You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison Theatre’ tag.

Earlier today, I posted House of the Dead (or How We See and Expect Tropes in Photographs of Russian Prisons) with images of blighted prisoners from art history. Regimented and downtrodden, the subjects of these historical works seem to me like precursors for the B&W grey photographs of Russian prisons, even today.

It was a set-up of sorts.

I used a selection of Sebastian Lister‘s photographs to illustrate my point, but I didn’t show you the majority of Lister’s portfolio, nor did I tell you why he had visited Prison Colony 29, Perm in Russia. (Sebastian, I hope you don’t mind my chicanery!)

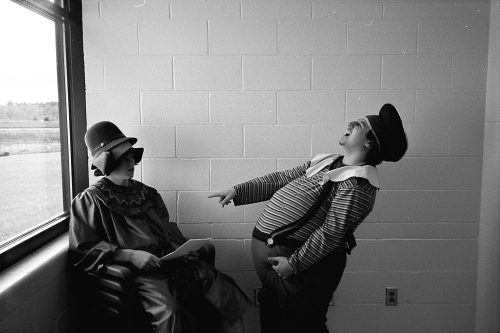

Elsewhere in Sebastian’s portfolio are unexpected images of costume, make-up, curtain calls, cross-dressing, pressured script-reading, nervous rehearsals and opening night applause.

Sebastian joined Alex Dower, director, actor, musician and artistic director of Creating Freedom, an international production company working in prisons. For more information, click here and then on the ‘prisons’ tab. Russia Today produced a wonderful half-hour documentary about Dower’s project.

Prison theatre is a common mode of arts rehabilitation in Russia, and Sebastian Lister’s documentary photographs are valuable insight into the “movement”. Perm Colony’s players are diligent creatives and their activities allow for more positive representations of prisoners in the Great Bear nation.

If you’d like to see more, Sebastian has posted more images on his Facebook page.

Scroll down to read my Q&A with Sebastian.

How did you get involved?

I became involved with Theatre in Prison: Territory Festival 2009 having studied acting & directing with Alex Dower. We were trained in the science of acting by the Russian Sam Kogan in London. It seemed fitting to be taking Kogan’s system ‘back home’. It is a rigorous, research based approach which appeals to those with a strong work ethic. For the most part the prisoners relished the opportunity and thrived under Dower’s leadership.

Tell us about Alex Dower’s work in Russian prison theatre.

Dower is a pioneer in that his project was the first high-profile prison theatre project in Russia. It caught the eye of the authorities, some of whom now regard theatre (and perhaps the arts in general) as having a role in rehabilitation. The media interest was aided by the fact that Alex and I are British. Arrangements were complex – we didn’t have the go-ahead until a month or so before. The show was beamed onto a big screen in Perm during the Territory Festival 2009. Crucially, I would say Dower nurtures the prisoners as artists in their own right without any hint of condescension.

How seriously did they take the acting?

As a group the prisoners set about their job with a high degree of diligence. There were some stand-out levels of commitment. In fact, Igor, one of the cast of Chekhov’s “The Burbot” has been offered a job in the professional theatre. And ironically a former neo-nazi murderer played the Jewish lead in “My First Goose” by Babel, a story for which the main theme are fear and courage.

Why does prison theatre prosper? What is the psychology behind it?

I think prison theatre prospers because it is an opportunity for inmates to learn from the characters they play, to exercise their imaginations and to acquire a sense of freedom on stage, thus escaping from the confines and drudgery of their daily lives. There is also the thrill of an audience – including inmates and parents – witnessing this transformation. It is an occasion for them.

One negative aspect of the experience was the come-down the prisoners felt after the show. Future projects should take this into account.

How many of the prisoners would have attended theatres before imprisonment?

I don’t know the exact figures but I would say that barely any of the prisoners had been to the theatre before imprisonment. Most prisons (I’m not sure about the high security ones) have a theatre of some kind.

What are the motivations for the actors?

The motivations for the actors come from the challenges of the characters in the stories – Chekhov’s “The Burbot”, Babel’s “My First Goose” and “Butterfly” written by Albertik Sadrutdinov, one of the prisoners. Characters were discussed and interpreted in the first week of rehearsal. Tanja Arno, an actress from Moscow was the only member of the cast not from the prison.

What other activities are available to them at Colony 29, Perm?

Albertik Sadrutdinov (now free) gained a qualification in building fireplaces whilst in the colony. He also spent time running, meditating, working out in the gym, reading, and playing in a band. On our first day, during quite a media scramble, I saw prisoners in class learning geometry. There is also a “working zone” with a timber yard and metal working shop.

Do either you or Dower plan more prison theatre coverage?

Dower plans to direct in a prison in Kazan, Russia in November 2011, and in Columbia in February 2012. Whether I accompany him or not depends on the funding available.

It sounds asinine to describe a prison as beautiful. Perhaps, the warm tones of the theatre-house in Kharkiv’s penal colony are a lure. But, I don’t want to budge on this; Maslov’s images are sumptuous.

Let us not forget though, the photographic series, however beautiful, is the product of specific circumstances. The more we know about these circumstances the better equipped we are to understand them and their content. Last week, Sasha and I talked over Skype about the details of the project.

How did you arrive upon the subject?

I had a couple of friends who had been running a theatre class in a prison in Kharkiv, Ukraine. I thought it was a great subject so I went along. Theatre performers aren’t what you expect to see in a prison. Being an actor is a ridiculous notion for criminals; you’re basically putting yourself in the position of the fool. The prison was maximum security so they were in there for serious crimes. At the beginning it was … kind of creepy, but then I got used to it.

I wanted to shoot with film. Initially, the warden said I’d have to use digital equipment, but I explained it was essential I used film and showed him some of my images. In the end, he permitted it.

It looks like you were you there for the final performances. How long had they been rehearsing and how many times did you visit?

They’d been working on the play for 9 months. I went in three times, but most of the shots from the project were taken on the day of the main performance.

What message did you hope to communicate with the project?

I go into all projects very open, without really knowing what it’s going to be like and if I will actually have anything at all in the end; what can I see? What can I tell? I think this is best.

Some of your subjects seem uncomfortable with the camera?

Yes. It is understandable as cameras aren’t something they are used to. Some don’t want to be seen for obvious reasons. Those acting in the troupe were more open to being photographed. I felt like during the new experience for them with this theatre they opened new horizons, but generally in prison the feeling is that the camera is not your friend.

I actually tried to shoot in two prisons, they other being a women’s prison but nothing came out of that project. The women acted very differently around the camera. Every time they saw the camera they’d change something. They’d usually smile. They would present themselves for the camera. The women always smiled. Once, I caught a glance of a female prisoners glaring at a male guard. It was a real wolf glare. I lifted the camera, but instantly she saw me and changed her look. Her eyes became those of kittens.

Perhaps this desire to perform or adapt for the camera by female prisoners is something you could work with in the future? Deborah Luster worked with the females in the Louisiana prison system making portraits of them in full theatrical costumes.

Yes, it would be interesting to shoot there again. But also, people aren’t totally truthful. They can’t talk about things that are difficult. I wasn’t allowed in their cells. The experience changed me. Not massively, but it did make me look at things a little differently.

In Ukraine can one assume certain things about the prison population? I ask this because in America’s medium security prisons where men can be serving long to life sentences, some may not be there because they are violent offenders. It is the non-violent men who are warehoused who seem to lose most through harsh sentencing. Does this mix of offender-types occur in Ukraine?

I cannot say. Of course, I never asked. One inmate did say to me, “You don’t have to pretend to respect me. You know I am in here because of something terrible I did.” But, I wasn’t pretending to respect anyone. These people were new for me, if you don’t consider the place where the [project] took place you are not able to form any prejudice.

Do you know what percentage of the men would eventually be released?

No, but I know some were due to be released very soon. One actor was due to be released one day before of the performance, but he preferred to stay for another week so that he could perform the show.

Right before show began I took a shot of a woman in the audience. I will never forget this moment. Later I found out she was a mother of one of the inmates in the troupe. She had come to tell him that his brother had died on the outside. She waited until after he’d finished the show because she didn’t want to ruin his performance. It was only afterward when I found this out I understood why she did not smile during the show.

And how was the show?

The dramatics were amazing to see. Many of the men struggled over and above their usual habits to get the lines out. The play was The House that Swift Built, which is a fiction about a house full of ridiculous items and fantastic people. Jonathan Swift tells unbelievable stories and plays practical jokes, the nature of existence in and outside the house is questioned. The players have the potential to transform their lives. Of course it was interesting to see this done by prisoners.

Still, many of the lines were delivered with arrogance. Even in soft conversation, the actors came across as brash. They are used to being in a defensive position so there was always a strange arrogance … or little aggression.

Did the inmates see your prints?

Yes, I sent prints to the prison. If there was a shot with two prisoners in it, I’d send two copies. I don’t know how they divided all the works among the guys but I know they got them.

Did you ever have to secure model release forms?

[Laughs] No. I only had to agree on the project with the warden. The fact my friends had been there a while also made my case easier. The warden was forward thinking by Ukrainian standards. He was interested in the publicity it would gain for his prison.

What are the general thoughts of prisons among the Ukrainian public?

That they are places you shouldn’t go. Prisons are tough everywhere. After you get out, you just have a new set of complexes.

How do former-prisoners fare in Ukraine? For example, ex-prisoners in the US have to petition to gain their right to vote back. How does it compare?

Ukrainian prisoners can vote in prison. But, more generally, prison is forever a stain on your character. Human rights violations occur in prisons all the time – stabbings, abuses of power by the guards. You hear about these things on the news. But these instances are just pieces of sand on the beach. It could be a much larger problem. Perhaps it is but we don’t hear about it.

Well, it is an amazing glimpse for us all to get at an arts program inside a Ukrainian prison. What equipment did you use?

I shot with a Kiev 6S, a 6×6 medium format camera. It is bulky and heavy. I really liked working with it but I was always very visible to the prisoners with this thing in my hands. And the sound that it makes is beyond any politeness.

What comes next?

I have two things on. I have just got back from Donbass, a region in Eastern Ukraine where I was doing a story on coal miners. It was an amazing experience, because for 20 years nothing has changed there except dramatic decline of population. There are small towns that lived off coal mines in Soviet period, but many mines were shut down or there are places where 5-6 thousands people worked and now there are 50-70 miners. It’s sad and fascinating area. The story will be out in a few weeks. I am also working on a show of photographic portraits for a gallery in Ukraine.

How do you pick your subjects?

I do what I think is important. I don’t plan too far ahead. I’ll be interested to see what happens in the near future with the industry.

You heard this month about Christopher Anderson saying, “The death of journalism is bad for society, but we’ll be better off with less photojournalism. I won’t miss the self-important, self-congratulatory, hypocritical part of photojournalism at all. The industry has been a fraud for some time.”

I didn’t but he could be right. There are trends in photography. When the trends change, there seems to be two types of response. The first is to chase and feed the trend. The second is – in the uncertainty – to stick to what is valuable to you, and that will usually be something you like. The best work will always come form that second approach. And as for the market; the market is like the ocean. It can change three or four times a day. There’s no use in trying to predict that.

True. Thanks Sasha

Thank You.

Sasha Maslov has shown this work before at Vewd and at his Lightstalkers profile.