You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

FERGUSON, THE ZINE

David Butow is raising cash on Kickstarter to fund the printing of a zine of his images made in Ferguson over the past 3 months. The images have been made, the edit done and the sequencing finalised. I’ve seen a PDF of Ferguson and it is a zine that is taut and emotional. It is also quite different from other projects I’ve seen coming out of Ferguson. Many of the scenes framed by Butow have multiple vignettes playing out in them all at once. They’re considered and crafted images. It’s both a photographers’ photography project and a statement relevant to all. It works as art and as political marker. It is relevant to documentarians and also, I think, will stand up to the test of time. Butow travelled to Ferguson twice — once after Michael Brown’s death and once after the grand jury decision not to indict Darren Wilson. As well as 34 photographs, Ferguson also includes raw interview transcripts used in the grand jury deliberations. One offers a nuanced view of the neighborhood where the shooting took place and of Michael Brown himself. “The work goes beyond the violence to offer an intimate and emotional portrait of the community’s reaction – from conflict to prayer – and puts the meaning of what occurred in Ferguson in historical context,” says Butow.

——-

FUNDRAISING, KICKSTARTING

Please consider backing this timely, no-nonsense, self-starting publication. Printed in California, using recycled paper and inks. 64 pages, 34 original B&W photographs. 8.5″ x 11″

Jerome at 15. © Zora Murff

Hey y’all. You might have heard about the launch of The Marshall Project, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization covering America’s criminal justice system. You might also recall that I was excited by the launch.

Excited because I think we’ll all benefit from having focused, smart and quirky analysis of America’s carceral, criminal and correctional territories. But, excited also, because I’ll be contributing features of photographers’ work.

OPENING GAMBIT

My first piece about Zora Murff, Tracked: A Photographer Reveals What It’s Like To Be A Kid In The System was published this week.

Here’s an excerpt.

In addition to slinging his camera, Murff works as a “tracker” for a program that provides low-risk juveniles alternatives to incarceration. He coordinates transportation to therapy and counseling sessions, contacts schools to make sure that the juveniles are attending classes, collects urine samples for drug tests, and monitors the juveniles’ locations through data from their ankle bracelets.

“My job is to be a consequence, to insert myself into their lives while the adolescents themselves are struggling to exert control over their development,” says Murff who wanted to capture how juveniles in the system are supervised and monitored, and how the resulting lack of privacy can impact their development.

“Cameras are typically used by the state to surveil,” he says. “I too am recording, but my camera is there in a collaborative capacity. I feel that the people I’m photographing have taken back a level of control.”

Read and see more at The Marshall Project

If you want to learn more about Zora Murff’s work you might be interested in this long interview I did with Murff on Prison Photography in January, 2014.

OPENING STATEMENT

I really can’t recommend enough the daily newsletter of criminal justice news put together by The Marshall Project’s Andrew Cohen. It’s called Opening Statement and it brings together the best links and most pressing stories. Indispensable. Get it!

When I was growing up, the dad of some kids at my school worked at the local prison. I had no idea what his day-to-day responsibilities were. Still don’t. This despite the fact I’ve since worked with, been on holiday with, and spent many weekends with the brothers and sisters in the family.

I have no idea, if the dad was involved in some extra curricula or fraternal pursuits; I don’t know if he wanted to even hang out with his co-workers outside of the prison. His job was a fact, but an unexplored and little discussed fact in the parish.

I also had no idea that the England Prison Service Football Association (EPSFA) existed. Not until Positive Magazine featured Riccardo Raspa‘s photographs did I learn of this 40-year-old organisation.

These are the best footballers in the country who happen to work as full-time prison guards.

The EPSFA arranges games between it and RAF, Army, and university football teams and other. It is fed by four regional teams made of the prison guards with the silkiest skills. Raspa photographed a single game and also followed one prison officer inside to photograph him at work. As such the information sways between the recreational tone of sport and the more serious business of control and power behind the bars.

Positive Magazine quotes, Michael Hayde, the England Prison Service coach as saying, “If a prisoner finds out what you are involved in and to what level it does make a difference to how they react and treat you.” And I can believe it. Football, particularly in Britain, is the great equaliser. It’s as accessible as chat about the weather or what you had for your dinner last night.

I’m almost inexplicably drawn to this project. The pictures are quite ordinary but they’re shot with care and some respect.

My care is probably due to nostalgia for the smells and sounds of an evening football match in Blighty and the unexpectedness of this project. (This story would never emerge in America).

But also, the prison staff are humanised here. I’ve said many times before that prisons, especially in America, are toxic places and everyone suffers to some degree. Prison staff are derided as second rate cops or, worse still, glorified babysitters. It’s a tough job and the disproportionately high levels of relationship/marriage failure and drug & alcohol abuse among prison employees testifies to that. Yes, there are corrupt officials and yes, abusive state employees are less seen — and possibly even ignored — because of the feared population they work with. That said, we cannot decarcerate and we cannot radically scale back on prisons if we are not focused on alternatives to incarceration. Bile and hatred for a profession will get us nowhere; it will only distract our energies from finding solutions. And that’s coming from someone who is well aware of the messed-up-shit prison guards have done when no-one is watching.

It is precisely because Raspa’s photographs ask us to view prison officers as individuals that I wanted to include it on the blog. It’s a tough proposition in many ways.

Megan Slade, author of the Positive Magazine, article thinks the EPSFA has got short shrift in the media.

“Despite being a national football team,” writes Slade, “little or rather hardly any press has been covered of the EPSFA, whether due to the nature of the profession this team is part of, or perhaps mainstream football leagues overshadow lesser known associations, they seem to go unnoticed.”

This is not surprising. I guess the quality of football is only just a small step above sunday league stuff. The operations of an amateur football team rarely warrant media spotlight — it has to be an exceptional case.

The lack of coverage here is nothing to be surprised or appalled by. In fact, it is wholly consistent with the distribution of everyday prison stories — you know the ones not about escape, riots, celebrity inmates, serial killers or dog-training programs.

All images: Riccardo Raspa.

You can follow Riccardo Raspa through his website, on his Tumblr, and Twitter.

BEYOND PRISON PICTURES

Isadora Kosofsky insists her project Vinny and David is not centered in narratives of incarceration.

“It is,” she says, “about a family and the battle between love and loss.”

Given that approximately a quarter of the images in the series were shot inside a locked facility, that initially seems a strange claim. Furthermore, as I look through Vinny and David, it seems as if the only certainly in the lives of they and their family is uncertainty, specifically an uncertainty brought about by incarceration and its collateral effects.

However, this is where we need to feel as well as look. This is where we need to spend time with Kosofsky’s subjects. If we do, we realise the photographer’s insistence is spot on. She wants to portray the boys not as prisoners, but as young people who happen to have spent time in prison. The distinction is important; it’s the only way she thinks her audience can empathize and connect.

YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHER, YOUNG SUBJECTS

Kosofsky met the younger brother, Vinny, first. It was late on a Tuesday night in a New Mexico juvenile detention center. As he posed for his mug shot, Vinny turned to the police officer to check he was standing on the right spot. Kosofsky watched Vinny enter the D-unit and silently sit in front of the television. He picked an isolated chair.

“When I met Vinny, I was 18 years old,” says Kosofsky. “I had previously documented young males in three different juvenile detention centers and youth prisons. Photographing my subjects in a detention environment limited their identities for I could only show a fragment of their lives. Vinny stood out amongst many of the males I met. He was the youngest boy in his unit, just age 13, but full of wisdom and sensitivity.”

Vinny was detained because he stabbed the man who was assaulting his mother.

“When my mom was being beat up, I was so scared. I wanted to defend my mom,” Vinny told Kosofsky. “I’m tired of seeing my mom get hurt.”

While Vinny was in the juvenile detention center, his older brother David, then age 19, was released from a nearby adult facility. David had been in and out of juvenile and adult correctional systems. He had been introduced to drug dealing at age 10. After his father went to prison, David was placed in foster care. At 14, David’s mother, Eve, was given custody, and David joined Vinny and two younger siblings, Michael and Elycia.

“David and Vinny have experienced deep loss and betrayal but yearn for love and a restored family,” says Kosofsky. “In the midst of turmoil, Vinny and David try to assume the hopefulness of youth. Vinny describes David as a father figure, and David views Vinny as the only person who appreciates him.”

COVERAGE AND RESPONSE

The series Vinny and David has received recent coverage in TIME and Slate. And plaudits.

Soon after the TIME feature, I received an email from a previously incarcerated man who described himself as an artist-activist. His opinion would suggest that Kosofsky was successful in her efforts to build a connection between the brothers and her audience.

“Unlike much work out there, this project shows humanity,” emailed the former prisoner. “People who have not been incarcerated may not realize the impact of this project but it is revolutionary. I have looked through a lot of photography, art and writing about incarceration. Kosofsky shows incarcerated males in a sensitive light. The pictures are heartbreaking and necessary. For a young girl, only 18, to have the courage to do a project like this is mind blowing. It is a rebellion.”

Coming from somebody familiar with the system, such an endorsement is better than anything I could give.

In spite of widespread coverage of Vinny and David in mainstream media, she and I were determined to produce something here on the blog, so I pitched a few questions that try to needle the gaps in the previous pieces and to bring us up to date on how Vinny, David and the family are doing now.

Please scroll down for our Q&A.

You can click any image to see it larger.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): You’ve mentioned a particular an ineffable connection with Vinny. How did that create moments for you to make powerful photographs?

Isadora Kosofsky (IK): In a prison environment that often promotes restraint, Vinny immediately revealed vulnerability, and tears fell down his cheeks as he spoke to me.

PP: He was different.

IK: The more intimate I am with my subjects, the more affective the image. Individuals, especially young males who are typically guarded, show vulnerability in front of the camera when they sense commitment and earnestness. I must share in my subjects’ struggles over a sustained period of time in order to forge a bond. I knew it would be a lengthy process before I could photograph moments from David’s life when his “mask,” as he calls it, was off.

I can’t drop into someone’s life, take pictures and then leave with those memories. The relationships I form with the individuals I photograph are more important to me than the actual image making.

Since I have never been incarcerated, I initially couldn’t empathize with Vinny’s incarceration. No one can say they know what it felt like for Vinny, at age 13, to be taken from his mother, handcuffed in the back of a police car, brought to a unit of strangers and handed a pillow. Yet, partaking in his and David’s life over time allowed me to recognize shared characteristics and emotions that brought me even closer to them.

PP: Do you think the power of the work might also rest on the fact that Vinny (as well as David and the family) is representative of so many children effected negatively by criminal justice in America?

IK: I hope the impact of the work lies in my intent to document Vinny and David’s story as I would that of my own family. I didn’t choose to photograph them because I felt that their situation was emblematic of a larger social issue. I chose to photograph them because I have an affinity to the love between two brothers who happened to both experience incarceration. Above all, I wanted this project to command a humanistic standpoint. I feel that there is already so much work about the system itself. Shooting solely at the jail site made it difficult for me to create a documentation that the greater society could identify with. I wanted to photograph Vinny and David in a relatable manner so that those looking at the images might feel that they could be their friend, sibling or son.

PP: Why did you want to shoot in a prison? Frankly, it’s the last thing on the mind of most 18 year olds.

IK: Ever since I was 15, I wanted to photograph inside a detention center. Unfortunately, due to my status as a minor, the administrators of the domestic facilities to which I submitted proposals rejected me. However, when I turned 18 and resubmitted my applications to the same facilities, some responded favorably, and I was granted access. I draw inspiration for my projects from childhood and personal experience. I began photographing when I was about 14, focusing mainly on the lives of the elderly. Around this time, I had a group of friends for whom delinquency resulted in police intervention. Some of them had been in juvenile detention, while others were on probation or had just been released from boys’ disciplinary camp.

We would meet at a shopping mall, where many teenagers gathered every Friday night, and they would tell me about their experiences with the juvenile justice system. I became particularly close to one male, and we began to spend time together outside our social group. He was the emotionally present listener whom I deeply needed at that time in my life. Unfortunately, my friend was arrested, and I lost contact with him.

Almost a year later, as I was photographing elderly women in retirement homes, I began to envision new projects and started to write proposals to correctional facilities. Even though 18 is young, I never thought of my age as a deterrent. I consciously wanted to be a young person photographing other young people.

PP: How have your thoughts about the prison industrial complex changed over the course of the work?

IK: One aspect that has struck me profoundly is that when one member is incarcerated, the whole family is too. As a relative or friend, one is powerless to intervene, waiting hours for phone calls, weeks for visits and years for legal decisions and then release, sometimes with an unknown date.

Incarceration is, paradoxically, a solitary and collective experience. Detainment isn’t localized just to a facility, for it leaves profound psychological effects, as it did on Vinny and David’s development. When David was cycling in and out of jail, a looming fear of loss hovered over the entire family.

PP: What can photography do, if anything, in the face of mass incarceration?

IK: I don’t know what photography can do in the face of mass incarceration. Every documentary photographer wants his or her images to repair the world. Ever since I shot my first picture, I have been guilty of this idealism. I strongly feel that a form of change occurs every time a viewer internalizes poignant images. We need more humanistic photography of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated youth. They are often individuals who come from troubled homes, and when we reject them visually and orally, we participate in reenacting their trauma.

We need to stop making their stories that of “others” and make their lives part of ours. When people look at the photographs of Vinny and David, I can only hope they empathize. I would then feel I have accomplished what I told this family I would do.

PP: How is the family doing today?

IK: Vinny, who just turned 16, has moved in with David, who now has a job and lives in his own apartment. David is committed to his role as a father. Both brothers are trying to establish a peaceful life after a traumatic upbringing and are optimistic that they will succeed. Healing is a slow process.

PP: Thanks, Isadora.

IK: Thank you, Pete.

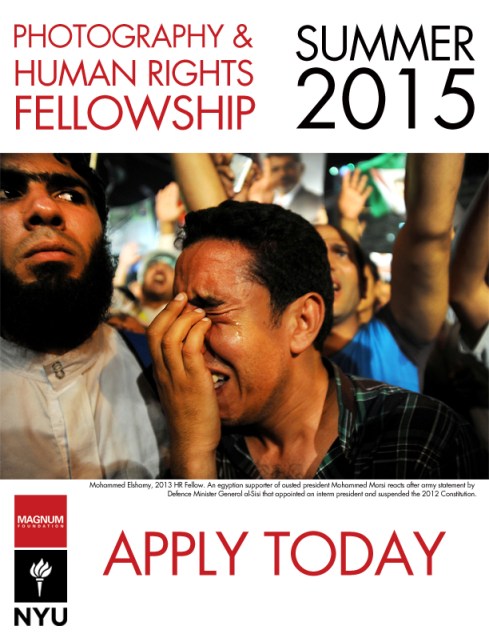

The Magnum Foundation Photography & Human Rights Fellowship is an all expenses-paid scholarship for non-western, regional photographers and activists to attend the Photography & Human Rights summer program at New York University.

Over the past 5 years, 21 fellows from 15 different countries have participated in the program.

Applicants must be:

– Emerging and professional students, photographers, activists, and journalists.

– Born and live outside of North America and Western Europe.

– Proficient in speaking, reading, and writing in English.

– Demonstrated a commitment to addressing/documenting human rights issues within their home country.

APPLY HERE

For more into contact Alexis Lambrou at alexis@magnumfoundation.org or 212-219-1248

Xavier Randolph dances with his father Frank Randolph during a Hope House summer camp program for youth with imprison fathers at the North Branch Correctional Institution in Cumberland, MD.

RAYMOND THOMPSON JR.

Raymond Thompson Jr. is a photographer, video journalist, educator and father.

In his Justice Undone Project, Thompson Jr. documents the leaching and negative effects of mass incarceration. He shows us how the poor are criminalised by society and kept down. He’s trying to get past stereotypes of Black America and does so by photographing the families and the communities outside of prison. So far, chapters of Justice Undone include A Dream Denied and The Browns.

Prisons touch nearly everyone in America’s poorest communities. One person’s imprisonment effects many others’ lives. The knock-on effects are profound. Locked up, exiled parents can mean extended family members are the primary care givers. Young children can lack a mother or a father or both for long periods. A child’s emotional and social development can be hampered and the incarceration of a parent vastly increases a child’s chances of being locked up later in life. The cycle continues.

In film, print and photography, America has a history of demonising young black men. In response, Thompson Jr. works to image all generations and races from America’s lower classes in an attempt to build empathy in his audience. So far, Thompson Jr.’s work has focused on African American communities but soon he is to venture into poor white communities in the Midwest, and to demonstrate that our broken criminal justice policies impact the poor. Prisons are a class issue just as much as they are a race issue.

The closer you look at the prison industrial complex, the better you understand society. Thompson Jr. is holding up a mirror in which we are all reflected. He was kind enough to answer a few questions I had about his photography.

[Click on any image to view it larger]

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): It seems your work on issues surrounding community, the war on drugs and incarceration is an ongoing endeavour. Is this the case? If so, tell us what you’re up to and what you’re working on now.

Raymond Thompson Jr. (RTJ): My project Justice Undone started as my master thesis while I was in graduate school in Austin, Texas. I originally intended only to do a story about the long term effects of incarceration on families and communities in East Austin, which is a predominantly African American and Latino part of the city. After I received a grant from the Alexia Foundation to continue the project, I expanded the project to Washington D.C and New Orleans.

In the 18 months since then, my wife and I had our first child and I took a job working as a video producer for West Virginia University. So, most of the last 18 months have been consumed with adjusting to life as a parent. The sleep deprived nights are decreasing. So, I’m slowly moving into the next stage of this project.

Even though I have never been incarcerated and my immediate family has not been directly affected by mass incarceration, I still feel a deep connection to the issue. I saw myself in the faces of the men, women and children navigating the prison system. Now with the birth of my son, I feel it is even more important.

There are several story angles in my project that still need covering. I’m currently in the process of researching and planning local Justice Undone stories for trip this fall and a trip to the midwest in the early spring. I’m currently based in West Virginia, which offers a chance to approach this work from beyond the lens of race and move it more towards class.

A boy stares though a window during a Friends and Family of Incarcerated People (FFOIP) car wash fundraiser in Southeast Washington, D.C. Friends and Family of Incarcerated People, a non-profit based in Washington D.C., offers a summer camp for children of incarcerated parents and other children whose parents are absent.

Members of ‘Mix Emotion’ go-go band pray before a performance at a community gardening event in the Lincoln Heights area of Northeast Washington D.C. Lincoln Heights is a crime plagued area and has a large number of low-income residents.

Several D.C. teenagers relax and socialize during the Friends and Families of Incarcerate People annual retreat in outside Charlottesville, VA. The goal of the retreat is to give youth a chance to experience life outside of their depressed D.C. neighborhoods.

A child looks at a car that had been broken into the night before a Friends and Family of Incarcerated People (FFOIP) summer camp in Southeast Washington, D.C.

PP: When and how did you move toward your current political conscience?

RTJ: In the 1990s, I was a teenager living in the suburbs of Virginia outside of Washington D.C. I watched the War on Drugs rage on my television screen. It was in these moments that I started to feel something was wrong. But I was not equipped with the knowledge or maturity to understand what I was seeing. On my television screen, I watched images of black men and boys dead or being led away in handcuffs. These visual images negatively affected how I felt about myself and other African Americans. Part of the reason for working on Justice Undone is to heal myself and to start to reclaim the visual history of African Americans in the United States.

My political awareness stemmed from my undergraduate studies. I was an American Studies major with a concentration in human rights. In my course work, which spans from American literature and history to sociology, I learned to recognize the complex weave of racial, economic, and political threads that form the social blanket of America. But, what really set me on this path was a senior seminar on the American Prison Industrial Complex. That class expanded my thinking on the subject, which later became my intellectual basis for the project.

PP: How did you decide on strategies to talk about these issues with your photography?

RTJ: There have been so many images about prisons and about the War on Drugs. A lot of the pictures work to reinforce stereotypes about minorities as “The Other.” In the first part of this project, I focused on children and families left behind in mass incarceration’s wake. I felt I had to avoid images of black men in the beginning because I did not want viewers from outside of these communities to immediately write the project off. I needed those viewers to move beyond the stereotypes and to have a empathetic reaction, without relying too heavily on people being portrayed as victims. In the next stages, I will focus more on the men, who are actually directly affected by prison.

Many of the great documentary photographers of the past three decades have produced work that is great but also problematic because they reinforce stereotypical images of urban black life. One of those photography books I have on my bookshelves in Eugene Richard’s Cocaine Blue, Cocaine True. It is an important work, but if you don’t dive into Richard’s words that were published along with the images you can come away with a skewed meaning. It is this decontextualization that worries me.

My strategy to combat this decontextualization is to create images of black life that focuses on the everyday. By searching for images that show African Americans in the mundane ritual of daily life, I hope that people not directly affected by mass incarceration will be able to see themselves in the pictures the way I do, as an antidote to years of self-hate and willful ignorance.

The Booker T. Washington Public Housing complex, in Austin, Texas, is plagued by a revolving door of single-parent households and incarceration.

Nicholas Brown, 19, speaks with his girlfriend before leaving. He has a stained relationship with his mother Vicky who has spent the majority of his childhood away in prison and drug treatment institutions.

Marquis, 18, BB and Leroy Brown hangout on the front porch of Beverly Brown’s house in Austin.

Tyler Pippillion works on a math puzzle during a skills class at the African American Men and Boys Harvest Foundation, a non-profit in Austin, TX that works with at-risk minority youth.

PP: What are the main points you want to communicate in your work?

RTJ: The first thing I hope my audience gain from this project is that U.S. laws have been unequally enforced in poor minority communities. Second, I wanted to make understood that the large numbers of men and women cycling in and out of prison has an immeasurably negative effect on their communities. Finally, I want the audience to realize that the impact of incarceration is falling on small geographic areas within cities, because a large portion of these men and women are being taken from identified communities.

PP: Can you explain the title ‘Justice Undone’?

RTJ: I think that justice and fairness are central to the American ideology. If you follow the rules you will be rewarded. If you break them then you will be punished. For African Americans, The Civil Rights Act of 1964, was “justice” for generations of discrimination and abuse. But, the gains of the 1960’s were essentially rolled back by the War on Drugs, the tough-on-crime movement, three strikes laws, and drug sentencing laws, which unfairly fell on the shoulders of African American communities.

So the title is meant to reflect the havoc of three decades of drug policies and the resulting explosion of the U.S. prison population that has played a big role on the agency and self esteem of African Americans in the United States.

I wanted the title to reflect critically on the U.S. justice system, which has failed to protect its most vulnerable members. While I was writing and reporting for my masters thesis, I was inspired by the hip-hop song Tip The Scale from the Roots’ album Undun.

Lot of niggas go to prison

How many come out Malcolm X?

I know I’m not

Shit, can’t even talk about the rest

Famous last words: “You under arrest”

Will I get popped tonight? It’s anybody’s guess

I guess a nigga need to stay cunning

I guess when the cops comin’ need to start runnin’

I won’t make the same mistakes from my last run in

You either done doing crime now or you done in

I got a brother on the run and one in

Wrote me a letter, he said when you comin’

Shit man, I thought the goal’s to stay out

Back against the wall, then shoot your way out

Gettin’ money’s a style that never plays out

‘Til you end up boxin’ your stash, money’s paid out

The scales of justice ain’t equally weighed out

Only two ways out, digging tunnels or digging graves out

Through the lyrics of this song, I felt the frustration of many black men who have limited choices, but still must navigate the challenges of being a black male in the United States.

A boys listen to instructions on keeping a proper boxing guard during a rally to protest the shooting death of Almeded Bradley by an Austin Police Officer.

Boys play a game of basketball in the Booker T. Washington public housing complex, Austin, Texas.

Teenage boys play basketball at the Youth Study Center juvenile detention facility in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Chelsea Shorts set up a studio in a shed in the backyard of her east Austin home. She uses the space to make clothes, draw and paint. The shed is a refuge from the crowded house that she shares with her parents, grandparents, cousins and one sibling. Chelsea biological father was incarcerated for most of her life.

Beverly Brown covers her eyes as she rest in her living room. Members of three different generation of her family have been incarcerated or had problems with drug addiction.

PP: Is there an easy way to describe the massive effect harsher sentencing and imprisonment has had on communities you’ve documented. How, in other words, do we put it into words?

RTJ:There is no simple way to discuss the topic because it is so complex.

A lot has been put in words, but I don’t know if we have reached the same level of understanding in the visual. Part of my goal is to reimagine the image of African Americans in Americans’ visual memory. These days there is always public outcry at any sort of overt racial discrimination in words, written or verbal. There is a bit of a lag in the public’s response to visual stereotypes of minorities. Responding to these stereotypes and creating what bell hooks, calls the “oppositional black aesthetic,” is a way that image makers can help challenge mainstream biases.

PP: What can we do as audiences to photography and as citizens to improve the situation?

RTJ: The next time they see a newspaper article or a television news report about a drug arrest or a drug sentencing I hope they start a conversation with a friend of family member about what is happening in their name as taxpayers. I want people to see beyond the individual situation and start to see the overarching pattern of crime, punishment, drugs, and incarceration in America.

PP: How do you describe photography’s role in relation to social justice?

RTJ: I don’t know if social justice can happen in a visual vacuum.

Photography’s first purpose is to pass information about an issue to an audience. Its second purpose is to move the social conversation past exposition. There are details in the everyday that offer unique paths to understanding.

PP: And empathy.

RTJ: From the expression of someone’s eyes, to the color of a summer dress, to the chaos of a kitchen before serving Thanksgiving dinner. It is in those common areas that we as human beings find ways to related to each other. Photography as a quasi universal medium is perfectly suited for this task.

PP: Thanks, Raymond. And thank you for your work and conscience.

RTJ: Thank you, Pete.

Chelsea Shorts walks alone railroad tracks in Austin, Texas. Shorts father was incarcerated for most of her life.

BIOGRAPHY

Raymond Thompson Jr. is a freelance photographer and multimedia producer based in Morgantown, WV. He currently works as a Multimedia Producer at West Virginia University. He received his Masters degree from the University of Texas at Austin in journalism and graduated from the University of Mary Washington with a BA is American Studies. He has worked as a multimedia photojournalist for the Door County Advocate, the Times of Northwest Indiana, the Kane County Chronicle, Times Community Newspapers and the Washington Times.

You can follow his activities on his blog, on the Twitter and on Instagram.

Children’s graffiti covers the walls of a cell at the Youth Study Center juvenile detention center in New Orleans, LA. The center serves as the pre-trial detention for youths charge with committing a delinquent offense.

Prison Obscura continues to travel. If you’re in or around New Jersey then you should know a version (a tighter edit) of Prison Obscura is currently on show at Alfa Arts Gallery in downtown New Brunswick. The show runs until November 1st.

The official opening was last Friday (10th) and coincided with the Marking Time: Prison Arts & Activism Conference at Rutgers University and hosted by the Institute for Research on Women (IRW). To give you a taster of the presentation, below are some snaps taken by staff at Alfa Arts Gallery. But not before a few notes of thanks …

GRATITUDE

I’d like to thank Alfa Art Gallery-owners Chris Kourtev and the entire Kourtev family for generously giving over their space for three weeks to house the show. Thanks to Nicole Fleetwood, Sarah Tobias and all the staff at IRW involved in bringing Prison Obscura to NJ. Thanks for a wonderful conference too!

I’d also like to extend my thanks once more to Matthew Callinan, Associate Director of Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford. Matthew continues to make sure the logistics for each venue are taken care of and, in this case, gave up an entire Sunday to drive from Philadelphia and install the show. Thanks to the staff at John B. Hurford Center for Arts & Humanities at Haverford, who continue to support the exhibition.

For more information about the exhibition, visit the Prison Obscura website.