You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Historical’ category.

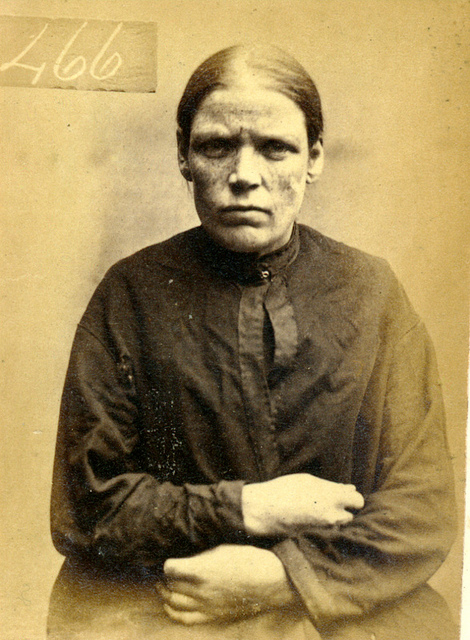

Catherine Flynn was sentenced to 6 months at Newcastle City Gaol for the conviction of the crime – stealing money from person. Age (on discharge): 34; Height: 5.1; Hair: Brown; Eyes: Blue; Place of Birth: Ireland; Status: Married.

Courtesy of the Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, there’s an absolutely beautiful set of portraits of criminals from the early 1870s in Newcastle, England.

This incongruous bunch is made up of men and women; young and old. Most have been sentenced to short-terms for theft of items (in most cases) necessary for survival – including boots, trivets, chickens, tobacco, oats, beef, or, in one case, four rabbits.

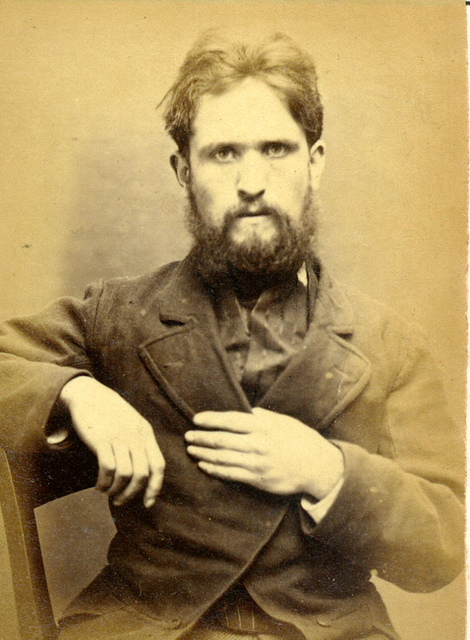

The portraits, which date from 1871-1873 are posed with much intention. Usually, the sitter rest a forearm on the chair back and sits with clasped hands. Sometimes they grip the lapels of their coat. All eerily poised.

John Richards was convicted of the crime – stealing money from person and was sentenced to 3 months at Newcastle City Gaol. Age (on discharge): 25; Height: 5.5½; Hair: Brown; Eyes: Blue; Place of Birth: Plymouth; Status: Single; Occupation: Hatter

This set of portraits remind me a lot of the well-circulated and well-loved portraits of criminals from the archives of the Police and Justice Museum, Sydney Australia. When I posted about them in January, 2011, I pointed out the obvious fact that they went beyond the sole purpose of identification one expects of police photography; Portraits, Not Mugshots.

When Alec Soth reflected on their quality and his constant search for excellence, he remarked, “I once again wonder why I bother with photography. It seems unfair that an anonymous police photographer can be as good as Avedon and Arbus.” Alien, and teasingly inaccessible, these portraits from Newcastle hold a similar power over the viewer.

In occurs to me, antique photographs allow us to distantly gawp toward ‘the other‘ – and precisely because they are ‘the other’. We can do this with more-or-less impunity and without the ethical problems of objectifying those in the photographs. I presume this is because the people are dead and the era is gone? There’s next-to-no political fallout for lazy interpretation of this century-old ‘other’?

Compare this to the politically fraught task and responsibility of gazing over photographs of other cultures in contemporary society. ‘The other’ is reinforced and made safe by the passing of time. However, ‘the other’ separated not by time, but only by space in our world today is very problematic.

Just something to think about, but not to taint your enjoyment of this dusty, eye-feast of portraiture.

Jane Farrell stole 2 boots and was sentenced to do 10 hard days labour. Age (on discharge): 12; Height: 4.2; Hair: Brown; Eyes: Blue; Place of Birth: Newcastle; Married or single: Single.

Also know as James Darley, at the age of just 16, this young man had been in and out of prison, but on this occasion he was sentenced for 2 months for stealing some shirts. Age:16; Height: 5.0; Hair: Brown; Eyes: Hazel; Place of Birth: Shotley Bridge; Work: Labourer.

MUGSHOTS

Elsewhere on Prison Photography:

In Joliet, Fine Art Photographers Have Got Nothing on Anonymous Inmates

Who Owns the Rights to A Mugshot?

HAT TIP

Thanks to Aaron Guy, curator for the photography collection of The North of England Mining Institute, for the link. Here’s Aaron sharing some of his discoveries [1], [2] in the archives on his personal blog, and here’s his @AaronGuyUK Twitter account.

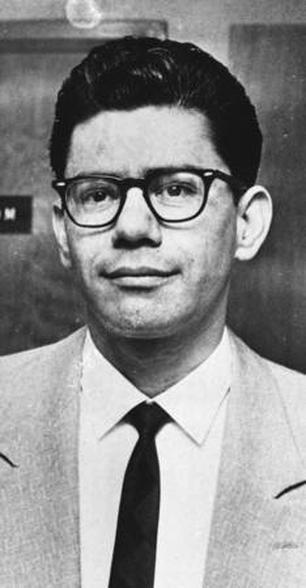

UPDATE: It just occurred to me that Ernesto Miranda looks like a young Al Franken.

Ernesto Miranda

Huh. I never realised Miranda Rights were named after someone named Miranda. And, if I had been shown a photograph, I’d have expected a female. Same applies for other renowned names. Say what do Roe or Wade look like? Or the Lovings? Or Brown, from Brown vs. Board of Education?

LIFE.com has a gallery of Faces Behind Famous Court Cases. From slide two:

Miranda v. Arizona, 1966. In 1963, police in Phoenix, Arizona, arrested career criminal and predator Ernesto Miranda (above) on charges of kidnapping and raping a young woman. Miranda was interrogated at the police station; without being advised of his right to representation and without being warned of his right against self-incrimination, Miranda signed written confessions and, at jury trial, was found guilty and sentenced to 20 years on each charge.

The issue before the Court: Were Miranda’s constitutional rights to representation and against self-incrimination violated by officers’ failure to apprise him of those rights? The decision: In a 5-4 ruling, the Court decided in Miranda’s favor. Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing for the majority, declared: “The warning of the right to remain silent must be accompanied by the explanation that anything said can and will be used against the individual in a court of law…”

One June 16th, 1944, the United States executed a 14 year old boy. His name was George Junius Stinney Jr.

There is good reason to believe Stinney’s confession was coerced, and that his execution was just another injustice blacks suffered in Southern courtrooms in the first half of the 1900s.

More from SC crusaders look to right Jim Crow justice wrongs, by Jeffrey Collins for The Associated Press (Jan. 18, 2010)

The sheriff at the time said Stinney admitted to the killings, but there is only his word — no written record of the confession has been found. A lawyer with the case figures threats of mob violence and not being able to see his parents rattled the seventh-grader.

Attorney Steve McKenzie said he has even heard one account that says detectives offered the boy ice cream once they were done.

“You’ve got to know he was going to say whatever they wanted him to say,” McKenzie said.

The court appointed Stinney an attorney — a tax commissioner preparing for a Statehouse run. In all, the trial — from jury selection to a sentence of death — lasted one day. Records indicate 1,000 people crammed the courthouse. Blacks weren’t allowed inside.

The defense called no witnesses and never filed an appeal. No one challenged the sheriff’s recollection of the confession.

“As an attorney, it just kind of haunted me, just the way the judicial system worked to this boy’s disadvantage or disfavor. It did not protect him,” said McKenzie, who is preparing court papers to ask a judge to reopen the case.

Stinney’s official court record contains less than two dozen pages, several of them arrest warrants. There is no transcript of the trial.

RESOURCES

Sound Portrait: George Stinney, Youngest Executed (2004)

When Killing a Juvenile was Routine

Too Young To Die: The Execution of George Stinney Jr. (1944) in Ch. 5, ‘South Carolina Killers: Crimes of Passion’, by Mark R. Jones.

From the series Shelter by Henk Wildschut. From a shortlist of six photographers’ projects, Wildschut won the 20,000 Euro DUTCH DOC AWARD.

Last weekend was the Dutch Doc Festival.

The theme for this years Dutch Doc Festival is the slow type of journalism, which “focuses on long-term projects that frequently involve a strong personal commitment and steer clear of passing fashions. Projects that revisit a (pre-documented) subject in a sequel or to create a new sequence in follow-ups after set periods of time.”

Photoblogging duo Mrs. Deane were involved in the festivities and asked other bloggers and I to pitch in. They emailed:

To underline the relevance of the online community in shaping the contemporary debate, we would like to invite a number of what we consider ‘distinct voices’ to contribute to the festival via our presence. We would tremendously appreciate it, if you could select three photographic projects that you feel should be considered when discussing what’s needed right now, what people should be looking at, what has been forgotten, or what new projects are leading the way in the field of documentary photography (especially the kind that is also moving within the confines of the fine art galleries).

Ignoring the last criteria, I unapologetically picked three very political projects. Mrs. Deane posted my response over there, and I cross-post here for good measure.

THREE NEEDED PROJECTS

At a time when images rifle across our screens and retinas usually serving the purpose of illustration or corporate propaganda, the resolve of photographers to create bodies of work that deal with politics — and often large narratives too — can be read as either foolhardy or enlightened. I’ll pick the latter.

Kevin Kunishi’s work in Nicaragua, Joao Pina’s documentary in South America and Mari Bastashevski’s documents from Chechnya explore to varying degrees, “what has been forgotten.” Photography is art and art should be political. If we considered remembering and memory the first act in resistance against injustice then these three projects are high art.

From los restos de la revolucion © Kevin Kunishi

Kunishi’s Los Restos de la Revolution is a poignant look at the remains and the survivors of the Nicaraguan civil war. The portraits feature both former Sandanista rebels and former US-sponsored Contras. The mundane everyday details alongside deep psychological scars following conflict can be easy to turn ones back on when the bombs stop lighting up the skies. And it is easy to forget the US’s imperial policy and meddling in this conflict. One wonders if Afghanistan will ever have a cushion of a similar period of peaceful time to be part of a similar look back at the experiences and actions of its citizenry amid conflict.

From File 126 © Mari Bastashevski

Mari Bastashevski’s File 126 documents spaces previously inhabited by abductees who were “disappeared” during the Russian/Chechen conflict. Bastashevski says, “the abducted are incorporeal, as if they never were. They are no longer with the living, but they are not listed among the dead.” This is a particularly brave project given the state forces complicit in the departures are still in power and their reactions to Bastashevski’s inconvenient conscience are unknown.

From Operation Condor © Joao Pina

Joao Pina’s Operation Condor expansive work across South America, wants to both document and “provide evidence” for ongoing memory and trials into cases of of extrajudicial torture, kidnap and murder by the various Right-wing Military Juntas in South America during the 1970s and 80s. Like Nicaragua [and Kunishi’s work] the US had a strong influencing hand in either establishing or propping up many of these hardline governments. The crimes of thirty years ago are barely on the radar of the Western world however. How quick we forget! Pina is currently raising money for the next phase of his project at Emphas.is.

Colin and Joerg’s Selections

Mrs. Deane got a couple of other expert opinions.

Colin Pantall selected Third Floor Gallery, Timothy Archibald and Joseph Rock.

Joerg Colberg plumped for Brian Ulrich, Milton Rogovin and Reiner Gerritsen.

The funeral of Horacio Bau a montonero militant from Trelew in the Argentine patagonia. He disappeared in La Plata in November 1977. His remains were found and buried nearly 30 years after. © João Pina

About this time last year, LENS blog featured João Pina’s ongoing project Operation Condor (since renamed Shadow of the Condor). Daniel J. Wakin wrote, “Operation Condor was a collusion among right-wing dictators in Latin America during the 1970s to eliminate their leftist opponents. The countries involved were Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay and Bolivia.”

João Pina has broken up those six countires into three segments and is currently raising funds via Emphas.is to complete the first focusing on Brazil.

Pina has already interviewed victims and families in Brazil:

In Recife in northeastern Brazil I interviewed and photographed Elzita Santa Cruz, a mother of ten who is now 97 years old. In 1964, when Brazil’s military dictatorship began, several of her children were arrested for political reasons on different occasions. In 1974, one of them, her son Fernando, became Brazil’s first politically “disappeared” person. Since then, Elzita has been demanding that the Brazilian authorities open their archives and explain what happened to Fernando and the other victims of the twenty-one-year dictatorship.

Having worked across South America for six years already, Pina will, as he intends, be able to create a “visual memory”, but as for making evidence for “use by a number of human rights organizations which are still trying to bring those responsible for Operation Condor’s repression to justice,” well, that’s an ambitious goal. Nevertheless, as a documentary project the subject is ranging and imperative. Good luck to him. I’ve stumped up some cash, so should you.

See the Emphas.is project page for Shadow of the Condor and see Pina’s video pitch.

The title for this post comes from Dostoevsky’s famous 1862 novel House of the Dead. The book is full of imagery of malnourished, edgy prisoners who are corralled through the harsh drudgery of the Siberian prison camp. For me, it is almost impossible not to think of Dostoevsky’s bleak interment when looking at photographs from Russian prisons. Much of the imagery I’ve seen from the former Soviet bloc (Als, Alvarez, Atwood, Krauss, Nachtwey, Vasiliev, Payusova) has depicted cold, hardened wretches. This may or may not reflect reality, but here I want to emphasise the prevalence of this type of imagery.

All photographs here in this post are by Sebastian Lister. I’ve taken the liberty to feature a small portion of his images and I’ve peppered them between famous etchings and paintings from art history to illustrate the persistence of marching, ordering, misery and boredom in prison imagery. America, Germany and England all feature in the historical images so we can acknowledge that this type of treatment and mood has existed in prison systems across the world.

Could it be that Russian prisons are persistently depicted as backward, brutal and stuck in the past? Is this the reality?

If you’ve not guessed, I’m setting something up here. I posit that, sometimes, these types of photographs are what we expect. Tune in on the blog later today to see a contrasting view.

Screen-grab from ABC newsreel footage, as featured in the Guardian‘s front-page slide show.

Osama bin Laden wasn’t in mountain caves. He was in a mansion in Abbottabad, a major Pakistan city two hours north of the country’s capitol, Islamabad. Bin Laden had been there for more than six months.

Part evil-lair, part self-imposed prison, part luxury – the mansion is a major part of the story and questions about “who protected Osama bin Laden over the past decade” will no doubt follow.

There’s a few things going on here, so let’s start with the most simple. “You made you bed, now you must lie in it die in it.” Anyone? No? (To be clear, I don’t know if this was OBL’s bed, or even if he was killed in this room).

Nonetheless, the blood on the floor tells us this bedroom is a site of ambush; the bed is an object of a stormed house. Yet, this image is not distinguishable in any meaningful way from all the other images of house raids in America’s 21st century wars.

THE VISUAL CULTURE OF BEDS

Contemporary concerns have been about sex (the discarded condoms of Tracey Emin’s My Bed proved her as honest as she is crass) and violence (or maybe Rauschenberg was just about disorder?)

Historically, the image of the bed has been co-opted for highly political purposes. And interestingly, the bed played a central role in the dissemination of images of Arabic regions round Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Artists under patronage painted aristocracies, noble beasts, mythologies, and Christian narratives. The boudoir was rarely mentioned; acts of the bedroom hidden. For titillation, commissioned artists were sent abroad. Orientalist Art has little to do with the distant lands it “depicts” but most to do with the obsessions of artists and patrons with harems and the sexual behaviours of people of colour.*

Without wanting to over-simplify, Orientalist Art is – at both conscious and subconscious levels – the projection of suppressed sexual desire upon an “Other” group. The subject has little or no means to correct the misrepresentations. Furthermore, any corrections by the subject would disrupt the self-serving narratives of the distant audience.

Centuries of visual manipulations and stubborn visual usury between the West and the rest, with the bed as the visual anchor to the lazy indifference, are wrapped up in the unorthodox war photograph above. If the image does indeed depict the bed of Osama bin Laden (the personification of cultural antagonism, violent opposition, the most distant of “Others”) then, I at least, identify some irony therein.

“The Siesta,” by Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928), oil on canvas, 11 ¼ by 17 inches, 1878, private collection, courtesy of the Spanierman Gallery, New York

One final thing. A bed is a place of rest, a grave is a final resting place. Western allies worried any grave would become an extremists’ pilgrimage site, so Osama bin Laden’s body was buried at sea. But have they avoided the problem? Might this Abbottabad mansion and this bedroom not become places of pilgrimage?

*Orientalist Art tends to refer to North Africa, but includes South Spain and the Middle East. The fetishisation of women of colour was also foisted upon Native people in North America and across the British colonies of the Southern Hemisphere.

Born: November 27, 1932; Philadelphia; Arrested July 30, 1961; Train station, Jackson; Then: Student, Santa Monica City College; Since then: Arts administrator, now retired; Then and Now: Marrried to Robert Singleton; Photographed: August 24, 2005; Los Angeles. © Eric Etheridge

I’ve been meaning to write about Eric Etheridge’s project Breach of Peace for too long. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Riders and their key 1961 victory for civil rights.

Today, the anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther Kings 1968 assassination, is an appropriate moment.

Firstly, a brief history of the Freedom Riders, as told by Etheridge:

In the spring and summer of 1961, several hundred Americans — blacks and whites, men and women — entered Southern bus and train stations to challenge the segregated waiting rooms, lunch counters and bathrooms. The Supreme Court had ruled that such segregation was illegal, and the Riders were trying to force the federal government to enforce that decision.

Though there were Freedom Rides across the South, Jackson soon became the campaign’s primary focus. More than 300 Riders were arrested there and quickly convicted of breach of peace — a law many Southern states and cities had put on the books for just such an occasion. The Riders then compounded their protest by refusing bail. “Flll the jails!” was their cry, and they soon did. Mississippi responded by transferring them to Parchman, the state’s infamous Delta prison farm, for the remainder of their time behind bars, usually about six weeks.

A few days after the last group of Riders were arrested in Jackson, on September 13, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued new regulations, mandating an end to segregation in all bus and train stations.

Etheridge’s book Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders features his new portraits of 80 Riders and the mug shots of all 328 Riders arrested in Jackson that year, along with excerpts of interviews with the featured Riders. (See the Breach of Peace archives here)

The Mississippi Museum of Art is showing the mugshots of all 329 Riders arrested in Jackson as a giant, 54′ long mural, along with 20 of Etheridge’s portraits (March 19 – June 12). Free to the public.

Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Freedom Riders installation, Mississippi Museum of Art, March 2011

Etheridge’s work is a continuing multi-year effort. Through interviews and his camera, Etheridge gives his subject the opportunity to return to their political heroics. For those alive in the sixties, Etheridge’s work is an antidote to historical amnesia and for those who weren’t it’s an education.

KING’S GIFT TO HISTORY; A POLITICAL PHILOSOSPHY NOT TO BE FORGOTTEN, ALWAYS TO BE ACTED UPON

And so to King, whose politics are as relevant today as they were 43 years ago. As Jim Johnson reminds us, at the time of his assassination, King was in Memphis in solidarity with sanitation workers, who were striking the city not just for decent pay and working conditions but for recognition of their right to form a union. In light of the concerted, ongoing campaign by Republicans to subvert unions, it surely is plausible to wonder how far we remain from the promised land.

History is very important. Despite their self-label, progressives look back in time as readily as conservatives to pinpoint historical moments to justify their politics. Progressives look to the golden era of people power and the Peace Movement, conservatives hark back to the space-race and Reaganomics.

When history is at our backs, we must choose to leave it behind or let it propel us forward. In the case of the Civil Rights movement, its lessons should be forever in America’s conscience. The work toward social and economic equality is not yet complete, not by a long distance.

We have choices to make and a society to shape.

Which brings me to this potent image of the back of James Earl Ray, who was Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassin.

While hundreds of thousands were marching on the streets and millions across America swelled the turning political tides, James Earl Ray choose a different worldview.

Regardless of colour or creed, Martin Luther King’s promised land was for all … and for a better America. No doubt James Earl Ray was a troubled man but his rejection of America’s sea-change thrust him only in the direction of a dead-end.

James Earl Ray facing the wall at Shelby County Jail. Photo by Gil Michael/Shelby County Sheriff’s Office

As Etheridge explains this is not an act of defiance. Shoved into a Shelby County Jail cell, Ray faces the reality upon him; the physical finality of confinement with nowhere to go. As he abandoned history, so history moved on without him.

TO END ON A GOOD NOTE

REMEMBER.

INSPIRATION, LOVE AND GOOD HEARTS ARE NOT FORGOTTEN BY HISTORY