You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘California’ tag.

Nicely said:

It was disheartening to read Justice Scalia, in his dissent, describe the case as one “whose proper outcome is so clearly indicated by tradition and common sense, that the decision ought to be shaped by the law, rather than vice versa.”

Justice Scalia’s respect for the requirements of the law apparently stops when convicted felons are the litigants. While he calls for common sense, he ignores the expert testimony, which led to the finding that prisoner release was necessary. He implies that 46,000 prisoners will be released en masse, and indiscriminately. At the time the opinion was issued, the prison population had already undergone a reduction of 9,000 inmates.

The reality is that the releases will not be en masse and the figure will be much lower. Relatively few prisoners serve their entire sentences due to the availability of good-time credits, which provide for reduction in the time served. The state has great discretion to select those inmates whose early release presents a minimal risk to public safety. Many of those prisoners who are serving time for technical parole violations will be diverted to community-based programs.

Justice Scalia also claims, without proof, that “Most of them will not be prisoners with medical conditions or severe mental illness; and many will undoubtedly be fine physical specimens who have developed intimidating muscles pumping iron in the prison gym.”

Justice Scalia ignores the reality that gyms have been used to house prisoners for many years, which is part of the problem brought on by overcrowding. Overcrowding and lockdowns compromise the immune systems of prisoners due to a lack of fresh air and exercise. The lack of sanitary conditions in these gyms exacerbates the spread of disease. Weights have not been available in California prisons for more than a decade.

While Justice Scalia’s criticism of the majority decision is trenchant and beautifully written, it is based on a false notion of the conditions in prison and blindness to the consequences of subjecting men to inhumane treatment for more than a decade. Justice Scalia ignores the sad reality that many of those who suffer from mental or physical disabilities lack the ability or means to bring complaints to federal court, especially given the difficult obstacles placed by Congress and the Court to prisoner lawsuits in recent years.

via zunguzungu

UPDATE: 06/27/2012 – The Prison Law Office (PLO), Berkeley represented the prisoners of California. PLO pointed me in the direction of this full gallery of images that were available to defense and prosecution teams.

On May 23rd, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) affirmed – with a 5-4 majority – a federal court order requiring California to reduce its prison population to 137.5% of design capacity. California has two years to shrink the number of prisoners by more than 33,000. California currently has 143,335 prisoners, which is still significantly less than the 166,000+ the state housed at its peak five years ago.

Brown vs. Plata (formerly Schwarzenegger vs. Plata) was a landmark case in U.S. legal history and, I would hesitate a guess, the largest release program of convicted individuals ever enacted. And it is the right decision.

You can download the full SCOTUS decision as well as other documents from the case at SCOTUSblog.

I want to draw attention to one particular aspect of the ruling: Justice Kennedy’s inclusion of photographs in the appendix.

Justice Kennedy wrote for the majority, joined by justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan. Justice Scalia wrote a dissent joined by Justice Thomas, and Justice Alito wrote a dissent joined by Chief Justice Roberts.

Two of the photographs Kennedy included show prisoners being housed in a gymnasium. These are open dorms and clearly unsuitable for such numbers. The lawsuit however, was centred on standards of medical care; it was stresses of overcrowding that led to the drop in healthcare standards to the point of “cruel and unusual punishment” and the associated violation of the Eighth Amendment.

Justice Kennedy in a sincere way was trying to illustrate a point. An editorial at The New York Times is on board:

Looking at the photos, there should be no doubt that the conditions violate the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

That’s a bit prescriptive for me but I’ll forgo that.

The images are quite unremarkable inasmuch as they are the norm. News media has shown images from California prisons like these for years. So much so, the California Department of Corrections provided a gallery of official “Prison Overcrowding Photos” (now with added fisheye lens!)

In 2006, Max Whittaker photographed overcrowded gymnasiums at Folsom prison. In 2007, Justin Sullivan went to Mule Creek State Prison. After the verdict, Gary Friedman‘s photo gallery ran in the LA Times.

The third picture (below) shows something a little different. It depicts the apparatus of inadequate care. According to the Court’s opinion: ‘Prisoners in California with serious mental illness do not receive minimal, adequate care. Because of a shortage of treatment beds, suicidal inmates may be held for prolonged periods in telephone-booth sized cages without toilets. A psychiatric expert reported observing an inmate who had been held in such a cage for nearly 24 hours, standing in a pool of his own urine, unresponsive and nearly catatonic. Prison officials explained they had “‘no place to put him.’”

It’s impossible to say what sort of reaction publication and underlining of these three images means for anyone reading-up on the case. Dahlia Lithwick for Slate asks Do photographs of California’s overcrowded prisons belong in a Supreme Court decision about those prisons?:

“Whether those photos will change anyone’s mind about the morality of prison overcrowding is open to debate. Whether they should may be the more important, and more interesting, question.” Lithwick wonders, “Should the court be using visual aids to prompt emotional responses or be inviting citizen fact-finding in the first place?” The weakness of this question is in its presumption that it is only through an emotional reaction that a viewer will conclude make-shift open dormitories and cages are unacceptable. Surely, logic dictates that these are not beneficial management strategies, let alone conducive to rehabilitation.

Photographs of overcrowded prisons in California have been available for a long time for anyone who cared to search. These three are representative of the failed system, and quite honesty Kennedy had thousands to choose from.

For a full round up of the ruling visit the phenomenal Prison Law Blog.

UPDATED: 06.12.2011

Previously, I was under the impression that only three photographs were used in the Brown vs. Plata deliberations, but according to Mother Jones, the two images below were also items of the appendix.

Scar © Sye Williams

Sye Wiliams photographed in Valley State Prison for Women, Chowchilla, California. His portfolio was included in the June 2002 COLORS Magazine.

Williams’ entire Women’s Prison portfolio can be seen on his website.

It is a bit of a time machine without a specific destination. The images are prior to 2002, we know that much. But it is anyone’s guess which particular year. (I have asked Sye and will update with the answer.)

Williams’ choice of film-stock, the era-less prison issue coats and baseball t-shirts, all amount to a almost “date-less” space and time. Even the hairstyles span any number of decades. Yet, this is what prison is for many inmates; prison is a time of stasis, if not reversal. When time is not your own, how should it matter? And when one’s time is detached (in an experiential way) from that of dominant society, then it stands to reason that very different rules of judging the days, measuring value, gauging worth, choosing behaviour, and – dare I say it – opting for styles, would shift significantly.

Officer © Sye Williams

It is not often prison photographers take portraits of correctional officers (mostly down to legal reasons).

Williams’ Officer (above) is a slippery image. The officer maintains the same steeled look as some of the inmates. The fact that she wears a helmet with visor, and that this particular portrait exists within a portfolio of weapon-still-lifes and an photograph depicting model-hairdresser-heads all unnerves me a little.

It is not that women’s prisons are uncontrollably violent. To the contrary, they’re more likely sites of boredom. However, as a viewer to Williams’ work, I find myself adopting the same caution as the staff and administration. Prisons are places where daily activities are shaped by the need to always prepare for the worst case scenario.

Williams manages to subtly suggest the latent violence of prison, and given recent reports (California Women Prisons: Inmates Face Sexual Abuse, Lack Of Medical Care And Unsanitary Conditions) he is probably close to the truth. Apparently, Valley State Prison for Women in Chowchilla is less dangerous than it once was, but it remains a notorious prison for women.

In the deviant milieu of prison, even when time ceases to exist, vigilance necessarily remains a constant.

View Sye Williams’ entire Women’s Prison portfolio.

Beauty School © Sye Williams

Ara Oshagan sat down for an interview with Boy With Grenade to talk about his project Juvies from the California Youth Detention system. Oshagan talks about “access, his process and the state of documentary photography today.” It’s long but parts make good reading.

“There is a certain pragmatism in my outlook. I knew I could not have access to these kids outside of the limited access that I had when I went in. So I did not worry about that. I made sure that I was totally ready—physically and mentally—when I did spend time with them, to make the absolute most of that time, to be fully in the “space” with them, to have a clear mind, to connect as much as possible, and hope that this connectivity will translate into good photographs.”

“To make good photographs, I feel, one must create a good process. Photographs can never be an end; they necessarily must be a byproduct of an experience, a process. That connectivity with your subject matter must be present. If you go into a situation with the sole purpose of making “good photographs” you will invariably fail. Or at least, I will.”

Read the full interview.

I’ve written about Oshagan’s Juvies on Prison Photography once previously.

Book cover: Maggots in My Sweet Potatoes

In the early 1990s, photographer Susan Madden Lankford rented an old San Diego jail for commercial photography. She soon attracted the interest of the homeless in the area, who before long they began to befriend her, trust her intentions and to tell her about their world. She was making a living as a successful studio photographer but was not fulfilled.

“My life and my photography were full of plastic portraiture. Images of individuals wanting the ‘right image’ and not the one with real expression and life.”

She soon embarked on a three publication project looking at the underclass of her home city. downTown U.S.A.: A Personal Journey with the Homeless was her first book, soon followed by Maggots in My Sweet Potatoes about the incarceration of women and children. Lankford is soon to release a documentary film about the criminal justice system.

Inmate Behind Chain Link Fence. Las Colinas Detention Facility for Women in Santee, California. Photo by Susan Madden Lankford. Taken from the book, “Maggots in My Sweet Potatoes: Women Doing Time,” by Susan Madden Lankford, Humane Exposures Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted with permission.

The “Safety Cell” Used for Solitary Confinement. Las Colinas Detention Facility for Women in Santee, California. Photo by Susan Madden Lankford. Taken from the book, “Maggots in My Sweet Potatoes: Women Doing Time,” by Susan Madden Lankford, Humane Exposures Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted with permission.

This Is My Family. Las Colinas Detention Facility for Women in Santee, California. Photo by Susan Madden Lankford. Taken from the book, “Maggots in My Sweet Potatoes: Women Doing Time,” by Susan Madden Lankford, Humane Exposures Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted with permission.

BIOGRAPHY

Lankford studied with Ansel Adams and is a graduate of the Brooks Institute in San Diego. Maggots in My Sweet Potatoes won the following awards: Publishers Weekly – Best Books of the Year, Web Pick of the Week; ForeWord Magazine – Book of the Year, Silver Award – Social Science; ForeWord Magazine – Book of the Year, Bronze Award – Women’s Issues; Independent Publisher Book Awards – Gold Medal, Women’s Issues; 2008 DIY Book Festival – Grand Prize Best Book of the Year; 2009 Eric Hoffer Book Awards – Grand Prize. Lankford’s work is the basis for the new film, It’s More Expensive to Do Nothing releasing this fall 2010.

More on Lankford from the San Diego Union-Tribune here.

Five-part lecture given by Lankford can be viewed. First part here.

You can find out more about her projects at Humane Exposures and get updates on the Humane Exposures Blog.

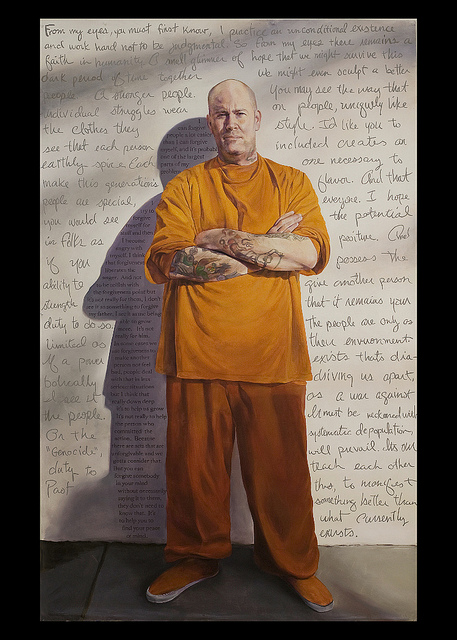

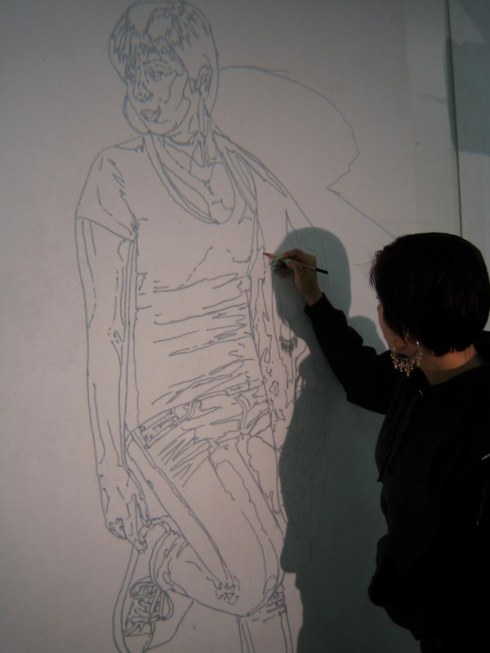

© Evan Bissell

Artist Evan Bissell brought together a group of teens who had not known each other previously, but shared a common circumstance; they were children of men incarcerated at San Francisco County Jail.

The project, What Cannot Be Taken Away: Families and Prisons Project, spanned 9 months.

Bissell and the teens shared writings and audio to establish themes for their work. Later they would visit family in SF County Jail and take photographic portraits to work from. Eventual they mounted a show at SOMArts in San Francisco.

I am a little unsure as to the ultimate claim the students have on the final product. Evidently, they decided the elements and the design, but every piece is finished with the polished painting skills of Bissell’s brush. But of course, it wasn’t only these large portraits on view; exploratory/experiential paintings of the students were displayed and the centre-piece of the show was an installation piece.

Despite the apparent dominance by Bissell over the final product, the intangibles of the collaborative project – including but not limited to discussion, new ideas, “healing & justice”, friendship, self esteem – far outweigh a critic’s (my) reserve.

I highly recommend you download the PDF time-line; it offers an impression of the shared politics of the project. Also the process describes the engagement between teacher and student.

PHOTOGRAPHY?

The tie in comes from a quote by Bissell, “I was unfortunately not allowed to photograph our workshops in the jail, so all of the pictures come from our meetings with the youth.”

© Evan Bissell

© Evan Bissell

© Evan Bissell

© Evan Bissell

© SOMArts

© SOMArts

What Cannot Be Taken Away: Families and Prisons Project. Closing September 19th 12:00-2:00 at SOMArts – 934 Brannan St. in San Francisco (at 8th Street).

All images from Bissell’s WCBTA website and SOMArts Flickr.

Frozen Lake & Cliffs, Kaweah Gap, Sierra Nevada, California, 1932 © Ansel Adams

A couple of months ago I went to Sequoia National Park. Our itinerary was grueling and didn’t help when we took the wrong mountain pass on the penultimate adding 30 miles to our trip. Twice (in and out) we went over Kaweah Gap.

I saw the Ansel Adams image above somewhere else recently but it was without a caption. It looked a lot lie Kaweah Gap but then again a lot of Sierra Nevada lakes look rather spectacular. Anyway, I was glad Doug Stockdale offered a caption and its location.

Whichever way the Ansel Adams/Uncle Earl saga plays out (they’re having a joint show now!) I just wanted to say it is not easy to lug any weight, including heavy camera equipment up to 12,000 feet. They are both as fit as pack horses.

Joel at Frozen Lake & Cliffs, Kaweah Gap, Sierra Nevada, California, 2010 © Pete Brook

This is worrying.

Los Angeles Jail guards at the Pitchess Detention Center, Castiac, CA have a new weapon in their armory. The 7 1/2-foot-tall ‘Assault Intervention Device’ emits an invisible 5-inch-square beam that causes an “unbearable sensation”.

The device is manufactured by Raytheon, an 80 year old multibillion dollar surveillance, radar and missile specialist with a catalogue of space-war technologies. Compared to Raytheon’s sprawling, global and stratospheric innovations, the ‘Assault Intervention Device’ is small, contained and personal.

Cmdr. Bob Osborne of the LA County Sheriff’s Technology Exploration Program, one of several deputies who tested (see video) the ‘Assault Intervention Device’, described the experience, “I equate it to opening an oven door and feeling that blast of hot air, except instead of being all over me, it’s more focused.”

The device – controlled by a joystick & computer monitor and with a 100 foot range – will be mounted near the ceiling in a unit at Pitchess housing about 65 inmates.

NBC Los Angeles reports, “The energy traveling at the speed of light penetrates the skin up to 1/64 of an inch deep. […] ‘Assault Intervention Device’ is being evaluated for a period of six months by the National Institute of Justice for use in jails nationwide.”

The statistics for violence at Pitchess are quite shocking – 257 inmate-on-inmate assaults occurred in the first half of the 2010.

Pitchess, a facility with 3,700 inmates, is a large facility with riots (some very recently) and obviously needs to counter the culture of violence. I just wonder whether shooting brawling inmates with lasers is the right way to go about it?

– – –

I have looked at highly sophisticated technologies before and how their imaging can affect our understanding of prison life, tension, engagement.

How would images of prisoners reeling from a ‘Assault Intervention Device’ laserbeam influence public opinion about this new fan-dangled correctional management tool? The deputies who’ve tested it say it’s unbearable and can only be endured for three seconds maximum, yet everyone knows that tasers are often repeatedly discharged upon stubborn, adrenaline-fuelled (sometimes drugged up) targets.

Again, very worrying.