You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Photography’ category.

The Oracle gathering? An International Mob of Mystery? Well, not exactly but given that Oracle is the main meeting of the world’s most influential people in the museum/fine art photography scene it is amazing the gathering flies under the radar year on year.

I’ve done some internet sleuthing to tell you some of what you need to know about the Bilderberg of the photography world.

Okay, it might not be so cloak and dagger as I have set it up, but The Annual International Conference for Photography Curators dubbed ‘Oracle’ has no web presence and no connection to the circles outside of the attendees. This (presumably intended) detachment is – simply put – a shame. Granted, these are people predominantly involved in museum curating, but still wouldn’t it be great to know what they are talking about when they meet each November?! Museums still feed into the photography ecosystem, and often define it.

Oracle began in 1982 as an informal gathering. In 2003, Deidre Stein Greben wrote, “Attendance at Oracle […] has grown from ten to more than 100 over the last 20 years.”

With such an organically unhurried growth, why should curators care to share their dialogues? Hell, the week might be the closest thing many of them get to a holiday. Add to that the fact that there’s no external promotion or grand narratives to push, it makes sense that no-one would take on the extra workload of interfacing with the public and all that entails.

I also think of photography curators as a similar breed to university professors; the culture of research, writing and custodianship of department agendas does not dovetail with blogging the discoveries and knowledge from their daily work. (David Campbell summarises well how the reluctance of universities to adopt social networking is to their detriment.) It’s a shame. How good would a Sandra Phillips blog be?!

The 2010 Oracle is ongoing right now in Israel (Jerusalem, I think).

This is where my sleuthing gets patchy but other host institutions/cities have included; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (1992); George Eastman House, Rochester (1993); Washington (1999); Finnish Museum of Photogaphy, Helsinki (2000); Goa, India (2003); Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago (2004); Artimino, Florence (2005); Prague, Czech Republic (2006); Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, AZ (2007) and Paris, France (2009).

My guess is attendance is invitation only or some approximation thereof. Just because I gleaned a smattering of names, I’ll share them. Attendees have included Britt Salvesen, Director of photography and prints at LACMA; Doug Nickel, Professor of Photographic History at Brown University; Sunil Gupta, Artist, photographer, curator and educator; Allison Nordstrom, Curator of photography at George Eastman House; David E. Haberstich, Associate Curator of Photographs at the Smithsonian; Celina Lunsford, Director of the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt; Olivia Lahs-Gonzales, Director of the Sheldon Art Galleries in St. Louis; Dr Sara Frances Stevenson, Chief Curator of the Scottish National Photography Collection, National Galleries of Scotland (retired); Mary Panzer, freelance writer & curator of photography & American culture; Ms. Agne Narusyte, Curator, Vilnius Art Museum Photographic Collection, Vilnius, Lithuania; Shelly Rice, Professor of Arts at NYU Tisch School of Arts; Enrica Viganò, curator and fine art photography critic; Duan Yuting, founder of the Lianzhou International Photo Festival; Mark Haworth-Booth, Head of Photographs, Victoria & Albert Museum; Anne Wilkes Tucker, photography curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Sandra S. Phillips, Senior Curator of Photography at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Quite the list. And I can think of many other photography curators who presumably would attend (Rod Slemmons, Anthony Bannon, Brian Wallis, Charlotte Cotton, Malcolm Daniel?) Who knows?

It’s not a totally closed shop though. Despite the 2006 shuttering of the Oracle listserv, some plucky “Independents” have set up a NING type forum, Oracle Independents. It is sporadically updated with links to articles and events about historically significant photography. Currently there are 40 members, some names recognisable. But this doesn’t get us to the meat of those dialogues currently ongoing in Jerusalem.

Last thing to say, is that the museum world is separate from the worlds of gallery, photojournalist, fine art, auction house, social documentary, magazine, fashion and art-school photographies. Even if we did have a line in on the world’s leading curators’ discussions, the information may have no bearing on our aims, art or careers. Heck, we might not even be interested. But it’d be nice wouldn’t it?

Not wanting to be pessimistic, but unable to help myself, consider this quote from Marvin Heiferman, freelance author, editor and curator and “champion of the blue-collar nature of the silent majority of photographs.” Bear in mind he’s talking about very early Oracle, but nonetheless, the quote highlights potential disconnects between different orbits of the photography world.

“When I started looking at this new [Postmodern] work, I loved its nonchalance, intelligence and cheekiness, the fact that it was interested in both seeing and seeing through images. The photo world, though, wasn’t as amused, and didn’t have a clue what the small group of us was getting so jazzed up about. Toward the end of my stint at Castelli in the early 1980s—and then when I went off on my own to work with photographers and artists and produce exhibitions—I attended some of the early annual meetings of Oracle. This was a conference of photography curators from around the world who gathered together supposedly to talk about the future of the field, and was funded by Sam Yanes at the Polaroid Corporation. Polaroid supported a lot of progressive photographic projects in the 1970s and ’80s. It was, to say the least, disappointing to me that most of the attendees were more excited to fuss over 19th- and 20th-century work and issues of preservation and storage. But there were a handful of us—including Andy Grundberg, who was writing for the New York Times, and Jeff Hoone from Syracuse—who did our best to raise interest in the new work we were so excited by. No one seemed to care.” (Source)

“SnapScouts was designed and developed for children to use, before they form stereotypes of other people. They’re the perfect reporters, unbiased and unprejudiced by media concepts.”

“[SnapScouts] leverages modern technology to address the timeless threats to democracy and freedom.”

THIS is one of the best pieces of satire in a long time, at least I think, I hope, I know it is satire.

A NEW WAY OF EARNING BADGES

From SnapScouts:

Want to earn tons of cool badges and prizes while competing with you friends to see who can be the best American? Download the SnapScouts app for your Android phone (iPhone app coming soon) and get started patrolling your neighborhood.

It’s up to you to keep America safe! If you see something suspicious, Snap it! If you see someone who doesn’t belong, Snap it! Not sure if someone or something is suspicious? Snap it anyway!

All this is a great play off America’s worst paranoia and best humor. Good stuff!

The FAQ page is hilarious combining fears of soft drugs and illegal immigration with a contempt for foreign CCTV culture.

“My eight-year old caught the gardener smoking something suspicious. It wasn’t marijuana, but it turns out he was illegal!” – Phyllis Specter, 32, Idaho

and

“After only a three-month trial of SnapScouts in England, Indonesia, and Germany, we are proud to report over 600 crimes reported.”

On 26th July 2010, Comrade Duch, the chief executioner of the Khmer Rouge will finally face justice. A verdict is due to be passed down in the trial of Duch who is charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity for his part in the deaths of up to 12,000 Cambodians.

Duch’s trial would not be possible if photographer Nic Dunlop had not tracked him down in 1999. The story is told in Nic’s book The Lost Executioner.

Dunlop says, “It’s a strange thing to think that a chance encounter eleven years ago in a remote village has led to a multi-million dollar trial involving dozens of legal experts, academics, victims, perpetrators and journalists. But it is disappointing that only one man has been tried for these crimes in more than 30 years.’

(via)

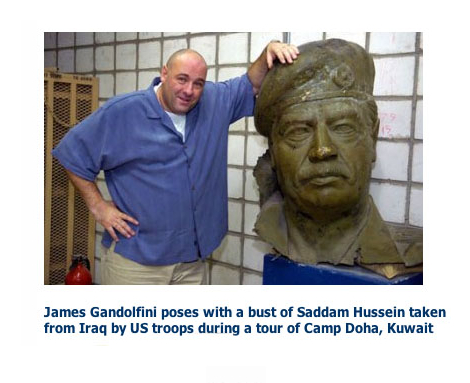

Spread from Toppled

Toppled by Florian Göttke

Two weeks ago, Foto8’s Guy Lane reviewed Toppled by Florian Göttke. The review is what it is – a description of Göttke’s “(mainly) pictorial study of the destruction, desecration and mutation of many of Iraq’s plentiful statues of its former dictator.”

Lane’s conclusion points to the significance of Göttke’s study:

“Perhaps this might all appear somewhat peripheral, an iconographical diversion from the real business – invasion, subjugation, and expropriation – of Occupation. But from amongst Göttke’s collated written testimonies and reports, it is possible to sense something of the importance that was attached to the Coalition’s iconoclasm. For example, a BBC account of British activities in Basra concluded that ‘the statue of Saddam is in ruins. It is the key target of the whole raid.’ Meanwhile, in Baghdad a US army captain was ordered to delay destroying a statue until a Fox TV crew arrived. Most famously, the Firdous Square episode appears to have been – to a degree – choreographed for the benefit of the foreign media based in the overlooking Palestine Hotel. ‘American and British press officers were indeed actively looking for the opportunity to capture the symbolic action of toppling statues and have the media transmit these to the world,’ writes Göttke. As such, Toppled’s events and pictures correspond tellingly and damningly to the Retort group’s analysis of our ‘new age of war’.”

Would I buy the book? Probably not. The book is a concept. I understand the concept. And, the images are essentially props to the concept (illustrations of the new biographies of statues, of things).

Besides, I can get my fill elsewhere. The best (most ridiculous) image – James Gandolfini meets the Butcher of Baghdad – is on the accompanying Toppled website.

SADDAM’S PERSONAL PHOTO ALBUM

Göttke’s work leaves me wondering how Saddam’s personal photo-album fits in?

Similarly, these images were found and taken during the invasion of Iraq: “On the night of June 18, 2003, the soldiers in the 1-22 Infantry stormed a farm in Tikrit, Iraq, hoping to find a fugitive Saddam Hussein. They didn’t find their target, but they did find a consolation prize: Saddam’s family photo album […] When he returned from Iraq, Lt. Col. Steve Russell, the commander of the 1-22 Infantry, donated the album to the National Infantry Museum at Fort Benning, Ga.” (Source)

This is a reversal, no? Not the effigies of megalomania, but personal snapshots. Not public monstrosities but flimsy two-dimensional depictions. Would these have got pissed on and slapped with sandals? Would they have been torn up/burned up had Lt. Col. Steve Russell not slipped them into his luggage?

Also, to describe the collection (for media publication) as the dictator’s “personal album” is one thing, but to what extent were these Saddam’s photo-memories? Are these really the contents of an album he valued? Are we even glad that Saddam’s images still exist?

One final thought, how do we distinguish between the staging of Saddam’s images to the staging of the images in Göttke’s survey?

JAMAL PENJWENY

On a less-grander scale, Jamal Penjweny is attempting (with his Iraqi subjects) to make sense of the spectre of Saddam. The series is called Saddam is Here. It’s not great photography but I don’t think this type of playful exploration needs to be.

© Jamal Penjweny

Clearly, Alec Soth does know what he is talking about … and he talks a lot of sense … and he talks often.

Last week, however, Magnum Photos attributed this quote to Soth and twatted it into the webiverse:

“It’s not about making good pictures anymore. Anybody can do that today – it’s about good edits…”

Thus a medium-sized discussion ensued on the Fraction Mag Facebook page covering the need for outside perspective, audience expectations, technologies beyond those of cameras but of distribution also, etc, etc …

I wanted to know why and when Soth said this and in what context he made the statement. I emailed him. Here’s his response:

Dear Pete,

I don’t when or in what context this comment was made or if it was made at all. Nor do I know who posted it. But this itself is quite telling, isn’t it? Are people interested having serious discussions about miscellaneous, fragmentary tweets? I would much rather talk about a fully realized interview or essay. In a similar way, I’m much more interested in edited projects than I am in isolated images.

Best,

Alec

I don’t know if we should now discuss this fragmentary correspondence or just leave it alone?

Alfie Brooks (not his real name) is the focus of Amelia Gentleman‘s recent Guardian article. Photographer Tom Wichelow spent 12 months with Alfie documenting his life:

During those 12 months, Alfie was sentenced to eleven days in prison (for stealing 400 balloons). It was his first stay in prison. Alfie intends it to be his only stay in prison. He was bored.

A coffee table at his flat, on which are instructions on how to use the curfew tag he has to wear. © Tom Wichelow

To the journalist, Alfie is simultaneously endearing and frustrating; he delivers pearls of wisdom and then childish logic. More startlingly, sometimes the two are the same – and we, the reader, need to rethink our perceptions and expectations of a younger generation without the same future-oriented behaviours we value and reward.

Alfie is affable and greeted warmly by folk about his hometown. He isn’t violent and has never stolen from an individual, only shops. It is a code he justifies. He has also smoked marijuana for as long as he can’t remember:

AMELIA GENTLEMAN

For me, Gentleman’s piece is not a ground-breaking piece of journalism, but it is unique. It takes the time to look at a young life that could be the norm for more young lives than we’d like to admit. It really spells out for us the drifting uncertainties of life for youth who’ve opted out of formal education, but are still bright, articulate, playful and “clear with ambition”. Gentleman has a fondness and hope for Alfie which is appropriate and understandable.

TOM WICHELOW

Gentleman’s piece is well supplemented by Tom Wichelow’s photo essay, A Year in the Life of Alfie Brooks. His year long study of Alfie is a nice counterpoint to other work in his portfolio, notably his work on CCTV in the Whitehawk housing estate, Brighton, You’ll Never be 16 Again and 2000 portraits.

Relation, 2001 [from “Vestige”] © Riitta Päiväläinen

Anyone else notice Shane – over the weekend – spewing out content quicker than BPs worst nightmare?

And what quality. In two days we had:

Timothy Briner: Boonville

Thomas Bangsted: Pictures

Sasha Bezzubov: Wildfire

Céline Clanet: Máze

Ralph Shulz: Theater

Charles Fréger: Fantasias

Riitta Päiväläinen: Vestige

Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk: The Andromeda Strain

Good stuff.

Fantasias 9, 2008 [from “Fantasias”] © Charles Fréger

Over two million individuals are behind bars in U.S. prisons, living in isolation from their families and their communities. Prison/Culture surveys the poetry, performance, painting, photography & installations that each investigate the culture of incarceration as an integral part of the American experience.

As eagerly as politicians and contractors have constructed prisons, so too activists and artists have built a resistance. Nowhere are these two forces pushing against one another as forcefully as in California. The book, Prison/Culture, compiles the documents of a two year collaboration between San Francisco State University, Intersection for the Arts (one of San Francisco’s oldest art non-profits) and prison artists & outside activists across the US.

Mark Dean Johnson’s essay summarises the visual/cultural history of incarceration; from Gericault’s institutionalized mentally ill subjects and his paintings of severed heads as protest against capital punishment, to Goya’s prison interiors of the inquisition; from Alexander Gardner’s portrait of Lincoln’s assassin Lewis Payne (1865), to Otto Hagel’s portrait of Tom Mooney (1936); and from Ben Shahn’s murals against indifference to the conditions of immigrant workers (1932) to the work of Andy Warhol and David Hammons in the modern era.

Johnson guides this lineage to the Bay Area, describing how Michel Foucault’s book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison became the conversation topic of Bay Area coffeehouses and classrooms (Foucault began lecturing at UC Berkeley in 1979). The swell of interest in Foucault’s structuralism coincided with a grassroots expansion of prison art in the early 1980s.

For text, the editors of Prison/Culture made two canny and provocative choices: Angela Y. Davis and Mike Davis (no relation).

THE TEXT

Firstly, in a 2005 interview, America’s most notorious prison abolitionist Angela Davis sets out – in her most accessible terms – how our prison industrial complex serves primarily as a tactical response to the inadequate or absent social programs following the end of slavery. Abolition was successful in that it redefined law, but it failed to truly develop alternative, democratic structures for racial equality. Powerful stuff, yet even newcomers to Davis’ argument won’t be as shocked as they may expect to be. She’s that good.

Next up, Mike Davis’ 1995 essay ‘Hell Factories in the Field’ is a bittersweet ‘I-told-you-so’-inclusion. Davis has made a specialty of dealing with – in stark academic prose – disaster scenarios, race-based antagonism and the environmental rape of recent Californian history. When Davis witnessed the mid-nineties expansion of the prison industrial complex (or as Ruth Gilmore Wilson terms it ‘The Golden Gulag’) he foresaw prisons’ economic band-aid utility for depressed towns; foresaw the mere displacement of violence; foresaw the assault on fragile family ties; foresaw the unconstitutional prison overcrowding and predicted the collective collapse of moral responsibility.

Davis’ article focused on the then new California State Prison, Calipatria – and not in a dry way. Paragraphs are devoted to recounting the installation of the world’s only birdproof, ecologically sensitive death fence following impromptu electrocutions of migrating wildfowl. The editors note, as of 2008, Calipatria’s facility design of 2,208 beds was 193% over-capacity with 4,272 inmates. Where birds saw an improvement in their lot, prisoners certainly did not, have not.

THE ART

Contributors include some well-known names – RIGO, (here on PP) Sandow Birk, Deborah Luster and Richard Kamler whose works address incarceration, criminal profiling, wrongful conviction, prison labor, and the death penalty. The book also includes poetry by Amiri Baraka, Ericka Huggins, Luis Rodriguez, Sesshu Foster and others but I shall not comment on these wordsmiths (their work is beyond my purview) other than to say they are talented and politically in the right place.

Special mention must go out for Deborah Luster’s One Big Self project (more here). In my personal opinion, it is the single most important photographic survey of any US prison. It is certainly the most longitudinal. Over a five year period, Luster visited the farm-fields, woodsheds, rodeos and national holiday & Halloween events throughout Louisiana’s prisons. She became a loved and recognized figure among the prison population; she estimates she gave away 25,000 portraits to inmates. Luster’s conclusion? Even mass photography struggles to communicate the vast numbers of men and women behind bars.

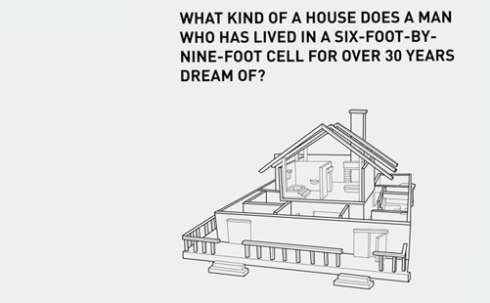

In 2003, artist Jackie Sumell collaborated with Herman Joshua Wallace (one of the Angola 3) on the design of his “Dream House”. The project The House That Herman Built is heartbreaking and bittersweet.

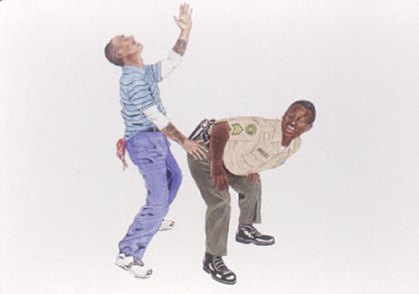

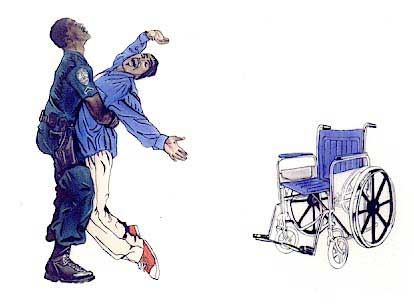

Alex Donis employs cunning and cutting humour for his series WAR. He sketches criminal “types” with figures of authority (policemen, prison guards) mid-dance, often bumping and grinding. He even conjures a kiss between Crips and Bloods gang members.

Also unexpected is the visual testimony of condemned mens’ last requested meals. For The Last Supper, Julie Green painstakingly painted porcelain plates with the last meals of nearly 400 executed men. Grayson Perry won the Turner Prize a few years ago, in large part due to his vases of abuse, bigotry and social ills. This clever use of regent materials has also been adopted by Penny Byrne for her Guantanamo Bay Souvenirs which sets up interesting parallels and a new turn for discourse between US homeland prisons and those used for the “Global War About Terror” (GWAT).

Relating to GWAT, Aaron Sandnes established a sound sculpture in which gallery visitors were subjected to the same pop songs used in Psych-ops by police and military interrogators.

Dread Scott‘s use of audio is intentionally to give silenced men a voice. (Scott has talked about the primacy of audio in his exhibition of prison portraits previously at Prison Photography).

Mabel Negrete collaborated with her brother incarcerated in Corcoran State Prison. She mapped out the floorplan of his cell as compared to her apartment bathroom. She then developed a dramatic dialogue in which she played both herself and her brother. (No images unfortunately.)

Traced – but essentially fictional – lines of structure are fitting for San Francisco, the city in which world-famous architect/installation artists Diller & Scofidio got their start with the architectural memories of the Capp Street Project. Negrete’s CV is extensive, she was instrumental in organising Wear Orange Day, a prisoner awareness action. Also check out her Sensible Housing Unit.

Cross-prison-wall collaborations are vital to the project as a whole; so much so, that without input from prisoners, the entire enterprise would fall short. Primarily, it is the men of the Arts in Corrections: San Quentin run by the William James Association who deliver acrylics and oils of optimistic colour and profound introspection. More here.

Collaboration as delivered in a multimedia and digital format comes by way of Sharon Daniel’s Public Secrets. Public Secrets “reconfigures the physical, psychological, and ideological spaces of the prison, allowing us to learn about life inside the prison along several thematic pathways and from multiple points of view.”

In closing, it is worth noting that San Quentin prison (only 12 miles north of San Francisco) has one of the few remaining prison arts programs in the state following 20 years of cut backs. The works in Prison/Culture challenge – as Deborah Cullinan & Kurt Daw, in their foreword, suggest – “traditional boundaries between inside and outside, between professional and amateur, between institutions and people” and, “by juxtaposing work by professional artists with artists who are working inside a prison, this book challenges us to rethink notions of community and culture.”

Prison/Culture is simultaneously a consolidation of achievement, a fortification of resources and celebration of resistance. This may be a book with a Californian focus, but it has national and international relevance. Succinct, well researched, egalitarian and lively. For me, Prison/Culture is the best collection of works by any US prison reform art community up until this point in history.

The resource list of over 80 organisations at the back of the book (page 92) is ESSENTIAL reference material for anyone looking to commit energies into prison art programs. All told, this book is a must read for those interested in the artistic landscape of our prison nation. It powerfully exposes the vast gulf between criminal justice and social justice in US society.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Prison/Culture is published by City Lights, edited by Sharon E. Bliss, Kevin B. Chen, Steve Dickison, Mark Dean Johnson and Rebeka Rodriguez.

Read a Daily Kos review here, and view images from a 2009 exhibition here.

City Lights Celebrates the Release of Prison/Culture

On Thursday, May 6 at 7:00 pm, join Steve Dickison, Jack Hirschman, Ericka Huggins, and Rigo 23 for a reading and book release celebration at City Lights Books. Tune in to KQED Forum at 9:00 am PDT the morning of the event for an interview with the book’s editors and contributor Angela Davis.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Images (from top): PRISON/CULTURE book front; Sandow Birk; Deborah Luster; Exhibition views of The House That Herman Built; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Julie Green; Julie Green; Ronnie Goodman, San Quentin inmate, displays his work; and ‘Public Secrets’ screenshot.