing of SB1070 in 2010 was a legislative bill that essentially permitted veiled racism and racial profiling. In activism, folks are always on the look out for new allies and for audiences who really need to hear the message. A message of anti-racism message and some historical perspective is vital for residents of Arizona currently. I’m not saying that people of Arizona are inherently racist; I am saying the services and institutions that claim to serve them have procedures that result in racist acts.

There are some fine activists in Arizona (they’ve necessarily and wonderfully organised) and this is particularly true of Tucson and some clever geographer-activist-academics. May Lyon’s photographs play their part in making Arizonans and us angry. Lyon would want nothing more than his show to leave us rageful at our society of inequality.

DETAILS

Etherton Gallery, 135 S. 6th Ave, Tucson, AZ 85701 Tel: 520.624.7370. Email: info@ethertongallery.com.

‘Danny Lyon: Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement’ runs through March 15, 2014.

All photos: Danny Lyon © Dektol.wordpress.com. Courtesy of the Etherton Gallery

REST IN PEACE, PETE

Musician, folklorist and champion of the vernacular Pete Seeger died Monday. His legacy is formidable. The New York Times wrote:

His agenda paralleled the concerns of the American left: He sang for the labor movement in the 1940s and 1950s, for civil rights marches and anti-Vietnam War rallies in the 1960s, and for environmental and antiwar causes in the 1970s and beyond. “We Shall Overcome,” which Mr. Seeger adapted from old spirituals, became a civil rights anthem.

Part of Seeger’s widespread collection of folk songs took him, in March 1966, to the Ellis Unit of Huntsville Prison in Texas.

He traveled south with his wife and constant ally Toshi and their son Daniel. Bruce Jackson also joined them.

Afro-American Work Songs In a Texas Prison (30 mins.) documents the music African American prisoners used to survive the grueling work demanded of them. The prison work songs derive directly from those used by slaves and plantations and those directly from West African agricultural models.

Bruce Jackson wrote in his notes about the film:

“Black slaves used work songs in the plantations exactly as they had used them before they had been taken prisoner and sold to the white men. The difference was this: in Africa the songs were used to time body movements and to give poetic voice to things of interest because people wanted to do their work that way; in the plantations there was added a component of survival. If a man were singled out as working too slowly, he would often be brutally punished. The songs kept everyone together, so no one could be singled out as working more slowly than everyone else.”

Mechanization and integration of farming and forestry methods would soon lead to the disappearance of the work songs. There was an urgency to record them.

I spoke with Jackson in late 2011, when he said, “It is, to my knowledge, the only treatment (of that genre and era) that had ever been done. It was Pete’s idea and Pete paid for it.”

Seeger understood the contradiction. A significant type of folk music — a music that reflected the very survival of an oppressed group — was soon to be consigned to the history books, and yet that loss signified an improvement in their circumstances. As the film’s narration notes:

“The songs are still there but sometimes something is missing. The urgency is eased. Gone is that tension born of the original pain and irony of the situation that a man who could not sing and keep rhythm might die. The prison is the only place left in the country where the work songs survives. And it’s days are numbered. Another generation or two and its only source will be the archives. But given the conditions that produced the songs and maintained them for so long one can hardly regret their passing.”

Seeger understood people’s stories are wrapped up in their art. And with it their dignity. His curiosity was a rare and beautiful thing.

Watch: Afro-American Work Songs In a Texas Prison

A NOTE ON JACKSON

Bruce Jackson is a prolific prison photographer. Most of his work was made in the sixties and seventies in the South, from his Widelux images at Cummins Prison, his collected mugshots from Arkansas, his 1977 book Killing Time: Life in the Arkansas Penitentiary (Cornell) and his very recent 2013 book Inside The Wire (University of Texas Press) about Texas and Southern prison farms. Bruce Jackson’s book Wake Up Dead Man (University of Georgia Press) is a highly recommended study of work songs in Texas prisons.

From ‘Assisted Self-Portraits’ (2002-2005) by Anthony Luvera.

PHOTOGRAPHY’S NOT JUST DEPICTION!

There’s a fascinating discussion to be had at Aperture Gallery this Saturday December 7th. Collaboration – Revisiting the History of Photography curated by Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, and Susan Meiselas is an effort to draft the first ever timeline of collaborative photographic projects. Items on the timeline have been submitted either by members of the public or uncovered during research by Azoulay, Ewald, Meiselas and grad students from Brown University and RISD.

“The timeline includes close to 100 projects assembled in different clusters,” says the press release. “Each of these projects address a different aspect of collaboration: 1. the intimate “face to face” encounter between photographer and photographed person; 2. collaborations recognized over time; 3. collaboration as the production of alternative and common histories; 4. as a means of creating new potentialities in given political regimes of violence; 5. as a framework for collecting, preserving and studying existing images as a basis for establishing civil archives for unrecognized, endangered or oppressed communities; 6. as a vantage point to reflect on relations of co-laboring that are hidden, denied, compelled, imagined or fake.

Within the gallery space, Ewald and co. will discuss the projects and move images, quotes and archival documents belonging to the projects about the wall “as a large modular desktop.”

The day will create the first iteration of the timeline which will continue to be added to.

“In this project we seek to reconstruct the material, practical and political conditions of collaboration through photography — and of photography — through collaboration,” continues the press release. “We seek ways to foreground – and create – the tension between the collaborative process and the photographic product by reconstructing the participation of others, usually the more *silent* participants. We try to do this through the presentation of a large repertoire of types of collaborations, those which take place at the moment when a photograph is taken, or others that are understood as collaboration only later, when a photograph is reproduced and disseminated, juxtaposed to another, read by others, investigated, explored, preserved, and accumulated in an archive to create a new database.”

I applaud this revisioning of photo-practice; I only wish I was in NYC to join the discussion.

As you know, I celebrate photographers and activists who involve prisoners in the design and production of work. And I’m generally interested in photographers who have long-form discussions with their subjects … to the extent that they are no longer subjects but collaborators instead.

Photographic artists Mark Menjivar, Eliza Gregory, Gemma-Rose Turnbull and Mark Strandquist are just a few socially engaged practitioners/artists who are keen on making connections with people through image-making. They’ve also included me in their recent discussions about community engagement across the medium. I feel there’s a lot of thought currently going into finding practical responses to the old (and boring) dismissals of detached documentary photography, and into finding new methodologies for creating images.

At this point, this post is not much more than a “watch-this-space-post” so just to say, over the coming weeks, it will be interesting to see the first results from the lab. If you’re free Saturday, and in New York, this is a schedule you should pay attention to:

1:00-2:00 – Visit the open-lab + short presentations by Azoulay, Ewald and Meiselas.

2:00-2:45 – Discussion groups, one on each cluster with the participation of one of the research assistant.

2:45-4:00 – Groups’ presenting their thoughts on each grouping.

4:00-4:30 – Coffee!

4:30-6:00 – Open discussion.

6:00 – Reception.

If any of you make it down there and have the chance, please let me know what you think and thought of the day.