You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Jail’ tag.

Reading the Goethe-Institut Fashion Scene article about Haeftling designers in Berlin, I thought it was an Onion style send up. “Prisoner chic” sounds like something straight out of satire, but I guess I was snoozing when this hit the news wires in 2003.

Haeftling (translated as ‘Prisoner’) employs inmates across Europe to manufacture clothing and housewares inspired (they say) by prison life, “The garments are highly functional and have a classic and timeless cut. Only high-grade, rugged fabrics are used in manufacturing.”

Well, whatever you say. I actually don’t mind how they market it, I am just pleased they support prison reform, the abolition of the death penalty, political prisoners rights and a philosophy of rehabilitative justice.

Haeftling Tray

But let’s not kid ourselves. This project was borne of commercial interests. “It began in the JVA (Justizvollzugsanstalt/prison) Tegel and developed into an international undertaking. More and more prisons have joined and today production is even taking place elsewhere in Europe. One Bavarian prison supplies honey from its own two colonies of bees; a prison in Switzerland even has its own vineyard and exports its own red (Pinot Noir) and white wine (Müller Turgau).” (source)

Karola Schoewe, Haeftling’s PR & communications manager says, “On the whole, the prisons are all very helpful,” says “There are some prisons that have very good production capacities for making homeware.”

Schoewe then marries the business speak to social responsibility speak, “Through its production, Haeftling is creating measures that help to support rehabilitation processes.”

Haeftling Espresso

Without seeing Haeftling’s account-books or sitting in on a board meeting, I have no way to tell if resources and profits are divvied up in a way that benefits prisoners more then in the state run prison industries. This was the situation in July 2003

(Author’s Note: €12.50 is substantial pay compared to American prisons.)

Prison industries are a divisive issue. For some they are the perfect use of prisoners’ time and energies developing job skills, work community & self-esteem. To others prison industries are a modern slave labor exploiting societies’ self-created incarcerated class.

Both viewpoints have legitimacy, but the first makes a prior assumption that could be misleading – that work programs are the only means to provide skills, community or self-worth. Education does this too.

But educating someone instead of putting them to work is going to cost a prison authority rather than generate it wealth.

Generally, I am unnerved by the disconnect between the reality of incarceration and its representation to consumers,

Then again, Klaus-Dieter Blank, of Berlin’s Tegel Prison states the success of the label’s online store has meant that people are beginning to understand “what goes on behind the walls”. Haeftling features on the Tegel Prison website.

Is there too much space here for consumers to create their own version of prison life? What is included and/or played down in the minds of consumers? Are they being coerced and sold a disingenuous view along with that ‘rugged’ product?

"Justiz 82" Scratchy Blanket. Haeftling Product

We can assess this a number of ways – rehabilitative worth, public awareness worth, benefits to state finances, tax-payer savings, external benefits of development in social entrepreneurship.

But essentially, we must ask, “Does this enterprise help reduce prison populations by reducing recidivism? It MUST be compared to other rehabilitative programs. The purpose of prisons the world over should be to create societies where prisons are no longer necessary.

How do you judge this type of enterprise?

Prison Chess Portrait #14. Oliver Fluck

Oliver Fluck’s series of Prisoner Chess Portraits is an interesting counterpoint to other prisoner portraiture. It is unfussy, neutral, quiet. Fluck is experimenting with the figure and I would like to see him in the future settle with a preferred vantage point in relation to his sitter. For example, I like the portraits of the Prison Chess Champ and of Christopher Serrone. Fluck is headed in the right direction.

Prison Chess Portrait #14 (above) is a very strong shot also taking advantage of particularly high contrast light conditions.

Is photographing stationary silent chess-playing sitters simple or difficult? On the one hand, the sitter is still for you, but on the other, it’s difficult to spark rapport with a man concentrating on the game.

Text with Image

An integral part of the project is Fluck’s drafted questionnaire which secured answers to standard questions from as many competitors as possible.

Inmate quotes such as, “Having been incarcerated since age 15 and never getting out, it is helpful and healthy to know that not all of society lacks interest or willingness to become productively involved” keep reality checked. As do sobering statistics such as 50+ years or 66-year prison-terms.

J. Zhu. Oliver Fluck

Christopher Serrone. Oliver Fluck

Prison Chess Champ. Oliver Fluck

Q&A with Oliver Fluck

How and why you came to this topic?

I enjoy playing chess, which is why I’m in touch with the local university chess club here in Princeton. The students got the opportunity to play against inmates of a maximum security prison, and when I heard about it, I proposed to photograph the event and volunteer as a driver for the students.

What are your hopes for the project as a whole?

Very frankly, from a photographer’s point of view, I would like to see it exhibited, and provoke some thought.

What is your message with the portraits?

I can talk about one thing that I am not trying to do: I’m not trying to propagate any kind of standpoint about how one should deal with criminals, and whether or not they should have the right to enjoy chess. I’m like most other viewers, I stumbled upon this project and got curious … Curious on an unprejudiced level from human to human. Start from there if you are looking for a message.

Anything else that you’d like to add and feel is important.

I would like to thank John Marshall for this experience, and David Wang for constructive feedback regarding the prisoner questionnaire.

Competitor with Unknown Name. Oliver Fluck

Prison Chess Portrait #4. Oliver Fluck

Prison Chess Portrait # 21. Oliver Fluck

Original Links to portraits 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Oliver Fluck’s Flickr

Watch this youtube clip of a local news report from the prison during the tournament.

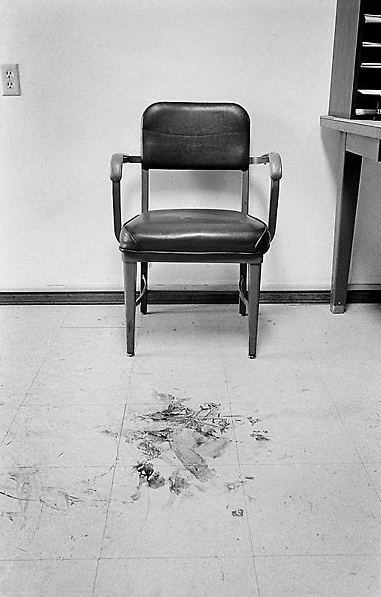

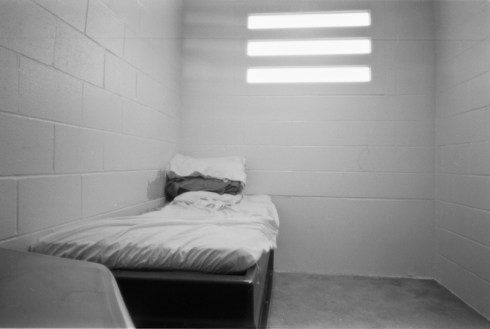

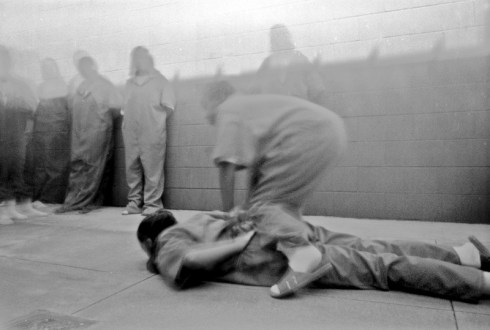

These images are the result of a collaboration between photographer Steve Davis and the girls of Remann Hall Juvenile Detention Center, Tacoma, Washington State in the US.

Davis was forced to think of the camera as a tool for different ends, essentially rehabilitative ends. For legal reasons and the protection of minors, Davis and his female students were not allowed to photograph each others faces. It became an exercise in performance as much as photography.

We see portraits of the girls with plaster masks, heads in their hands. The girls limbs outstretched made use of evasive gesture. The long exposures of pinhole photography resulted in conveniently blurred results.

PINHOLE PHOTOGRAPHY vs ROTE DOCUMENTARY MOTIFS

Photography in sites of incarceration often depicts amorphous, vanishing forms within stark cubes; it is usually black & white, and often from peep-hole or serving-hatch vantage points. When this vocabulary is used and repeated by photojournalists, visual fatigue follows fast.

Heterogeneous architecture doesn’t help the documentary photographer. Limited and repetitious visual cues make it tough to work in prisons. Images, shot through doors, by visitors only on cell-wings by special permission, are dislocating and sad indictments of systems that fail the majority of wards in their custody.

I celebrate all photography shining a light on the inequities of prison life. Having said that, very occasionally – only very occasionally, do I wish a “prison photographer” had expanded, waited or edited a prison photography project a little longer … but I do wish it.

Photojournalism & documentary photography have taken a battering from within and been asked some serious reflective questions. I don’t want to accuse photographers of complacency. To the contrary, my complaints are aimed at prison systems that so rarely allow the camera and photographer to engage with daily life of the institution.

Therefore, I stake two positions on the issue of motif/cliché. First, repeated clichés have developed in the practice of photography in prisons. Second, prison populations have had little or nothing to do with the creation, continuation or reading of these clichés.

As a general criticism, I would say photographers in prisons struggle to achieve original work. But, prisoner-photographers – whose experience differs vastly from pro-photographers, custodians and visitors – cannot be held to that same criticism.

WHEN THE PRISONER CONTROLS THE CAMERA

These images by the girls at Remann Hall are distinguished from the majority of prison documentary photography, because the inmate is holding the camera. When an inmate repeats a motif it is not a cliché.

These are images of all they’ve got; concrete floors, small recreation boxes, steel bars, plastic mattresses and chrome furniture … all the while lit brightly by fluorescent bulbs and slat windows. These aren’t images taken for art-careerism, journalism or state identification. These are documents of a rarefied moment when, for a while – in the lives of these girls – procedures of the County and State took back seat.

When a member from within a community represents the community, the representation is above certain criteria of criticism. A prison pinhole photography workshop has very different intentions than any media outlet. Cliche is not a problem here; it is a catalyst.

The simulation and reclamation of visual cliche (in this case the obfuscated hunched detainee) is doubly interesting. Why the frequent use of the foetal position? Why did the girls choose this vulnerable pose to represent themselves? Was it on advice? Was it mimicry? Was it part of a role they view for themselves? Why don’t they stand? Emotionally, what do they own?

As in evidence in some images, one hopes that some of these girls are friends. This selection of shots share a single predominant common denominator; the psychological brutality of cinder block spaces of confinement. Companionship seems like a small mercy in those types of space.

These photographs should knock you off your chair. I am in doleful astonishment. In the absence of faces, how powerful and essential are hands?

For now, consider how visual and institutional regimes square up.

Since the original publication of these images, they have been viewed tens of thousands of times. More than any other photographer – famous or not – these images by anonymous teenage girls have been by far the most popular ever featured on Prison Photography. That appetite shows that when prisons and struggle and creativity are presented in a meaningful way, images can be used as a segue into wider discussion of the underlying issues.

The Remann Hall project was done as a part of the education department program at the Museum of Glass in partnership with Pierce County Juvenile Court. This comment sums up the importance but also the fiscal fragility of these arts based initiatives:

“The Remann Hall project was an incredible project, which culminated in an outdoor installation at the museum and many of the participants coming to volunteer and participate in education programs at the museum after they were released. It was one of the many incredible programs I was lucky enough to be part of there. A book of poetry, artwork (and I think some of the photos in that link) was produced as well. The whole program was a great model for how arts organizations can do meaningful outreach in their communities. Unfortunately, the program was cut one year before the planned completion, due to budget concerns.”

[My bolding]

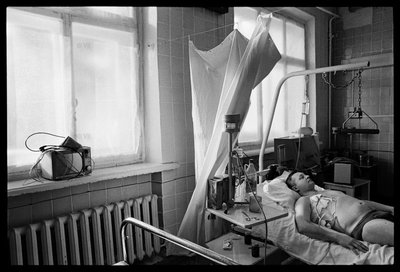

A TB patient at Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #3. Photograph and caption © James Nachtwey/VII.

“Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty and stress“.

Merrill Goozner, The Center for Science in the Public Interest.

“Sixty percent of all new cases of tuberculosis have resulted from the rapid growth of the post-Communist prison archipelago”.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Aug. 26th, 2008

Tuberculosis (TB) was under relative control in the former USSR. Soviets had lifestyles, nourishment and conditions of living that kept disease at bay. When communism fell, so did a civil order in many areas. The phalanx of activity that filled the vacuum involved new systems, new relationships, new businesses and new criminal opportunities.

The prisons filled in a society that needed to organize itself before it could organize it’s transgressors. The prison population swelled to 1.1 million (it is now down to little over 700,000). Post-communist prisons held malnourished, crowded populations with weak immune systems; they have been described as ‘Tuberculosis incubators‘.

Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. TB patient/prisoner gets a chest x-ray. Treatment is supervised by Partners in Health in partnership with the government TB program. James Nachtwey/VII

TB is best treated with various labour intensive methods known under the umbrella-term Directly Observed Therapys (DOTs). Due to TB’s many different strains – each with different drug resistancies – case by case treatments differ according to patient reactions to drugs. At the least, a patient must be observed and his/her drug regime modified over a 6 month period. For Multi-Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) the treatment can take as long as two years. And, MDR-TB & XDR-TB are increasingly common among prison and civilian populations of Tomsk and other Siberian urban centers. Unfortunately, closely monitored drug regimes are improbable in over-stretched and poorly funded state systems.

It wasn’t always so dire. The former Soviet provided a regular supply of drugs to abate disease amongst its prison population, but those supplies were interrupted in the fall of Communism – sporadic and incomplete treatments gave rise to multiple resistant strains of tuberculosis. To compound this the side effects of drugs were enough to discourage patients, and rarely, if ever, did courses of treatment go with a prisoner into his community following release.

TB patients smoke cigarettes in the smoking room of Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #1. James Nachtwey/VII

James Nachtwey‘s mega-promoted TED prize crusade addresses the spread of Extremely Drug Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB), its mutant forms and human tolls. This excellent Guardian article notes Nachtwey has photographed the epidemic worldwide, from Siberian prisons to Cambodian clinics.

A prisoner who was convicted of murder was moved from prison to the TB ward of Battambang Provincial Hospital, Battambang, Cambodia when he was diagnosed with TB. He is coinfected with AIDS. James Nachtwey

Nachtwey stands with Sebastião Salgado in the “super-photographer” stakes. They both make the ugly beautiful.

Both Nachtwey and Salgado have inspired others to action and both believe firmly in the power of photography to change existences … even in a time when such sentiment is derided as old-fashioned, false idealism.

But, despite the odds, Nachtwey has succeeded in forcing his work into the conscience of millions. For some his work is an inspiration for social justice; but for others his work is a sub-conscious default to guilt, despondency and powerlessness to help others less fortunate.

James Nachtwey puts human faces to global suffering. And we are outraged. Or we feel we should be outraged.

I think Nachtwey wants us to believe in ourselves as agents of change. Nachtwey deliberately chose Tuberculosis – because while the situation is critical, it is not terminal and TB is theoretically entirely curable. Beating TB on a global scale is dependent on the behaviours of individuals and their communities.

Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. A prisoner proves to a nurse that he has swallowed his daily oral TB medication. The prisoners receive treatment through metal bars in order to give security to the nurses. Treatment is supervised by Partners in Health in partnership with the government TB program. © James Nachtwey/VII.

Nachtwey’s work extended beyond the prison walls in Tomsk and went into the public clinics (some images included here show those facilities); TB is no respecter of human walls or demarcations. Regional, economic poverty will spike rates of TB.

A TB patient has excess fluid drained from his chest a Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #1. James Nachtwey/VII

The worst thing we could do here would be to think that TB is a disease of other nations and other peoples. In Pathologies of Power (2004), Paul Farmer wrote about the New York prison system’s huge Tuberculosis epidemic of the mid-nineties, “By some estimate, it cost $1 billion to bring under control”. The strains that arose in the NYDoC have been directly related to the resistant strains of the former Soviet Union. Tuberculosis is latent within one third of the world’s population. Tuberculosis needs only the conditions for its growth.

Paul Farmer, of Mountains Beyond Mountains fame has taken the lead on combating TB, as well as other infectious diseases, amongst the world’s poorest populations. He worked with Partners in Health partly funded by a Soros Grant to “develop demonstration tuberculosis control projects which could become a model for replication throughout Russia.”

A nurse prepares a daily injection for TB patients at Tomsk Regional Clinical Tuberculosis Hospital, Building #3. James Nachtwey/VII

Prison Photography blog has focused twice previously on photographers’ responses to the USSR and its aftermath – the Gulag and the new prisons that arose. While Anna Shteynshleyger and Yana Payusova are working with very different issues, regions and populations they – along with Nachtwey’s work – remind us of the severe problems facing parts of modern Russian society. Unfortunately, and certainly in the case of Tuberculosis, these problems exist in other nations also. Nachtwey focused on TB because it was not – despite being a global problem – on the radar of most people. That sounds like something I’d say about prisons and prisoners’ rights.

Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. A patient/prisoner receives a daily medical injection. The prisoners receive treatment through metal bars in order to give security to the nurses. Treatment is supervised by Partners in Health in partnership with the government TB program. James Nachtwey/VII

For more information on XDR-TB read the Action – Advocacy to Stop TB Internationally website, and the Center for Disease Control & Prevention website. For the most accessible and recent article, read Merrill Goozner’s 2008 Scientific American article about Russian Tuberculosis strains which also includes a audio segment with a clear explanation of the situation.

A TB patient/prisoner receives his daily oral medication at Correctional Treatment Unit #1, a TB prison colony in Tomsk, Siberia. © James Nachtwey/VII.

James Nachtwey built his reputation as a combat photographer.

He was always reluctant to be the focus of media attention but after 5 Capa Gold Medals for War Photography he couldn’t escape the curiosity of Christian Frei who made the extraordinary film War Photographer. Nachtwey comes across as an articulate, self-isolated journalist-force devoted to his craft and courteously distant to others; here is a clip.

Nachtwey has done interviews here, here and here. Read an interview about his 9/11 pictures, and associated videos on Digital Journalist. The images were published in TIME.

He worked in Rwanda for his book Inferno.

View his TED Prize acceptance speech and the consequent October 2008 launch of his XDR-TB project and Flickr pool.

Today, March 11th 2009, marks the twentieth anniversary of the first COPS episode. Producer, John Langley, and his cohorts celebrated the when the first show of the twentieth season aired at the back end of last year. Allow me to reflect also.

At overcrowded jails, like this one in Marion County, IN, inmates must sleep in portable containers. Credit: Inside American Jail

This is not really a day of celebration. Personally, I loathe the show. It is lazy, cheap and exploitative. In that regard, it paved the way for all the reality TV on the box today. Off my soap box.

It is worth noting that the 1988 television writers strike gave rise to COPS airing on screens. A desperate Fox Channel signed up after Langley had tried and failed pedaling the format for over six years. Lucky for him. But he was no slouch and worked the opportunity when it arose. Langley struggled early in his career. My guess is his PhD in Aesthetics took his thinking outside of the rote and predictable circles of Hollywoodthink. But TVland came round eventually and Langley has since distinguished himself as a true pioneer of America’s most-loved lowbrow art form.

Inmates in this Utah jail aren't digging an escape tunnel. They're learning to garden. Credit: Inside American Jail

Three years ago, Langley Productions introduced a spin off show that went off the streets and into the jails. Inside American Jail has ventured into sites of incarceration across the nation including the circus-like Maricopa County Tent City. The show won high ratings when the Las Vegas County Sheriff detained O.J.Simpson.

A sign at a Maricopa County jail reads "Vacancy." The rates are good but the atmosphere is lacking. Credit: Inside American Jail

In many cases the TV cameras show the true harsh realities of institution after institution with stretched resources warehousing troubled folk with few opportunities for rehabilitation. This doesn’t stop them from hamming up the quirks of jail time as evidenced by the promotional images and campy captions (shown within this article) drawn from the show’s website.

Mmm-mmm-good. An Iowa State Penitentiary inmate shows us what lunch in jail looks like. Credit: Inside American Jail

With most debates, nothing is cut and dried and an insightful article in the New York Times shows a vaguely compassionate point of view from Langley – who, let’s be honest has made his fortune of the back of America’s criminal justice exploits.

Having seen America’s prison population soar to more than 2.2 million, and with widespread prison overcrowding in California, Mr. Langley says he now believes the nation should be reconsidering which crimes should be punishable by imprisonment. “A lot of our attention is dedicated to arresting people who have drug problems,” he said, “when the real solution may be to rehabilitate them.”

And for your viewing pleasure here’s the ridiculous promo for Inside American Jail

This interview allows Langley to describe where Inside American Jail fits into the larger television ecosystem.

Morgan Spurlock is a decent guy. I’d like to have a beer with him. He lays it out straight. Prisons & jails are boring and hopeless. He knows this because he spent 30 days in a county jail just outside of Richmond, Virginia.

Spurlock nails it. “One of the most surprising things about prison is that you are pretty much left on your own. all you can do is kinda suck it up and fall into a pattern. I’m gonna get up, gonna eat, gonna play cards, gonna watch TV, gonna do some push ups, do some sits ups, write a letter, read a book….”

He continues, “People will be in their rooms or down here – just hanging out, you know, on the phones. The punishment is the monotony. This is it. You don’t have to think. You’re in jail. There is no thinking involved. And you’re feeding the machine. And you feel like that … you don’t feel like a person in a lot of ways.”

Spurlock elaborates “I haven’t seen a tree in over two week;, I haven’t seen one blade of grass; I haven’t breathed fresh air. It gets to you being in here … it really does. I see people like George and Randy who keep making the same mistakes over and over and over again. What is the system doing for these guys? They’re stuck! I see this cycle that were putting people in and punishing people for problems we could be helping them with. And the prisons and jails are just becoming a dumping ground. It really is a place that feels hopeless.”

Spurlock even challenged his sanity by agreeing to a 72 hours stretch in solitary confinement. Spurlock couldn’t comprehend how Randy (mentioned earlier) spent a year in solitary.

Great series. Great episode. Sobering reality. Spend 45 minutes of your life and witness the monotonous and expensive warehousing of society’s misfits.