You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

I wrote a piece about Chris Nunn‘s photographs in Ukraine, for Vantage.

Read Accidentally Photographing War In Ukraine.

Nunn, an Englishman, has been hopping flights to Ukraine since 2006 — first with a Ukrainian a girl he dated at uni, and later to trace his roots.

In early 2013 and without a jot of the language he went in search of a connection to the country and its people.

To quote me:

“He had no idea that he was about to be wrapped up in a regional conflict that would draw the world’s attention. His photography became less a personal journey and more an accidental documentary of a nation in steady decline toward war.”

Nunn even ended up in camp with Ukrainian Army conscripts. His mix of portraits and environmental shots is quite poignant. I received an email from Nunn this morning:

“Donetsk. I had no idea at the time that I’d probably never be able to return there, as a normal civilian, [when I made the photos]. Maybe, now, only possibly with special press permission? It’s a mix of good and bad memories … which is true for Ukraine, in general, I think.”

Who knows what to think? With ceasefires crumbling, who knows what comes next?

MEETING THE PRISONER CLASS IN POLAND

One might argue that, in the world, there are as many reasons for making an image as there are images. Polish photographer Kamil Śleszyński was curious about how prisoners thought about freedom and “why many prisoners couldn’t live outside [of prison] and would come back again.”

Carrying a camera along with you in these inquiries may or may not help you find answers, but in any case you’ve some images to reflect upon, to lean on, and to mold toward some sort of conclusion.

Śleszyński reached out to me and shared his project Input/Output, which consists of photographs made within a prison and in a re-entry centre that supports ex-prisoners. Both facilities are in the city of Bialystok. The images were made between September 2014 and February 2015.

Using a limited number of sheets of 4×5 film forced Śleszyński to be selective with his exposures. The majority are posed portraits. I wanted to find out what he discovered during the project.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Click any image to see it larger.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): In the intro text to Input/Output you suggest that prisoners are institutionalized and are bound by what they learn in prison. Can you explain this more?

Kamil Śleszyński (KS): The man who goes to prison needs to adjust to the rules prevailing there. On the one hand, the rules are created by the Polish prison system, on the other hand by the prisoners themselves.

For example, Grypsera is a prison subculture. Those prisoners who adhere it rules are known as Grypsera too. They have own language which is based on polish language. Grypsera was created in the past century and determined the tough rules, hierarchy and standards. Today, these rules have loosened somewhat but many of them are still alive.

The prison environment is permanently stigmatising. This is perfectly illustrated by words from the book “The Walls of Hebron” written by Andrzej Stasiuk: “To the prison you go only one time. This first. After that, there is no prison. There is no freedom too. All things are the same.”

Polish prisoners are not taught independence because it is not technically possible within their reality. Resocialization is a key issue, but most progams toward it are not enough. Therefore, freed prisoners cannot deal with freedom itself. It is easier to get back behind bars where everything is either black or white.

PP: Many of your subjects have tattoos. Are tattoos important in Polish prisons?

KS: Tattoos were an important element of prison subculture. Tattoos on their faces and hands allowed quickly define the criminal profession. Military ranks tattooed on their arms, define the length of the sentence. There were a lot of different types of tattoos. Only deserving criminals could have it.

Today, these rules are loosened. Tattoos do not always have the prison symbolism, sometimes are associated with religion.

PP: You shot in a prison in Bialystok. What is its reputation?

KS: The closed wards were the worst, because prisoners are spending 23 hours a day in a cell. Prisoners can be a little crazy as a result.

PP: Why did you want to photograph inside?

KS: I grew up in the neighborhood of the prison. Often I was walking near by the prison walls and watching prisoners. They were standing in the windows bathing in the sun. I was wondering why they were behind the walls. This curiosity stayed with me.

PP: How did you get access?

KS: The year ago I met director and journalist Dariusz Szada-Borzyszkowski. He was working with a prisoners. He cast them in performances. He put me in touch with the right people and gave valuable hints. His help greatly accelerated my work.

PP: What were the reactions of the staff?

KS: Prisoner chiefs had a positive attitude to the project. In one of the prison facilities I had a lot of creative freedom.

PP: What were the reactions of the prisoners?

KS: Gaining the confidence of prisoners takes a long time, and this was a key issue for the project. Prisoners are understandably distrustful — they’re afraid that someone from the outside can deceive or ridicule them.

One of the prisoners told me that he don’t want to work with me because prisoners are not monkeys in a cage. I spent a lot of time to convince him that I wouldn’t misrepresent him. In the end, he was involved in the project so much that he convinced other prisoners to cooperation with me.

I was shooting with an old camera 4×5. Many of prisoners were interested in my shooting technique because they had never seen such equipment. It was a new experience for them.

PP: Did the prisoners have an opportunity to have their photograph taken at other times?

KS: Prisoners are photographed by the staff upon entry into the prison and at the time of their departure. During imprisonment is not possible to be photographed … unless they are involved in a project like mine.

PP: Did prisoners have photographs in their cells?

KS: Sometimes prisoners have photos of their loved ones in their cells. This helps to survive in isolation.

PP: Did you give prisoners copies of your images?

KS: Prisoners are collaborating when it is profitable. The photos were a reward for participating in the project. Many of them sent photos to their loved ones.

PP: What do people in Poland think about the prison system? And of think prisoners?

KS: People don’t know much about prisons and prisoners, and guided by stereotypes. They want to know how it is inside, but do not want to have anything to do with the prisoners. They are afraid of them.

I hope that such projects like mine, will help to change those points of view. I got scholarship from the Marshal of Podlaskie region for the preparation of a draft photo book about the prisoners. It wasn’t easy, but the scholarship suggests to me that views are slowly changing.

PP: Overall, is the Polish prison system working or not? Does it keep people safe, or rehabilitate, for example?

KS: The polish prison system puts too little emphasis on resocialization.

PP: Thanks, Kamil.

KS: Thank you, Pete.

© Richard Ross

I never thought I’d see a trans prison guard. I didn’t think transgender persons worked in the corrections industry and — given the culture of prisons — I did not expect that a trans person would ever want to.

However, she exists and her name is Mandi Camille Hauwert.

The Marshall Project continues to uncover surprising and new angles on this nation’s prisons. Their profile of Hauwert Call Me Mandi: The Life of a Transgender Corrections Officer is no exception. It is a story with which Richard Ross, a well-traveled photographer of prisons, approached them. Alongside the photographs are Ross’ own words.

Hauwert began work at San Quentin as a male, but transitioned in the job and has been taking hormones for 3 years. She faces hostility from fellow staff.

It’s worth noting how dangerous prison systems are to transgender folk. A few weeks back, I attended Bringing To Light a conference in San Francisco, at which I learnt the routine brutalisation of LGBQIT persons at the hands of the prison system — threats of rape, the use of solitary “for protection” and all its associated deprivations, the denial of prescribed hormones, and many other daily humiliations.

Janetta Johnson spoke about surviving a 3-year federal sentence in a men’s prison. She and her colleagues at the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project (TGIJP) now help trans folk deal with trauma and reentry following release.

Unwittingly and without buy-in, transgender prisoners swiftly expose the oppressive logic and total inflexibility of the prison industrial complex. Follow TGIJP‘s work and that of the other organisations that presented at Bringing To Light. Their work often goes unrecognised in the larger fight for reforms and abolition, but it precisely the prisons’ adherence to patriarchy and outdated constructs of gender that establishes the tension and abuses.

Ross’ Call Me Mandi: The Life of a Transgender Corrections Officer is a brief but illuminating feature. Read it.

Tracey: “I lost my family. I lost my job and I lost my home. I spent 14-and-a-half years in the Department of Corrections.”

PUSHED TO THE MARGINS

What do you do when you law prohibits you from living within a reasonable distance of any of society’s communal spaces and social services? That’s the question thousands of sex offenders find themselves with, and the perpetually-liminal existence they inhabit.

ABSENT DEBATE

I’ve not written about sex offenders — imprisoned or otherwise — very much on this blog. This is due in most part because I’ve not a wealth of knowledge. But it is also because it is an easy population to ignore. This is my failing. Sex offenders are a group that receive little-to-no sympathy or understanding. And, this, despite their crimes being massively different from one another and their pathologies and psychological profiles dictating their offence but not, by any means, their potential improvement and contributions into the future. Prison Photography has lazily sidelined the issue as to maintain a safe distance from one of society’s trickiest topics within criminal justice.

Sofia Valiente‘s photographs of ‘Miracle Village’ a community of registered sex offenders in Florida give me the opportunity to tackle this. Valiente has just released a book of the project with FABRICA and the work was featured on The Marshall Project this week.

Miracle village was founded in 2009 by Pastor Dick Witherow, whose ministry helps sex offenders reintegrate into society by providing them with onsite housing, employment, and counseling.

Valiente’s book contains writings by 12 sex offenders who live in the isolated community in West Palm Beach County, Florida.

A (VIRTUALLY) IGNORED ISSUE

Firstly, I should say that this is not the only work of this type. Danish photographer Steven Achiam made images of sex offenders in a trailer park, also in Florida. I’ve known this work for years but, again, never quite dared to bring it up.

Secondly, I will say that the laws against sex offenders living in proximity to children differ state-to-state, are almost arbitrary, mostly unenforceable and rarely consider whether the crime was against a child in the original case.

Furthermore, exclusionary zones put off-limits ludicrous amounts of roads and public thoroughfares. For example in Revere, Massachusetts, the Prison Policy Initiative mapped out what proposed laws would look like and found that 99% of the city would be off-limits.

Finally, I take my information from those I trust most. Laurie Jo Reynolds — an incredibly effective campaigner, serial grant winner, darling of the anti-prison movement, and hero of mine — has long argued against sex offender registries which put individuals on the list as risk and do not improve public safety. Reynolds also says that registries do not prevent crime only pile expensive punishment, admin and enforcement on top of a severely misunderstood problem.

All that said, we need to approach the issue of sex crimes with less fear and judgement and realise we have not yet found the most sensible, safe, restorative, economical or humane ways to deal with this tough, tough issue. Maybe Sofia Valiente’s images are an invitation to do so?

Richard: “Up until the age of 18, I had a terrible stutter. I hated talking. I was always a good student and often knew the answers to the questions asked in class. However, I never raised my hand because I dreaded being called on. My stutter was bad, and when I was talking to a girl it was even worse. When I discovered Internet Chatt in 1988, and I could communicate without having to talk, it was the greatest thing ever.”

“Living in Miracle Village is quiet, peaceful, yet isolated. When people call me about jobs, they never know where Pahokee is.”

Paul on his porch. “I don’t know when I started making bad choices.”

Gene in his El Camino.

Matt exercising in the back shed in the village with David and Lee. “Growing up with my mom was enough, I’m ready to move on. All I did was go to school and take care of the house. It was like living in boot camp. She was the one that called the cops on me in order to protect her job or so she said.”

Ben taking a walk around the sugarcane fields that surround the complex.

Objects on Rose’s refrigerator include a photograph of her children (their eyes were obscured by the photographer to protect their identities).

Lee laying down inside his room. Lee went to prison when he was 18 and served 12 and a half years of his 15 year sentence. He is serving the other 2 and a half years on conditional release. His restrictions include a 7pm curfew, no driving other than for employment purposes- not alone, no internet, monthly urinalysis, no contact with minors even family members, GPS monitoring and paying the cost of his supervision. He must register as a sex offender for the remainder of his life. “You can clean me up, put me in the ‘right’ clothes and give me an honorary membership, but I will still be that outsider and that is that.”

Gene laying down with his dog Killer for a nap. “As a sex offender I can not trust anyone…. All they have to do is call 911 and say that a sex offender has bothered them and Bang! I am in jail. No questions asked.”

Doug after a day of working outside. He helps out in the community by doing occasional lawn work and other maintenance jobs. Doug lived in a tent in the woods prior to coming to the village. Because of distance restrictions he was unable to go home after serving his time and had difficulty finding a place to live. “After I got into trouble I became homeless and couldn’t get a job so I lived 2,500 feet into the woods.”

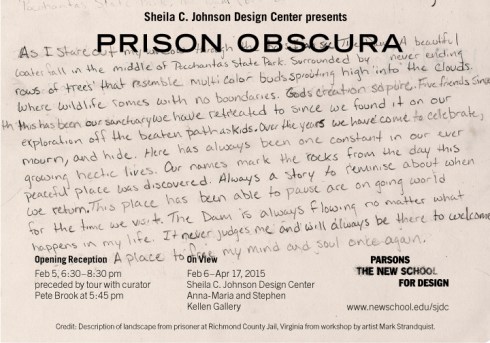

After stints at Haverford College, PA; Scripps, CA; and Rutgers, NJ, my first solo-curated effort Prison Obscura is all grown up and headed to New York.

It’ll be showing at Parsons The New School of Design February 5th – April 17th:

Specifically, it’s at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, located at 2 West 13th Street, New York, NY 10011.

On Thursday, February 5th at 5:45 p.m, I’ll be doing a curator’s talk. The opening reception follows 6:30–8:30 p.m. It’d be great to see you there.

Here’s the Parsons blurb:

The works in Prison Obscura vary from aerial views of prison complexes to intimate portraits of incarcerated individuals. Artist Josh Begley and musician Paul Rucker use imaging technology to depict the sheer size of the prison industrial complex, which houses 2.3 million Americans in more than 6000 prisons, jails and detention facilities at a cost of $70 billion per year; Steve Davis led workshops for incarcerated juvenile in Washington State to reveal their daily lives; Kristen S. Wilkins collaborates with female prisoners on portraits with the aim to compete against the mugshots used for both news and entertainment in mainstream media; Robert Gumpert presents a nine-year project pairing portraits and audio recordings of prisoners from San Francisco jails; Mark Strandquist uses imagery to provide a window into the histories, realities and desires of some incarcerated Americans; and Alyse Emdur illuminates moments of self-representations with collected portraits of prisoners and their families taken in prison visiting rooms as well as her own photographs of murals in situ on visiting room walls, and a mural by members of the Restorative Justice and Mural Arts Programs at the State Correctional Institution in Graterford, PA. Also, included are images presented as evidence during the landmark Brown v. Plata case, a class action lawsuit that which went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States, where it was ruled that every prisoner in the California State prison system was suffering cruel and unusual punishment due to overcrowded facilities and the failure by the state to provide adequate physical and mental healthcare.

Parsons has scheduled a grip of programming while the show is on the walls:

Mid-day discussion with curator Pete Brook and Tim Raphael, Director, The Center for Migration and the Global City, Rutgers University-Newark.

Wednesday, February 4, 12:00–1:30 p.m.

Co-hosted with the Humanities Action Lab.

These Images Won’t Tell You What You Want: Collaborative Photography and Social Justice.

Friday, February 27, 6:00 p.m.

A talk by Mark Strandquist.

Windows from Prison

Saturday, February 28

A workshop led by Mark Strandquist. More information about participation will be available on the website.

Visualizing Carceral Space

Thursday, March 12, 6:00 p.m.

A talk by Josh Begley.

Please spread the word. Here’s a bunch of images for your use.

PARTNERS

At The New School, Prison Obscura connects to Humanities Action Lab (HAL) Global Dialogues on Incarceration, an interdisciplinary hub that brings together a range of university-wide, national, and global partnerships to foster public engagement on America’s prison system.

Prison Obscura is a traveling exhibition made possible with the support of the John B. Hurford ‘60 Center for the Arts and Humanities and Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

Sébastien van Malleghem has been awarded the 2015 Lucas Dolega Award for Prisons his four years (2011-2014) of reportage from within the Belgian prison system.

I’m a big fan of the work having previously interviewed Sébastien while the work was ongoing and applauded the time he spent three-days locked up in Belgium’s newest most high tech prison. That experience helped van Malleghem understand that there are some very thin but very significant thread that connect the cameras and lenses of security, with the cameras and lenses of photographers and journalists, with the cameras of news and entertainment.

In his formal statement to the Lucas Dolega Award, van Malleghem says:

These images reveal the toll taken by a societal model [the prison] which brings out tension and aggressiveness, and amplifies failure, excess and insanity, faith and passion, poverty.

These images expose how difficult it is to handle that which steps out of line. This, in a time when that line is more and more defined by the touched-up colors of standardization, of the web and of reality TV.

Always further from life, from our life, [prisoners] locked up in the idyllic, yet confined, space of our TV and computer screens.

In an interview with Molly Benn, Sébastien (mashed through Google translate) says a couple of valid things. They answer key questions young photographers have, firstly about access, and secondly about behaviour in the prison.

No one will tell you up front “You should contact so-and-so.” I went to see the mayor of Nivelles. I forwarded to the director of the prison in Nivelles, who referred me to a government worker. Those exchanges took 8-months. Every time I was asked to re-explain my project. Eventually, I received written permission by email but, still, each warden could still refuse me if he wished.

and

In prison, everything is constantly monitored. My first challenge was to get out from under the constant control. Upon entry into prison, you are immediately assigned an agent, supposedly for your safety but mostly to monitor what you’re doing.

But the prison officer ranks are often understaffed. I quickly noticed that they preferred to work their usual job than be my baby-sitter. So. I asked questions, showed interest in their profession, and I gained their confidence. After this, they let me work quite freely.

Basically, photographing in prison is a precarious exercise. I recall the words of one photographer who reflected on this best when he told me he never presumed he’d be let back in the next day or next week. He made images as if that day in the prison was his last.

Van Malleghem’s prison work follows on from years documenting Belgian police.

LUCAS DOLEGA AWARD

Lucas von Zabiensky Mebrouk Dolega grew up between Germany – his mother’s homeland, Morocco – his father’s – and France. Never one to respect authority for authority’s sake, he needled the inconcstencies and the inbetween spaces of persons’ experience and identity. On January 17th 2011, in Tunis, Lucas died on the streets amid a riot. He was covering the “Jasmin Revolution” in Tunisia.

The Lucas Dolega Award honours Dolega’s spirit and contribution. The award recognises freelance photographers who take risks in the pursuit of infomration and informing the world. Previous recipients are Emilio Morenatti (2012), Alessio Romenzi (2013) and Majid Saeedi (2014).

TWEETBOXES

Mom Were OK, Mississippi Gulf Coast, Mid September, 2005 © Copyright of Zoe Strauss

STRAUSS AT HAVERFORD

If you’re in the Philly area and you’ve got any sense, you’ll be making your way to Haverford College tomorrow for the opening of Sea Change, by Zoe Strauss.

Strauss will be there too. Talking and everything.

Friday, January 23rd.

Do it.

Drying Money, Mississippi Gulf Coast, Mid September, 2005 © Copyright of Zoe Strauss

TV on Second Floor, Mississippi Gulf Coast, Mid September, 2005 © Copyright of Zoe Strauss

This is my hometown, Toms River, NJ, 2012. © Zoe Strauss.

PRESS BLURB

In Sea Change, Strauss traces the landscape of post-climate change America. In photographs, vinyl prints, and projected images, Strauss treads the extended aftermath of three ecological disasters: Hurricane Katrina in the Mississippi Gulf Coast (2005); the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in Southern Louisiana (2010); and Hurricane Sandy in Toms River, NJ, and Staten Island, NY (2012). Lush and leveled landscapes; graffiti pleas and words of encouragement—Strauss’s camera captures lives decimated and dusting off: the fast and slow tragedies of global warming, the damage we can repair, and the damage we can’t.

THOUGHTS

I had no idea Strauss was working on a survey of disasterscapes in America. Following her 10 years of photographing in Philadelphia and celebrating the colours and characters of her beloved home city — and then presenting her photographs annually beneath Interstate 95 — it makes sense that Strauss would gravitate to the realest of struggles for real people at a time when real (climate) change is unleashing real events.

Sandy, Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon catastrophes left millions of Americans floundering, thousands dead, communities torn from the ground. In the immediate aftermath of such events, attention focuses on the official and governmental responses, but Strauss is more interested in the long tail of disasters and of informal vernacular responses. Strauss seems hell-bent on reminding us that after the camera crews leave, there’s still generations of rebuilding to be done (especially ecologically).

In Sea Change we see Strauss’ usual dark humor and restless documentation of the frayed edges of our nation. She’s holding up a mirror to the inconvenient messiness that we like to think we can deal with quickly and efficiently, but Strauss’ world is in a state of constant entropy, and it’s the invisible, the workers, the poor, the animal kingdom and the dissenters that lose out most when the shit hits the fan.

We all know that we’ve permanently altered our planet’s climate systems; we all know we’re on the hook. But we also know we can look anywhere-else, any time we want. And we know we don’t have to live on the Gulf Coast, or in the path of hurricanes. And we know that when things go south, we can turn our heads to the news and make a distant appraisal about whether the clean-up is happening quick enough or not, or watch some talking heads, or wag our finger at some government official.

Strauss’ victory in all her work — and particularly in Sea Change — is that she marries the visuals in her inquiries and her work so that they sync with her experience of the world. She is keeping herself honest through her photography. Perhaps Strauss can keep us honest too?

Foundational to Strauss’ work too is a deep respect. Zoe is irreverent, for sure, but she is also respectful of people. Entropy is going to happen; change is constant. People are going to win and people are going to lose, amidst change. That’s life. The degree to which people’s fortunes differ … and the degree to which people win and lose … and the degrees to which those statuses are kept permanent, that’s not just “life” though. It’s for us to decide how disaster will effect our collective in the long term. It’s for us to decide on the most equitable distribution of resources when many have literally been swept away.

When people fall down, we help them up. Rebuilding is everyone’s business. In Strauss’ world, love is the response to entropy and its disruptions.

NUMBERS

Running: January 23–March 6, 2015

Reception and opening talk with the artist: Friday, January 23, 4:30–7:30pm

PAPER

The exhibition is accompanied by a publication designed by Random Embassy, Philadelphia, featuring essays by artist Zoe Strauss; The New Yorker contributing writer Mattathias Schwartz; Helen K. White, PhD, Assistant Professor of Chemistry at Haverford College; and a poem by Thomas Devaney, MFA, PEW Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of Poetry, Haverford College.

Oiled Water Coming Inland, Waveland, Mississippi, Early July, 2010 © Copyright of Zoe Strauss

Billboard, Mississippi Gulf Coast, Mid September, 2005 © Copyright of Zoe Strauss

We’ll Be Back, Mississippi Gulf Coast, Mid September, 2005 © Copyright of Zoe Strauss

ANY QUESTIONS?

Contact (my mate) Matthew Seamus Callinan, Associate Director, Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery and Campus Exhibitions

mcallina@haverford.edu

Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA 19041

Tel: 610 896 1287

Don’t Forget Us, Mississippi Gulf Coast, July 2010 © Copyright of Zoe Strauss

Photographer, friend and fellow San Franciscoer Robert Gumpert will be exhibiting at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, California from January 25th to March 15th.

On show will be photographs from two projects — Gumpert’s ongoing Take A Picture, Tell A Story, and images from “I Need Some Deodorant. My Skin Is Getting Restless” which were made between 1996 and 2002 at the Alameda County’s Psychiatric Emergency Services at John George, Oakland. In both bodies of work, Gumpert uses oral history (audio and text interviews) to add description, depth and context to the experiences of his subjects.

If you’re in the Bay Area, I strongly recommend a trip through the Caldecott Tunnel out to Moraga.I’ve long been an admirer of Gumpert’s work, specifically Take A Picture, Tell A Story which is part of my curated effort Prison Obscura.

Prior to the public reception on January 25th, will be an hour long panel discussion with Gumpert; architect/activist Raphael Sperry; and psychologist/authority on solitary confinement Terry Kupers.

Click on the flier below to see it larger and glean all the critical information.

Tameika Smith, San Francisco, CA. SF CJ2. 9 July 2012.

Deborah Lee Worledge, San Francisco, CA. CJ1 Men’s jail. 4 April 2008.