You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Commercial’ category.

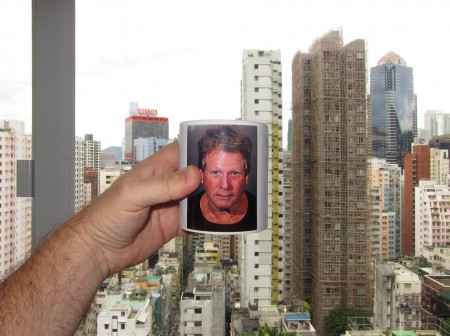

Michael Wolf’s mug. Photo by Michael Wolf for Hermann Zschiegner’s Mugshot Mugs project.

Hermann Zschiegner‘s cheeky Mugshot Mugs had me smiling. He wanted to make a comment on privacy and create and excuse to make contact with his heroes.

Zschiegner Googled and downloaded images of celebrities’ booking photos, printed them on mugs at Walmart and sent the mugs out to, as he puts it, “twenty people that have been of great influence to me in one way or another or whose work I have admired over the years. Some of the people who received a mug are friends, but most don’t know me very well – or at all. […] All I asked from the participants was to place the mug anywhere in their home and take a picture of it. The way the mug was framed in the picture dictates just how much privacy they were willing to give up.”

Zschiegner’s comparison of mugshots with paparazzi and within a framework of privacy-rights is thought-provoking:

“Federal booking photographs are automatically entered into the public domain in the United States, and can be obtained by anyone through the Freedom of Information Act. While designed as a tool to index and collect the images of potential criminals in a database, the publication and distribution of these pictures is an astonishing act of invasion of privacy. Institutionalized, but in effect not much different of paparazzi pictures shot from afar.”

Zschiegner is an active member of the Artists’ Books Cooperative (ABC) an international network created by and for artists who make print-on-demand books. Many of the recent book-projects within ABC have made overt use of public, internet and appropriated digital imagery. In a recent email, Zschiegner described ABC as “slow and spontaneous, small and excessive, serious and funny.” Okay, I’m amused so I’ll let you have it both ways.

Correctional Services of Canada trainee in training to become a prison guard, Kingston, Ontario. © Jeremy Kohm

When Jeremy Kohm sent through this portrait, I saw the boots and the overalls and presumed it was a photo story on fishermen or lumberjacks. Wrong. A trainee prison guard.

I asked a few questions.

Tell us about the training facility and the town it’s located in.

Kingston, with a population of approximately 120,000, is located on the main highway roughly at the midpoint between Toronto and Montreal. Kingston is a town comprised of university students (18,000 who attend Queen’s University est. 1841), military personnel (as there is a large Canada Forces Base in the vicinity) and the Kingston Penitentiary (which houses some of Canada’s most notorious criminals).

The training facilities are a stones throw to Kingston Penitentiary which, having opened in 1835, is the country’s oldest prison. The penitentiary is considered maximum security and houses some 400 inmates – of which 40% have received a life sentence.

Do all trainees do range shooting?

When talking to the trainees what struck me the most was the brief nature of the job training program. It consists of four phases; 4-8 weeks of online training, 2-4 weeks of workbook assignments, 8 weeks of practical training and then 2 weeks of on-site training.

Most of the facilities were relatively pedestrian from a visual perspective – so I decided to photograph some of the trainees at the range once they had finished their target practice. This portion of the training was a mandatory element in their job preparation.

Who are the trainees? Where did they come from?

Some were just looking for a job whereas a few others were a little more idealistic and cited the reason as “wanting to make a difference.” The backgrounds were equally varied, some had a military background whereas others had no experience and decided this career was purely an alternative to becoming a police officer. It really was quite varied.

Most of the trainees were in uniform, however, this one subject for some reason was able to wear clothing of his choice. In all honesty I’m not too sure why or if he was exempt. He allowed me to take the photograph as long as his identity remained hidden.

Anything else?

I do vaguely remember that punishment was given out in the form of push-ups. Punishable offences were essentially exactly what you imagine, things like tardiness and negligent safety behaviour.

While the trainees were waiting for my assistant and I to rig up the lights they were scouring the shooting range for unfired bullets. Apparently, they could redeem the bullets as a means of reducing the number of pushups required. Their eyes were constantly scanning as they paced in attempts to discover this odd form of currency.

Huh, weird.

Scar © Sye Williams

Sye Wiliams photographed in Valley State Prison for Women, Chowchilla, California. His portfolio was included in the June 2002 COLORS Magazine.

Williams’ entire Women’s Prison portfolio can be seen on his website.

It is a bit of a time machine without a specific destination. The images are prior to 2002, we know that much. But it is anyone’s guess which particular year. (I have asked Sye and will update with the answer.)

Williams’ choice of film-stock, the era-less prison issue coats and baseball t-shirts, all amount to a almost “date-less” space and time. Even the hairstyles span any number of decades. Yet, this is what prison is for many inmates; prison is a time of stasis, if not reversal. When time is not your own, how should it matter? And when one’s time is detached (in an experiential way) from that of dominant society, then it stands to reason that very different rules of judging the days, measuring value, gauging worth, choosing behaviour, and – dare I say it – opting for styles, would shift significantly.

Officer © Sye Williams

It is not often prison photographers take portraits of correctional officers (mostly down to legal reasons).

Williams’ Officer (above) is a slippery image. The officer maintains the same steeled look as some of the inmates. The fact that she wears a helmet with visor, and that this particular portrait exists within a portfolio of weapon-still-lifes and an photograph depicting model-hairdresser-heads all unnerves me a little.

It is not that women’s prisons are uncontrollably violent. To the contrary, they’re more likely sites of boredom. However, as a viewer to Williams’ work, I find myself adopting the same caution as the staff and administration. Prisons are places where daily activities are shaped by the need to always prepare for the worst case scenario.

Williams manages to subtly suggest the latent violence of prison, and given recent reports (California Women Prisons: Inmates Face Sexual Abuse, Lack Of Medical Care And Unsanitary Conditions) he is probably close to the truth. Apparently, Valley State Prison for Women in Chowchilla is less dangerous than it once was, but it remains a notorious prison for women.

In the deviant milieu of prison, even when time ceases to exist, vigilance necessarily remains a constant.

View Sye Williams’ entire Women’s Prison portfolio.

Beauty School © Sye Williams

Front cover

COLORS magazine first fell onto my radar last year when reviewing Broomberg & Chanarin’s work. It cropped up again in March when I delved into Stefan Ruiz’s early career. All three were creative directors in COLORS continually rotating roster of aesthetic leadership.

Based in the north Italian town of Treviso, COLORS is part of the publishing activity of Fabrica, Benetton’s communication research centre. Benetton’s searing brand-making hit my young retinas with its controversial United Colours of Benetton (billboard) ad campaign of the early nineties.

Besides Saatchi and Saatchi, Benetton was the only time in my childhood I was aware of the names behind billboard products. That is an assumed level of cultural penetration, but I’m working from precious memory too much to determine its significance.

[As an aside, Enrico Bossan Head of Photography at Fabrica and Director of COLORS Magazine was co-curator for the 2011 New York Photo Festival. He also founded e-photoreview.com in 2010, which delivers without no-nonsense video interviews with photographers.]

The 50th edition of COLORS (June 2002) focused specifically on prisons. From the introduction:

With over eight million people held in penal institutions the prison population is one of the fastest growing communities in the world. In the United States, a country which holds 25% of the world’s prison population but only 5% of the world population, prisons are now the fastest growing category of housing in the country.

For COLORS 50 we have visited 14 prisons in 14 countries and asked a difficult question: Is it possible to rehabilitate a person back into society by excluding them from it? We spoke to murders, rapists, pedophiles, armed robbers, thieves, frauds, drug dealers, pick pockets, high-jackers and prison wardens. In most cases the stories we heard confirm one thing. That prison does not work. In COLORS 50 we ask the inmates themselves to suggest alternatives.

The magazine is 90 pages of portraits and interior landscapes. I came to this collection of work late (in my research here at Prison Photography) and in many ways it challenges many of my former presumptions. This edition is a precursor to the “VICE-aesthetic” celebrating the battered and broken, and I’d be happy to dismiss it if it weren’t for the long-form statements made by the prisoners, which are printed with care and without censorship.

The issue includes bodies of work by photographers I was previously unaware of including Juliana Stein, Vesselina Nikolaeva, James Mollison, Charlotte Oestervang, Suhaib Salem, Federica Palmarin, Mattia Zoppellaro, Ingvar Kenne, Kat Palasi, Dave Southwood, Gunnar Knechtel, Pieter van der Howen and Sye Williams. I will be featuring selections of these photographers over the next few weeks.

I bought the paper edition, but you don’t have to as the entire Prison/Prigione Issue 50 can be viewed online.

Above all, while browsing the images and stories of the magazine, I am really pressed into thinking about the ease with which a commentator can politicise and argue against the prison system in America, but be flummoxed when asked to appreciate prison systems elsewhere. Benetton uses the common theme of incarceration to raise questions, but I am at a loss to think of common answers to tackle the pain, blood and damage done to individuals in their lives before, during and after imprisonment.

At a surface level this is car-crash photography; a look inside worlds we’ll never know, but at its heart it is a call to think about the nature of humanity and to think about the capacity for humans to kill, to survive, to get addicted and to repair and to forgive.

Back cover

I was interested to discover that photographs of San Quentin inmates played a formative role in Stefan Ruiz‘s career. At 4:45mins, Ruiz talks about his position as an art teacher at San Quentin and his compulsion to make portraits.

From a battered Fujifilm box held together with gaffer tape, Ruiz pulls out a wire bound album of prison portraits:

“I really wanted to take pictures of them so I started taking all these photos. I put this whole little notebook together … and I would carry this box [everywhere]. This was before laptops. I used to bring this to Europe all the time and I’d show this. This was what got me jobs.“

Ruiz goes on to explain that he was employed by Caterpillar to imitate the look of those San Quentin portraits. Ruiz’s contact at Caterpillar then moved to Camper and the relationship continued. After Camper Ruiz went to COLORS Magazine as Creative Director (Issues 55 – 60, April 2003 – April 2004). All the while, Ruiz was perfecting his “well-lit” and “polished” style.

Some observers are turned off by the fusion of art/documentary/fashion employed by Ruiz. Common criticism of this multi-genre work is that it can depict poverty as glamorous, violence as eye-candy, and people as consumable props in a visual world obsessed with surface.

The flaw to these dismissive crits is that cinema has been forging this type of imagery for decades; yet, we expect slick augmented reality in the moving image. Ruiz’s use of lights instead of B&W film and the blur of a Leica is hardly an attack on documentary and certainly not on realism (since when has photography ever plausibly claimed a monopoly on realism, anyway?).

Ruiz’s portraits have a solid footing in reality; they are devoid of photojournalist cliche and require participation from the subject. And as far as commercialism is concerned – at least in the case of COLORS – the relationship of money to Ruiz’s aesthetic experiments is acknowledged.

Ruiz likes to “work with the person.” From telenovela actors to hospital patients and clinicians and from rodeo queens to refugees, Ruiz has connected with his subjects through a transparent discussion about what they can achieve together with a device that records and stores their likeness.

The VBS profile of Stefan Ruiz* is a great introduction to his past, present and future trajectory. Highly recommended.

* I apologise for the crude use of screengrabs in this post.

Ex-warden Rick Lamonda at the site of America’s deadliest prison riot causing reform in 1980. Aqua Fria, NM. 2009

Photographer, Jesse Rieser was inside New Mexico’s decommissioned Federal Prison. From the four images on his site, I can’t work out whats going on. Possibly outtakes from a fashion shoot (see photo Elizabeth) although the picture above looks like it should belong to a confessions “human- interest” story … y’know the type … the sort of tale that only comes out when almost everyone involved is almost dead.

This laconic portrait reflects what I picture Sheriff Ed Tom Bell to look like. Bell is the protagonist and part narrator character in Cormac McCarthey’s No Country For Old Men.

“It was surprising for Norfolk to discover that the infrastructure of the internet age is as imposing, ugly and ‘real’ as the cotton mills, mines and factories of Victorian Manchester. Like pulling back the the curtain to find that the Wizard of Oz is actually a little old man, the cloud is no more than giant buildings full of computers, air conditioning units and diesel back up generators; there’s nothing fluffy or vaporous about it.” (Here)