You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

In 2004, Delmi Alvarez documented – over three days – the activities at Skirotava prison in Riga, capital of his adopted home Latvia. We discussed his motivations, the difficulties of access and human rights in Latvian prisons.

Q & A

Why did you decide to do a project inside a prison? Did you decide specifically on Skirotava?

For many years I’ve been interested in what happens inside prison walls. It was not the first time that I secured a permit to enter a prison.

I chose Skirotava because I live in Latvia and – through my work – I am an eyewitness to human rights [abuses]; Latvia is on the black list for its human rights.

I was working for SestDiena magazine. After many emails and calls, and with the help of the former chief editor Mrs. Sarmite Elerte, I got a permit. (Mrs. Sarmite Elerte, like many journalists and myself at Diena company newspaper, was made redundant).

My aim with the photo essay was to study the living conditions of [Latvian] inmates. After visiting Skirotava, I asked to visit more places but at the last moment my permit was denied. Many Latvian prisons don’t have good conditions. Simply, Latvians don’t care about that.

What sort of laws and attitudes exist within Latvia toward crimes, prisons and criminal justice?

I would prefer not to talk about that. I had many problems arise due to my opinions on this subject. In Latvia there is no freedom of speech.

Was it difficult to gain access?

You can imagine. From every direction, I faced questions – who I am; why I was interested; and what were my aims, etc.

But as I said earlier, Sarmite Elerte is a great person and she was always watching out for stories about humans rights. Without her letter of recommendation I would never have gained entry.

If you are trying to enter [Latvian] prisons at which human rights are under scrutiny, you are – for the authorities – like a spying enemy. Once you first enter, you must have a meeting with a few officials and they ask many questions.

This project happened in 2004. Perhaps things have changed today, but I didn’t have a good experience with the people that manage permits.

I would like to go back to give a lecture about photography to the inmates because they were very interested.

You’ve said that prisoners in your pictures are “children of dictatorship”. Can you explain that statement?

Many of them are from the times of Stalin, Soviet rule and KGB. Parents and grandparents of most inmates are from those times. Stalin was [seen as] a dictator by many Latvians.

In Latvia, the minority groups are called “aliens” and there are a large controversies over these minorities. I don’t really want to enter into these issues because it is not my country and Latvians need only study the issues and put things in order.

But something is real, Latvia is for Latvians and they are proud to fight for that. With that logic, they have good reason to want to manage their country before others, but there is an increase of extremism and nationalism. This is bad.

Many inmates come from remote poor areas in Latvia that survive without services. In these places, both Russians and Latvians live. Then, once in the prison, Russians and Latvians are not friendly and it is not a safe place for either group.

What ages are the prisoners? Where have they come from?

During my three-day visit, one officer had a talk with me in his office. He told me about the rules of my visit – no questions; no names; and no photos directly of the inmates without their permission.

In truth, I didn’t – don’t – want to know who they are and from where come from. Imagine … If I knew the person I was photographing was a rapist and killer, I wouldn’t be able shoot neutrally, I wouldn’t want to see into the eyes of the guy and I would be very affected.

I prefer that I don’t know about the person’s past. We are human. I know that many of them are children of drug addicts, alcoholics, and thieves. I know that they are not at fault being to born in this environment.

My question is: What can society and systems provide to help them find a way and be accepted? I am sure that there is lack of reentry programs in the prisons. In the US and other more developed countries there are programs like this. Why not in Latvia?

What reputation does Skirotava have to people for Riga and/or Latvia?

I have no idea, but when I said in a lecture that I had been inside, people looked at me as if they were looking at diabolo (sic).

What were the responses from staff and inmates to your work?

[During the visit] I was always with two officers and I wasn’t allowed to talk with inmates. The officers were not allowed to talk with me [about my work]. But, one inmate asked me to shoot a picture for his mother. With permission of an officer, I made a portrait for the [inmate’s] mother. This made me happy.

I wrote in the article that prisoners like novels and books. The next week, hundreds of novels, books and magazines arrived at the offices of SestDiena magazine!

Any animosity?

For the first visit, the editors assigned a writer to accompany me. Okay, we arrived, passed the check control, left matches, phones and all the stuff that you are not allow to carry inside. After that point we went to the secure areas of the prison – the real prison.

We went into a big empty yard, a big Comanche (sic) territory where hundreds of eyes are watching you: Who the hell are you boys? What are you doing here, cowboys?

One of the inmates approached the writer and told him something in Russian. After that the writer told me, “I am getting out of this fucking hell!” And I stayed alone. Later, I reported this to my editors and they said I needed to write the article myself.

Did you get a pair of gloves?

Yes! Absolutely. It was a big surprise. I have this pair of gloves at home. I saw one inmate making gloves and I asked him if it was possible to buy a pair. The guy didn’t answer me because an officer was near. Later, my translator said that the inmate would make me a pair. I received the gloves some time ago and I asked to pay, but the translator told me, “They are waiting for you to talk about photography [as payment]”. I never got that permit to return. I am sorry about that.

Thanks Delmi.

Thanks Pete.

BIOGRAPHY

Delmi Alvarez (1958-) grew up in Vigo, Galicia, northwest Spain. He has worked as an electrician, street nightclub-ticket seller, bartender, gardener to support his studies. In London, as a photojournalist, he contributed to AP, AFP and Reuters agencies. In 1991 spent one year in Cuba working in a documentary project about the life of the Cubans. From 1990 till 1993 he covered the Yugoslavia war as correspondent and photographer with La Voz de Galicia newspaper. The experience shaped his personal opinion about conflicts and following the deaths of friend-photographers Alvarez no longer cover conflict zones. Since the mid-nineties, Alvarez has worked on a long term documentary project Galegos na Diaspora documenting the spread of Galician people across the globe. The project has taken him to every continent. In 2006 the Galician Government invited Alvarez to develop a photographic project documenting and promoting the ancient pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela. Alvarez is currently working on projects with Magnum photographers Ian Berry and Richard Kalvar. Alvarez has lived among the Galician diaspora in Riga, Latvia since 2002. http://www.delmialvarez.com/

I was first aware of João de Carvalho Pina‘s work a couple of years ago when Jim pointed to Pina’s photographic homage to the political prisoners of Portugal (1926-1974). Two of Pina’s grandparents were imprisoned by the Portuguese regime.

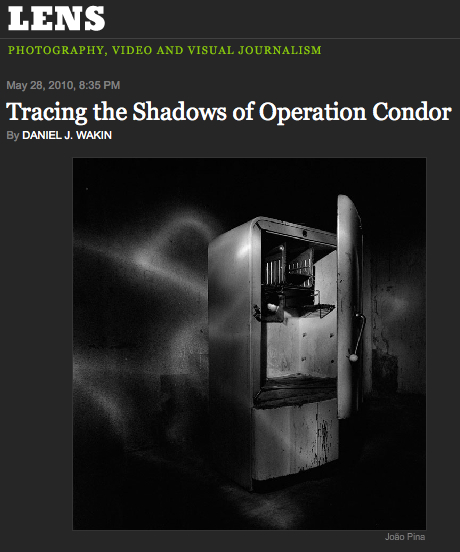

Just as that terror ended in Europe, another began across six countries in South America. Pina’s project Operation Condor has just featured on the New York Times’ Lens blog, for which Daniel J. Wakin explains:

“Operation Condor was a collusion among right-wing dictators in Latin America during the 1970s to eliminate their leftist opponents. The countries involved were Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay and Bolivia.”

More from the NY Times on the sites of detention:

Mr. Pina said he was struck by how ordinary the locations were — garages, a sports stadium, offices. “Most of them are places that can be in the corner of our houses,” he said. “They’re very normal places”

Very important work, not least the portraits of survivors. Pina’s goal is to create a visual memory of the era working against a relative dearth of historical documentation, “to show people that this actually happened. There are hundreds of thousands of people affected by it.”

The first four chapters of Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine deal with the military juntas and international interference in South America from the mid 50s until the 80s. Highly recommended.

– – – –

I have been working on a series of posts about the Desaparecidos in Argentina specifically, one group of nationals affected by the continental ideological wars of South America in the 70s and 80s. Expect follow up posts on this subject.

ELSEWHERES

Pina works on incredible breadth of issues, all related by their focus on the harshest of social violence. Most recently, his work on the gangs of Rio de Janeiro has garnered attention, here and here.

Below is an image from his Portuguese political prisoners project (source).

Update (3.30pm): Haeberle was not a journalist. He was an enlisted, unarmed soldier. He carried a camera instead of a gun. His orders were to photograph for Stars and Stripes, the US Army’s (propaganda) publication. On the day of the My Lai Massacre he had his military-standard camera, but also carried (smuggled) his own camera.

I found this quote in Part Exposé, Part Cover-Up: 1968’s My Lai Massacre Photos Have Big Lessons For Citizen Journalists a highly recommended article written by David Quigg for the HuffPost.

Drawing on the well circulated Plain Dealer article of last November, Quigg discusses how Haeberle controlled, destroyed and released his photographs of the My Lai Massacre; how the Army campaigned against the release; how he (Quigg) as a journalist and we as viewers should regard Haerberle’s embedded activity in the US military; and what implications this has for (self) censorship but also propaganda in the age of citizen-publishing. Quigg:

“Citizen journalists must not do today’s equivalent of what Haeberle did. Citizen journalists must not give in to the urge to un-take a photo, to click delete and banish the evidence for the parts of a story that shame them. In citizen journalism, we might as well rename the delete button and think of it as the “cover-up button.”

Click on the image above or go here to see images of Cleveland’s Plain Dealer coverage of the 1969 exposé.

© Kevin Miyazaki

Last year, I met Kevin Miyazaki. I told him of my project at Prison Photography and he told me off his recent project Camp Home.

Before I deal specifically with Kevin’s personal project of insistent history, let me briefly set some context for thinking about photography as it relates to WWII Japanese internment. Kevin and I discussed the well known photographers who visited the internment camps in California – Clem Albers, Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams.

“Richard Kobayashi, farmer with cabbages, Manzanar Relocation Center, California.” Ansel Adams, photographer. Photographic print, 1943. Reproduction numbers: LC-USZC4-5616 (color film copy transparency); LC-A35-4-M-31 (B&W film negative)

Adams’ was often criticised for his seemingly apolitical – almost bucolic – images of internees. The accusation was that Adams made the place look like a site of vacation and not of incarceration; this was a criticism I held too … until I met Kevin.

Kevin explained that Adams purposefully avoided depicting the internees as victims; Adams knew his (government-assigned) photographs would reach a large population, and into that population internees would eventually return. Adams’ intention was to protect, promote – even elevate – the dignity of his subjects.

One astonishing fact from this era, is that over two thirds of internees were American citizens.

Kevin and I also talked about Andrew Freeman, Mark Kirchner (both dealing with Manzanar) and the late and great Masumi Hayashi.

CAMP HOME

During WWII, at the age of thirteen, Miyazaki’s father was interned at Tule Lake in the Klamath Basin, CA, just shy of the Oregon border. Kevin work deals with the physical and domestic remains of that historical moment and movement:

“The barracks used to house Japanese and Japanese American internees were dispersed throughout the neighboring landscape following the war. Adapted into homes and outbuildings by returning veterans under a homesteading movement, many still stand on land surrounding the original camp site. In photographing these buildings, I explore family history, both my own and that of the current building owners – this is physical space where our unique American histories come together. Because photography was forbidden by internees, very few photographs of homelife were made by the families themselves. So my pictures act as evidence, though many years later, of a domestication rarely recorded during the initial life of the structures”, explains Miyazaki.

Well, I’d like to share with you a few Library of Congress images (1, 2, 3 & 4) I located on Flickr.

Japanese-American camp, war emergency evacuation, [Tule Lake Relocation Center, Newell, Calif. 1942 or 1943] 1 transparency : color. Collection: Library of Congress.

While looking at these Russell Lee attributed photographs consider these words about Miyazaki’s Camp Home by Karen Higa, Adjunct Senior Curator of Art at the Japanese American National Museum, wrote:

“President Franklin Roosevelt Delano Roosevelt ignored his own administration’s intelligence and in February 1942 issued Executive Order 9066, a presidential decree that paved the way for the largest mass movement of civilians in modern American history. Initially Japanese Americans were forbidden from living in western coastal regions; weeks later the US government began moving more that 110,000 civilians into temporary detention centers and finally to permanent camps. Over 700 government issued barracks were constructed o the dry lake bed at Tule Lake creating what amounted tot he largest population in a region of wind-swept sage brush.”

“The people that settled in Klamath after the war may not bear the specific responsibility of incarceration, but they share a generalized sense that something happened. their homes have a prior life worth recognizing.”

Japanese-American camp, war emergency evacuation, [Tule Lake Relocation Center, Newell, Calif. 1942 or 1943] 1 transparency : color. Original caption card speculated that this photo was part of a series taken by Russell Lee to document Japanese Americans in Malheur County, Ore. Re-identified as Tule Lake because of similarity to LC-USW36-789, which shows Abalone Mountain. Title from FSA or OWI agency caption. Photo shows eight women standing in front of a camp barber shop. Transfer from U.S. Office of War Information, 1944.

Japanese-American camp, war emergency evacuation, [Tule Lake Relocation Center, Newell, Calif. 1942 or 1943] 1 transparency : color. Original caption card speculated that this photo was part of a series taken by Russell Lee to document Japanese Americans in Malheur County, Ore. Re-identified as Tule Lake because of similarity to LC-USW36-789, which shows Abalone Mountain. Title from FSA or OWI agency caption. Photo shows eight women standing in front of a camp barber shop. Transfer from U.S. Office of War Information, 1944.

Japanese-American camp, war emergency evacuation, [Tule Lake Relocation Center, Newell, Calif. 1942 or 1943]. 1 transparency : color. Original caption card speculated that this photo was part of a series taken by Russell Lee to document Japanese Americans in Malheur County, Ore., and showed people transplanting celery. Re-identified as Tule Lake because of similarity to LC-USW36-789, which shows Abalone Mountain. Title from FSA or OWI agency caption. Transfer from U.S. Office of War Information, 1944. Repository: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Part Of: Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Collection 12002-55 (DLC) 93845501.

ELSEWHERES

It’s uncanny how the internet works sometimes. This image was the subject of some debate over at the Oregon State University Flickr Commons archive. Unsurprisingly, Kevin’s work was noted and praised there too.

KEVIN

As well as an excuse to wade through the various photographic approaches to Tule Lake internment camp, this post was to bring attention to Kevin’s ongoing contributions to the photo community. Kevin extends his teaching beyond his Milwaukee classroom and does us all a service by listing the interviews he serves up his class, on the class blog. Last week, Flak Photo called out for some more suggestions to the pile.

Kevin also launched collect.give last year which offers choice prints by respected photographers for prices no-one can quibble. All proceeds to good causes.

– – –

Kevin J. Miyazaki (b. 1966, USA) is a freelance editorial and fine art photographer based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He began his career on the staff of The Cincinnati Enquirer, and later became the photography director at Cincinnati Magazine. He went on to become the photographer at Milwaukee Magazine. His publication credits include, Time, Newsweek, Forbes, Fortune, National Geographic Traveler and numerous others. He is represented by Redux Pictures.

Gary King, Computer Technician, Disabled. “Over the last eight years, these two plates are the only family memories I have left. Only by the Grace of God have I been able to hang onto them. They’re hand painted. I believe that both of these plates were done by my dad’s mom. The one I especially wanted to hang onto was especially done for me. It was stolen when the storage unit got busted into.”

– – –

Daylight Magazine granted us sneak preview of Susan Mullally‘s upcoming book What I Keep: Photographs of the New Face of Homelessness and Poverty, by way of Elin o’Hara Slavick’s introduction.

o’Hara Slavick says:

“Susan Mullally’s unforgettable color photographs of people who gather together in their “Church under the Bridge of I-35″ make visible something we usually choose not to see. There is a young woman holding a photograph of her sweet baby girl with whom she cannot live because she does not have a place to live. There is a picture of an African-American woman holding her Junior High School diploma. This is the first time the woman has ever shown it to anyone. There is an unemployed carpenter who collects any stuffed animal that he finds so he can give them to the children he encounters during his homeless days.”

and,

“Mullally respects her subjects, many of whose lives are constantly disrupted by serious challenges such as homelessness, incarceration, drug addiction, alcoholism, mental illness and poverty. Mullally simply asks each person what he or she keeps and why it is valued and she makes a color photograph of them holding that object of subjective value.”

– – –

What I Keep: Photographs of the New Face of Homelessness and Poverty, Susan Mullally is published by Baylor University Press and due for release Summer, 2010

Prison Valley, a documentary by David Dufresne & Philippe Brault, is a haunting view of a one of America’s greatest distopias.

From the introduction: “Welcome to Cañon City, Colorado. A prison town where even those living on the outside live on the inside. A journey into what the future might hold.”

16% of the Cañon City population is inside prison; it is an economy based almost entirely upon incarceration.

Cañon City has a population of 36,000 and 13 prisons, one of which is Supermax, the new ‘Alcatraz’ of America. The new Supermax was described by former warden, Robert Hood, as “a clean version of hell.”

The introduction to the documentary can be a little off-putting at first. The dramatic voice-over deals in emotive-speak and apparent hyperbole. But then you realise that the presentation is not an exaggeration – that the voice-overs are only shocking because of the underlying immutable facts.

Perhaps, as outsiders, French filmmakers Dufresne & Brault are the perfect artists to bring focus upon the most forsaken branch of America’s prison industrial complex?

WEB DISTRIBUTION

As well as taking on old(ish) prison subject matter in a new way, Prison Valley is purposefully designed as a web based project and “Web Documentary”. To view the film beyond its introduction you must sign in with either your Twitter or Facebook social network accounts.

Once signed in the website will bounce you between a mixture of multimedia, interviews, photo-galleries, non-sequitur video clips and auxiliary documents.

The documentary canvases opinion from various characters who the filmmakers meet along the way. The entire project is punctuated with the use of DVD-special-featuresque snippets. You can even attend a memorial ceremony for dead correctional officers.

BLOG

Prison Valley blog here.

Frank Schershel. Photos licensed for personal non-commercial use only by LIFE

I was made aware of this set of photographs last week (sorry I forget the source!). They’re an interesting document of a bustling metropolis’ prison with an open program of movement, activity and an array of inmates.

The number of visitors and family members involved in many of the images leads me to think of this prison as an institution where people remained until the peculiarities of their situation could be agreed upon and then communicated to ensure release.

The social engagement of inmates with those from outside suggests to me (with an acknowledgement of harsh lockdown-modern-prisons) that the authorities of 1950s Mexico City either weren’t convinced of prisoners guilt, could be convinced otherwise, or simply didn’t map the denial of family-involvement on to the landscape of criminal punishment.

Frank Schershel. Photos licensed for personal non-commercial use only by LIFE

Frank Schershel. Photos licensed for personal non-commercial use only by LIFE

Schershel’s photographs recalled Richard Ross‘ image from Architecture of Authority. Schershel’s images doubled my visual knowledge of Mexican prisons, and so know I find myself in the unacceptable position that Mexican penitentiaries are – in my mind (at least temporarily) – the Palacio de Lecumberri … which means I have to do more research to get away from that inadequate knowledge base.

Palacio de Lecumberri (former prison) Mexico City, Mexico 2006. © Richard Ross

Until Schershel’s photo set, I had thought that Ross’ picture depicted a tower in the centre of a modestly-sized jail, but Schershel’s image puts the tower and rotunda into its larger setting (top left octant).

Frank Schershel. Photos licensed for personal non-commercial use only by LIFE