You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Visual Feeds’ category.

Screengrab from the San Mateo County Sheriff’s webcam of jail construction.

I always say that I’m open to looking at all types of prison imagery, so I guess I’m obliged to mention the 24-hour coverage of a prison that does not yet exist. (It’s a first for Prison Photography.)

The San Mateo County Sheriff’s Department in California has set up a webcam to track construction of the county’s new jail. Why? Maybe the Sheriff was buoyed by the popularity of Panda Cam at the San Diego Zoo, Condor Cam in California, or Portland’s Osprey Cam?

The live feed is “an innovative and exciting way to involve the public,” said Sheriff’s Office spokeswoman Rebecca Rosenblatt said.

Slated for a 2015 opening, tax payers can watch the construction of Maple Street Correctional Center in Redwood City. I suppose if you’re forking out $165 million for a jail, you want to see your money being spent?

The truth is this webcam is pitiful reminder of California’s budget woes and political battles over prison management and spending.

There’s an argument that a new jail is necessary due to California’s ongoing “Realignment” — a court-mandated program whereby state prisoners are being transferred to county jails in order to comply with federal orders to reduce the state prison system by approximately 32,000 prisoners.

That decision came about after a decade long legal battle — that went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States — ruled that the overcrowding in the California state prison system led to inadequate physical and mental health care and an estimated one preventable death every 10 days. As a result the prison system was deemed “cruel and unusual” in its punishment and is in violation of every single California prisoner’s constitutional rights.

Unfortunately, Governor Brown refused to look at strategic release programs for non-violent offenders, at compassionate release for elderly and terminally ill prisoners or at drug treatment programs to ease overcrowding. Instead, Brown raided the state’s budget surplus — to the tune of $315 million — and will start paying private prison corporations to warehouse prisoners.

Money pouring into new jail construction. The indubitable Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB) report:

“In addition to AB109 realignment money, Sacramento has offered two funding streams that encourage county jail expansion and has refused to offer incentives for thoughtful decarceration. AB 900 authorized $1.2 billion in lease revenue bonds for the construction or expansion of jails, and SB 1022 authorized $500 million for jail expansion. If realignment is to be successful, the state must support counties to reduce their jail populations, rather than making plans to grow them.”

In time, the San Mateo Sheriff’s Office plans to release a time-lapse video of the creation of the 280,000-square-foot jail grow from start to finish.

via the usually useless SF Examiner

IVY LEAGUE LAW GRADS MAKING FILMS?

Following up on Monday’s post The 20 Best American Prison Documentaries, I wanted to highlight the Visual Law Project out of Yale University.

The project runs “a year-long practicum at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School that trains law students in the art of visual advocacy — making effective arguments through film.”

I’d think being a law graduate and then a real world lawyer would be enough; one expects visual journalists or documentarians to have this sort of territory covered. Perhaps not? Never too many advocates or concerned observers, right?

There’s more answers on the FAQ page:

Q: Why should law students learn visual advocacy?

A: Visual and digital technologies have transformed the practice of law. Lawyers are using videos to present evidence, closing arguments, and victim-impact statements; advocates are making viral videos to advance public education campaigns; and scholars are debating ideas in a multimedia blogosphere. Everyone’s doing it. But no one is really teaching it — or reflecting upon it. We see training in visual advocacy — effectively evaluating and making arguments through videos and images — as a vital part of our legal education.

Of the films the VLP has produced The Worst Of The Worst is of particular interest to me. One can be lax and think that solitary confinement is a brutal practice prevalent only in California, New York, Illinois and other large states, but every state has at least one SuperMax including the seemingly genteel Connecticut.

The Worst of the Worst takes us inside Northern Correctional Institution, CT’s sole supermax prison, and includes interviews with a range of experts and administrators are interwoven with the stories of inmates and correctional officers who spend their days within the walls of Northern.

From the trailer, the treatment of the correctional officers and prisoners seems sympathetic. This gives me hope; it suggests the problem is the fabric of the facility which prohibits rehabilitation, rather than a presumption of fault or inadequacy. Prisons are toxic and often inflexible enough to capitalise on the potential of people who are caged and work within.

Check out the fledgling (est. 2011) student run Visual Law Project.

More here.

Thanks to Larissa Leclair for the tip!

COLORS has been a favourite of mine since their PRISONS Issue #50. By chance I picked up a copy of the Spring 2013 COLORS magazine, Issue #86 MAKING THE NEWS.

Issue #86 is a cracker of an issue: North Korea, Al Qaeda’s film production house, surveillance, Tahrir Square, El Narco Blog, Pakistani drone attack survivors’ photographs, Will Steacy’s photos of a dead Philadelphia Inquirer and James Mollison’s images from Sierra Leone; the issue deals with heavy topics and uncomfortable imagery.

Also uncomfortable, is the scene of Fabienne Cherisma’s corpse atop a collapsed cement rooftop in Port-au-Prince, Haiti on the 19th January, 2010 (one week after the massive Haiti earthquake). The scene was captured by multiple photojournalists, whose images COLORS features over 4 pages. They are online here.

The photographs and the circumstances in which they were made are very familiar to me. Between January 27th and April 8th, 2010, I published a fifteen-part series (beginning here) about the photos and photographers activities. In short-shrift, from a desktop in Seattle, I uncovered the similar photographs by scouring the wires, agency websites and news feeds. I interviewed a dozen of the photographers on scene.

The scene of Fabienne splayed out was — and remains — stark. It is one of the more indelible images to emerge from the natural and social disaster. So, the image was known but it’s dissection and the placement of multiple photographers’ works was done by me. My inquiries accelerated the image and the stories into the public sphere (the posts remain the most visited of Prison Photography; approximately 240,000 page views all-in-all). If my work had not put the story of Fabienne’s death and its photojournalist treatment into the spotlight maybe the awards that came later for three of the photographers would?

I was surprised to make the discovery of those images of Fabienne within the pages of COLORS. More than that, I was bothered. Why was I perturbed? I don’t own the images and I certainly don’t own the story. I’ve not been wronged.

In short, the problem for me is COLORS treatment. They could not have researched the piece without being aware of my 15-part series. COLORS doesn’t deal with the issue in any depth. In fact, they rely on the images to drive the segment and then raise the question of ethics without really providing their own position. Of the images Nathan Weber’s image of the photographers surrounding Fabienne’s body is printed larger and with prominence. Are we incited by the image? Has COLORS forfeited a nuanced handling the images, and thus the story?

Prison Photography was the first to publish Nathan Weber’s image; without doubt that was the image that launched many hyperbolic statements about the depravity of Western photojournalism. So, maybe if I hadn’t contacted Weber directly and asked him specifically about the circumstances perhaps he would never have sent that image to me … or anyone? That’s a question for Weber.

I guess, at heart, I am protective of the story. There’s so many sides to the coverage of Fabienne’s death that I don’t like to see it reduced to an over-simplified “it-was-wrong/it-was-what-it-is” argument. COLORS barely takes us past that.

Finally, I am bothered by COLORS‘ passive use of an abbreviated Weber quote that describes the circulation of the many images of Fabienne thusly:

“Even though grouping together is common for photographers in dangerous situations, many in the international photojournalist community were unhappy with having “their laundry aired in public.”

Prison Photography was the root and the source for the extended debate about these pictures. I brought the issue to the international community. All the feedback that I received for my digging and analysis was, without exception, positive. Readers were thankful to have had the scene looked at from the multiple angles, appreciated my interviews with the photographers, and understood more deeply the complexity of the situation.

No one felt that I was hanging-out photojournalists or photojournalism to dry. Pick any laundry metaphor you wish, it was not my experience reporting the story that people were upset. To suggest that the photojournalist community was irritated by having this public discussion is, frankly, insulting.

Just a quick heads up to let you know that my Instagram handle has changed to my actual name. Find me at @petebrook from now on.

All those past mentions for @p3t3brook are confined to history and will only guide you to a non-existent account. Such is the price to be paid.

Also, remember that time I laid out my Instagram rules? I’ve had a couple of slips, but generally I think I’ve done an okay job sticking to them.

Marie Levin holds a photo of her brother, Ronnie Dewberry, taken at San Quentin State Prison in 1988. Until recently, it was the last photograph he’d had taken. Photo credit: Adithya Sambamurthy/The Center for Investigative Reporting

STARVED OF THEIR OWN IMAGE

We are now into the second week of the California Prisoners Hunger Strike. It is difficult to get firm figures on the number of participating prisoners. The Los Angeles Times reports 30,000; CNN reports 12,000 and Yahoo reports 7,000+.

I’m inclined to trust the figures sourced by Solitary Watch:

The hunger strike began on July 8th with participation of approximately 30,000 people in two-thirds of California’s prisons, as well as several out-of-state facilities holding California prisoners. In the first days of the hunger strike, approximately 3,200 others also refused to attend work or education classes as a form of protest in support of the hunger strike. As of Sunday, there are an estimated 4,487 still on hunger strike.

Still, formidable numbers.

INVISIBLE AND UNPHOTOGRAPHED PEOPLE

Last week, in conjunction with the initiation of the mass peaceful protect, Michael Montgomery for the Center for Investigative Reporting published an excellent article California Prisons’ Photo Ban Leaves Legacy of Blurred Identities about the ban on portrait photographs of prisoners held in solitary confinement.

Accompanying the article is the interactive Solitary Lives feature and a Flickr gallery.

The ban resulted from a tension between what a photograph meant or could mean.

For families, a photograph is a tangible connection to their loved one behind bars, but for staff of the four maximum security prisons that upheld the ban, photographs were potential calling cards — circulated by prison gang leaders — both to advise other members that they’re still in charge and to pass on orders.

The ban was lifted in 2011, following the last California prison hunger strike. Montgomery quotes Sean Kernan, the former Under-Secretary of the CDCR

“I think we were wrong, and I think (that) to this day,” he said. “How right is it to have an offender who is behaving … (and) to not be able to take a photo to send to his loved ones for 20 years?” Kernan directed prison staff to ease the restrictions for inmates who were free of any disciplinary violations.

The ban in the four Californian prisons was extraordinary.

“I have never heard of any other prison system or individual prison in America imposing a long-term ban of this kind,” said David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project.

As I have stated frequently on Prison Photography, prison (visiting-room) portraiture is one of the most prevalent types of American vernacular photography.

Until artists such as Alyse Emdur and David Adler began to draw focus to this disparate, decentralised, emotion-laden, and high-stake vernacular sub-genre, prison portraits were kept in wallets, on mantles and in side tables. There’s tens of millions of them out there.

And yet, for over 20 years, thousands of men in California were not allowed images of themselves. The additional ban of mirrors in solitary units meant that many men often did not see images of themselves for years on end. Again, to quote Montgomery’s article:

“I have asked my husband, ‘Do you even know what you look like?’ And he says, ‘Kind of, sort of,’ ” said Irene Huerta, whose husband, Gabriel, 54, has been detained at Pelican Bay for 23 years.

THE PHOTOGRAPH AS AN OBJECT OF DEPLOYMENT

In the free world, photographs are ubiquitous, easily created, shared and possessed. The fact that these seemingly innocuous objects were caught in the tussle of control between prison authorities and prisoners is astonishing, and speaks to the power struggle (real and imagined) between the kept and the keepers.

Michael Rushford, president of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, said easing the restrictions on prisoner photographs raised no major security concerns, so long as inmates had to earn them. “It’s not as if there’s been an epidemic of inmate photos on the street,” he said.

I am not sure how Rushford would measure this, or even it would significantly alter the lives of prisoners, specifically now during the hunger strike, and especially now when proven or alleged gang affiliations have been put aside by prisoners in solidarity for improved conditions for all.

In light of recent art market fetishism, it would seem the primary reason anyone would want to gather prison portraits would be to repeat Harper’s Books’ $45,000 hustle and cash in on the images?

As for the families (following the ban lift) the value of newly acquired images is not in any doubt:

Seeing an image of their incarcerated relative for the first time in years has sparked renewed hope and revived dormant family connections. For others, the photographs are a shocking reminder of the length of time some inmates have been held in isolation.

CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING LINKS

Michael Montgomery’s California Prisons’ Photo Ban Leaves Legacy of Blurred Identities

Interactive Solitary Lives feature.

A BRIEF NOTE ABOUT THE SOLITARY WATCH WEBSITE

I cannot emphasize enough how important the website Solitary Watch is as a resource. Jean Casella, James Ridgeway, and their team of reporters produce high quality journalism — not only for their website but for other news outlets including The Guardian, Mother Jones, Al Jazeera, Columbia Journalism Review and The Nation.

Solitary Watch is an independent media and advocacy project, funded by grants and donations. It is a project of the Community Futures Collective, a 501(c)(3) non-profit. You can support the project here.

I don’t hesitate to say that Solitary Watch has driven much of the critical and visible public discourse about solitary confinement in U.S. prisons and jails.

As Solitary Watch describes, “Solitary confinement is one of the nation’s most pressing domestic human rights issues — and also one of the most invisible,” which is why I have a vested interest in their work; we’re each interested in making solitary and other egregious aspects of the U.S. prison system more visible.

The NYCLU created a mock prison cell to show what life is like in solitary confinement. Kathleen Horan/WNYC

Today resumed a hunger strike by the prisoners of California’s Pelican Bay State Prison SHU (Secure Housing Unit). In solidarity, prisoners across the nation have also joined.

The main issue at hand is solitary confinement. Namely, its longterm use. UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Juan Mendez, stated that any time over 15 days in solitary confinement constitutes torture. Yet California prisoners have been caged in solitary for 10 to 20 years or more. In addition, the prisoners kept under solitary confinement ask for nutritious food and the same educational programming accessible to prisoners in the general populations of state prisons.

Solitary confinement is an invisible cancer to those outside the system and a terror to those within it.

The prisoners — who refer to themselves at The Short Corridor Collective — are returning to protest that began two years ago. Neither Phase One (July/August 2011) and Phase Two (Sept/Oct 2011) secured the policy changes desired, despite promises from the California Department of Corrections to address the specific issues and reasonable demands made. In 2011, over 6,000 California prisoners went on hunger and work strike making it one of the largest peaceful protests in U.S. prison history.

The Pelican Bay State Prison SHU Short Corridor Collective state:

Our decision does not come lightly. For the past 2 years we’ve patiently kept an open dialogue with state officials, attempting to hold them to their promise to implement meaningful reforms, responsive to our demands. For the past seven months we have repeatedly pointed out CDCR’s failure to honor their word—and we have explained in detail the ways in which they’ve acted in bad faith and what they need to do to avoid the resumption of our protest action.

Five core demands

1. Eliminate group punishments. Instead, practice individual accountability. When an individual prisoner breaks a rule, the prison often punishes a whole group of prisoners of the same race. This policy has been applied to keep prisoners in the SHU indefinitely and to make conditions increasingly harsh.

2. Abolish the debriefing policy and modify active/inactive gang status criteria. Prisoners are accused of being active or inactive participants of prison gangs using false or highly dubious evidence, and are then sent to longterm isolation (SHU). They can escape these tortuous conditions only if they “debrief,” that is, provide information on gang activity. Debriefing produces false information (wrongly landing other prisoners in SHU, in an endless cycle) and can endanger the lives of debriefing prisoners and their families.

3. Comply with the recommendations of the US Commission on Safety and Abuse in Prisons (2006) regarding an end to longterm solitary confinement. This bipartisan commission specifically recommended to “make segregation a last resort” and “end conditions of isolation.” Yet as of May 18, 2011, California kept 3,259 prisoners in SHUs and hundreds more in Administrative Segregation waiting for a SHU cell to open up. Some prisoners have been kept in isolation for more than thirty years.

4. Provide adequate food. Prisoners report unsanitary conditions and small quantities of food that do not conform to prison regulations. There is no accountability or independent quality control of meals.

5. Expand and provide constructive programs and privileges for indefinite SHU inmates. The hunger strikers are pressing for opportunities “to engage in self-help treatment, education, religious and other productive activities…” Currently these opportunities are routinely denied, even if the prisoners want to pay for correspondence courses themselves. Examples of privileges the prisoners want are: one phone call per week, and permission to have sweatsuits and watch caps. (Often warm clothing is denied, though the cells and exercise cage can be bitterly cold.) All of the privileges mentioned in the demands are already allowed at other SuperMax prisons (in the federal prison system and other states).

You can download full text document of the demands here.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Sign the petition.

Involvement in the July 13th Mass Mobilization!

Plan a solidarity action!

Follow! On Twitter and on Facebook

Use your imagination and your skills; talk to your family and friends about it, and maybe provide them with a handful of shocking facts about the psychological torture that is solitary ? (See below)

Don’t get despondent, get angry.

WHAT IS SOLITARY CONFINEMENT?

In California, nearly 12,000 imprisoned people spend 23 hours-a-day living in a concrete cell smaller than a large bathroom. Across the United states it is conservatively estimated that 20,000 people are in solitary every day. It could be as high as 70,000; it depends on definitions related to time and contact.

In California solitary cells have no windows, no access to fresh air or sunlight. People in solitary confinement exercise an hour a day in a cage the size of a dog run. They are not allowed to make any phone calls to their loved ones. They cannot touch family members who often travel days for a 90 minute visit. They are not allowed to talk to other imprisoned people. They are denied all educational programs, and their reading materials are censored.

UNFATHOMABLE SCALE AND WIDESPREAD USE

“The [psychological and cognitive effects of long term isolation] is not something that’s easy to study, and not something that prison systems are eager to have people look at,” says Craig Haney, psychology professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz, who notes that the widespread use of solitary is a very modern phenomena.

We have an overwhelmingly crowded prison system in which the mandate to rehabilitate and provide activities for prisoners was suspended at the same time as the prison system became overcrowded. Not surprisingly, prison systems faced with this influx of prisoners, and lacking the rewards they once had to manage and control prisoner behavior, turned to the use of punishment. And one big punishment is the threat of long-term solitary confinement. They’ve used it without a lot of forethought to its consequences. That policy needs to be rethought.

Writing for the New Yorker (Hellhole) in 2009, physician Atul Gawande quoted extensively from Haney’s research and added:

After months or years of complete isolation, many prisoners “begin to lose the ability to initiate behavior of any kind—to organize their own lives around activity and purpose. Chronic apathy, lethargy, depression, and despair often result. . . . In extreme cases, prisoners may literally stop behaving” (Haney). [They] become essentially catatonic.

Keep yourself informed; keep progressing; keep honest; follow news on the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity website.

In solidarity, Pete.

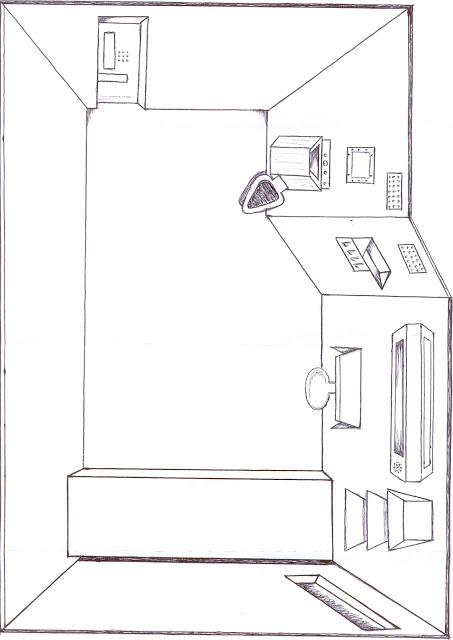

The image above was drawn by Katherine Fontaine, a San Francisco based architect, prison-questioner, friend to all, and book-art-space-collective co-runner.

“There are very few pictures of SHUs. The last drawing that was found at the Freedom Archives in San Francisco was from when Reagan was the Governor of California,” says Fontaine.

With solitary confinement, such a hot news topic, Fontaine was compelled to sketch when she realised there were very few images of solitary cells in circulation.

“I was given the few photos that exist from other similar prisons and a diagram that was used in a previous court case drawn by a prisoner while in an SHU at Pelican Bay. The drawing is what I came up with from the materials I was given,” explains Fontaine who hopes her drawing of a Pelican Bay State Prison Secure Housing Unit (SHU) will be used — in media materials and campaigns — by any organizations protesting solitary confinement.

Fontaine’s commitment to make reliable sketches of prison spaces and apparatus was spurred by a chance encounter with some fellow professionals in an unlikely place. She was among a crowd outside the Central California Women’s Facility protesting overcrowding inside the prison.

Fontaine noticed a person within the crowd with a sign that read ‘Architects Against Overcrowding In Prisons.’ On the back of the sign was www.ADPSR.org. The acronym stands for Architects, Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility. Despite her day job as an architect, ADPSR was not a group with whom she was familiar. Upon reading the statement for the Prison Alternatives Initiative, one of ADPSR’s projects, Fontaine was all-in.

ADPSR state:

“Our prison system is both a devastating moral blight on our society and an overwhelming economic burden on our tax dollars, taking away much needed resources from schools, health care and affordable housing. The prison system is corrupting our society and making us more threatened, rather than protecting us as its proponents claim. It is a system built on fear, racism, and the exploitation of poverty. Our current prison system has no place in a society that aspires to liberty, justice, and equality for all. As architects, we are responsible for one of the most expensive parts of the prison system, the construction of new prison buildings. Almost all of us would rather be using our professional skills to design positive social institutions such as universities or playgrounds, but these institutions lack funding because of spending on prisons. If we would rather design schools and community centers, we must stop building prisons.”

Fontaine’s sketches will regularly appear in Actually People Quarterly, partly to inform as partly as a means to focus her thoughts.

“People need to see them,” she says. “Also it was such a powerful thing for me to draw that SHU cell. I wonder if anyone else can have a similar feeling just by looking at it or if I just feel so changed by it because I drew it. Maybe it is because I’ve spent years of my life drawing, studying, measuring and designing spaces that in actually creating that image I imagined that actual space so much more clearly than I had before? To imagine being an architect and *designing* that space is incomprehensible to me.”

Incidentally, ADPSR was recently featured on the excellent podcast 99% Invisible in an episode called An Architect’s Code, following mainly the activities of Raphael Sperry, ADPSR’s founder.

Below is Fontaine’s sketch of cage used routinely within the California prison system. The cages are sometimes to hold prisoners during transfer between units but, increasingly, used for group *therapy* — an oxymoron if there ever was one.

I’d also like to take this opportunity to share the work of some other determined prison sketchers, some of whom are prisoners.

From the website, Solitary Watch:

One of the most prolific and talented artists in solitary is 60-year-old Thomas Silverstein, who has been in extreme isolation in the federal prison system under a “no human contact” order for going on 30 years. (He describes the experience here.) His artwork appears on this site. It includes meticulously detailed drawings of some of the cells he has occupied, including one pictured below, which is designed (with built-in shower and remote-controlled door to an exercise yard) so that he never has to leave it or encounter anyone at all.

Next is this cell in Ohio, drawn by prisoner Greg Curry.

And finally, Ojore Lutalo has made some of the most politically charged prison art I’ve ever seen. Below, an isolation cell, and very below, Control Units, 1992.

When depicting prisons and their abuses there is no hierarchy of medium; sketches, photos, videos and oral testimony conspire to deliver a fuller picture. I will say though that these narrative rich drawings are more powerful than many photographs I come across.