You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Non-Prison’ category.

© Paolo Patrizi, from the series Migration

This week, I wrote two pieces for Wired on Google Street View. The first was a gallery of the various projects spawned by GSV, and the second was a piece about authorship and the repetition of nine scenes in two of the most well known GSV projects (Jon Rafman’s Nine Eyes and Michael Wolf’s A Series of Unfortunate Events and FY.)

Anecdotally, the photo-thinkers out there are converging on Doug Rickard’s A New American Picture as the most robust work. A close contender though is the relatively new No Man’s Land by Mishka Henner.

© Mishka Henner

No Man’s Land (more images here) is a disturbingly large selection of GSV screen-grabs of (presumably) prostitutes awaiting customers on the back roads of Italy. Henner says:

I came across communities using Street View to trade information on where to find sex workers. I thought that was the subject to work with. Much of my work is really about photography and this subject tapped into so many aspects of it; The fact the women’s faces are blurred by the software, that they look at the car with the same curiosity that we have when looking at them, and finally, that the liminal spaces they occupy are in the countryside or on the edge of our cities – it all has such great symbolism for our time. And that’s aside from the fact these women have occupied a central place in the history of documentary photography.

But for traditionalists, No Man’s Land is a long way from the spirit of documentary photography. Of Henner’s work and of all GSV series generally, the ever-outspoken Alan Chin says:

“Google Street Views is a navigational tool, an educational resource, and sure, it can reveal a lot about a place and a scene at a given moment in time. But if you, the artist, are really so interested, then go there and take some pictures yourself. This is about as interesting as cutting out adverts from magazines that have some connection and then presenting your edit as a work of art. Post-modern post-structuralist post-whatever denizens of of the art world and academia love this shit. Which is well and good for the university-press industry. But it has little to do with actual reporting and actual documentary work in the field.”

Well, just last week, I came across Paolo Patrizi documentary photographer that actually took himself to those byways.

For Migration, Patrizi has keenly researched where these women have come from and where, if anywhere, they may be going. From the project statement:

“The phenomenon of foreign women, who line the roadsides of Italy, has become a notorious fact of Italian life. These women work in sub-human conditions; they are sent out without any hope of regularizing their legal status and can be easily transferred into criminal networks. […] For nearly twenty years the women of Benin City, a town in the state of Edo in the south-central part of Nigeria, have been going to Italy to work in the sex trade and every year successful ones have been recruiting younger girls to follow them. […] Most migrant women, including those who end up in the sex industry, have made a clear decision to leave home and take their chances overseas. […] Working abroad is therefore often seen as the best strategy for escaping poverty. The success of many Italos, as these women are called, is evident in Edo. For many girls prostitution in Italy has become an entirely acceptable trade and the legend of their success makes the fight against sex traffickers all the more difficult.”

Patrizi is interviewed on the Dead Porcupine blog and talks about the unchanging situation, the pain experienced by the women, their reactions to him, and the destruction of woodland by authorities in attempts to literally expose the illicit encounters. It’s a must read.

The images in Migrations are inescapably bleak; therein lies their power.

© Paolo Patrizi

© Paolo Patrizi

© Paolo Patrizi

© Paolo Patrizi

Patrizi’s Migration induces a visceral shock; images of the littered make-shift sex-camps turn the stomach. When human fluids are dumped, it is not usual that humans continue to function in and around them. These workstead pits of dirt, tarps and abuse are shrines to the shortcomings of globalisation and the social safety net.

By contrast, Henner’s work allows us to keep a safe distance. He even saves us the trouble of finding these scenes on our own computer screens; we’re detached one step beyond. We are cheap consumers.

Patrizi’s photography with its clear evidence of his boots on the ground don’t allow us to share Henner and Google’s amoral and disinterested eye.

On Henner’s virtual tour, we cruise, at 50mph. We don’t stop, we don’t get out the car and we don’t get too close. We might as well be in another country … which of course we are. Patrizi’s work walks us by hand to the edge of the soiled mattresses and piles of discarded condoms.

Patrizi’s images counter the washed out colours, the flattening effect of wide-angle lenses, and the perpendicular viewpoint of GSV. Instead, they involve texture, depth, legitimate colour, details and different focal points along different sight-lines. In other words, Patrizi’s Migration engages the senses and the basics of human experience. Patrizi’s photographs return us to the shocking fact that that these women are human and not just bit-parts in the difficult social narratives of contemporary society. Works full of threat, fear, flesh and blood.

By comparison, Henner’s screen-grabs are anaemic.

Via del Ponte Pisano, Rome, Italy. © Mishka Henner

© Mishka Henner

Carretera de Ganda, Oliva, Spain. © Mishka Henner

© Mishka Henner

Founded in 2005 by by Emily Schiffer, a Magnum Foundation Emergency Fund grantee, My Viewpoint on South Dakota’s Cheyenne River Reservation, is a youth photography initiative “invested in young people’s inherent visual curiosity.” The images from Seeing is Fun are captivating.

The program has students (ages 6-20) apprentice with professional photographers, working in both analog and digital photography and printing their images in an onsite darkroom

My Viewpoint is run through the Sioux YMCA in Dupree, SD, and in partnership with Daylight Community Arts Foundation.

From the Daylight Magazine blog:

Shipping and Receiving: Photographs and Letters Between Venice, CA and Dupree, SD

August 6–September 30, 2011

Venice Arts Gallery in Venice, California

Opening Reception: Saturday, August 6, 5-8 p.m.

This exhibit features the photographs taken by students in the My Viewpoint photography program, and highlights a collaborative photographic exchange between the youth in the My Viewpoint program and youth at Venice Arts, conducted over 2010 and 2011.

Children of the Cheyenne River

July 23–September 4, 2011

Fovea Exhibitions in Beacon, New York

Opening Reception: Saturday, July 23, 5–7 p.m.

Artist Reception & Talk with Emily Schiffer: Second Saturday August 13, 5–9 p.m.

This exhibit is comprised of medium format black & white photographs of the students in the My Viewpoint photography program by the program’s founder Emily Schiffer, accompanied by a narrative text that explores Schiffer’s perspective on her evolving relationship with them, as well as photographs and text from the students.

Lorenzo Meloni‘s series Amal begins by quoting a 21 year-old Palestinian, “In my short life, I’ve seen nothing that makes me hope for peace; I’ve only seen destruction, death, pain. In my life, I’ve only seen the sea once.”

Amal contains a variety of styles and weaves the viewer through multiple emotions in a short space of time. It’s confusing … in a good way. That depth fits with the complex politics of the region.

Bruce Gilden’s street shooting methods polarise opinion. His “ambush tactics” (for want of a better phrase) are, for some, the exercise of any photographer’s right in public space, for others he just goes about stuff in a rude way.

Anyway, here’s a TMZ-style photo exclusive of Gilden in front of the camera and not behind it. Gilden the ambushed; not Gilden the ambusher.

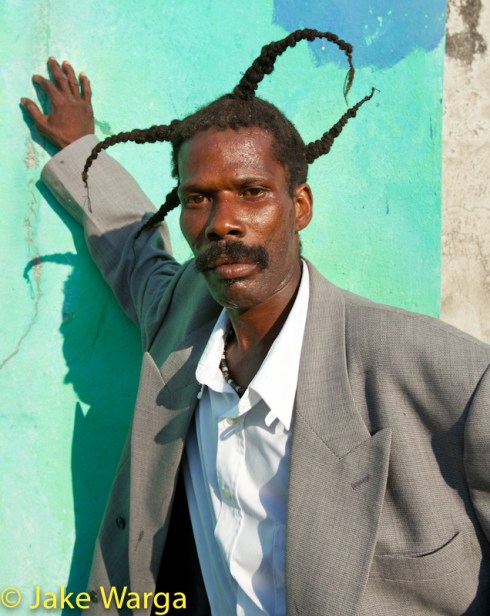

Journalist Jake Warga made these photographs in April. Warga was not part of Gilden’s entourage. We can presume that Gilden, at this time, was shooting Haiti: 15 Months Later.

I was critical of Gilden in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake suggesting his images were little more than a digitised freak-show.

Warga was not surprised the Haitian, who he described as “drunk out of his mind on cheap wine” was attracted to the documentary film crew following Gilden through the graveyard with their photo accoutrements.

“He wanted his photo taken,” says Warga, “I try not to be seduced by spectacle but it was the only way he’d leave me alone. In turn, he gravitated towards Gilden’s cameras, joining the circus of gazes already in Bruce’s orbit.”

The bizarre nature of this interaction can be put down to a mixture of grief, inebriation, intrusion, Gilden’s personal theatre, and the scene acted out by the Haitian man. And all this in a cemetery.

This is probably just another day at the office for Gilden who makes a habit of hanging out with violent persons.

Confusing layers here no doubt, but for me, the take away is Gilden’s flitting averted eyes (top image). As if part of some karmic return, this Haitian man getting up in Gilden’s grill can be read as a metaphor; as a spectre, and brief embodiment, of Gilden’s many victims down the years.

The tables are turned and it looks briefly unsettling doesn’t it?

Aired on BBC last month, Adam Curtis‘ All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace continues his knack of unnerving the viewer with hypnotising visuals and narratives that knits science, tech, neuropsychology to corporate and political ideologies. His use of music is also tragicomic.

Curtis is on top of his game. The BBC blog on his work and his own blog are good places to start, but this is the most user friendly place to get all his short-films documentaries.

All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace

All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace examines our collective hopes for the liberating experience of computer technology, networks and new modes of interaction.

Early network and internet engineers believed that our desires to free ourselves of government control, top-down authority and a globe modeled on the requirements of nation states, could be achieved by an embedded non-hierarchical network of communication.

Episode 2 focuses on ecosystems and how software developers have evoked myths of natural equilibrium to sell the idea that all forms of (computer-based) connectedness are inherently beneficial. I couldn’t help think of the persistent argument that “the internet is democratic”. It is not democratic, and yet the argument recurs time and time again – particularly as it applies to blogging and near-free publishing tools.

There are large corporate powers that dominate the internet; it’s no democracy. In terms of market penetration and information gathering – the multi-national tech companies dwarf the extraction and industrial manufacturing giants of the past. Through data they wield massive power. One power structure has been replaced by another.

Unfortunately, Curtis’ conclusion is that the unfulfilled promises of technology have led to cultural nihilism, in which we’ve convinced ourselves we are isolated machines and our only purpose it is to carry genetic data AND as such we’ve abandoned the idea of community. Bleak.

While you’re at it you should watch The Power of Nightmares: The Rise of the Politics of Fear. It is a wonderful and cogent explication of the shared history between fundamental Islamist thought and U.S. Neoconservatism.