You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

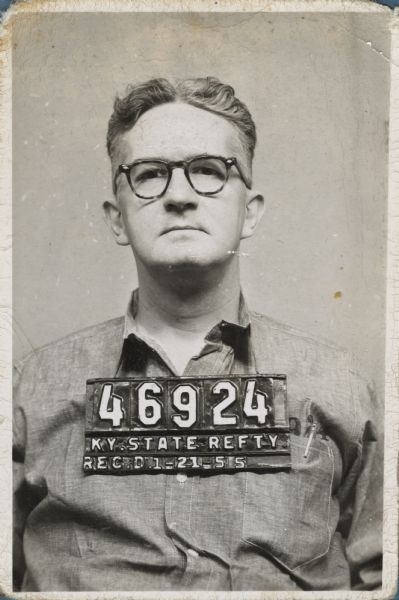

CARL BRADEN

I was surfing through the Wisconsin Historical Archives, like you do, and came across the above image of Carl Braden.

Braden and his wife Anne Braden were journalists-turned-activists who were part of the union movements and later the radical interracial left of the 40s and 50s. The Braden’s bought a house on behalf of the Wade family, their African American friends in suburban Louisville, Kentucky. When neighbours found out a Black family had moved in they burnt a cross outside the house and went after the Braden’s. Carl was charged with sedition in what is known as the Wade Case. Carl was sentenced to 15 years and served 8 months, eventually paying $40,000 to get out.

The Anne Braden Institute (ABI) now operates out of the University of Louisville. The ABI has a Flickr stream of scenes from her full life.

KARL BADEN

Karl Baden has chosen to put himself in the picture everyday for 24 years. Somewhere he has set up a self-imposed mugshot identification room. All these can be seen at his website Every Day.

It’s worth noting that Baden and Noah Kalina are the original and best for these vaguely masturbatory, mirrored versions of themselves in time-lapse. Others include a girl with a nice set of scarves, two dudes (one and two) with beard-growing missions, a guy with an 800 day commitment and Homer Simpson.

There is also Diego Goldberg who self-documents he and his family once a year, every year on the 17th June.

Baden has established a unique set of data for a limited case study in visual anthropology. The date runs like an I.D. number at the bottom of his shots.

As Baden describes the project, he removes emotion and variables from the photography, just as police or criminal justice photographers do for mugshots:

Every Day is performed within a set of guidelines. […] Reserved exclusively for this procedure are a single camera, tripod, strobe and white backdrop. […] I use the same type of high-resolution film (Kodak Technical Pan until it was discontinued in 2007, Ilford Pan F since then) and the same strobe lighting. The camera is always set and focused at the same distance. When taking the picture, I try to center myself in the frame, maintain a neutral expression and look straight into the lens.

Baden lists the key tenets of Every Day to be mortality; incremental change; obsession (its relation to both the psyche and art-making); and the difference between attempting to be perfect, and being human. I’ll grant him those things, but I also wonder is does the project not feel like a sentence?

And my question to you, readers, is what should we make of this type of project? It could be just inventive fun or it might be one of the most present-minded approaches to photography there is? I can’t decide.

© Dane Jones/Center for Employment Opportunities

What happens after incarceration? What does life look like; how does one operate? More to the point what does the world look like?

With the development of Released the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) in New York has tackled these queries with a multi-media-headed-hydra of photography and narrative.

Released “produced to offer a rarely seen perspective of those returning home from prison or jail” was set in motion by Cara Shih, Marketing Director at CEO. It consists of two parallel projects.

Firstly – to describe what life looks like – she contracted three young photographers to capture, produce and tell the stories of CEO’s clients as they left prison and built new lives.

Secondly – to describe what the world looks like – Shih enlisted CEO clients to self-document their re-assimilation into society.

The result are two very different sets of valuable works.

© Dane Jones/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Darryl Allen/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Darryl Allen/Center for Employment Opportunities

The main body of work for Released is the collection of nine slideshows of nine individuals (youtube/embeddable) by photographers Jeyhoun Allebaugh, Michael Scott Berman and Bryan Tarnowski. There’s no narration but the subjects’ own, and that’s everything that’s needed. These are real characters. Kudos to Allebaugh, Berman and Tarnowski for getting out the way of the stories.

It was Allebaugh who first contacted me about the project and so I fired him back a few questions. Before that, let me mention the second element of Released.

As you know though I have high expectations of prison arts education and the prospect of self-rehabilitation through photography, so when Allebaugh explained the ‘Snapshot Project’ within the Released project I knew I wanted images made by the six former prisoners on disposable cameras to feature here on Prison Photography. Allebaugh understood.

I speak more on ‘Snapshot Project’ after the Q&A.

JEYHOUN ALLEBAUGH Q&A

PP: How did you come across this project?

JA: Released was the brainchild of Cara Shih. She wanted to create an honest and genuine portrayal of the experience of her participants in a creative and artistic way.

PP: Had prison improved or set back the lives of the nine subjects you followed?

JA: Hmm. That is a difficult and complex question. While incarcerated, one of my subjects, Revond Cox, had to attend his son’s funeral in shackles and a DOC jumpsuit while his other young son sat graveside. I’m not sure any person should have to go through something like that. To call it a “setback” would certainly fall short. However, in his piece on the site, he says, “[prison] saved me from death because the way I was running, it was just a matter of time.” He clearly has his head on very straight about the type of father he wants to be and I do think some of that epiphany is directly related to his very difficult time in prison.

PP: Do you think the systems for employment, reintegration are fair for those formerly incarcerated?

JA: Life is extremely difficult for formerly incarcerated people coming home. The line between a new life and their old lives is razor thin and just as sharp. It is often much more complex than just coming home and doing right. Coming back to families and the stigma of finding a job as an ex-con make it very difficult. That said, I think organizations like the Center for Employment Opportunity are a very effective way to balance these things out, but many go without services such as these.

PP: What’s your biggest take away from the project?

JA: When we started this project, one of the key ideas behind Released was to show that when the formerly incarcerated come back home, it is often not to the “clean slate” that many of us imagine it to be. We wanted to show that there are new and different obstacles these people must face and I believe the project highlighted these well, showing some of the areas where the aid of an organization like CEO is imperative.

I believe what ended up being great about the project, however, was that more than the differences, the similarities between what the subjects and normal people go through on a day to day basis was what was most evident. I think this is what was really special about seeing photographs taken by the subjects themselves in addition to the ones we took as professional photographers.

The nine individuals we documented over three months are some of the best human spirits I have come across; absolutely amazing people. I hope you’ll spend a couple minutes getting to know them by watching the short videos on the site.

I’ve very much enjoyed staying in touch with these great people since the project. Listening to them talk about the continual triumphs and struggles of this great life we are given has truly been a gift and is a great inspiration to me.

© Jose L Padilla/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Jose L Padilla/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Jose L Padilla/Center for Employment Opportunities

‘SNAPSHOT PROJECT’, RELEASED, CEO

The snapshots are the daily details, daily grind and efforts and situations that don’t make it onto an outsider’s camera or off the cutting room floor. If Allebaugh et al. provided the over-arching narratives of empowerment and improvement, these are the chapters, pages and phrases.

As Allebaugh stated, the snapshots show off the same foibles we all have – Jose Padilla‘s fashion savvy, big smile and willingness to perform for the camera; Dane Jones‘ wonder with the street and his omission of self; Lewis Epps‘ focus on the activities, training and environments to keep him on track; Dwayne Allen‘s tourist shots of Manhattan’s Financial District; Chester Boston‘s preoccupation with portraiture and the family; and Michael Hunt‘s meanderings about his new or old neighbourhood.

Too often we can get caught behind the idea – and support of – a large goal without stopping to think about the many tiny, terrifying steps needed to achieve the goal. These images reveal those steps. Due purely to the equipment, the ‘Snapshot Project‘ is overlaid with naivety. But there is also good intentions, massively important small victories and the promise of networks that will help these men achieve a life outside prison permanently.

© Lewis Epps/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Lewis Epps/Center for Employment Opportunities

LEWIS EPPS ON LIVING IN A SHELTER, PHOTOGRAPHY, AND HIS MOTHER

If you want to know more about Lewis Epps, CEO has published a Q&A with Epps on their blog. Here’s my choice of quotes:

I was happy that I was doing [The Snapshot Project] and engaging in a project that would reflect my life. You know how you want to leave a legacy? I want people to say, “Yeah, Lewis he’s a good guy.” You know, I was doing something good to help me, and to help others, and also to be thankful to CEO for the opportunity.

I feel like I am ashamed to be in a shelter, I have never been in one my entire life. I had no place to live, so they released me to the shelter.

I have a tight, helpful family and we’re all very close. I lived in the Bronx, that’s where my criminal activities came from. My mother is elderly and I don’t want to bring that back to her … My family is very supportive. I go every Saturday to my mother’s to do painting, backyard, do work for her. Sundays I go to church.

I’m about to move from a shelter into a room of my own. I save my checks. I hide my money when I cash my checks, so I’m not tempted to spend it. I’ve been saving for three months since I started working and I’m almost ready. I also have family support. Finding a suitable place is tough. I can’t afford a room yet but I’m doing better than I’ve been in the past. I need a permanent job so I can retain my income and keep being able to afford a place of my own.

It stays in front of me, being re-incarcerated. Once I stop being good, I could be back. I’m too old to go back, I’ve got to move forward and think positive. CEO is helping me strive, and I know I’ve got to keep my focus. Once I don’t keep focus that could be it. One mess-up, that’s all it takes. I’m not going to do that again. I’m going to stay around people who are trying to help me.

Shih informs me a similar Q&A with Jose Padilla is next.

© Chester Boston/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Chester Boston/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Michael Hunt/Center for Employment Opportunities

© Michael Hunt/Center for Employment Opportunities

SNAPSHOT PROJECT PARTICIPANT-PHOTOGRAPHERS

Dane Jones, 26, lives in the Bronx with roommates. His challenges to re-entry include obtaining employment, education, financial management and housing. When asked what is the most challenging part of his daily life, he says “fitting in and conforming to the norms of society.”

Lewis Epps, 49, resides in a shelter. Currently he works on the transitional job sites while searching for permanent employment. His biggest challenges to re-entry are obtaining full-time work and permanent housing. He has a very supportive family who is helping him succeed in the re-entry process.

Darryl Allen, 46, lives in Queens with his father, brother and nephews. He has three daughters (including a pair of twins), and his eldest daughter is a lawyer. His biggest challenge to re-entry is obtaining employment. Darryl says the most challenging part of his daily life is “being a friend and father to my children.”

Chester Boston, 34, lives in Queens with his uncle. His biggest challenge to re-entry is obtaining employment. He has a five year old daughter, whom he named after his mother. He says fighting for custody is a daily challenge and not seeing her is very hard.

Jose L. Padilla, 47, lives in Brooklyn. After completing Life Skills Education and becoming Job Start Ready, he landed a full-time job and now comes to CEO for retention services. To him staying punctual is the most challenging part of his day. He has a certificate in construction.

Michael Hunt, 48, lives in Brooklyn. His biggest challenge to re-entry is finding stability in his life, and “being able to be myself and become employed at the same time.” His certificates include carpentry, electrical technician, fire guard and maintenance.

If you would like to hire CEO participants please contact Mary Bedeau at 212 422 4430 x345.

‘RELEASED’ PHOTOGRAPHERS BIOGRAPHIES

Jeyhoun Allebaugh is a freelance photographer who specializes in documentary, sports and portraiture photography. He is based in New York City and North Carolina. As a Turkish-American and avid fan of Hip-Hop and Bluegrass music who has spent his college years in the mountains of North Carolina as well as South Africa, Jeyhoun brings a diversity of taste to all aspects of his life. His work has appeared in GQ, PDN Emerging Photographer, USA Today, UK Guardian, SLAM Magazine, HOOP Magazine, The Durham Herald-Sun, The Durham Independent Weekly, NBA.com and SI.com.

Michael Scott Berman is a photographer specializing in food and portraits. His past clients include the New York Daily News, the Guardian, PNC Bank, and the AARP. He was the recipient of two grants from the Brooklyn Arts Council and has exhibited his work at the Leica Gallery in Manhattan and at Brooklyn Borough Hall. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in English from New York University and a Master of Business Administration from Georgetown University. Besides taking pictures, Michael also produces video and writes stories for his food blog, pizzacentric.com.

Bryan Tarnowski grew up in North Carolina and moved up to New York City to pursue photography in 2008. He assists with a number of the best fashion, commercial and portrait photographers in the world and has worked on shoots for top magazines and worldwide ad campaigns. Focusing on social documentary subjects of a wide variety, he likes to shoot what interests him, often to learn more about a subject and to quench his thirst for greater knowledge of the world. His work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Vibe Magazine, PDNedu among others.

Last month, Allebaugh, Berman and Tarnowski exhibited their work at the CultureFix Gallery on the Lower East Side. CEO has a Flickr set of the opening.

Chris Vernon takes a long shot in the recreation yard at SEPTA Correctional Facility. Basketball, volleyball and horseshoes are the only opportunities for physical recreation. © Victor J Blue.

VICTOR J BLUE

“What do we expect from people who go to prison? They broke the law, there was a process, they were punished, they got out. But what then?” asks Victor J Blue who’s just published Almost Out, a 4-month long reportage about SEPTA Correctional Facility in Nelsonville, Ohio. The report consists of a photo essay, a short video documentary, and a 4500 word written piece.

Blue describes SEPTA:

“Opened in 1990 to provide judges and sentencing courts in southeast Ohio an alternative to prison or probation for felony offenders, and to help convicts transition back into home communities. The idea is that locking guys up in a place where a battery of programs are not just available to them, but required of them—can cause a shift. It can change outcomes. They can learn to stop coming to prison.”

Corey Cunningham, George Fisher, and Doug Starcher, (left to right) talk with Jeff Johnson, (right) on the recreation yard at SEPTA. Prison gang affiliations and racial tensions that mark other prisons are less prevalent here. © Victor J Blue.

Blue, who is trying to build a portfolio of projects documenting and unpacking the criminal justice system, contemplates the difficult transitions and changes facing former prisoners, “They are felons now, and they will carry that distinction for good. I am interested in how guys getting out are marked, physically and psychologically, by their experience of incarceration, but do not want to be defined by it,” says Blue.

I’ve been aware of Blue’s work since he shot the b-roll for Ted Koppel’s Breaking Point (2007) about California’s overcrowded prisons. Blue consequently produced an award winning Best of Photojournalism essay in the ‘Non-Traditional Photojournalism Publishing’ category, 2009.

OHIO UNIVERSITY

Last week, I spoke about the impressive photography and multimedia work of Dustin Franz and Angela Shoemaker; both graduates of Ohio University’s School of Visual Communication, the same body that Blue and his fellow students are working within.

So, it’s high time we pay recognition to the professional output of the OU SVC student body; especially as it seems to be a leader in the production value of its material published online.

“We just finished our annual reporting project here at OU, it’s called Our Dreams are Different,” says Blue. “We are trying to build some audience for our stories. I don’t know if you are familiar with the project, but this years edition is much tighter and with better storytelling than years past.”

From the website, the approach of Our Dreams are Different is described thusly:

“The stories in this project examine the American Dream — how the dream has changed, how it persists, as well as the myths and realities of its unending pursuit. By telling these stories in the small towns of Southeast Ohio, our goal is to help folks better understand our communities, our neighbors and ourselves.”

BRAD VEST

Ohio University students are being noticed elsewhere too.

Today, DVAFOTO sung the praises of Brad Vest‘s project Adrift and ran a short interview with him about his process and access. Brad writes:

“This is a story about drugs, family and absence along a bend in the river. Travis Simmons is attempting to move past his addiction, and despite prison, parole, parents, and his devotion to his daughters, he cannot stay out of trouble.”

Photojournalism is dead? My arse.

Chris Vernon opens his locker, decorated with photographs of his family in his room. Residents wear pink shirts like the one Vernon has on when they have committed rule violations and they are restricted from furloughs and going outside on the yard. © Victor J Blue.

In an email, Dustin Franz explained that his project Finding Faith is about those who find spiritual direction “be it in any religion, while incarcerated”. It was made at the Marion Correctional Institute and documents the activities of the Horizon program, a multi-faith religious initiative.

Dustin asked what I thought, so here goes. There’s a couple of strong images in among the series. I’ve selected my two preferred photographs (above): they closely approximate to the eerie weight of both incarceration and organised religion.

Like most others, Dustin is probably not aware of my aversion to shots of receding tiers! Same goes for barbed wire. So we’ll scratch those two.

His shot of the chapel congregation is forgettable, but most B&W documentary shots are these days – that’s just the way percentages play out. His two group shots (one is below) are strong and show the connection, commitment and concentration ongoing between participants and volunteers.

The two shots of Muslims in prayer are indicative, but I wonder today if there’s a danger of stoking irrational fear by showing Islam in prison without conscientious background information? This is a reflection of my caution more than the photographer’s skill. If we are going to understand why any religions persist in prisons then we should start with a basic appreciation of their history. As a critic, I’m never satisfied.

The series is a nicely edited mixture of compositions, but I’m left feeling I need more. So often documentary photography describes the scene but doesn’t grip the emotions. Audio is a great complement, so kudos to Franz for producing the accompanying multimedia piece Hope is on the Horizon.

The narrated slideshow opens with this quote from Jeff Hunsaker, Horizon program coordinator, “If you stop and think about it, prisons today have become human junk yards. This is where we throw away the people we don’t want.”

Bang. Done. I’m hooked.

Quickly following Hunsaker’s words are those of a prisoner explaining that it is not about Christian bible-bashing (Horizon is billed as an ecumenical program) but about taking responsibility. Basically, as we all know, situations peered upon by journalists are often better described by the subjects than the reporters. Franz and his co-producer, Angela Shoemaker, were wise to adopt multiple media to tell the stories at Marion prison.

Dustin Franz is the photo editor for The Athens News. In the past, he has worked for The Aspen Daily News, Colorado. He’s the latest in a long line of budding photographers from the photojournalism program at The School of Visual Communication at Ohio University. Others include, of course, Angela Shoemaker (whose work I’ve pointed out before) and Maddie McGarvey who just won the LUCEO Student Project Award and took Dustin’s bio portrait. Dustin lives and works in Athens, Ohio and blogs here.

From the series Shelter by Henk Wildschut. From a shortlist of six photographers’ projects, Wildschut won the 20,000 Euro DUTCH DOC AWARD.

Last weekend was the Dutch Doc Festival.

The theme for this years Dutch Doc Festival is the slow type of journalism, which “focuses on long-term projects that frequently involve a strong personal commitment and steer clear of passing fashions. Projects that revisit a (pre-documented) subject in a sequel or to create a new sequence in follow-ups after set periods of time.”

Photoblogging duo Mrs. Deane were involved in the festivities and asked other bloggers and I to pitch in. They emailed:

To underline the relevance of the online community in shaping the contemporary debate, we would like to invite a number of what we consider ‘distinct voices’ to contribute to the festival via our presence. We would tremendously appreciate it, if you could select three photographic projects that you feel should be considered when discussing what’s needed right now, what people should be looking at, what has been forgotten, or what new projects are leading the way in the field of documentary photography (especially the kind that is also moving within the confines of the fine art galleries).

Ignoring the last criteria, I unapologetically picked three very political projects. Mrs. Deane posted my response over there, and I cross-post here for good measure.

THREE NEEDED PROJECTS

At a time when images rifle across our screens and retinas usually serving the purpose of illustration or corporate propaganda, the resolve of photographers to create bodies of work that deal with politics — and often large narratives too — can be read as either foolhardy or enlightened. I’ll pick the latter.

Kevin Kunishi’s work in Nicaragua, Joao Pina’s documentary in South America and Mari Bastashevski’s documents from Chechnya explore to varying degrees, “what has been forgotten.” Photography is art and art should be political. If we considered remembering and memory the first act in resistance against injustice then these three projects are high art.

From los restos de la revolucion © Kevin Kunishi

Kunishi’s Los Restos de la Revolution is a poignant look at the remains and the survivors of the Nicaraguan civil war. The portraits feature both former Sandanista rebels and former US-sponsored Contras. The mundane everyday details alongside deep psychological scars following conflict can be easy to turn ones back on when the bombs stop lighting up the skies. And it is easy to forget the US’s imperial policy and meddling in this conflict. One wonders if Afghanistan will ever have a cushion of a similar period of peaceful time to be part of a similar look back at the experiences and actions of its citizenry amid conflict.

From File 126 © Mari Bastashevski

Mari Bastashevski’s File 126 documents spaces previously inhabited by abductees who were “disappeared” during the Russian/Chechen conflict. Bastashevski says, “the abducted are incorporeal, as if they never were. They are no longer with the living, but they are not listed among the dead.” This is a particularly brave project given the state forces complicit in the departures are still in power and their reactions to Bastashevski’s inconvenient conscience are unknown.

From Operation Condor © Joao Pina

Joao Pina’s Operation Condor expansive work across South America, wants to both document and “provide evidence” for ongoing memory and trials into cases of of extrajudicial torture, kidnap and murder by the various Right-wing Military Juntas in South America during the 1970s and 80s. Like Nicaragua [and Kunishi’s work] the US had a strong influencing hand in either establishing or propping up many of these hardline governments. The crimes of thirty years ago are barely on the radar of the Western world however. How quick we forget! Pina is currently raising money for the next phase of his project at Emphas.is.

Colin and Joerg’s Selections

Mrs. Deane got a couple of other expert opinions.

Colin Pantall selected Third Floor Gallery, Timothy Archibald and Joseph Rock.

Joerg Colberg plumped for Brian Ulrich, Milton Rogovin and Reiner Gerritsen.

Warehouse District, Fresno, California © Matt Black

Last week, Stan blew the cover on my long held admiration of Matt Black. In the past couple of months, and on three different occasions, when conversation has moved toward photographers’ work that really turns us on I’ve begun explaining Matt’s work only to have the other person blurt out his name. You know that excitement when you’re on the same wavelength? Repeated.

Matt Black also has a great name. What else could he be but a photographer?

Matt’s documentary photography focuses on the social and environmental realities of southern and Central California, and the span of Mexico. Man-made borders need not apply. He’s knee-deep in the regions.

Each of Matt’s portfolios eddies of the last. It’s an admirable body of work. For his latest project, The People of Clouds, Matt has teamed up with Orion Magazine and Daylight Online for a cohesive distribution plan. He has also, for the first time, made use of Kickstarter for a very well-stated funding pitch.

Matt explains:

High in the Mixteca mountains of southern Mexico, an exodus is unfolding. In the birthplace of corn cultivation, where farmers first coaxed maize from the earth nearly 9,000 years ago, an ancient way of life is crumbling as land degradation and erosion cripple the soil and as migration tears families apart.

Named the “Place of the Cloud People” by the Aztecs, the Mixteca is home to one of the oldest and largest indigenous cultures in the Americas. Rugged and remote, the isolated region sheltered a pre-Colombian way of life that largely vanished from the rest of Mexico in the aftermath of the conquest. At its heart, it’s a culture of the land, and corn. Along the region’s hillsides, it is still possible to glimpse ancient terraces, canals, and runoff channels that protected the Mixteca’s rich but fragile soil, and nourished its inhabitants, for thousands of years.

But today, these ancient farming traditions have been lost, replaced by chemical fertilizers, hybrid seeds, and herbicides, the trifecta of modern agriculture heavily promoted in indigenous communities by the Mexican government and international charities as part of the “Green Revolution” of the 1960s. When combined with slash and burn farming, the Mixteca’s steep terrain, and the loss of other indigenous soil-preserving traditions like multi-cropping, these imported industrial agricultural techniques have turned Mixtec corn farming, one of the world’s oldest and most perfectly integrated agricultural systems, into a soil-eating machine.

Today, much of the Mixteca has been declared an “Ecological Disaster Zone,” the result of unchecked erosion, deforestation, and soil exhaustion. Per capita maize consumption is less than ten ounces per day, 90% below US rates, and fewer than a third of children under the age of five show normal growth by weight and height. Ranked on the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI), the Mixteca’s poverty is deeper than nearly all of Latin America’s, comparable only to areas of Africa, India, and the Gaza Strip. Far from sparking a Green Revolution, the industrial farming techniques prescribed to the Mixtecs have resulted in their becoming unable to even keep themselves fed.

Nearly a quarter million Mixtecs have emigrated to the US. Some villages have lost as much as 80% of their population and have become little more than ghost towns. “I only think about dying,” one elderly man told me. “My only worry is how my funeral will be.”

There’s a long and verbatim interview with my friend Bob Gumpert at Sojournposse. Salina Christmas and Zarina Holmes ask the questions.

Bob describes the arc of his work from labor to detectives to street cops to the courts to the jails. It’s a trajectory he has described to me before and it’s a lot to get hold of; I’m happy I wasn’t transcribing!

However, I’d never heard Bob tell this particular tale:

The rule was: “Ladies, I take a photo [of you], you tell me your story. Next week, I give you four photos.” Literally, I give them four photos. “And I put the CD in your property.” So that’s the way it works.

The women took the photos and sent them to their boyfriends in [other] jails. The prison didn’t like this. Why? I don’t know. It’s not a problem when the men down [the jail] do it. But when the women did it, it was a problem. Do I understand why? Do I make an issue out of it? No! But what happens? I get banned from the jail. Because the women did it.

So then I went back and I said: can we try again? The jail said yes. So long as they understand the rules…

So I said fine. I went back. And I explained all this: “I give you photos. You can send them home. But you cannot send them to the jail.” All the women said, “No problem, we understand.” They sent them home with instructions to send them to the jail. From home. Why? Because they weren’t sending them to the jail.

So, what happened? I got banned again. So I get back in and I said to the women, “You cannot send anything, any of these photos, in any form, from any place to the other jail.” And a woman raises her hand and said, “Can I have Xeroxes made of photos, instead?” And I said, no, you cannot. And I stopped going in. Because it was – at some point – if I kept going in, a problem.

UPDATED: Bob soon after returned to the jail to work with female prisoners.

I have often described photographs in prisons as emotional currency. The tenacity and single mindedness of these female prisoners is, to me, quite amusing. They’re resolute in how they want to use photographs, and the variant ways they circumnavigate an unenforcable rule trumps any analysis they make of the rule itself.

They’re just trying to connect … but it caused problems for Bob!

Another thing to negotiate when making photographs in sites of incarceration.

Bob Gumpert’s website Take A Picture, Tell A Story