You are currently browsing the monthly archive for March 2010.

The five boys who came to illustrate the class divide. Photograph: Jimmy Sime/Getty Images

Ian Jack wrote a glorious piece in today’s Guardian about Jimmy Sime‘s iconic image.

‘The photograph that defined the class divide’ describes 70 years of misreadings and its use as illustration for shallow assessments of Britain’s class disparities.

Jack is masterful in his analysis because he keeps it based in fact. The consequent lives of the five boys (which are not what you’d expect) are ultimately the critical blow to all the users and abusers of Sime’s image down the years.

“When a newspaper had asked the three men to get together to reconstruct the picture at Lord’s, one of them refused. I could see why: which of us would want to be remembered as a stereotype, especially in a class war where we’re given no choice of sides?”

Jack doesn’t dismiss the notion that Britain is still divided by class. To the contrary he says that Britain remains the European nation with the biggest gap between rich and poor. He (and I) can see that these arguments about UK inequality are better made with relevant illustration and not this nostalgic claptrap that does nothing to inform or elaborate.

” If a photographer wanted to re-create Sime’s picture, he might be faced with five boys dressed much the same, in jeans and brand names. Giving a superficial impression of equality, the picture would be even more of a lie than before.”

Just to prove the entrenched and idle use of Sime’s photo right up to present day, Jack finishes with this:

“What picture accompanied the Daily Telegraph’s report in January 2010? Sime’s, of course; the same as Picture Post had published in January 1941. There they were again: Wagner, Dyson, Salmon, Catlin and Young, doomed for ever to represent our continuing social tragedy.”

Brilliant stuff!

© Nico Bick

I just received an email from FOTODOK who present this month State of Prison, an exhibition with work of Nico Bick (The Netherlands), Carl de Keyzer (Belgium) and Mathieu Pernot (France). Also included – I am proud to say – are two photographers I’ve interviewed for Prison Photography – Stephen Tourlentes (United States) and Jürgen Chill (Germany).

© Jurgen Chill

FOTODOK statement:

“Photographing official institutions such as schools, government buildings, prisons and old people’s homes often goes hand-in-hand with limitations. PR and communication departments conscientiously guard their image and impose restrictions on photographers.”

“Even so, photographers still succeed in making individual and meaningful series in these places that go further than PR photos. From surreally painted Siberian prison camps to screaming family members outside the prison walls.”

© Mathieu Pernot

Federal Prison, Atwater, CA, 2007. © Stephen Tourlentes

The curator is photographer Raimond Wouda (The Netherlands) who himself has taken a look at the impression of institutional architecture upon its users, most notably the social spaces of Dutch high schools.

Throughout 2009, Raimond Wouda reported on his research on FOTODOK’s website. This process and all the findings of the past year have been compiled into a collection of words and images. The publication will be presented during the opening. I’d love to get my hands on that!

– – –

The exhibition runs from the 26th March to the 25th April 2010. An opening will held this week at 19.30pm on the 25th March at Van Asch van Wijckskade 28, Utrecht (map).

From the ZONA series. © Carl de Keyzer

Maurizio Anzeri

Asger Jorn

Ever since Maurizio Anzeri was roundly acknowledged as the star (here and here) of Paris Photo last November, his embroidered portraits have hung in a stasis awaiting the key association which my visual memory was willing upon them.

It only took six months, but the penny of association dropped: Asger Jorn‘s Defigurations (1962). Both artists appropriate existing images with humour, a touch of spite and avian motifs.

As Jorn used flea-market paintings and vintage subjects, so Anzeri picks up vernacular photographs and family portraits. Given their choice of materials you might think that they hold some reverence for the original object, and yet their surface interventions are violent, in most cases obliterating recognisable features.

Maurizio Anzeri

Asger Jorn

Maurizio Anzeri

Asger Jorn

JAIL GUITAR DOORS, headed by Billy Bragg, is a program that bring musicians and instruments to prisons in the UK. Thanks to a conversation between Bragg and the superintendent of Travis County Correctional Complex, JAIL GUITAR DOORS expanded its program into American jails.

Bragg and Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine among other musicians played live and collaborated with inmates at the Austin jail. The theory is one of music therapy. Bragg left six guitars inside the institution.

Bragg began JAIL GUITAR DOORS in 2007 naming the program after The Clash song of the same title. Since its inception, 32 prisons and more than 300 guitars have been part of the program.

Listen to the full story on NPR, visit the website for JAIL GUITAR DOORS, link up on the JGD’s Facebook page and a bit of local news here.

“No, it was not a random shooting. There was a group of three police officers. One officer took aim and shot Fabienne in the head.”

Fabienne’s father, Osama Cherisma, March 2010

Michael Winiarski and Paul Hansen recently returned to Port-au-Prince with the specific intention of following up on the fortunes of the Cherisma family.

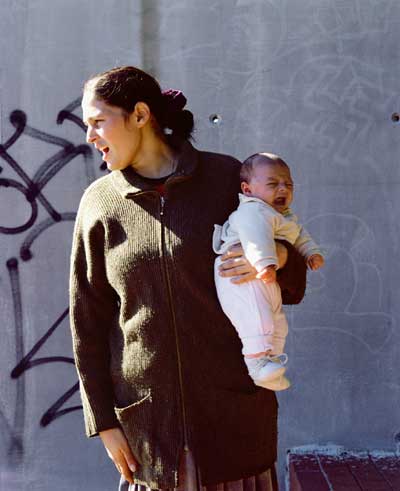

Fabienne's family (left to right): Father, Osama Cherisma, brother Jeff, 18 years, his sister Amanda, 13 years, and mother Amante Kelcy. Photo: Paul Hansen

Following my interview with Winiarski, I had asked rhetorically what the Cherismas may feel about the international coverage of their daughter’s death. I was raising the issue of media and journalists’ responsibilities toward the subjects of their stories, and more specifically I was wondering if the Cherismas would ever be interviewed at length to elaborate on their experiences since that terrible day.

Well, a part answer can be provided in the actions and article of Winiarski and Hansen who published this story on the 13th March. (Swedish original / English translation):

– Osama says he knows the identity of the killer – a high ranking police officer from their own neighbourhood.

– The family have not filed a police report because they are too scared. They say the police are watching them daily.

– They have not talked to local media and only talk to Winiarski and Hansen of Dagens Nyheter because they are foreign journalists.

– Osama dealt with the body directly because he didn’t trust he’d see his daughter again if he handed her corpse over the police and authorities.

– Although their house still stands, it is so destabilised they live in a tent city.

– The schools of Jeff and Amanda, Fabienne’s brother and sister, were both destroyed during the earthquake.

– Jeff, Amanda and their mother Amante all – understandably – still feel extreme pain and emotion. Osama cannot sleep.

– Fabienne is buried in Zorange, north of Port-au-Prince. It is the village of Fabienne’s grandmother.

– – –

ALSO IN THE ‘PHOTOGRAPHING FABIENNE’ SERIES

Part One: Fabienne Cherisma (Initial inquiries, Jan Grarup, Olivier Laban Mattei)

Part Two: More on Fabienne Cherisma (Carlos Garcia Rawlins)

Part Three: Furthermore on Fabienne Cherisma (Michael Mullady)

Part Four: Yet more on Fabienne Cherisma (Linsmier, Nathan Weber)

Part Five: Interview with Edward Linsmier

Part Six: Interview with Jan Grarup

Part Seven: Interview with Paul Hansen

Part Eight: Interview with Michael Winiarski

Part Nine: Interview with Nathan Weber

Part Ten: Interview with James Oatway

Part Eleven: Interview with Nick Kozak

Reporter Rory Carroll Clarifies Some Details

Part Fourteen: Interview with Alon Skuy

Part Fifteen: Conclusions

PART ELEVEN IN A SERIES OF POSTS DISCUSSING PHOTOGRAPHERS’ ACTIONS AND RESPONSES TO THE KILLING OF FABIENNE CHERISMA IN PORT-AU-PRINCE, HAITI ON THE 19TH JANUARY 2010.

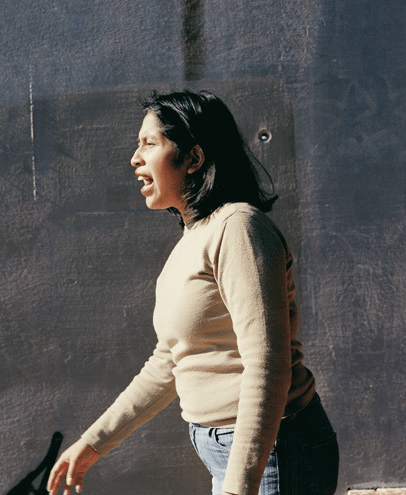

Photo: Nick Kozak

On 20th January, the day after Fabienne’s death, Nick Kozak was walking through an unfamiliar neighbourhood of Port-au-Prince. Kozak’s fixer had warned him that the area might be unsafe. Then a man and two youths approached him.

The exchange was brief. Kozak took two photographs of the three. At the time Kozak did not know the details of Fabienne’s killing.

Photo: Nick Kozak

The man was Osama Cherisma, his daughter, Amanda and son, Jeff.

Describe the interaction.

I was approached by them. I photographed them because they asked me to help.

I was with a guy who was helping me with translating and our exchange was very quick. I was a bit nervous about my surroundings as I believe we were close to Cite Soleil.

I did not know that his daughter was shot by police. From what I had understood in our short time together was that there had been some sort of gang related shootings and that she was an innocent bystander.

How long was the exchange?

Very short, about 4-5 mins.

When you say they were looking for help, what sort of help?

They were looking for help in the sense of being heard I think. They were distraught, of course, and wanted to be heard. I guess they just wanted to talk to someone who might be able to tell the ‘world’ about their tragedy. Sadly, I did not even learn much about Fabienne Cherisma at the time, interestingly, we are putting the pieces together now.

Do you think it was because you had a camera in hand that they thought you could help?

Yes, I think that because I was a foreigner with a camera they thought that I could ‘help’, but I won’t theorize much as our encounter was indeed very short.

Do you expect that this family has any chance of achieving justice (however that is defined) or is Haiti too unstable to deal with the death of this single girl?

I can’t imagine that this family will achieve justice in Haiti for this death but mind you I only spent five days there and my knowledge of the country’s situation is limited. I do believe that the country is too unstable and has too many ongoing problems that have been so severely augmented by the earthquake for this family to be properly attended to.

Who was talking to your translator? The father?

Mainly the father, Osama was talking, yes. I was writing down a bit of information about him and his family on a scrap piece of paper which I think I can still find at home.

What impression was left as you parted? Did the family seem as if they had a purpose to pursue?

I was a bit confused and unsure of what had exactly transpired. It left me sad but we had a destination and felt unsafe (because of what the guys I was with had told me) in the area that we met them in.

I’m not sure how to answer the second part of the question. By that time, I was already skeptical or soured by the whole place in that I felt that their fight for whatever they were pursuing was sort of futile. I thought that the girl had been shot by a stray bullet from the guns of thugs and that justice would be close to impossible to get. Hope that makes sense.

Nick’s assessment makes sense, but the entire situation does not.

How do we reconcile the world’s media focused on a family and their dead daughter one day and then their total abandonment the next? I am not saying the media, individual journalists or anyone is responsible for the welfare of the Cherismas, I am pointing out that often images are just props for disaster consumption and virtually no-one gives these people a second thought.

At the beginning of my first ever post on Fabienne Cherisma I quoted Guardian journalist Rory Carroll:

“The question is not whether Fabienne will be remembered as a victim of the earthquake but whether, outside her family, she will be remembered at all.”

Similarly, will Fabienne’s family be remembered?

– – –

ALSO IN THE ‘PHOTOGRAPHING FABIENNE’ SERIES

Part One: Fabienne Cherisma (Initial inquiries, Jan Grarup, Olivier Laban Mattei)

Part Two: More on Fabienne Cherisma (Carlos Garcia Rawlins)

Part Three: Furthermore on Fabienne Cherisma (Michael Mullady)

Part Four: Yet more on Fabienne Cherisma (Linsmier, Nathan Weber)

Part Five: Interview with Edward Linsmier

Part Six: Interview with Jan Grarup

Part Seven: Interview with Paul Hansen

Part Eight: Interview with Michael Winiarski

Part Nine: Interview with Nathan Weber

Part Ten: Interview with James Oatway

Part Twelve: Two Months On (Winiarski/Hansen)

Reporter Rory Carroll Clarifies Some Details

Part Fourteen: Interview with Alon Skuy

Part Fifteen: Conclusions

PART TEN IN A SERIES OF POSTS DISCUSSING PHOTOGRAPHERS’ ACTIONS AND RESPONSES TO THE KILLING OF FABIENNE CHERISMA IN PORT-AU-PRINCE, HAITI ON THE 19TH JANUARY 2010.

James Oatway is a Johannesburg based photojournalist employed at the South African Sunday Times. James was in Haiti from January 17th until January 28th. On the morning of the 20th – the day after the shooting James’ diary dispatch for the SA Sunday Times was published.

Fabienne was shot at approximately 4pm. What had you photographed earlier that day?

Earlier that day, not far from where [Fabienne was shot] I had seen a young man taking his last breaths. He had been stabbed in the neck and chest by fellow looters in a fight over a box of toothbrushes. People were stepping over the dying man. Then about five minutes later some men stopped and put his body onto a motorbike and took him away.

Did you see Fabienne get shot?

I was about two meters away from the policeman when he fired the fatal shots. He was behind me and fired two quick shots. Not knowing that anyone had been struck I spun around and photographed him gun in hand. Police were arresting a man on the street corner. I photographed that for about thirty seconds and then someone shouted that someone had been shot. I ran to where she lay on top of those frames. She didn’t have plastic chairs with her as some reports claimed.

How many other photographers/reporters did you see at the scene?

There were initially about five or six photographers there. While we were shooting a man came and took money out of her hand. I shot for about fifteen minutes. Word must have got out about the shooting because more and more photographers arrived.

Do you know the photographers’ names?

I only knew two other photographers names… Jan Dago and Jan Grarup. Both Danish.

How long was it until her family and father arrived to carry away Fabienne’s corpse?

Then about twenty minutes later the father and brother arrived. The father was already hysterical. I followed him onto the roof. He lifted her head up and then realized that it was his daughter and dropped her again. Then he and his son began carrying her away. It was at least three kilometers and there were many stops. Her sister and other family members joined the procession. There was a lot of screaming and wailing.

I withdrew at this point. There were too many photographers … and I became emotional. I had also stood on a nail which had gone deep into my foot. There must have been about fifteen photographers.

How did others behave?

There was a bit of jostling but nothing too bad or disrespectful.

How was the atmosphere?

The atmosphere was surreal.

Anything else?

I have her surname as “Geismar”. I have no reason to doubt my fixer who I saw write it down in his notebook. I will stick to Geismar as being her correct surname.

Prison Photography has consistently used Cherisma, the spelling used by The Guardian on its first dispatch following her death.

Elsewhere, I have seen the spellings ‘Geismar’ and ‘Geichmar’. Likewise, Fabienne’s father is referred to as both Osam and Osama, and sometimes both in the same publication. Fabienne’s mother has been named Armante, Armand and Amand Clecy in the reporting of different media.

– – –

ALSO IN THE ‘PHOTOGRAPHING FABIENNE’ SERIES

Part One: Fabienne Cherisma (Initial inquiries, Jan Grarup, Olivier Laban Mattei)

Part Two: More on Fabienne Cherisma (Carlos Garcia Rawlins)

Part Three: Furthermore on Fabienne Cherisma (Michael Mullady)

Part Four: Yet more on Fabienne Cherisma (Linsmier, Nathan Weber)

Part Five: Interview with Edward Linsmier

Part Six: Interview with Jan Grarup

Part Seven: Interview with Paul Hansen

Part Eight: Interview with Michael Winiarski

Part Nine: Interview with Nathan Weber

Part Eleven: Interview with Nick Kozak

Part Twelve: Two Months On (Winiarski/Hansen)

Reporter Rory Carroll Clarifies Some Details

Part Fourteen: Interview with Alon Skuy

Part Fifteen: Conclusions