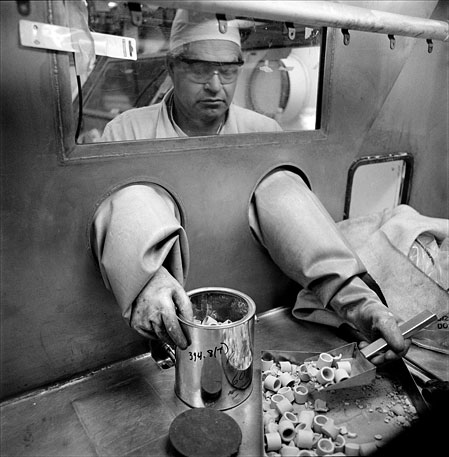

Nuclear Residues Repacking Glovebox, Building 440, Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, 2002. © A.W. Thompson

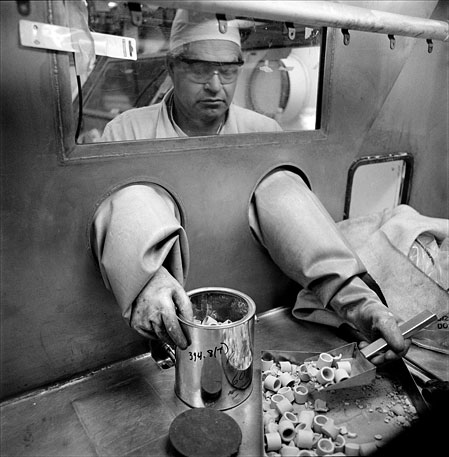

A.W. Thompson‘s largest single project, “Incendiary Iconography” addresses Cold War-era nuclear sites in the United States that are in the process of public reclamation and/or transformation under the Defense Environmental Restoration Program.

The Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant sat at the foot of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains overlooking the high plains of eastern Colorado. Boulder is ten miles to the north, Denver’s two million residents just 16 miles downwind and downstream to the east. The plant operated from 1952 to 1992, and since then the suburbs of Denver have extended to the border of what was a 25 square mile top-secret facility.

Thompson says, “The plant produced plutonium “pits,” for the nation’s nuclear weapons stockpile. A pit, or primary, is a plutonium fission bomb like the one dropped on Nagasaki, and is used to start the fusion reaction in a hydrogen bomb which has over 1000 times the power of a fission bomb. Plutonium is a man-made element which is highly toxic in addition to being radioactive.”

On June 6th, 1989, as part of an investigation into allegations of environmental crimes the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Energy’s Office of Inspector General raided The Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant. The raid led to the eventual decision to tear down Rocky Flats.

Again, Thompson, “In 1995 the U.S. Department of Energy labeled Rocky Flats the most dangerous weapons plant in the nation because of the health and safety risks it posed to the plant workers and the surrounding area. Although the search warrant documents were released in 1989, the full text of the grand jury investigation and findings remains sealed, despite efforts by members of the gagged grand jury to make them public. The former Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant site was officially designated a National Wildlife Refuge with the completion of decontamination and deconstruction activities in October 2005. The wildlife designation was chosen because it afforded the lowest level of cleanup standards. Debate continues among former workers and local citizens about the adequacy of the cleanup.”

“Rocky Flats was the only nuclear pit facility in the U.S. The Department of Energy announced plans to develop a new hydrogen bomb on March 2, 2007. Site location for a new multi-billion dollar pit facility is currently underway without significant public debate about the need, or the long-term financial, environmental, and security costs of a revived nuclear weapons production program, which many believe, will start a new nuclear arms race.”

Characterizing Legacy Residues in Plutonium Building 771, Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant, 2001. © A.W.Thompson

BIOGRAPHY

Thompson (born in Colorado) is the Director of the School of Communications and an Associate Professor of Photography and Visual/Media studies at Grand Valley State University, Michigan. He earned his B.S. in Physics from the University of Dallas and his M.F.A. in Photography from Washington University in Saint Louis.

Thompson has lived and worked in Rome, Italy and across the Midwest as a freelance and commercial advertising photographer. His work is about “the meanings attributed to, or derived from, experiences of place and/or technology, and the relationship of art and science as ways of knowing.”