Leventi, David - Stateville, Joliet, IL

Following my recent post of David Leventi‘s work, a reader contacted me to alert me of the potential (and presumably happenstance) development of Stateville Correctional Center, Joliet, Illinois as an art object.

Consistently through the representations of Stateville is the description of the roundhouse as one of the last remaining prisons in America adhering to the Panopticon model developed by Jeremy Bentham.

Let us be clear, the Panopticon is an outdated and abusive model for corrections; it relies on a small number controlling a large number through the threat of constant supervision. Modern correctional management must look beyond disciplinary techniques based upon spatial arrangement and look toward truly transformative (educational) engagement with prison populations.

Still one can only speculate that the roundhouse prison is of interest to artists primarily because of its “purity” of form as understood – and communicated – through the formal qualities of composition within the photographic print.

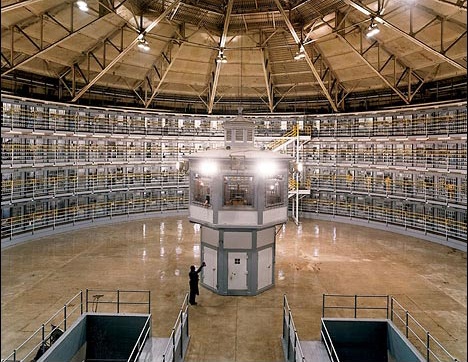

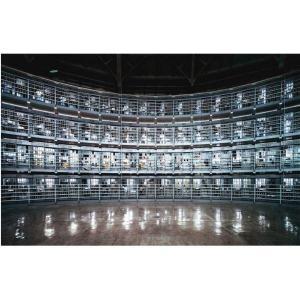

USA. Illinois. 2002. Stateville Prison. F house. There were originally four circular cell houses radiating around a central mess hall. The buildings were based on Jeremy Bentham's 1787 design for the panopticon prison house. The first round house was completed in 1919, the other three were finished in 1927. F house is the last remaining panopticon cell house. It's used for segregating inmates from the general prison population and for holding inmates who are awaiting trial or transfer. -Doug DuBois & Jim Goldberg.

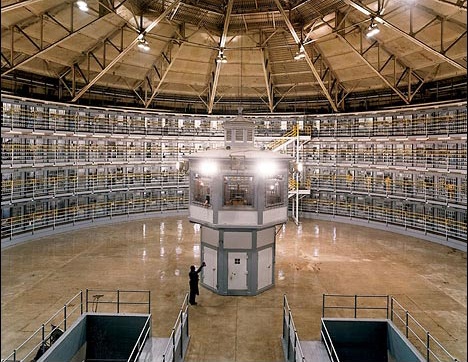

In 2002, Doug Dubois, along with Jim Goldberg, went to Stateville Correctional Centre, and took a picture (above) of the prison’s interior. The New York Times later published the photograph.

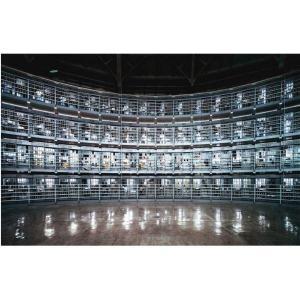

A while later, Dubois found out that Andreas Gursky had too gone to Stateville, apparently inspired by Doug and Jim’s photograph and took a picture himself (below). Gursky has admitted in his career he finds ideas for images in newspapers and other popular media. Gursky’s image put in context here, at the Brooklyn Rail.

Andreas Gursky, “Stateville, Illinois” (2002), C-print mounted on Plexiglas in artist’s frame. Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

So, this raises questions. Has Stateville prison inadvertently become a tease, and a subject for curious photographic artists?

Do the individual activities of artists have a bearing on one another? Should these images exist within the same discourse? Do photographic attentions of the 21st century have any relation to the need and stresses of current correctional politics in Illinois?

Does the ascendancy of Stateville onto gallery walls effect any significant – or measurable – impression of Stateville prison within public consciousness?

Or are Dubois, Goldberg, Gursky and Leventi just continuing an intrigue which has continued throughout the decades?

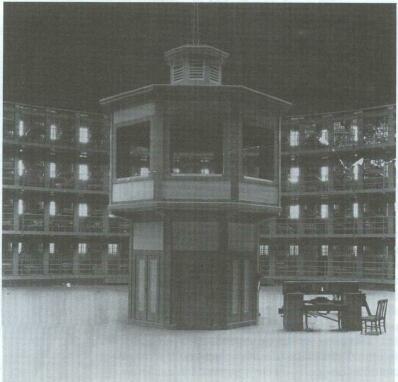

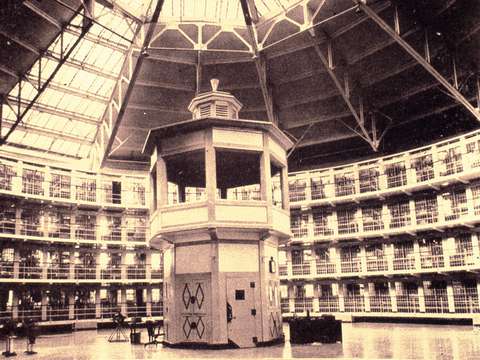

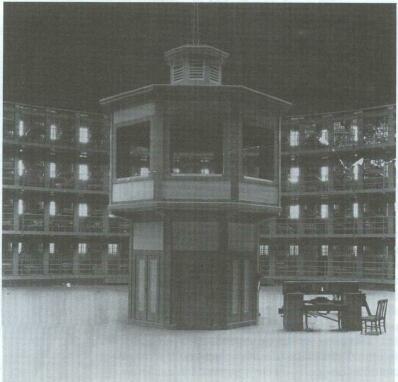

Postcard: Stateville Penitentiary, near Joliet, Illinois (ca. 1930s).

Postcard of an American panopticon: "Interior view of cell house, new Illinois State Penitentiary at Stateville, near Joliet, Ill." Source: Scanned from the postcard collection of Alex Wellerstein. (Copyright expired.)

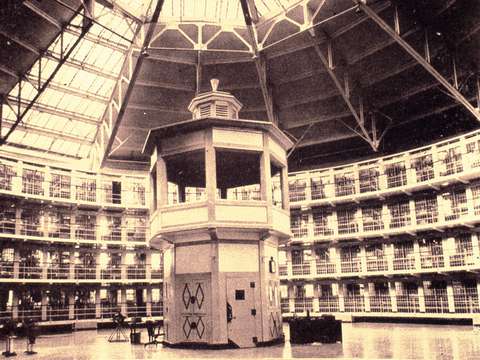

Photo of guard tower in round house at Stateville. Courtesy of Illinois State Historical Library. The second state prison was authorized at Joliet in 1857. It was built by convict laborers. That 135-year-old Joliet prison still houses more than 1,100 inmates. Meanwhile, Stateville. prison, also in the Joliet area, opened for business in 1917.

Inmates at Stateville Penitentiary in 1957. (Sun-Times News Group file photo)

Prison guard in a security tower, Stateville Penitentiary, Joliet, Illinois, USA. © Underwood Photo Archives / SuperStock

Panoptic guard tower at Stateville Prison, Stateville Prison (US Bureau of Prisons, 1949, p. 70), 1940s