You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Interview’ category.

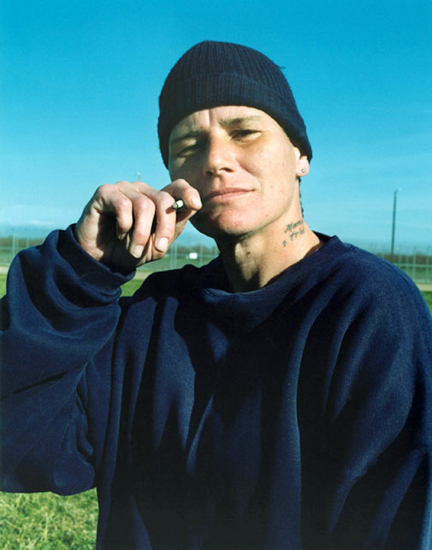

Sye Williams will tell you himself he is not political-engaged in prisons issues. He wanted to shoot a photo-story in a prison and wanted to provide viewers “a slice of life” of the female prisoners at Valley State Prison for Women (VSPW) in Chowchilla, California.

Sye likes to get inside of sub-cultures. In the past, Sye has shot teenage wrestlers, fringe sports-folk and even adopted the persona of a journeyman fighter in order to get inside the world of the amateur boxing circuit. He lost his first bout, but returned a second night with dyed hair and different (leopard skin) shorts to fight again.

Sye, whose film photographs from VSPW have an eerie blue-green institutional patina, visited the prison in 2000. His first impression was that the prison looked like a vocational college. Still, Sye says, “I didn’t see a lot of optimism. […] Everyone always talked about coming back.”

Over five days Sye felt he (and his writing partner and assistants) had virtual unhindered access. Furthermore, he praises the accommodations made by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation for his project. It is unusual for prison photographers to report such freedom within the walls.

Sye is also one of the very few prison photographers to have made multiple portraits of prison staff. He attributes this to the more relaxed atmosphere in a women’s prison. Due to fewer incidents of violence, Sye’s impression was that staff considered work at a women’s prison as a step toward retirement.

Sye’s curiosity leads him to wonder what has happened to the women in the interim ten years and, given the opportunity, he would like to make portraits of them now (whether they are incarcerated or not) a decade on.

We talk about the willingness of women to be photographed, the difficult circumstances of a few of his subjects and the logic of a women’s facility as it compares to a men’s prison.

LISTEN TO OUR CONVERSATION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE

All images © Sye Williams

In 1972, Joshua Freiwald was commissioned by San Francisco architecture firm Kaplan & McLaughlin to photograph the spaces within Clinton Correctional Facility in the town of Dannemora, NY.

In the wake of the Attica uprising in September of 1971, the New York Department of Corrections commissioned Kaplan & McLaughlin to asses the prison’s design as it related to the safety of the prison, staff and inmates. The NYDoC wanted to avoid another rebellion.

The most astounding sight within Dannemora was the terrace of “courts” sandwiched between the exterior wall and the prison yard. It is thought the courts began as garden plots in the late twenties or early thirties, although there is no official mention of their existence until the 1950s.

Simply, the most remarkable example of a prisoner-made environment I have ever come across.

The courts were the focus of Ron Roizen’s 55 page report to the NYDoC on the situation at Clinton Correctional Facility. Sociologist Roizen, also hired by Kaplan & McLaughlin, conducted interviews with inmates over a period of five days:

“Inmates waited months, sometimes even years, to gain this privilege. The groups would gather during yard time to shoot the breeze, cook, eat, smoke, and generally ‘get away from’ the rigors and boredom of prison life.”

In the same five days, Freiwald took hundreds of photographs at Dannemora. Eight of those negatives were scanned earlier this month and are published online here for the first time.

“Since I’d taken these photographs, I’ve come to realize that these are something quite extraordinary in my own medium, and represent for me a moment in time when I did something important. I can’t say for sure why they’re important, or how they’re important, but I know they’re important,” says Freiwald.

Freiwald and I discuss the social self-organisation of the inmates around the courts, his experiences photographing, the air “thick” with tension and surveillance, the spectre of evil, and how structures like the courts simply do not exist in modern prisons.

LISTEN TO OUR DISCUSSION ON THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE

All images © Joshua Freiwald

All images © Joshua Freiwald

Editor’s note: I’ve broken with the PPOTR chronology to bring you Dispatch #12. The decision was made because of the time sensitivity of the issue at hand – California’s Prisoner Hunger Strike. Dispatches 6 to 11 will follow shortly.

“I think the tragedy of this situation is not the prisoners willingness to give up their lives, I think the tragedy is that the CDCR does not see them as human beings,” says Isaac Ontiveros, Communications Director for Critical Resistance and part of the press team for the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity (PHSS) coalition.

The PHSS is made up of grassroots organizations & community members committed to amplifying the voices of hunger strikers.

The strike originally ran from July 1st – July 22nd. It was suspended briefly to investigate the viability of concessions made by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. These were unsatisfactory and the strike resumed September 26th.

LISTEN TO OUR CONVERSATION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY ON THE ROAD PODBEAN PAGE

Ontiveros and I spoke on October 11th, day 15 of the resumed hunger strike.

TIMELINE OF THE CALIFORNIA PRISONERS’ HUNGER STRIKE

For three weeks in the month of July, 6,600 California prisoners* took on a hunger strike against the conditions of solitary confinement at Pelican Bay & other prisons. The strikers made five demands: access to programs, nutritious food, an end to collective punishment, compliance with the US Commission on Safety and Abuse (2006), and an end to the “debriefing” practice that affiliates prisoners to gangs; a process vulnerable to manipulation and false evidence.

Late in July, the strike was suspended but due to the slow and “inadequate” response of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s response it was clear there was a need for the protest to resume. On September 26th the strikers refused meals once more.

On October 15th, after nearly three weeks, the prisoners at Pelican Bay ended the resumed strike.

The prisoners cited a memo from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) detailing a comprehensive review of every Security Housing Unit (SHU) prisoner in California whose SHU sentence is related to gang validation. The review will evaluate the prisoners’ gang validation under new criteria and could start as early as the beginning of next year. “This is something the prisoners have been asking for and it is the first significant step we’ve seen from the CDCR to address the hunger strikers’ demands,” says Carol Strickman, a lawyer with Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, “But as you know, the proof is in the pudding. We’ll see if the CDCR keeps its word regarding this new process.” (Source)

Ontiveros and I discuss the history of hunger strikes, the unprecedented scope of the strike in the U.S., the necessity of the demands, late summer negotiations and retaliations by the CDCR and the need for continued awareness of this still developing struggle.

In the context of the sit-in within the Georgia prison system in December of last year, the California hunger strike indicates a growing political awareness of U.S. prisoners to their conditions and invisibility. “Our bodies are all we have left,” says Ontiveros assuming the position of an incarcerated striker.

Generally, prison strikes can be played down by authorities and overlooked by national mainstream media. As our discussion proves, awareness of the details in cases such as this are critical. We cannot wait for deaths to be knowledgable of the issue. Please watch developments in California to see if meaningful results for the CDCR and prisoners can be agreed upon and shared.

*6,600 is an official estimate, and the lowest possible figure. Some reports put the figure at nearly double that at 12,000.

PRISONER HUNGER STRIKE SOLIDARITY

Coalition partners include: Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, All of Us or None, Campaign to End the Death Penalty, California Prison Focus, Prison Activist Resource Center, Critical Resistance, Kersplebedeb, California Coalition for Women Prisoners, American Friends Service Committee, BarNone Arcata and a number of individuals throughout the United States and Canada. For more info on these organizations, visit PHSS’ resources page.

CRITICAL RESISTANCE

Critical Resistance seeks to build an international movement to end the Prison Industrial Complex by challenging the belief that caging and controlling people makes us safe. We believe that basic necessities such as food, shelter, and freedom are what really make our communities secure. As such, our work is part of global struggles against inequality and powerlessness. The success of the movement requires that it reflect communities most affected by the PIC. Because we seek to abolish the PIC, we cannot support any work that extends its life or scope.

Leonard Freed’s Police Work, Don McCullin’s Vietnam Inc., Cornell Capa’s The Concerned Photographer, books by August Sander, Robert Frank, Eugene Smith, Gilles Peress, Susan Meiselas and Jim Goldberg. So reads Robert Gumpert’s bookshelf.

Bob admires these photographers for their craft, storytelling and humanity. For want of a better word, they are his heroes; in some cases, they are his friends.

Of all photographers, Bob singles out McCullin as the shining example, “His work didn’t always look very optimistic, but he was an optimistic person.”

“I’m not sure McCullin was overtly political. He was just overtly and achingly human,” say Bob. “He took pictures you cannot turn away from … the humanity of them; they’re unflinching.”

Why do I bring this up? Well, during our interview Bob and I discussed at length the photography we admire and Bob talked about that which we should seek to see, digest and – dare I say it – emulate. Those discussions fell to the cutting room floor during editing, but they are worth mentioning here to offer context to the type of photographer Bob is.

I’ve known Bob a long time but until our latest chats I never realised how sacred he holds the role of the photographer to speak truth to power.

Bob began shooting U.S. labour movements. In 1974, he was in Harlan County for the miner’s strike. A long time before he photographed inmates of the San Francisco County Jails, he was photographing the homicide detectives and beat cops of the San Francisco Police Department. It’s about duty, work conditions, getting up in the morning, taking a pay packet home. “There’s nothing more heroic than working a shitty job, one that might ultimately kill you, to take care of your kids and send them off in a better position than you were,” says Bob.

Photography should never be a prop or illustration, photography should never get in the way of communicating humanity, photography should (despite it’s biases) always avoid objectifying its subject. Photography is about people.

Bob uses the example of Jacob Riis, a man known for his pioneering use of photographs to show America the squalid conditions of immigrant tenements. “Riis was a crusader, not in the George Bush sense, but in the sense he saw a need. He never considered himself a photographer.”

Riis used photography as a tool to address a need. After his campaigning he didn’t use photography in the same way. The issue was primary, “I liked that,” says Bob, “It was a direct action use of photography.”

‘TAKE A PICTURE, TELL A STORY’, IN THE SAN FRANCISCO COUNTY JAILS

The premise is simple. He takes a portrait, they tell him a story. It’s a trade.

View images and listen to audio from the project at Take A Picture, Tell A Story.

Robert Gumpert has made portraits and audio interviews of inmates in the San Francisco County Jail system for six years. He doesn’t describe himself as a journalist or an activist, he is just a human being with a curiosity in stories and a promise to be honest. The tales his subjects tell are as eye-opening as Bob is modest. The project is ongoing and the archive is one of otherwise forgotten stories.

LISTEN TO ROBERT GUMPERT AND I TALK ABOUT HIS EXPERIENCE PHOTOGRAPHING THE THE SAN FRANCISCO COUNTY JAIL SYSTEM

BIOGRAPHY

Robert Gumpert is a San Francisco-based freelance documentary photographer. He started his career in Harlan County, Kentucky, in 1974, documenting what turned out to be the last three months of the epic United Mineworker’s strike photos from which are part of the Coal Employment Project Records Appalachian Archives in East Tennessee State University.

In 1998 and 1999, Gumpert’s photographs of garment workers Faces Behind the Labels were shown as part of a traveling exhibit of garment workers mounted by Oakland’s Sweatshop Watch

Since the mid nineties, Gumpert has documented many sides of the criminal justice polygon – homicide detectives, courts and public defenders, SFPD, and the inmates and deputies of the SF County Jail system. The series is called Lost Promise: The Criminal Justice System.

Gumpert’s work from the San Francisco County Jails can be seen and heard at a dedicated website Take A Picture, Tell A Story.

Before turning his attentions to these regional issues, Gumpert traveled the world as a photojournalist. Gumpert’s photos have been used in outreach media by the University of California’s Center for Occupational and Environmental Health. He was formerly a photographer under contract with the California Department of Industrial Relations. He has exhibited his work at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. In 2011, his portraits from the San Francisco county jails were exhibited at Foto8 Gallery show Locked and Found in London.

His website is http://robertgumpert.com/

In his kitchen, Bob listens to the audio of an earlier PPOTR interview

“Prisons don’t work. They didn’t work in the eighteen-hundreds, they never worked in the nineteen-hundreds and they certainly don’t work in the 21st century,” says Dan Macallair, founder and executive director of the Center on Juvenile Criminal Justice (CJCJ).

Since the late 80s, Dan has called for community supervision instead of incarceration and, in cases where incarceration is necessary, for it to be carried out at the local level. Prisons are large (and often violent) and inmates can be sent to any part of the state. Local county jails have – in San Francisco at least – proved to be more flexible institutions and more successful in providing relevant programs preparing inmates for release back into their community.

Dan and I spoke about San Francisco’s leading role as a county in California willing to take risks and trial new strategies for rehabilitating prisoners. We also note how model programs developed by the CJCJ have been adapted nationwide.

On October 1st, California began its “Realignment” program; prisoners transferred from state prisons into the county jails and local jurisdictions. The move is the result of a Supreme Court ruling in May that ordered California to reduce it’s prison population by approximately 32,000 because the state prisons were overcrowded and unable to provide adequate health care.

In this context, we discuss what this means for California’s criminal justice system and the opportunities for organisations such as CJCJ to introduce progressive solutions that benefit the community, the criminal, the families, the victims and the taxpayers.

Dan notes that never in his experience has he seen a Secretary of the California Department of Corrections advise other jail and prison systems NOT to do what California has done. Matt Cate, the current Secreatary is doing that.

California’s prison boom and prison failures are a national example … for all the wrong reasons.

“I weep when I think it took this Supreme Court, with its conservative bent, to tell liberal California that its prison system is broke.”

LISTEN TO THE INTERVIEW WITH DAN MACALLAIR AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE

BIOGRAPHY

Daniel Macallair is the Executive Director and a co-founder of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. His expertise is in the development and analysis of youth and adult correctional policy. He has implemented model community corrections programs and incarceration alternatives throughout the country. In 1993, Mr. Macallair established the Detention Diversion Advocacy Program (DDAP) for serious and chronic youth offenders in San Francisco’s juvenile justice system. This program was cited as an exemplary model by the United States Department of Justice and Harvard University’s Innovations in American Government program. In 1994, Mr. Macallair received a leadership award from the State of Hawaii for his efforts in reforming that state’s juvenile correctional system and developing model community-based reentry programs. In August 2007, Mr. Macallair initiated a technical assistance project to assist California counties in developing model intervention programs for high-end youthful offenders. Mr. Macallair is presently involved in the efforts to reform California’s adult sentencing and parole practices and serves as an advisor to the State’s prestigious Little Hoover Commission.

In 1996, David Inocencio began writing-workshops to youth detained in S.F.’s Youth Guidance Center. A zine developed and The Beat Within was born. It is the nation’s biggest weekly publication of incarcerated youth writing.

The first publication followed the murder of rapper Tupac Shakur as young people sought ways to publicize their feelings of loss. Originally, The Beat Within was a 6-page magazine. Today the full-fledged weekly magazine is at 70 pages.

For some contributors, The Beat Within is the first positive recognition they have ever received that they have a voice worthy of an audience.

The Beat Within staff and volunteers hold weekly workshops in many California county juvenile halls: San Francisco, Marin, Alameda, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Solano, Monterey, and Fresno. The Beat workshop model is replicated in Maricopa Arizona, in San Bernalillo New Mexico, Miami Florida, and Washington DC.

Each week, The Beat Within serves up to 700 detained youth and the San Francisco office provides internships and social services to more than a dozen formerly detained youth.

David Inocencio and I spoke about what it means to give juvenile prisoners a voice.

LISTEN TO OUR DISCUSSION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE.

Below is To The Streets, a piece of writing by Lady Streetz, from Alameda, CA. It featured in Volume 16. 18/19 (p. 6) of The Beat Within.

It is a difficult read but it gives us an unmistakable view of some of the serious problems incarcerated youth, and particularly incarcerated women face.

Dear Streets

I want to write this letter to tell you how ashamed of you I am. How could you ever raised your hand to a female, what I want to know is what did I do so wrong that you had to lay your hand on me for the last months and months?

Why would you beat me, kick me out of my own car, and make me walk home bare foot? Where the hell do they do that at? I can’t believe you had the nerve to beat me in front of your friends and then make me sit out in the cold in my little dress.

Who gave you the nerve to take my keys and my phone? Did you buy my car, no! Did you buy my phone, hell no! Someday I hope to forgive you for all the shhh you did to me. Someday I will forgive but I will never forget.

I will never be the same since you happened to me. I stride to try to trust the black men staff here, but I’m scared they’re going to hurt me. I’m always scared someone is about to abuse me. Why? Because of you, because of all the times you beat me and left me bleeding. I hate you, You’ll never change women beaters.

Artist unknown © The Beat Within

David, DJ at the prison radio station holds a Polaroid of him and his wife. He said the picture was taken more than 15 years before, when he was 18 and she was 16 years old. During his hour as DJ he played mostly Gospel and Christian music at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, June 27, 2000.

Photographer, writer and psychotherapist Adam Shemper and I talk about his portraits and photographs from Louisiana State Penitentiary.

LISTEN TO OUR DISCUSSION AT THE PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY PODBEAN PAGE.

At the age of 24, Adam was challenged (almost dared) by a family friend to “experience something real.” The friend offered him an introduction to warden Burl Cain and the test to photograph within Angola Prison.

We all have difficulty putting our work out in the world, and Adam found that after his nine-month stint at Angola he had more questions than answers.

For many years the work remained unpublished and Adam’s own justifications for the work unsteady. We discuss the life-cycle of the photographs, the reactions of the prisoners to Shemper and his work, and generally, the responsibilities of photographers toward their subjects.

In photography, as in life, it is all about relationships and positive connections that benefit all parties.

Victor Jackson, cell block A, upper right, cell #4. He had ‘I Love U Mom,’ tattooed on the inside of his right forearm. Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000.

LaTroy Clark, cell block A, upper left, cell #6, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Don Jordan reads the Bible in his cell, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Jonathan Ennis puts a puzzle together of a farm scene in Ward 2 of the Louisiana State Penitentiary hospice at Angola, March 21, 2000.

A man sleeping during the day in the main prison complex, camp F dormitory, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, February 1, 2000.

Henry Kimball and Terry Mays in cell block A, upper right section, cell #15, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, September 6, 2000.

Brian Citrey, main prison, cell block A, upper right, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000

Nolan, a prison trustee, standing in front of the lake, where he often spends his days fishing. He caught catfish and shad on this day for the warden and his guests. Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, June 27, 2000.

Man cuts open sacks of vegetables to sort through, Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, June 27, 2000

After chopping weeds in the fields, men wash up as they transition back to their cell blocks at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, April 17, 2000.

Men housed at prison camp C dig a ditch at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, January 31, 2000.

All images © Adam Shemper.

Images may not be reproduced elsewhere on the web or in print without sole permission of the photographer, Adam Shemper.