You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Historical’ category.

Jim Linderman just posted some original 1950s mugshots from Brooklyn, NY on Dull Tool Dim Bulb (one of my favourite photography blogs).

Of the images he says:

“Given attitudes, practices and institutional racism from 50 plus years ago, these sharp-dressers might have been just walking to work.”

Possibly, but we will probably never know the circumstances of their arrests.

I am fascinated by the tilted heads of many of the detained men and women. I read a hell of a lot of knowing defiance in the way many of the subjects gaze to the camera. It’s as if they are simultaneously acknowledging the photograph as a component in the apparatus of police power and the primary record of that unequal power. As such, they don’t hide or shrink but confront the photographic act.

All photos: Group of Original Mug Shot Photographs, New York City 1949 – 1955 Collection Jim Linderman

There were two categories of interviewees I planned to connect with during PPOTR – photographers and prison reformers. I didn’t expect to meet many individuals who satisfied both definitions. Ruth Morgan does.

Morgan became director of Community Works, a restorative justice arts program in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1994. Prior to that, she was director of the Jail Arts Program, in the San Francisco County Jail system (1980-1994).

It should be noted that the county jail system is entirely different to the state prison system and operate under separate jurisdictions. County jails hold shorter term inmates.

For three remarkable years, Morgan and her colleague Barbara Yaley had free reign of San Quentin State Prison to interview and photograph the men. In 1979, it was the sympathetic Warden George Sumner who provided Morgan and Yaley access. In 1981, a new Warden at San Quentin abruptly cut-off access.

“I think there were a few reasons [we were successful],” explains Morgan. “Despite the fact I was a young woman, I had a big 2-and-a-quarter camera and a tripod and so they took me seriously. That helped us get the portraits and the stories we did.”

The San Quentin News (Vol. I.II, Issue 11, June, 1982) reported on Morgan and Yaley’s activities. The story Photo-Documentary Team Captures Essence of SQ can be read on page 3 of this PDF version of the newspaper.

Ruth and I talk about how the demographics of prison populations remain the same; her original attraction to the topic; the use of her photographs in the important Toussaint v. McCarthy case (1984) brought by the Prison Law Office against poor conditions in segregation cells of four Northern California prisons; why she never published the photos of men on San Quentin’s Death Row; and the emergence, funding for, and power of restorative justice.

LISTEN TO THE DISCUSSION WITH RUTH MORGAN ON THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE

In 1972, Joshua Freiwald was commissioned by San Francisco architecture firm Kaplan & McLaughlin to photograph the spaces within Clinton Correctional Facility in the town of Dannemora, NY.

In the wake of the Attica uprising in September of 1971, the New York Department of Corrections commissioned Kaplan & McLaughlin to asses the prison’s design as it related to the safety of the prison, staff and inmates. The NYDoC wanted to avoid another rebellion.

The most astounding sight within Dannemora was the terrace of “courts” sandwiched between the exterior wall and the prison yard. It is thought the courts began as garden plots in the late twenties or early thirties, although there is no official mention of their existence until the 1950s.

Simply, the most remarkable example of a prisoner-made environment I have ever come across.

The courts were the focus of Ron Roizen’s 55 page report to the NYDoC on the situation at Clinton Correctional Facility. Sociologist Roizen, also hired by Kaplan & McLaughlin, conducted interviews with inmates over a period of five days:

“Inmates waited months, sometimes even years, to gain this privilege. The groups would gather during yard time to shoot the breeze, cook, eat, smoke, and generally ‘get away from’ the rigors and boredom of prison life.”

In the same five days, Freiwald took hundreds of photographs at Dannemora. Eight of those negatives were scanned earlier this month and are published online here for the first time.

“Since I’d taken these photographs, I’ve come to realize that these are something quite extraordinary in my own medium, and represent for me a moment in time when I did something important. I can’t say for sure why they’re important, or how they’re important, but I know they’re important,” says Freiwald.

Freiwald and I discuss the social self-organisation of the inmates around the courts, his experiences photographing, the air “thick” with tension and surveillance, the spectre of evil, and how structures like the courts simply do not exist in modern prisons.

LISTEN TO OUR DISCUSSION ON THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE

All images © Joshua Freiwald

All images © Joshua Freiwald

Poster created by the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) advocating support of prison rebellions, and the abolishment of alleged racist prison terror. Source: Wisconsin Historical Society

The most famous prison rebellion in American history began in the early hours of September 9th, 1971.

I’ve written about the Attica Prison Uprising before, mainly in relation to Cornell Capa’s involvement in the general politics of prisons and his testimony during the inquiry that followed the riot.

I wanted to share an image of this poster and ask you if you can imagine this type of visual being used today. It wouldn’t happen. Universities are less and less incubators for radical action; prison issues are rarely incorporated into overarching critiques of capitalism; and, sad to say, solidarity and Socialist motifs are derided in today’s media culture of garish graphics, breasts, comments of misdirection and ridiculous 24-hr coverage.

Not wanting to end on a down note, these groups are working against our society of excessive, blaring infotainment. Check them out.

Forest, St. Helena Island, South Carolina, 2010

Dana Mueller ‘s series The Devil’s Den are studies of former prisoner-of-war camps in which German POWs were put to work by the US military. At the end of WWII, there were over 400,000 prisoners who worked on local farms and in small industries.

From Mueller’s project statement:

“There is an irony where these German soldiers, both high-ranking Nazi officers and foot soldiers, were tilling the fields, cutting the lumber, picking apples, taking care of the American soil. This caring, benign work with the land stands in complete contrast to the horrific actions by Nazis and German soldiers in Eastern Europe of that time, such as Hitler’s scorched earth policy. […] Romanticism has played a role in understanding the relationship of Germans to the landscape. In some photographs the land is overgrown appearing in a kind of primal state, suggesting the return to the original forest. It also suggests a Fascist aesthetic of purity promoted by pre-war German culture. Innocence and purity can be seen as a natural desire to regress after one has become corrupted.”

I was fascinated by this little known chapter of U.S. history. Dana answered a few of my questions.

How did you arrive at this subject?

History, politics, memory and our understanding of individual experiences verses collective memory of past events, especially war, always interested me. As East German, my ‘German’ identity was shaped by the two wars. I talked at length with Art Space Talk about my personal responses.

As much as this is a personal investigation I want there also, ideally, to be a collective engagement with places of our past. With passage of time comes nostalgia and romanticism, which is a very complex way of relating, looking at the past.

Jeff N. Wall – for Southern Photography – recently wrote about one photograph of mine; it was wonderful to know that someone would spend actual time discussing a photograph and as an American to relate it to his own American history.

Camp Edenton field, Northeastern Regional Airport, Edenton, North Carolina, 2009, Photograph by Dana Mueller and Bonnell Robinson.

Near Camp Camden, Kershaw County, South Carolina (branch camp under Fort Jackson, SC) 2010.

Site of Pickett’s Charge, Gettysburg, Adams County, Pennsylvania, 2009. In 1944 tents for a German prisoner-of-war camp were erected on the field of Pickett’s Charge.

How do you think of landscape?

There is power at just looking at a landscape knowing that an event took place at one time, it is not what we see that sparks our fascination with the past, it is what remains invisible.

Photography is often about witnessing and revealing, but not here. In The Devil’s Den I suggest and contemplate; in relation to the experiences the soldiers had, the American guards had and the civil population who had them work on their farms, married their girls, etc.; in relation to the landscape and German identity – both the mythical and very real ties to the land, the homeland which define one’s nationality, and the irony that German soldiers found themselves here.

I am interested in crossing historical planes, i.e. the site of Pickett’s Charge is not only relevant to my ideas but also to American [Civil War] history, and those two come together; both relate to war, participation, consequences and follies.

What are your influences?

Romanticism in literature: all W.G Sebald’s works, especially Rings of Saturn, Emigrants and On the Natural History of Destruction, Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory, and many others that not necessarily discuss memory and landscape but have Eastern European backgrounds, i.e. Brodsky, Eva Hoffman, Milan Kundera, Czeslav Milosz. Also, the visual works of Anselm Kiefer and Casper David Friedrich.

How were the prisoners originally captured?

The North African Campaign by the allies began in 1940, between the Brits and the Italians. The Germans moved in in 1941. The U.S. got involved in late 1941 and militarily in 1942. Shortly after, the US Army created a prisoner-of-war camps all over the U.S. for captured German soldiers, many of whom were from Rommel’s African Tank Corps.

Others were captured at sea as German U-Boats neared the east coast, but there were not that many, and it happened sporadically. Many Germans were shipped from interim camps for German POWs in Normandy, France.

PPC factory near Camp Camden, Kershaw County, South Carolina, 2010. German prisoners-of-war worked at PPC factory between 1942 and 1946.

Camp Lee at Fort Lee Military Base near Petersburg, Virginia, 2009.

Camp Edenton, Northeastern Regional Airport, Edenton, North Carolina, 2009. North Carolina received its first group of POWs when German sailors were rescued from U-boat 352 that sank off the coast on May 9, 1942. The War Department eventually set up seventeen base and branch camps of Fort Bragg including Camp Edenton.

What happened to the prisoners?

Most prisoners were sent back to Germany after the war ended or a year later. The camps were in general also seen as rehabilitation facilities, where the American government wanted to re-educate the Germans in terms of democratic societies. As I talked to some historians, they mentioned that the foot soldiers and those less tied to Hitler’s ideology were stationed in camps on the east coast, higher ranking Nazi officers were send down south or west (Texas for instance).

Within a camp if there were a mix of soldiers, those who had allegiance to Hitler and never wavered and those who were happy to get out of the war, tensions existed and fights broke out. Therefore, they separated them depending on how ‘re-habitable’ they were. Nazis would rally at times in the camps but it never got out of hand as guards prevented revolts.

Most prisoners made friends with the Americans, they had their own newsletters, celebrated their holidays and some married American women. There were isolated escapes, most were caught soon after they fled. Most escapes were a result of the soldiers not wanting to return to Germany because Germany was completely devastated and life was better here, or Nazis knew they were not welcomed at home. Most prisoners had to return home unless, as I said, they married but those were very isolated instances.

Camps maintained strict guidelines and soldiers were treated well – times have changed when we look at Guantanamo Bay today.

Prisoners were used for labor, and some made even a little money so they could buy cigarettes and such. Off-and-on, some former German POWs come back to visit the camps and celebrate anniversaries even today. It’s strange to imagine that anyone would want to come back to where they were imprisoned. Not all was rosy – there were tensions between American guards and the prisoners, but overall the soldiers contributed to lumbering, harvesting, laboring in factories, etc and were tolerated by most of the American public. Of course, there were many Americans who thought ‘Why spend money to keep these people here?’ but as long as the prisoners contributed in terms of labor the practice became more accepted.

Melon field, St. Helena Island, South Carolina, 2010

Tomato field, St. Helena Island, South Carolina 2010. German prisoners-of-war stationed in Beaufort, SC, lumbered forests, worked in the fields and on farms at St. Helena Island.

Gettysburg, Adams County, Pennsylvania, 2009.

Are these sites marked?

Not all of them are forgotten. Only some are marked and some are just known to be sites by locals or at the Historical Societies in towns. For example, the site of Pickett’s Charge which is imbued with American Civil War history was also, amazingly, the field where they decided to put up a German POW camp. I found a sketch of the camp in Gettysburg. In 1944, it was mostly just tents. Once winter arrived, they moved POWs to more solid structures, some existed on military bases already and others were built for them, such as Camp Pine Grove, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. The foundations of the camp’s facilities are still visible underneath the overgrowth.

Other areas where prisoners actually worked I found through coincidence as I traveled along and inquired, for instance Sheldon’s farm and cotton field was owned by an American family whose son I met by chance near Elizabeth City, NC and who told me that he remembered the prisoners working in the field. His parents treated them well and the soldiers seemed content.

Camp West Ashley (below) is only place I photographed that had a marker. The ruin, which consists of a chimney, was saved by the residential neighbors who petitioned to save the historical spot instead of having it torn down, moved and the small piece of land used for development.

Other places are still working military bases, such as Camp Peary in Virginia (below) which I had no access to because today it’s the location of a covert CIA training facility known as “The Farm.” and I needed to improvise and find other ways of photographing it.

The camp at Beaufort, SC (below) was very interesting as the camp was located where is now a recreational park and structures of the building were only recently demolished, which made local news. So in terms of finding things, I base my direction of where I go on facts from literature, see below, or I just go to areas that are known to have had prisoners and I talk to people who might know the local history and then they tell me stories, or I find references at the local library or Historical Society.

Camp West Ashley, Charleston County, South Carolina 2010. The remaining chimney marks one of five prisoner of war camps established in the Charleston area toward the end of World War II. The West Ashley camp existed for only two years and consisted mostly of tents.

Camp Peary across the York River, York County, Virginia, 2009.

Site of former German prisoner-of-war camp, Beaufort, South Carolina 2010. The camp was located at Pigeon Point Park where barracks of the camp were recently demolished.

And finally, what resources exist for readers who want to know more about his shrouded episode of American history?

In regards to contemporary American politics, Hendrik Hertzberg at the New Yorker wrote Prisoners, a very interesting article some months ago. As for books, I recommend:

Stark Decency: German Prisoners of War in a New England Village, Allen Koop

Nazi Prisoners of War in America, Arnold Krammer

Hitler’s Soldiers in the Sunshine State: German POWs in Florida (Florida History and Culture), Robert D. Billinger Jr.

Stalag Wisconsin: Inside WWII Prisoner of War Camps, Betty Cowley

We Were Each Other’s Prisoners: An Oral History Of World War II American And German Prisoners Of War, Lewis H. Carlson

Behind Barbed Wire: German Prisoner of War Camps in Minnesota, Anita Buck

Guests Behind the Barbed Wire, Ruth Beaumont Cook

The Barbed-Wire College, Ron Theodore Robin

Nazi POWs in the Tar Heel State, Robert D. Billinger Jr.

Local libraries and Historical Societies have references to communities that housed German POWs. Both will have actual news materials and old photographs available. I found these original photographs of German POWs and campsites in Pennsylvania, at the Adams County Historical Society, PA.

Copyright: Adams County Historical Society, Gettysburg, PA.

Copyright: Adams County Historical Society, Gettysburg, PA.

The Great Dismal Swamp, Virginia/ North Carolina border, 2009. © Dana Mueller

___________________________________________________________

*There’s some irony in the fact that one of the U.S. camps Mueller photographs is called Edenton. Eden? Paradise it was not. Likewise, in the UK, the most famous former POW camp is Eden Camp in Yorkshire, which is now a heritage museum.

If you don’t know about Documerica on Flickr yet, you should.

“For the Documerica Project (1971-1977), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) hired freelance photographers to capture images relating to environmental problems, EPA activities, and everyday life in the 1970s.”

I particularly appreciated the 100 photos by Michael Philip Mannheim which document noise pollution and structural damage within the community around Neptune Road in Boston.

We live in a time in which imagery of aeroplanes in close proximity to buildings wheedle at our unconscious; the pregnant threat of collision is always with us. Mannheim’s subjects on Neptune Road share a different type of agitation. They’ve seen an extra runway inserted, their neighbourhood split in two and a rail link nestled against their properties. The noise, vibrations and ever-presence of aircraft for these folk is menacing but for very different reasons.

Just wanted to share.

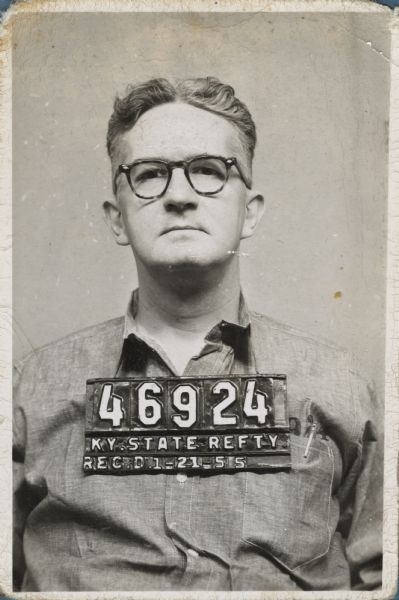

CARL BRADEN

I was surfing through the Wisconsin Historical Archives, like you do, and came across the above image of Carl Braden.

Braden and his wife Anne Braden were journalists-turned-activists who were part of the union movements and later the radical interracial left of the 40s and 50s. The Braden’s bought a house on behalf of the Wade family, their African American friends in suburban Louisville, Kentucky. When neighbours found out a Black family had moved in they burnt a cross outside the house and went after the Braden’s. Carl was charged with sedition in what is known as the Wade Case. Carl was sentenced to 15 years and served 8 months, eventually paying $40,000 to get out.

The Anne Braden Institute (ABI) now operates out of the University of Louisville. The ABI has a Flickr stream of scenes from her full life.

KARL BADEN

Karl Baden has chosen to put himself in the picture everyday for 24 years. Somewhere he has set up a self-imposed mugshot identification room. All these can be seen at his website Every Day.

It’s worth noting that Baden and Noah Kalina are the original and best for these vaguely masturbatory, mirrored versions of themselves in time-lapse. Others include a girl with a nice set of scarves, two dudes (one and two) with beard-growing missions, a guy with an 800 day commitment and Homer Simpson.

There is also Diego Goldberg who self-documents he and his family once a year, every year on the 17th June.

Baden has established a unique set of data for a limited case study in visual anthropology. The date runs like an I.D. number at the bottom of his shots.

As Baden describes the project, he removes emotion and variables from the photography, just as police or criminal justice photographers do for mugshots:

Every Day is performed within a set of guidelines. […] Reserved exclusively for this procedure are a single camera, tripod, strobe and white backdrop. […] I use the same type of high-resolution film (Kodak Technical Pan until it was discontinued in 2007, Ilford Pan F since then) and the same strobe lighting. The camera is always set and focused at the same distance. When taking the picture, I try to center myself in the frame, maintain a neutral expression and look straight into the lens.

Baden lists the key tenets of Every Day to be mortality; incremental change; obsession (its relation to both the psyche and art-making); and the difference between attempting to be perfect, and being human. I’ll grant him those things, but I also wonder is does the project not feel like a sentence?

And my question to you, readers, is what should we make of this type of project? It could be just inventive fun or it might be one of the most present-minded approaches to photography there is? I can’t decide.