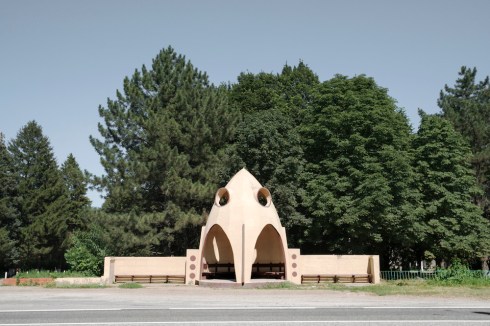

It’s unmistakable. That gazebo. That hexagonal cover to that picnic table. One needn’t notice the flowers, or even the poster, to the memory of Tamir Rice to recognize this utility structure as that under which the 12-year-old was murdered by Cleveland police. Even the bollards between us the viewer and the polygon shelter seem instantly familiar. For it was between those bollards and the gazebo that the cop car screeched to a halt, it’s door flew open and the first emerging officer shot Tamir dead. In the blink of an eye.

Tamir Rice was shot twice from less than 10 feet.

Back in 2014, as I watched the footage of Tamir Rice’s murder, I wondered then, why did the the cops mount the curb? Why did they bypass the pavement and careen the patrol car onto the grass? Into the park? Why the frantic invasion of a place for play and recreation? Why, given the clear lines of sight (evident both in this photo and in the murder footage) from a good distance away, did they not approach slowly and with caution?

“This court is still thunderstruck by how quickly this event turned deadly,” wrote Ronald B. Adrine, Cleveland Municipal Court Administrative and Presiding Judge in an Administrative Order on the case. “On the video, the zone car containing Patrol Officers Loehmann and Garmback is still in the process of stopping when Rice is shot.”

Misinterpreting a situation and mistaking a toy for a gun (in the case of Tamir Rice) — or mistaking anything handheld, or any motion toward a hip or a pocket (in the cases of thousands of others) — is the defense to which law enforcement turns repeatedly and, calamitously, the one which almost always exonerates them of their crimes.

This is a photo made by Alanna Styer. It is part of the project Where It Happened for which Styer visited and photographed 54 sites where people of color were slain at hands of law enforcement. In 2016, The Guardian reports, 1,093 people were killed by police officers in the United States.

“That is an average of three people a day,” writes Styer. “The incidents detailed in my archive span 50 years, from 1965 to 2015. This book documents only 54 of the tens of thousands of deaths that have happened over those 50 years.”

Mostly, the locations and details of those thousands of deaths aren’t known beyond the memory of friends and family, the accounts of the cops involved, and the reach of an investigation … if one occurred. Even then, the details remain contested. The majority of the places in Where It Happened are new to us, the audience. But Styer’s photo of the gazebo at Cudell Recreation Center is not new. It’s power rests, for me, in the fact that I have previous familiarity with the place through the news coverage and activism in the aftermath of Rice’s murder. I recognize the site. You probably do to. We might also recognize the site of Michael Brown’s death on that tarmac road with verges of short, thinning grass. We may recognize other sites of avoidable killings that made it to our news feeds and memory. We don’t, regrettably, recognize the vast majority of the tragic theaters to which Styer’s work speaks. There are too many.

Styer’s photo shifts our vantage point from the elevated view of the CCTV across the street and down to street level. Whereas previously the benches and the posts were rendered in the indistinguishable and out of focus action of the footage, they’re now brought into sharp focus. We see the underside of the gazebo roof, not the top. We’re provided a perspective from the asphalt where the cop car could have and should have been.

Being “in” this image, I only want to get out, of course. A world in which this wasn’t a murder site and you or I didn’t recognize it as such would be, inarguably, a better world. Specifically, I want to step back. The unnecessary haste with which officers Timothy Loehmann and Frank Garmback charged into this scene gloms onto this image. That unfathomable CCTV footage is this photo’s frame.

Loehmann and Garmback’s excessive urgency which escalated the event from zero to murder perverts Styer’s image. But it also makes it. This photo works upon and within the collective exposure we’ve had to that grainy footage. Styer’s tribute here isn’t working in isolation but in extension of previous visual feeds to which we’ve all been audience. This image is an intervention and it works to disrupt our (possibly passive) consumption of death. It revisits the space and time of an event in which Tamir Rice had, essentially, no agency. The stillness is terrifying. True, the image could be read simply as a visual description of a memorial but I argue that precisely because it grounds us between the CCTV camera and Rice’s swift execution, the photo re-activates both the event and our relation to it.

Acts of police brutality (or citizen brutality, e.g. George Zimmerman against Trayvon Martin) frequently spurn a battle of images — calls for the immediate release of dash cam footage; calls for body-cams; different photos are circulated and cast as sympathetic, or not, to the victim and the perpetrator; media outlets trawl the social media feeds of victims, perpetrators and associated individuals. Whether conscious or not, Styer is reacting to such frenzies. She is paying homage to the victims, months or years after the news story has passed and the casket lowered. Where It Happened is a dark type of pilgrimage but I feel Styer is making it in good faith and I argue she’s returning with images that are a positive contribution. Google Street View does not make imagery that is conscious or respectful (interestingly, it hovers above street level like CCTV, delivering a detached record). Cellphone images may carry as much, if not more, respect as Styer’s photographs and this might be based on a personal connection to the victim, but those amateur images are not made by an artists intent on publicly disseminating them and talking about the issues that forged them.

I admire and have reported on Josh Begley’s project Officer Involved which uses code to automatically render both satellite and Street View images of sites of deaths involving law enforcement. Thousands of sites. While the subject is the same Styer’s work is considerably different in tone and effect. If Begley manages to remind us of the scale of the problem then Styer’s work reminds us to recognize each depressing part of the problem. I can’t code or manipulate Google Maps API but I can walk, bike or drive to killing sites within my own city. Styer’s practice takes time and effort, away from the screen. In 2015, Teju Cole reflected upon the problem of the constant visibility of death. In Death In The Browser Tab, Cole recounts his discomfort with only *knowing* the death of Walter Scott through the infamous footage made by passerby Feidin Santana who was hiding in the bushes. Cole had the opportunity to visit North Charleston and with a friend he found the parking lot of Advance Auto Parts on Remount Road in which Officer Michael Slager first stopped Scott. Then Cole traced the steps of them both to the park in which Scott was slain.

“[…] being there also revealed, in the negative, the peculiarities of the video,” writes Cole, “peculiarities common to many videos of this kind: the combination of a passive affect and the subjective gaze, irregular lighting and poor sound, the amateur videographer’s unsteady grip and off-camera swearing. Taken by one person (or a single, fixed camera) from one point of view, these videos establish the parameters of any subsequent spectatorship of the event. The information they present is, even when shocking, necessarily incomplete. They [videos] mediate, and being on the lot helped me remove that filter of mediation somewhat.”

Styer’s practice is one response to the problematic mediation that Cole describes. Few of us can identify the problem, let alone respond to it. And just as Cole felt better for mindfully visiting the site of Walter Scott’s death, and just as Styer was compelled to visit 54 catastrophic sites, we can choose to seek out a different image. Away from local TV news and social media, death might become less abstract? The sheer scale of the issue might become overwhelming. It is. But are we citizens that feel or do we just talk about what it is to feel?

Are we inured and numbed by murder on our screens? Or are we compelled to act because of it? We can all easily research the institutional violence in our communities. Maybe some of us might be compelled to make pilgrimages of our own and to carve out time to think about the violence that always plays out on our streets before it is broadcasted into our homes. Styer took the time and she has mediated at these sites. Her image of the gazebo in which Tamir Rice was shot and killed gave me the opportunity to mediate. I am grateful for that.

Sometimes photographs are about what’s literally depicted. Sometimes the lessons in photographs are in the method by which they were made. In Where It Happened it is both.

–

Alanna Styer is currently crowdfunding a book of images from her series Where It Happened. Please consider supporting the production of the photobook, titled No Officers Were Injured In This Incident, by visiting Styer’s Kickstarter page.

Listen to a radio interview with Styer about the project and her goals for the book.

The Young New Yorkers (YNY) uses art to help children imagine different lives for themselves, to conjure new possibilities for their neighbourhoods and to interrogate what community justice is and might be.

The Young New Yorkers (YNY) uses art to help children imagine different lives for themselves, to conjure new possibilities for their neighbourhoods and to interrogate what community justice is and might be.