You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Opinion’ category.

I have not and will not ever go through 90,000 pages of wikileaked documents covering US military operations (January 2004-December2009). But, if the Guardian tells me its legitimate and important, I’ll begin with that understanding.

What then, when Mother Jones – more precisely Adam Weinstein – comes along and tells me not to believe Assange’s hype?

Adam Weinstein at Mother Jones dismisses the import of the Afghan War Logs on wikileaks:

“In truth, there’s not much there. I know, because I’ve seen many of these reports before – at least, thousands of similar ones from Iraq, when I was a contractor there last year. I haven’t been through everything yet, but most of what you see on WikiLeaks are military SIGACTS (significant activity reports). These are theoretically accessible by anyone in Iraq, Afghanistan, or the Tampa, Florida-based US Central Command—soldiers and contractors—who have access to the military’s most basic intranet for sensitive data, the Secret Internet Protocol Router Network (SIPRNet). Literally thousands of people in hundreds of locations could read them, and any one of them could be the source for WikiLeaks’ data.”

My question: Just because it is easy for service personnel or contractors to view the material doesn’t change the significance this leak has for the general public in its capacity to form a view of the war based on new material, does it? Weinstein counters again, “By and large, like most of the stunts pulled by Assange, this one’s long on light and short on heat, nothing we didn’t already know if you were paying attention to our wars.”

Weinstein does make the valid point that the lives of Afghan collaborators are now at risk, as their names are not redacted from the material.

Ultimately though, I fear the coverage of the leak may develop into a character dissection of Assange and “discussion” of the relative merits of new-journalism; the former will dominate and the latter could be fruitful but will probably miss the point.

I am in support of wikileaks, but mainly because I am opposed to the war. I don’t feel our media does a good enough job at getting to the realities of war for the American news consumer. We saw just last week that the mainstream media ceased using the word torture for water-boarding almost overnight. That linguistic culture shift suggests to me that the mainstream media are as subject to political pressures as any individual … so, why shouldn’t we have wikileaks mix it up? And why shouldn’t we think about the flows of information: or the definition of free media: or tactics are served when information is kept classified, hidden?

Was it an inside act of rebellion?

I have absolutely no grounds on which to make an accusation, which is why I phrase it as a question.

But just looking at the foolish doctoring of images, especially the helicopter cockpit image, I wonder if the culprit intended to be caught? The color of the photoshopped image is just ludicrous, literally unbelievable, unless that is Martin Parr’s Gulf of Mexico!

To me, the reworking seems suspiciously blatant. Who is the “contract photographer” doing these pig-eared photoshoppings? And, is he/she a saboteur?

Original. © BP p.l.c.

Botched photoshop. © BP p.l.c.

INTERNET MEME

Rather joyously, this image has become a meme. See the comments in the original and excellent Gawker article!

Image courtesy Edgar Martins/HotShoe Gallery

I’d agree with Joerg that We Need Better Critical Writing About Photography. This is pretty simple task – just cut out the jargon. Having posted On Statements last month, Joerg is only demanding the same of critics as he is of photographers.

Which brings me to Exhibit A: Photographer, Edgar Martins is talking bollocks again.

“One could argue that this work seeks to communicate ideas about how difficult it is to communicate. My images depend on photography’s inherit tendency to make each space believable, but there is a disturbing suggestion that all is not what it seems. The moment of recognition that there is something else going on, the all too crucial moment of suspended disbelief, is the highest point that one can achieve. This process of slow revelation and sense of temporal manipulation is crucial to the work. Above and beyond this, in having to shift between the various codes, the viewer becomes acutely aware of the process of looking, of the reconciliation required between sensory and cognitive understanding. As you rightly say, it is difficult to know for sure if what you are looking at is a photograph. However, they are photographs.”

Déjà vu

You might remember Edgar Martins. He’s the photographer who photoshopped images of foreclosed America for the New York Times. It was one of the more substantive photoshop kerfuffles of recent years.

I remember at the time thinking that the way Martins wiggled his way out of the controversy was skilled; he put all his energies into How can I see what I see, until I know what I know? a meditation on truth in photography, diluting his deception in M.F.A. critical theory references.

Martins confused 90% of his detractors with his busy response and sapped the energy of the remaining 10% who were looking for the next headline anyway.

He really intrigues me!

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Thanks to Alan Rapp for the tip-off.

Talk to anyone about American documentary photography, they’ll probably mention Danny Lyon. Talk to anyone about prison documentary photography and they’ll definitely mention Danny Lyon.

In terms of US prison journalism, Lyon was the first photographer to a) give a shit, b) gain significant access, and c) distribute journalist images far and wide.

I had read Nicole Pasulka’s interview with Danny Lyon when it was published for The Morning News in December, 2008. I have since begun reading Like a Thief’s Dream (currently 100 pages deep). As in many cases, it takes an AmericanSuburbX reissue to press the issue.

Renton in his cell, Walls Unit, Huntsville, Texas, 1968. © Danny Lyon

I have a few things to say about the chapters I’ve read so far, but those thoughts need more brewing. While I mash those brain-hops, I’d like to draw your attentions to Lyon’s comments about prisons in America:

“You really need a friend, or family member inside a prison, to appreciate what we are doing. America has two million people inside of her prisons. Only China, a dictatorship, tops us in this growth industry. I like to think of the words of Fredrick Douglas “Be neither a slave nor a master.” All of us, outside of prisons, are the masters.“

“Prisons should be turned into bowling alleys, schools, and daycare centers, or demolished. We could probably do better with 90 percent of the inmates being released. Communities should deal with offenders on a local level. Review panels should meet with all of the 200,000 prisoners doing life sentences. Many of these people are harmless and aged, and should be released. I would like to see review panels sent into all the prisons, to meet with inmates face to face. Most should be released.“

“When I was working in the Texas prisons (1960s and 70s) there were 12,500 men and women inside and no executions. Today there are 200,000 in Texas and they kill prisoners all the time. Prisons are now everywhere, a major employer in upstate New York. Simply put, everything about prison is worse.”

“The best way to change yourself is to go outside your world into the world of others. It’s a big world out there. The worst thing about New York City is that all the young people that gather there are extremely like-minded. Creative people are comfortable there, but they are preaching to the choir. I always wanted to move Brooklyn to Missouri. Everyone would benefit.” (Source)

I couldn’t – and have not – ever put it better myself.

– – – – – – – –

Buy a signed copy of the book Like a Thief’s Dream at Danny Lyon’s website, Black Beauty.

Postcard sent by the author to Renton in prison in the early 1980s

Afghanistan is a very poor country, placed 174th out of 178 in the Human Development Index. The literacy level is 50% for men and 20% for women and the average life expectancy is below 44 years. Only one in three people have clean drinking water and life expectancy is 43. It has suffered many years of war. This is a very challenging environment in which to introduce a formal, state-wide justice system based on written texts, record-keeping, databases (and a regular supply of electricity) and all the appropriate protections for the rights of suspects, defendants and prisoners that accompany such systems in the West.

Source: Alternatives to Imprisonment in Afghanistan. A Report by the International Centre for Prison Studies (February 2009)

Manca Juvan, the subject of a post on Sunday, also photographed in an Afghanistan women’s prison. Juvan is only one of several photographers to take on this subject matter – Anne Holmes, Andrea Camuto, Katherine Kiviat, and David Guttenfelder being others.

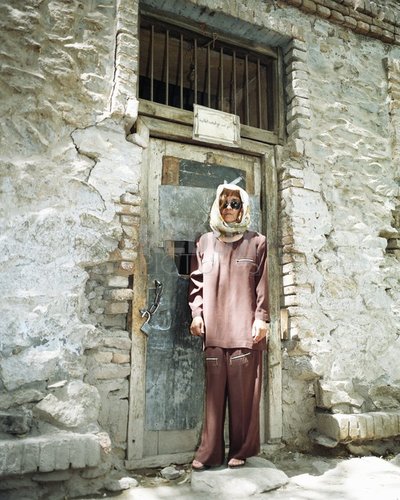

The entrance door to Walayat Women's Prison, Kabul. Currently 33 women and 16 children are kept imprisoned. © Manca Juvan, May, 2003

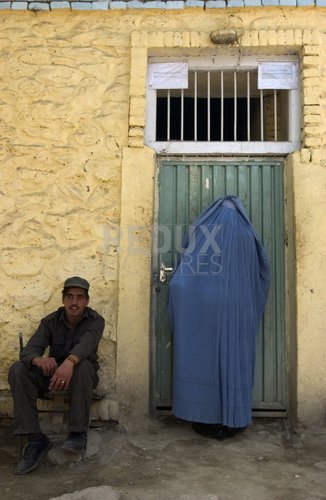

Suhila Fanoos, 25 years old, Walayat women's Prison guard standing in front of the Women's prison holding 32 female inmates for crimes such as skipping home and leaving their family responsibilities. Sign above her head reads "Prison of Women". Photographed in Kabul, Afghanistan July, 2003. © Katherine Kiviat/Redux Pictures

HOW TO APPROACH THESE PHOTOGRAPHS?

The portfolios of Juvan and her contemporaries had me thinking. Many photographs were from 2003 or later in 2007/08 (due to media coverage of allegations of abuse or the construction of a new prison).

I’d like to present a few images, but am I only comfortable doing so if I also provide an accurate summary as it is NOW for women imprisoned in Afghanistan.

Firstly, I just like to point out the two pairings above and below. Kiviat and Juvan (above) both show the same portal at Walayat women’s prison, Kabul. In 2004, one year later, Kiviat also photographed this door which is the same as that shot by Andrea Camuto (below). Camuto identifies the door as belonging also to Walayat women’s prison.

The women's prison in Kabul, A woman speaks to female prisoners through the peep hole of the prison door. © Katherine Kiviat/Redux. 2004

Visitation, Walayat woman's prison, Afghanistan © Andrea Camuto

WAYALAT WOMEN’S PRISON

Wayalat still operates as a prison, but it no longer houses female inmates. A 2003 IRIN report detailed the dire need for humane facilities at Wayalat:

‘According to Lt-Col Habibuallah, in charge of Wolayat prison, the present building with its 17 rooms and four toilets was built some 90 years ago to accommodate up to 200 people. “There are 511 men and 32 women imprisoned here,” he said. There were no categories for offenders and the accused and convicted were generally mixed together, including some inmates on death row. “There are no basic facilities, no ambulance, no proper medicine and health care, and the increasing problem of overcrowded rooms is a tragedy,” Habibuallah said. Even the 35 staff members lacked access to a toilet and were forced to sleep on the roof or in the courtyard at night. “We have worse conditions than the prisoners,” he claimed. Women inmates fare slightly better. Located in a separate building, the painted cells house between five and seven prisoners each, but the lack of adequate health care is felt more by the detained women.’

Manca Juvan‘s work focused on the women and their children in Wayalat. Katherine Kiviat‘s work is part of a larger body of work describing the new roles and careers (including that of prison guard) of women in Afghanistan. The collection is called Women of Courage.

Andrea Camuto‘s work, shot in 2005, 2007 & 2009 followed returning refugees and the “forgotten” women of Afghanistan to the cheaper countryside rents, to the hospitals … and to the prisons if necessary.

The common theme for these photographers is the injustice suffered for many women whose imprisonment is based upon judgement for “moral crimes” and “bad character” including sentences for adultery (which includes inappropriate acts both in and out of wedlock), being drunk, wanting a divorce or even just leaving a husband for a night to stay with family after suffering a beating.

PUL-E CHARKI

On the outskirts of Kabul, Pul-e Charkhi is Afghanistan’s most notorious prison. It has been used by every regime to house it’s enemies.The unearthing of mass graves in 2002 confirmed the Soviets’ use of the site for mass-killings and the Americans adopted and expanded the prison to house Taliban fighters. In 2006, there was a major rebellion and riot by the prisoners.

Anne Holme‘s work from Pul-e Charkhi was conducted in 2007. Holmes’ story is that of the struggle to raise children inside the walls, the quashing of legal rights and despite the “warden’s genuine concern” the inability of the justice system to provide fair hearing for the women.

Pul Charki's womens prison just on the outskirts of kabul is rough living. Inmates do not receive adequate medical attention, they cannot send or receive mail, and many of the women there have yet to learn the crime with which they have been charged. © Anne Holmes

In April 2008, David Guttenfelder visited Pul-e Charkhi. His work, Kids in Prison reveals disturbing figures – “There are 226 young children in Afghanistan’s prisons, including many who were born there. They have committed no crime, but they live among the country’s 304 incarcerated women.”

Jamila, left, plays on a seesaw with children of other female inmates on the prison yard of Pul-e Charkhi prison in Kabul, Afghanistan April 17, 2008. Jamila, age 7, and her mother, Najiba, who is serving a seven year sentence for adultery, have been in prison for 10 months. © David Guttenfelder/AP

Pul-e Charkhi was a brutal living environment. This report details inadequate sanitation, frigid winter temperatures, rape and humiliation.

In the same month that Guttenfelder photographed – April, 2008 – the women and children of Pul-e Charkhi were moved to a new purpose built facility. Recognising the special requirements of female prisoners, Badam Bagh was constructed by the United Nations Drugs and Crime Office (UNODC) with the financial support of the Italian Government.

The two videos below offer some comparison between the two facilities:

PUL-E CHARKHI

BADAM BAGH WOMEN’S PRISON

LYSE DOUCET AT BADAM BAGH

To bring us right up to date, the best reporting is not that in the photographic medium, but straight news reporting. Lyse Doucet‘s report for the BBC is a must see.

(I have applauded Doucet’s journalism in the mens’ wings at Pul-e Charkhi before).

At a moment when the White House is to open talks with the Taliban and the media is comfortably using the phrase “unwinnable war”, it is perhaps responsible to consider the lives of those caught up in the broken justice system of Afghanistan. The prisons of Afghanistan are one of the last priorities for a society that is war torn and divided. Afghanistan hasn’t got the resources to support the basic human rights of those it incarcerates when the rights of those outside prison walls cannot be guaranteed.

If you are in NYC and you’re quick on your feet you might just make it to Zwelethu Mthethwa’s artist’s talk tonight. Followed by a reception and book signing at Museum of Contemporary Diasporan Arts in Brooklyn (begins at 6.30pm).

Mthethewa’s work will be on view at The Studio Museum in Harlem until October.

AFRO-PESSIMISM

Afro-Pessimism is a term introduced by Okwui Enwezor (for the essay of Mthethwa’s monograph) in an attempt to describe what Zwelethu Mthethwa’s art is not.

I had dozens of working titles for this blog post each one reflecting an approach (and/or quote) by Mthethwa which described his process, his collaboration with the sitter, the waves of culture in which we exist, whether poverty in photography is a problem for the practitioner or audience, etc, etc. These topics are too huge for a title of course, fortunately there’s plenty of wonderful online videos and chances to hear Mthethwa talk about his art:

Aperture (who are publishing his first monograph) has a four-part interview, Zwelethu Mthethwa: In Conversation with Okwui Enwezor.

The Mail & Guardian has a narrated slideshow, “I hope when people look at these images they are honest and open to learning new things.”

Dazed and Confused visited Mthethwa in his studio, which is a fascinating look at his work space. A great painter as well as a great photographer!

ESSAY

For the SFMoMA ‘Is Photography Over Symposium’, Okwui Enwezor leans on Mthethwa’s work to ask, “How do diverse cultural practices engage with the legacy of photography?”:

“Before foreclosing the effectiveness of photography or to ask whether we have reached the end of photography, we should address the diverse manifestations of photography in societies in transition where its powerful effects of seeing is constantly battling different logics and apparatuses of opacity. All through the years of apartheid, photography was at the center of this battle between transparency and opacity, thus lending the medium a far more discursive possibility than it would have enjoyed as purely an instrument of art. One can in fact, argue, pace Georges Didi-Huberman, that in the context of apartheid photography was an instrument of cogito.”

“In South Africa, for the critics of documentary realism or anthropological realism, especially black artists such as Mthethwa, documentary realism was always at the ready to link the iconic and the impoverished with little recourse to examining its spectral effects on social lives. Because of this, documentary realism generated an iconographic landscape that trafficked in simplifications, in which moral truths were posited without the benefit of proven ethical engagement.”

From what I can gather Georges Didi-Huberman’s thesis is that images are killed, denied their truth, narrative or violence within the dominant art historical canon that has elevated the image to art. The image becomes cogito – an object of thought – not an object pertaining to reality or even to action.

Mthethwa’s images are against such failings; they are attempts at transparency, honesty. Mthethwa talks in the interviews about his ethical and slow engagement with his subjects.

Afro-Pessimism is on the decline.

BIOGRAPHY

Zwelethu Mthethwa (born in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, 1960) received his BFA from the Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town, a then–whites-only university he entered under special ministerial consent. He received his master’s degree while on a Fulbright Scholarship to the Rochester Institute of Technology. Mthethwa has had over thirty-five international solo exhibitions and has been featured in numerous group shows, including the 2005 Venice Biennale and Snap Judgments at the International Center of Photography, New York. Mthethwa is represented by Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. He lives in Cape Town, South Africa.

Scott Fortino‘s book Institutional: Photographs of Jails, Schools, and other Chicago Buildings (2005) is important because it hit the shelves two years prior to Richard Ross’ Architecture of Authority (2007).*

People tend to think of Richard Ross’ Architecture of Authority as being the authoritative (pun unintended) photographic statement on use of identical spatial psychologies across the breadth of contemporary institutions. Perhaps Fortino can, and should, disrupt that position.

Patently, the publishing date of a book doesn’t close the argument, but I think it is apt to call these two photographers contemporaries in every sense of the word.

There are differences between Fortino and Ross’ work. Fortino’s work looks exclusively at Chicago institutions, whereas Ross – powered by a Guggenheim grant – took his survey international.

Fortino has an unusual bio, working as a photographer and police patrolman. Ross, on the other hand, is a professor in photography for the University of California, Santa Barbara. Interestingly, Ross, the son of a policeman is open about his father’s influence on his work.

I’d really like to see Fortino sat down giving a commentary on his work, just as Ross has here. Better still, I’d love to see Fortino and Ross at the same table!

– – – –

Scott Fortino’s Institutional portfolio, and more here from the Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago.

BIO

Scott Fortino is a photographer who also works as a patrolman with the Chicago Police Department. His photographs are in the permanent collections of the LaSalle Bank of Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and numerous private collections.