You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Opinion’ category.

Inmates line up for work early in the morning at Estrella jail. © Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA

Yesterday, the Guardian ran a gallery of Jim Lo Scalzo‘s photographs of a female chain-gang in Maricopa County (Phoenix), Arizona.

To people who are unfamiliar with the chain-gangs, established by the controversial Sheriff Joe Arpaio (the self-titled “Toughest Sheriff in America”), Lo Scalzo’s images may be a shock. Certainly, they are fascinating.

Unfortunately, this is not an example of a photographer gaining exclusive access to an invisible institution. To the contrary, inmates of the Maricopa County Jails are arguably the most frequently photographed prisoners in the United States. Approach Lo Scalzo’s work with caution.

Jon Lowenstein photographed the female chain-gangs in March, 2012 and Scott Houston photographed the all-female chain-gang when it was first established almost a decade ago.* These are only three photographers of hundreds who have visited Tent City, Estrella Jail and followed chain gangs out on to the streets.

The Guardian writes in it’s brief introduction, “Many women volunteer for the duty, looking to break the monotony of jail life.” That might be true, but it is also the message peddled by the Sheriff’s office and it also stops short of asking why these women have been ushered into the jail system. I should say at this point, these are women on short sentences locked for non-serious, probably non-violent offenses, likely drug use, prostitution, petty theft. If I may generalise, they are a nuisance more than they are a danger. They are victims as much as they are victimisers.

What must to do with Lo Scalzo’s photographs – and with others like his – is appreciate how they were made; more specifically we must appreciate the pantomime that is put on display for the public and put on for the photographer.

I have spoken to many photographers who have described how Arpaio directs a “media circus.” I have written before about his press-staged march of immigrant detainees through the streets of Phoenix. He dresses citizens serving time and non-citizens awaiting immigration hearings in the same pink underwear and striped jumpsuits.

Let’s not deny that Sheriff Arpaio is on message, dominates message and understands visual symbols and the power of the image probably as well, if not better, as any of us who make, discuss and revel in photography.

There is certainly a lot more to be teased out about Arpaio’s near 20 years in office and his media savvy, but now I’d like to turn our attentions away from photography and towards a socially-engaged art project of admirable sincerity and complexity which might teach us more about Maricopa County than photographs alone.

Throughout 2011, Assistant Professor of Multimedia Gregory Sale at Arizona State University (ASU), carried forth It’s Not All Black & White a program of talks, installation and interventions at the ASU Art Museum.

It’s Not All Black & White intended to give “voice to the multiple constituents who are involved with the corrections, incarceration and the criminal justice systems.” To establish a discussion around the highly contested issues in a divided community, Sale and his team had to rely upon the trust and input of museum curators, university faculty, students, sheriff’s deputies, incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, family of the incarcerated and so on and so forth. It is quite remarkable that under the same banner, Sale was able to invite Angela Davis to talk and in another event invite Sheriff Arpaio to a discussion on aesthetics.

Round table discussion at ASU Museum. Joe Arpaio on the right.

Incarcerated men were brought onto university grounds to paint the stripes in the ASU museum, Skype dance workshops were done to connect incarcerated mothers and daughters; the museum space was repeatedly given over to engagement instead of objects.

At the fantastic Open Engagement Conference, I shared a panel with Gregory. He said that for so long Sheriff Arpaio had controlled how people think of stripes and think of criminality in their community.

Gregory said one thing that really stayed with me. He said that for a brief period while It’s Not All Black & White was in the museum and the programmes went on, he was able to wrestle that control away from Arpaio and open a discussion that focused not on the blacks and the whites, but on the grey areas. In those grey areas are hard decisions and hard emotions. But, also in those grey areas, are solutions to transgression in our society that might look to root causes and solutions that engender hope and spirit-building instead of humiliation and penalty.

When we look at Lo Scalzo, Lowenstein, Houston and the works of countless others from Maricopa County we need to bear in mind the stripes and the spectacle of the chain gang is deliberate. Are the photographs showing us only the black and white of the stripes or are the photographs introducing us to meditate on the grey areas? I suspect they do mostly the former.

*Lowenstein had photographed immigrant detainees in Maricopa County’s ‘Tent City’ a few years ago. I included both Lowenstein and Houston’s work in Cruel and Unusual.

This is a super quick post and a bit of an image dump (I’ve been asked for installation shots.)

We are half way through Photoville and my thoughts are not coalesced yet. Of the event so far, highlights have been Josh Lehrer’s Becoming Visible: portraits of homeless, transgendered teens; Sim Chi Yin’s Rat Tribe for which he transformed the container to mimic a basement Beijing dwelling; and Russell Frederick’s Dying Breed: Photos of Bedford Stuyvesant.

More to find and more to percolate.

As I reported last week, we got off to a slow start. Customs and FedEx conspired to give us all anxiety-disorders by only releasing the artwork at 8am Friday morning. Huge playdits to organisers Sam and Laura for hounding FedEx while I sailed through Wednesday and Thursday with a C’est la vie attitude. Customs never said what the problem was but we presume it was Jane Lindsay’s bottle caps filled with resin.

We had 6 hours for install and it ended up taking 8; I was still sweating about and showing off my chest-wig as the public moseyed through that first (Friday) evening.

Further thanks have to go to Wally, Trevor and Lee for hanging the work of the 11 named photographers across one and a half containers – Alyse Emdur, Amy Elkins, Araminta de Clermont, Brenda Ann Kenneally, Christiane Feser, Jane Lindsay, Natalie Mohadjer, Deborah Luster, Lizzie Sadin, Yana Payusova and Lori Waselchuk.

I took care of the other half a container; the PPOTR wall. I scrawled quotes and stats freely on the corrugated surface. Whenever I had downtime last weekend, I’d return to the container and scribble some more.

The PPOTR wall contains images by 17 photographers – Jenn Ackerman, Jeff Barnett-Winsby, Steve Davis, Lloyd Degrane, Harvey Finkle, Tim Gruber, Scott Houston, Sean Kernan, Jon Lowenstein, Ara Oshagan, Joseph Rodriguez, Richard Ross, Adam Shemper, Marilyn Suriani, Stephen Tourlentes, and Sye Williams.

I’d like to Thank Deborah Luster, Yana Payusova and Lori Waslechuk for joining me for Saturday’s panel discussion. They were happy to share stories from their experiences shooting in Russian and Louisianan prisons and they parried my challenge as regards the utility of this type of photography with varied and solid positions.

Left to right: Deborah Luster, Yana Payusova, Lori Waslechuk, me. Credit: Graham MacIndoe

Did I mention the massive thunderstorms on Friday afternoon with forks of light cracking down on the skyscrapers of Manhattan? It was great. Then there was the party that was on, wasn’t on, on again. I went for felafel, came back, had a cheeky wine. Hung out with Bryan Formhals and Michael Shaw.

On Saturday evening, Susan Meiselas raised a glass to the Magnum Emergency Fund fellows. Wyatt Gallery was there, as were Amy, Yukiko, Lauren from the Open Society Institute’s Documentary Photography Project. I saw Peter Van Agtmael later and I’m banking on him for better installation shots. Also had the opportunity to finally talk to Chandra McCormick. I had tried to speak with Chandra during PPOTR. She and her partner Keith Calhoun photographed in Angola Prison before it became common to do so.

Photoville is a relaxed place to bump into people you want to bump into. The general vibe is that it is accessible, fun, pedestrian and at the same time maintains a high standard of work. Photoville is off to a good, solid, smile-making start.

I suppose the only other news is that I delayed my return flight so I remain here in NYC. The arrangements I made for deinstall fell through, so I’ve decided to take care of it myself.

In the meantime, I’m sprinting (or biking) around the city hobnobbing with people, making interviews and panicking about how journo-blogger disclosures should be written in an age of small and borderline incestuous photo-maker-media-networks.

I’ll add to that worry of over-familiarity more at the PDN The Curator Remix party this evening.

Tomorrow, very much looking forward to Lorie Novak’s panel discussion “Community Collaborations” as I’m wrestling with ideas and best practices for potential photography workshops in prison. I also plan to be at the Daylight Photographs Not Taken panel discussion.

Enjoy the pics.

Jane Lindsay’s bottle caps. (That’s Lou Reed’s NYPH pedestal).

Deborah Luster’s One Big Self

Lori Waselchuk’s Grace Before Dying

Yana Payusova’s Prisons

Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes

Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes

Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes

Brenda Ann Kenneally’s Andy and Tata

Amy Elkins

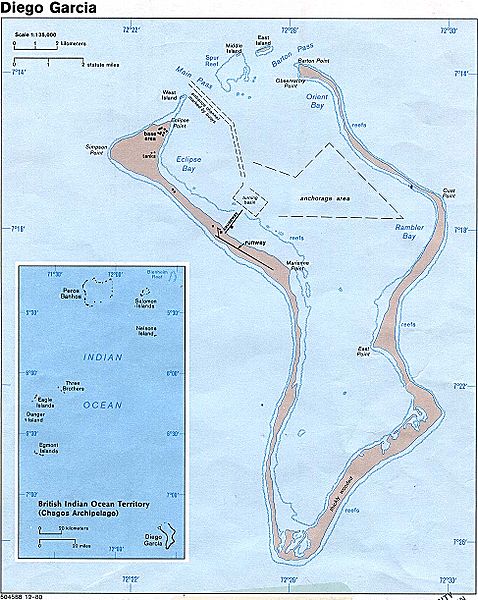

Diego Garcia Island, Indian Ocean, United Kingdom Territory. Rendition Flights Refuelled on the Island in 2002.

Two years ago, I used the above map to illustrate a piece about extraordinary rendition. Located between the east coast of Africa and the West coast of India, Diego Garcia is the largest of the Chagos Islands and until the 1960s had a permanent native population going back generations.

The United States wanted a Pacific military base and they British wanted the friendship. The Chagosians people were obstacles to the UK and US plans.

Stealing A Nation by John Pilger lays out in devastating simplicity how two of the mightiest powers lied their way into their own legal machinations in order to cheat over 2,000 people. The Chagosians were forcibly removed and those that haven’t died “of sadness” continue to live in squalor in Mauritius.

I challenge you not to be angry.

As many of you will be aware, Noorderlicht Photo Gallery and Photo Festival are threatened with closure if the Dutch government decides to go ahead with advice – by the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture – to cut €500,000 in funding. That amount represents 50% of Noorderlicht’s annual budget.

As many of you will also be aware, I have been a public champion of Noorderlicht. Last month I described my delight with working with the professionals at Noorderlicht; the post covers all the reasons I believe Noorderlicht is unique, principled and vitally important to the documentary tradition, as well as to all discourses within photography.

I won’t repeat myself here then in this post. Instead, I’d like to look at some of the language used by both the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture (or the The Cultural Council of The Netherlands, as it is alternatively known) and Noorderlicht.

CONTEXT

Noorderlicht has operated since 1980. It’s history and growth is impressive. There can be no mistake, Noorderlicht is of international importance. This is a fact, I think, the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture has paid least attention to. The Dutch are known for their exception book design, but in Noorderlicht they have an international pioneer in the genre of socially engaged documentary.

Unfortunately, that is part of the problem. The Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture characterises Noorderlicht as having to heavy a focus on documentary work and not enough participation in “the art discourse, theoretical reflection and experimental development.”

Noorderlicht has publicly responded to the recommendations twice (one, two).

Up front and to the point, Noorderlicht quotes the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture, listing the most direct of criticisms:

‘The figures for fund raising and sponsoring give evidence of limited insight.’ ‘Disappointing income of their own.’ ‘Because of the complex character it draws only a small audience.’ ‘Conveyance of information by discourse appears to weigh more heavily than visual qualities.’ ‘The number of visitors was very low.’ ‘Concrete plans in the area of education and an outreach to a wider public are lacking.’ ‘There is a concern that the peripheral programming with debates and publications is being privileged at the expense of appealing presentations.’

Noorderlicht does this in order to respond square on:

“Noorderlicht reaches a wider public than institutions that did receive a positive recommendation, has remained critical and self-critical, has generated great enthusiasm and earned an international reputation that the whole of The Netherlands can be proud of. That must not be allowed to be lost.”

Noorderlicht’s overall rebuttal goes into details of how it has “met all criteria.”

Ton Broekhuis, Noorderlicht director, wrote in an open letter to Joop Daalmeijer, president of the Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture:

“I dare to say that the Cultural Council’s final verdict on Noorderlicht was made on the wrong grounds; by this I mean purely theoretical, and certainly in terms of the interpretation of our quantitative data. You advise some whose requests were accepted to generate larger audiences and work on their business model. Noorderlicht has already accomplished these things. And yes, that was at the expense of the elitist, hothouse art debate.”

The politics of funding must also be examined. Noorderlicht argue regional inequalities and bias are at play:

Of the thirteen Northern institutions that several years ago were still financed wholly or in part by national disbursements, only four remain. Certainly in Groningen, where for instance all dance and all visual art is being scrapped, the clear fell is complete. A region where 17% of the country’s population lives is being palmed off with a disproportionately small share in national subsidies. The Council has clearly chosen for the Randstad (the conglomerate of big cities in the west of the Netherlands) and for a number of big players. In itself, this is not surprising: when only 10% of all the advisors come from outside the Randstad, a certain Randstad myopia is built into the process.

Dutch National Advisory Board for Culture also criticised Noorderlicht for not collaborating enough across the Netherlands. Noorderlicht’s response:

Why should Noorderlicht, as an autonomous institution which has set itself the task of operating internationally from the North of The Netherlands, have to show how it works with other institutions in the country? Are institutions in the Randstad also asked how they work together with national institutions in the region? How often do Randstad institutions present their products in Groningen?

Noorderlicht concludes with its view on the recommendation to cease funding:

“[…] The council is making a clear first move in a debate that has become urgently necessary. For whom is art? What is the role of art in society? In any case, Noorderlicht has a less narrow view on this than the Council does.”

This is all very punchy stuff and part of what is now undeniably a noteworthy, frank and public debate.

HAVE YOUR SAY

Noorderlicht has asked supporters to record video messages of support Send the file to Noorderlicht and they’ll post it on the Noorderlicht Youtube page. You have a spare minute?

Ed Kashi, on Noorderlicht Photo Gallery and Photo Festival: “National Jewel […] It is unthinkable to think that Noorderlicht would disappear.”

Other ways to support.

SEE ALSO

– Joerg Colberg’s Open letter in support of Noorderlicht: “Noorderlicht [has been] an important member of the photographic community for many years, a community that extends beyond regional or national borders.”

– Noorderlicht Photofestival faces closure, British Journal of Photography, 22 May 2012.

As you may know, I’ve recently relocated to Portland, Oregon. The Portlandia TV comedy narrative would have you believe this is a town full of loveable counter-culture stereotypes; under-employed dreamers, kombucha-swilling hippies, and coffee-obsessed yoga-rock-climbers, to name a few.

But …

PORTLAND IS NOT PORTLANDIA

It is fair to say that on the West Coast, the tech boom of the nineties – centred on Seattle, San Francisco and Silicon Valley – bypassed Portland. And the joke is that people pursued fire-eating, tattoos and weed instead of HTML and Java-code.

But Portland is not a harmless bubble populated only by self-aware, contented contrarians. Portland has the same problems with failing schools, violence and inequality as many large U.S. cities. Furthermore, the State of Oregon as a whole has seen dwindling public funds for education as measured against its burgeoning law enforcement and corrections budgets.

As a reality check, I’d like to recommend two articles.

Firstly, Our preoccupation with incarceration costs us in education, by Naivasha Dean in Street Roots:

Oregon is one of only a handful of states in the nation that spends more money on prisons than on higher education, a statistic that is often met with dropped jaws by students struggling for financial aid. The Department of Corrections has been one of the fastest growing state agency budgets that is eating up an ever-increasing percentage of the state’s General Fund. This does not bode well for Oregon’s future and represents a deeply misplaced set of priorities and an archaic approach to addressing crime and public safety.

Why is Oregon’s prison spending so out of control? Oregon can trace the trend directly back to 1994, when voters approved Ballot Measure 11. Measure 11 established mandatory minimum sentences for approximately 20 “person-to-person” crimes, and it automatically sends youth charged with any of those crimes, aged 15 and over, directly to adult court. Mandatory minimums are a one-size-fits-all approach to criminal sentencing that prevent judges from using their discretion and prevents Oregon from using smarter approaches to accountability and crime prevention.

Shortly after the passage of Measure 11, Oregon’s governor and legislature approved plans for more than 8,000 new prison beds, including siting for six new prisons. Since then, the legislature has authorized more than $1 billion for prison construction. As anticipated, Oregon’s prison population exploded — from 6,000 inmates in 1995 to more than 14,000 today, and the Department of Corrections budget more than tripled.

Secondly, Portland, the US capital of alternative cool, takes TV parody in good humor, by Paul Harris. This Guardian article, partly, dispels the temptation to get carried away with TV’s version of PDX life:

Portlandia is not the whole picture of life in Portland. Not everyone is white, urbane, child-free and in their 20s, or acting as if they are. In fact the city is 8% black and 9% Hispanic– communities that often live in poorer neighbourhoods that are gentrifying with newcomers who push out long-established families who can no longer afford rents.

Portland also has a problem with gang violence. […] One man who sees this side of Portland close-up is John Canda, founder of gang outreach group Connected. “I personally have been to 358 funerals,” he said of two decades working in the field. Connected, formed last year after a series of shootings, seeks to lessen violence by having volunteers walk the troubled streets, reaching out to Portland’s youth.

“Our message is talk with us. It starts with a greeting,” he said. For Canda, as a native black Portlander, the world of Portlandia and its concerns over recycling and organic food seem unreal. “It is like a parallel universe,” he said.

Graph courtesy of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Cruel and Unusual, an exhibition of prison photographs that I co-curated with Hester Keijser at the Noorderlicht Photo Gallery in Groningen, Netherlands closes on Sunday (8th).

You probably know about it because I haven’t been shy to promote it; it is one of my proudest achievements. I’d like to take this opportunity to share with you some thoughts on the Noorderlicht team and publish some installation shots. Part debrief, part abridged journal entries.

The show balanced two interrelated parts. One could not exist with out the other.

The main section of Cruel and Unusual looked exactly like a tradition photo show – ordered, framed prints of 11 named photographers. Cerebral and reliable. Mindful. The mind.

The counterpart was the PPOTR wall – a “mayhemic reflection” of some of the stories and images I encountered during Prison Photography on the Road. It included the photographs and quotes of another 18 photographers.

The PPOTR wall was messy, imperfect, unmediated, and attached to the core of my sprawling interest in prison imagery. It was the best solution Hester and I could think of to reflect our frantic immersion in international, blogging photo-territories. Physical, with tentacles, corporal. The body.

Body and the mind are inseparable. They communication with one another through a central nervous system. Noorderlicht, our host was backbone, nerve centre and sensitivity.

Outside of my home country (and my comfort zone) I clamped onto my host. Noorderlicht gallery connected mind and body; perfection with imperfection; polished ideas with raw, in-process threads; finished photographs with found stories.

The PPOTR wall was the first time I’ve tried to bring my sprawling project to some sort of overview suitable for visual consumption (lecture Powerpoint presentations excepted). As such, I was required to direct the PPOTR installation.

It is at the point of installation, one begins to appreciate the attitudes of the host and its staff.

As a practitioner with little experience in installation, the Noorderlicht installation team of Marco, Ype and Margriet were supportive without qualification, enthused, and willing to make gentle interventions when necessary. Their relaxed professionalism is one reflected through the organization from top to bottom. I worked with Charissa Caron on press liaison, with gallery director Olaf Veenstra on business decisions. Geert printed the work. There was always fresh coffee on hand. There were flowers in the gallery. At the opening they let dogs come in to see the artwork!

Noorderlicht is more than a workplace. It is a home.

It was somewhat of a risk for Noorderlicht to commission two photobloggers to curate. Yes, we have the knowledge and the online networks, but blogging (writing emails, forging prose, editing online galleries) is very different to herding photographers and liaising with gallery staff for a physical show.

I should say that Hester is a much more accomplished gad about phototown with a long CV of collaborations and in the past year has taken on the role of curator at large for the Empty Quarter Gallery, Dubai. Her knowledge and discipline propelled the pre-show nuts-and-bolts organizing. Without her, I’d have been knocked on my arse early in the venture.

There is a reason Noorderlicht took a risk on us though. It is because they do it often. Noorderlicht is probably best known for its international photography festival. The size and reputation of their festival is astounding given the foundation’s modest size. Take a look through the festival archives and see how many big name photographers showed their work at Noorderlicht before they became big names. They are pioneers.

Groningen is in the north of the Netherlands, 3 hours drive from Amsterdam and the rest of the cultural heart of Holland in the west and south (den Haag, Utrecht, Lieden and Rotterdam). Because of this Noorderlicht often gets overlooked or pigeonholed. I think in some cases, folk might be slow to acknowledge Noorderlicht’s accomplishments. We know how London and NYC dominate the cultural psyches of the UK and the U.S., and I think a similar imbalance persists in the Netherlands. If I am in anyway correct – and I wish I were not – then this is everybody’s loss.

The risk paid off.

Cruel and Unusual was extended by a week due to public demand. Visitor numbers have been substantial and the Dutch press went doolally over it. National radio, newspapers, magazine features – the whole shebang.

This does not surprise me. For many reasons, the subject matter is compelling. But I think the show has been a success because there is a dearth of discussion about prisons in Europe. As grand an ambition it may sound, Hester and I hoped the show would be a warning shot across the bows of Europe: DON’T REPEAT AMERICA’S MISTAKES. DON’T MASS INCARCERATE! It would seem people were hungry for Cruel and Unusual because the topic was a challenging breath of fresh air. Much of the work was also being shown in Europe for the first time. As thrilling as photography can be, I think the show was a thrill.

At the opening, were visitors from Amsterdam photo circles. It was huge validation to welcome knowledgeable folk venturing such a distance from their reliable cultural locale. Another indicator of legitimacy.

I am grateful the show was a success. Prior, I didn’t think about it; I didn’t know how to define success with a show. And I don’t know what I’d have done if it had been a flop!

I’m happy for all the beautiful staff at Noorderlicht that it has worked out. Hester and I were treated like family. That’s not an exaggeration – I’ll leave you with the words of Ton Broekhuis, Noorderlicht Foundation Director as written to me in an email following my return to the U.S.

“Pete, you mentioned ‘being welcomed into the Noorderlicht family’. You did not mention leaving the Noorderlicht family, which is reasonable. Everyone who joins the family by free will makes – at the same time – a promise to come back. Family is family. It is forever.”

PRESS FOR CRUEL AND UNUSUAL

American Photo: “There’s a wide range of photography blogs on the internet, but how would it be possible to measure their impact on the real world? It’s difficult to see the offline effect of an idea published online. […] We’re interested to see what other ways photography bloggers choose to usher their projects into the real world, and Brook certainly sounds excited. “This is going to sound crazy,” he said, “but I’ve never seen these works any bigger than 600 pixels wide on a screen.” Spoken like a true 21st-century curator.”

Elizabeth Avedon: “Noorderlicht Gallery is producing a ‘must-have’ catalog for Cruel and Unusual, designed as a newspaper by Pierre Derks in an edition of 4,000. Along with visuals from the main exhibition, the catalog contains articles, interviews, ephemera and material from photographers Pete Brook encountered during his crowd-funded road-trip through the U.S.” (One and Two and Three)

Daylight Magazine: “What steps are being taken to productively rehabilitate inmates, rather than simply secluding them from society and releasing them once their term is up? The Nooderlicht Photogallery has curated a show from nine women photographers to explore the effect that mass imprisonment has had on our sense of justice and virtue.”

Marc Feustel: “Brook and Keijser write two of the most dynamic and esoteric blogs that you will find on the web. To state the obvious, prisons are not exactly a sexy subject and the fact that they have managed to put this show together is very impressive. Instead of a ‘traditional’ exhibition catalogue, the curators have put together a newspaper in an attempt to reach more readers than an expensive photobook could. The world of photography online can be an exasperating, sprawling mess, but the fact that it can lead to projects such as this one makes it genuinely worthwhile.”

Stan Banos: “If you’re interested in documentary photography and interviews with the top notch photographers who made the work, Cruel and Unusual [newspaper] is very much worth the look.”

Greg Ruffing: “How citizens (aka taxpayers) understand the prison system and life behind bars, and how do they formulate their thoughts and convictions about mass incarceration based on the information they receive (and where that info is filtered through)? Cruel and Unusual gets to the heart of that issue by examining how prisons and prisoners are presented in images, and how those images are created, distributed, and consumed.”

Colin Pantall: “It is testament to how the internet and blogs are having a real impact that is breaking new ground and making new visual discoveries and connections.”

No Caption Needed: “Cruel and Unusual will provide another occasion to consider how the carceral system condemns those within and without, and how photography can reveal and build relationships where before there was only confinement, within and without.”

re-PHOTO: “Regular readers will know that I’ve often mentioned Pete Brook’s Prison Photography blog on these pages. He’s someone who has often raised interesting issues, both photographic and political, and the forthcoming show Cruel and Unusual at Noorderlicht which he is curating together with Hester Keijser looks to continue in that vein.” (One and Two)

Lens Culture

Eastern Art Report

La Lettre De La Photographie

Wayne Bremser

GUP Magazine

Dutch Press

FotoExpositie

FocusMedia

PhotoQ

Hamburg Art & Culture blog

Dutch free daily, De Pers ran a double spread of Scott Houston’s Arizona Female Chain Gang work. Dutch and Google translated English.

Noorderlicht has links to the De Pers article as a PDF and also a PDF of the Vrij Nederland feature on Alyse Emdur’s work (Dutch only)

Hester did three interviews for Dutch Radio

Radio Netherlands Worldwide

NOS, Netherlands Public Radio (Dutch only)

VPRO, Netherlands Public Broadcaster (Dutch only)

*Auto-Press*

Hester with the announcement and the backstory, and Hester reflecting on the churn that was newsprint catalogue design and production.

Prison Photography: Announcement, thoughts on the newsprint catalogue, newspaper distribution.

And finally, a Feature Shoot interview I did with about how the road-trip and exhibition have shaped the Prison Photography “Project”.

“What’s done we partly may compute, But know not what’s resisted.”

– Robert Burns, Address to Unco Guild

I recently benefitted to the tune of $11,215 (less the 8.5% taken by Kickstarter and Amazon) to do Prison Photography on the Road. It was one of the most exhilarating and productive experiences of both my life and work.

Since completing the road-trip, I have postponed the publication of the remaining PPOTR audio and the delivery of incentives to funders. This is due to the time required preparing for Cruel and Unusual, an exhibition that I consider an extension of the PPOTR mission.

I let funders know about this delay, but I am still a little uneasy.

This week, I spotted a couple of pieces published about crowdfunding.

Matt Haughey wrote Lessons for Kickstarter creators from the worst project I ever funded on Kickstarter.

The lesson here isn’t necessarily avoiding the mistakes Matt details because the mistakes were specific to the particular project. Rather, know that if you promise something on the internet to potential funders, you had best be able to deliver. Success AND FAILURES will be shared as widely as you originally cast the net for funding.

Matt’s piece was about process and about communication. Joerg Colberg’s article Crowdfunding is Not a Cash Cow is a bit about communication, but more precisely about relationships based upon transaction. Joerg:

“Artists need those relationships. In the past, these kinds of relationships were usually established with wealthy collectors only. Now, crowdfunding offers the chance to establish them with a much larger, much more diverse, much more democratic group of people.”

Joerg urges creators/artists to think of funders as patrons and not “cash cows”, that is that they might come back a second time if they feel you were straight, delivered on your promises and valued the relationship.

That’s pretty much been my position throughout PPOTR; not necessarily that people would come back a second time to give me more money, but that they’d come back a second time to have a conversation.

For people involved in such activities, making art or photographs or writing forms the basis of how people measure ones integrity. All of that is put to one side when you meet someone in person. Their measures of your integrity are now based on how you introduce yourself, how you engage them and how much you value the interaction. Appealing for crowdfunding is like introducing yourself to the world and winning funding is beginning a friendship.

I’ve been asked a lot about advice on how to mount a successful Kickstarter and up until now I’ve felt uncomfortable giving tips on the nuts and bolts of a campaign. That’s because crowdfunding is much more than that; crowdfunding is personal, it’s gut- instinct, it’s sometimes spontaneous and it’s about friendship and respect.

So, these are not the rules per se for crowdfunding. This is the etiquette of crowdfunding. Which, for me, are one and the same.

1. Make a blooming good video.

This is your elevator pitch. 30 seconds. Probably 2 or 3 minutes. Maybe 5.

Without a good pitch few other things can happen.

Anticipate the widest audience; explaining your project to people who’ve never heard of you and simultaneously to your longtime friends is tricky. Be clear and passionate. Let potential funders know why you’ve the skills to carry through the project better than anyone else. Not easy in just a couple of minutes.

2. Search out honest advice.

BEFORE

Seek advice from people in the know. For me, I contacted 20 other photobloggers and asked if they thought my plan was viable. They all said “yes” or “don’t know, but I’d be interested to see you try.” Without their support, I’d not have pitched PPOTR on Kickstarter.

DURING

Ask a trusted friend to tell you if your video pitch makes sense. You need to know if it represents your idea in the best possible way. I find it very difficult to establish distance from my work. Things I take as given are not familiar to everyone. People unfamiliar with your area of work need to be compelled enough by the pitch to buy in.

AFTER

Ask for feedback as your project comes to a close. Hopefully your funders will be happy with your efforts and relationship. If so, pat yourself on the back. If they’re not, you will still benefit from their feedback and from the honest-note you close on.

3. Incentives should be personal, imaginative, exclusive and offer potential funders a wide array of funding levels.

Be creative, even funny. Try to be non-virtual. Snail mail still exists. I underestimated the simple postcard but PPOTR funders loved them! The same goes for hand made art and prints.

People could back PPOTR with any amount between $1 and $1,750. This range is not unusual and often goes higher.

4. Have a really strong set of existing networks.

Cold calls don’t work at the best of times, and here they’ll just be a thankless time sap.

5. Be prepared to promote the crap out of it.

For a full month, I promoted PPOTR like it was a part-time job. Answering calls, sending emails; requesting info; co-ordinating photographers involved; doing interviews; keeping people updated on progress.

6. Involve the community.

If you’re asking for community funding then involve the community.

Firstly, it’s much more fun. Obviously, some projects are more suitable than others for community involvement. It was much easier for me to involve folk because I proposed interviewing scores of photographers, I slept on people’s couches, and I relied on prison photographers to provide the high-end Kickstarter incentives.

Another advantage to this is that all those people you involve will promote your project in their networks.

7. Be realistic about the amount of time and energy it will take to deliver the incentives.

I totally underestimated the time it’d take to write a postcard to every single funder. While on the road, with a little help from friends, I managed to send 100. But I still have 60+ to do and I consider myself fortunate that I’m currently in exotic climes such as the UK and Holland from which to send unique cards. Better late than never.

8. Treat your funders like royalty.

Folk have said they kept up partly with PPOTR via Facebook and Twitter. But folk are not funders.

From the start, I was adamant that ONLY funders would have access to behind-the-scenes information. I published the most complete updates through the Kickstarter website. It was important to me that funders saw my road diary as written for them and them only.

It would have probably benefitted me and my visibility online (on which I rely for maintaining a reputation) if had I made my diary public on Prison Photography blog. BUT, to do so would not have directly benefitted the trip.

By providing exclusivity to funders, I was investing in a select number of relationships.

9. Only ever do one Kickstarter.

I’ve made this “rule”, mainly for myself, since finishing PPOTR.

Partly, because planning a project, designing the pitch, launching and promoting it, completing the work, maintaining relationships with your funders and then delivering on the final product(s) is A LOT of work.

Partly, also it’s about image. You don’t want to appear greedy or entitled. For me, going back for more would look a bit tacky. That’s a personal opinion – more of a feeling – and I wouldn’t be able to debate it at length.

Any thoughts and any questions don’t hesitate to raise in the comments.

Print of Mumia Abu-Jamal portrait by Lou Jones. During the PPOTR interview at his Boston studio, Jones said when he made the portrait it was the first time in 5 years that Mumia had been photographed without shackles on his wrists.

Prison Photography on the Road concluded at approximately 11pm, December 20th.

I’m hugely privileged to have had the opportunity to hit the road and throw myself, an audio recorder, and a sleeping bag at my intellectual passion.

On the 21st December, I hopped aboard a flight bound for holiday cheer, cask ale, mince pies, friends and family in the UK. With Christmas in Yorkshire and New Year in Scotland, I’ve enjoyed an extended period of down-time and in many ways needed that time to digest all that was achieved during PPOTR. And, now, I must responsibly and efficiently share what was learned and gained.

I anticipate 2012 to be a year of flux. I’ll be experimenting with new ways of sharing information. I don’t want to disclose too much at this point as many projects remain in planning stages. Still, expect a shake up here at Prison Photography.

Whilst I get to work, I thought you’d be interested in some figures that in some small ways indicate the parameters and spirit of the trip.

RUNNING THE NUMBERS

12,333 miles total

1,443 image files made with the Lumix digital camera

762 miles – longest drive in a single day (Salt Lake City, Utah to Kearney, Nebraska)

500+ people I spoke with and exchanged ideas

374 gallons of petrol

155 CDs played on car stereo

120 cups of coffee

103 different wi-fi connections

100 postcards sent (at time of writing, number set to increase)

90 days and nights

78 showers

71 pet cats and pet dogs I met

67 interviews (3 interviews every 4 days)

46 destination cities

39 photographers

31 states

28 criminal justice reform experts/advocates

18 ruby Texas grapefruit

16 batteries spent

6 lectures delivered

4 oil changes

3 prisons visited

2 hotels

2 nights sleeping in the car (New York; Arizona)

2 parking tickets (Milwaukee; San Francisco)

1 night camping (in an Iowa thunderstorm)

1 Occupy Movement protest march (Philadelphia)

1 speeding ticket

1 arrest

0 car problems