You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Portraiture’ category.

Photographer Tony Fouhse photographed his hometown of Ottawa. Then he made a newspaper of his images and gave all 2,000 of them away for free. The project is called Official Ottawa.

I dig Fouhse’s images of politics, power, pomp and circumstance in Canada’s capital. The concept was great, the execution fine and the distribution in cafes and at truck-stops brings a smile to my face.

FREE FOTOGRAFY WILL SET YOU FREE!

I interviewed Tony about the project for Vantage in a piece titled Control and Containment in the Canadian Capital.

About Ottawa, Fouhse says:

“There is a kind of pervasive fear that percolates through the city. Not a fear of getting mugged or anything, rather, a fear of saying or doing the wrong thing. Workers here seem to know which side of their bread is buttered and who is buttering it; they certainly wouldn’t want to put their pensions at risk. An atmosphere like that dampers a lot of healthy thinking and questioning and certainly precludes action.”

–

There’s a couple of interviews with a couple of photographers I greatly admire currently up on Vice.

WASHINGTON STATE

Photographing America’s Pregnant Prisoners is a conversation with Cheryl Hanna-Truscott, nurse, midwife and photographer who for 12 years has made double-portraits of incarcerated women and their babies at the Washington Corrections Center for Women (WCCW).

In the past, I have flagged Hanna-Truscott’s work, curated it into a pop-up show about Washington State prisons, and featured it in online exhibitions. Hanna-Truscott has recently released Purdy a documentary film about the WCCW mothers and babies unit. Hanna-Truscott volunteers at WCCW.

A note on the film’s title: Purdy is the local town in which WCCW sits. Purdy is also how the prison is known to locals. Additionally, “purdy” is a hokey variation of the word pretty. I think it’s a clever title for this project which simultaneously challenges stereotypes, pays homage to maternal cycles, finds care and within a punishing institution but neither ties the issue off with easy answers.

Hanna Truscott’s photographs are moments of solace amid what she describes as beyond difficult circumstances for the mothers.

“A lot of the women are traumatized. Sometimes they have learning disabilities or they’ve never had anyone who could vouch for them – so they have low education levels and no skills. Which means they also have employment issues when they get out. When they’re released, get $40, a change of clothes and a bus ticket. So they have to start a new life — and for the women I work with, that’s also with a baby.”

Visit Hanna-Truscott’s devoted site Protective Custody.

NEW YORK STATE

Photographing Trips to Visit Family Members in Prison is an interview with Jacobia Dahm. I’ve spoken with Dahm previously (cross posted to Vantage) and her work has proved very popular since its release earlier this year.

Families have suffered most from the politicised decisions on where to construct prisons. Granted many Upstate New York prisons predate mass incarceration (1980-) but many many more have been constructed in recent decades. Across the nation prisons have been built in remote locations.

Dahm says:

“Your crime has no bearing on the fact that you are still one of the most important people if not the most important person in a child’s life. In ways, it is costly not to support these family bonds, for the generation in prison and for their offspring. Children should have easy access to their parents, and vice versa, and it is something that other prison systems around the world manage to take into account and work with.”

If prisons had been used as jobs programs for depressed post-industrial American towns then we might have seen them built closer to the communities from which the prisoners have been extracted.

A NOTE ON VICE

Remember when VICE used to be nothing but public humiliation, photos of homeless, Dos & Don’ts and pre-hipster snark? Well, it is changing. By my reckoning. It’s going to take a lot to get out from under those punk-ass early years but they’re equipped to do it. VICE Media is worth $2.5 billion and I think I read somewhere that VICE has 1,500 staff and freelancers operating out of its New York HQ alone.

So, now what we have at VICE is genuine concern beyond the snark. This is something that Stacy Kranitz reflects on in a She Does Podcast published this week. It’s a great conversation all-round reflecting upon the many sides of things.

As for VICE and prison coverage, it looks like we’ll get more investigative reporting and less stereotypes and cheap gags. An overdue sea change. The VICE series America’s Incarcerated runs throughout October.

Susan Stellin and Graham MacIndoe are raising money to fund the exhibition of their project American Exile at Photoville this autumn.

DONATE TO AMERICAN EXILE HERE

American Exile is a series of photographs and interviews documenting the stories of immigrants who have been ordered deported from the United States, as well as their family members – often, American citizens – who suffer the consequences of the harsh punishment and are sometimes forever separated from a parent or partner transported to foreign lands.

These are people who, ostensibly, have — just as you or I — lived, worked and paid taxes in the U.S. for extended periods. Bar fights that occurred 20 years ago, Visa paperwork deadlines missed, and other minor matters have sometimes led to deportation.

The tumorous growth America’s prison industrial complex goes back four decades whereas the focus of Graham and Susan’s work — the establishment of an extended archipelago of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facilities — is a much more recent, post 9/11 phenomenon. It is utterly contemporary and it meets the desperate need for journalism that probes ICE procedures.

DONATE TO AMERICAN EXILE HERE

MacIndoe spent five months in immigration detention in 2010, facing deportation because of a misdemeanor conviction – despite living in the U.S. as a legal permanent resident since 1999. After winning his case, he and Susan began gathering stories of families caught up in deportation proceedings, including asylum seekers, green card holders, and immigrants trapped in the bureaucracy of adjusting a visa.

I love Graham and Susan. They have a very comfortable couch. We’ve been friends for several years. Susan has a keen sense of justice and nous for a story and the will to bend an industry to our needs, not its. Graham is an addict who got clean, a street shooter, an artist, a great teacher (by all accounts) and a bit of a curmudgeon for all the right reasons.

–

DONATE TO AMERICAN EXILE HERE

–

BIOGRAPHIES

Graham MacIndoe is a photographer and an adjunct professor of photography at Parsons The New School in New York City. Born in Scotland, he received a master’s degree in photography from the Royal College of Art in London and has shot editorial and advertising campaigns worldwide. He is represented by Little Big Man Gallery in Los Angeles, and his work is in many public and private collections. Follow Graham on Instagram and Twitter.

Susan Stellin has been a freelance reporter since 2000, contributing articles to The New York Times, New York, The Guardian, TheAtlantic.com and many other newspapers and magazines. She has worked as an editor at The New York Times and is a graduate of Stanford University.

In 2014, Susan and Graham were awarded a fellowship from the Alicia Patterson Foundation for their project, American Exile, and are collaborating on a joint memoir that will be published by Random House (Ballantine) in 2016.

–

DONATE TO AMERICAN EXILE HERE

I was interviewed by ACLU recently: Prisons Are Man-Made … They Can Be Unmade.

The Q&A focuses around the exhibition Prison Obscura and you’ll notice a return to many of my favourite talking points. Still, the work never ends, and I know that ACLU will push out — to an expanded audience — my argument that we should all be more active and conscientious consumers of prison imagery. My thanks to Matthew Harwood for the questions.

10, 11, 12, 13 & 14. © Steve Davis.

TRY YOUTH AS YOUTH

Currently on show at David Weinberg Photography in Chicago is Try Youth As Youth (Feb 13th — May 9th), an exhibition of photographs and video that bear witness to children locked in American prisons. As the title would suggest, the exhibition has a stated political position — that no person under the aged of 18 should be tried as an adult in a U.S. court of law.

In the summer of 2014, selling works ceased to be David Weinberg Photography’s primary function. The gallery formally changed its mission and committed to shedding light on social justice.

Try Youth As Youth, curated by Meg Noe, was conceived of and put together in partnership with the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. Here’s art in a gallery not only reflecting society back at itself, but trying to shift its debate.

The issue is urgent. In the catalogue essay Using Science and Art to Reclaim Childhood in the Justice System, Diane Geraghty Professor of Law at Loyola University, Chicago notes:

Every state continues to permit youth under the age of 18 to be transferred to adult court for trial and sentencing. As a result, approximately 200,000 children annually are legally stripped of their childhood and assumed to be fully functional adults in the criminal justice system.

This has not always been the case in the U.S. It is only changes to law in the past few decades that have resulted in children facing abnormally long custodial sentences, Life Without Parole sentences and even (in some states) the death penalty. In the face of such dark forces, what else is art doing if it is not speaking truth to power and challenging systems that undermine democracy and our social contract?

Noe invited me to write some words for the Try Youth As Youth catalogue. Given Weinberg’s enlightened modus operandi, I was eager to contribute. Here, republished in full is that essay. It’s populated with installation shots, photographs by Steve Davis, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, and video-stills by Tirtza Even.

–

Scroll down for essay.

–

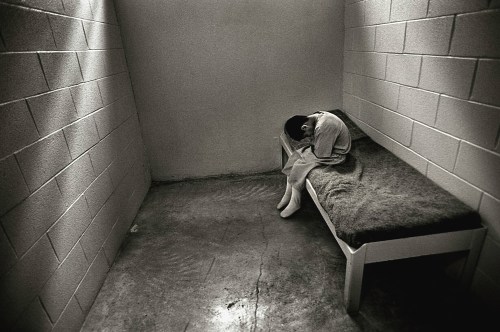

Image: Steve Liss. A young boy held and handcuffed in a juvenile detention facility, Laredo, Texas.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Image: Steve Liss. Paperwork for one boy awaiting a court appearance. How many of our young “criminals” are really children in distress? Three-quarters of children detained in the United States are being held for nonviolent offenses. And for many young people today, family relationships that once nurtured a smooth process of socialization are frequently tenuous and sometimes non-existent.

–

Try Youth As Youth Catalogue Essay

–

WHAT AM I DOING HERE?

–

Isolated in a cell, a child might wonder, “What am I doing here?” It is an immediate, obvious and crucial question and, yet, satisfactory answers are hard to come by. The causes of America’s perverse addiction to incarceration are complex. Let’s just say, for now, that the inequities, poverty, fears and class divisions that give rise to America’s thirst for imprisonment have existed in society longer than any child has. And, let’s just say, for now, that the complex web of factors contributing to a child’s imprisonment are larger than most children could be expected to understand on a first go around.

As understandable as it might be children in crisis to ask “What am I doing here?” it should not be expected. Instead, it is we, as adults, who should be expected to face the question. We should rephrase it and ask it of ourselves, and of society. What are WE doing here? What are we doing as voters in a society that locks up an estimated 65,000 children on any given night? In the face of decades of gross criminal justice policy and practice, what are we doing here, within these gallery walls, looking at pictures?

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility, Albany, Oregon, by Richard Ross. “I’m from Portland. I’ve only been here 17 days. I’m in isolation. I’ve been in ICU for four days. I get out in one more day. During the day you’re not allowed to lay down. If they see you laying down, they take away your mattress. I’m in isolation ‘cause I got in a fight. I hit the staff while they were trying to break it up. They think I’m intimidating. I can’t go out into the day room; I have to stay in the cell. They release me for a shower. I’ve been here three times. I have a daughter, so I’m stressed. She’s six months old. At 12 I was caught stealing at Wal-Mart with my brother and sister. My sister ran away from home with a white dude. She was smoking weed, alcohol. When my sister left I was sort of alone…then my mother left with a new boyfriend, so my aunt had custody. She’s 34. My aunt smoked weed, snorts powder, does pills, lots of prescription stuff. I got sexual with a five-year-older boy, so I started running away. So I was basically grown when I was about 14. But I wasn’t doing meth. Then I stopped going to school and dropped out after 8th grade. Then I was in a parenting program for young mothers…then I left that, so they said I was endangering my baby. The people in the program were scared of me. I don’t know what to think. I was selling meth, crack, and powder when I was 15. I was Measure 11. I was with some other girls — they blamed the crime on me, and I took the charges because I was the youngest. They beat up this girl and stole from her, but I didn’t do it. But they charged me with assault and robbery too. This was my first heavy charge.” — K.Y., age 19.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

I have spent a good portion of the past six-and-a-half years trying to figure out just what it is that images of prisons and prisoners actually do. Who is their audience and what are their effects? If I thought answers were always to be couched in the language of social justice I was soon put right by Steve Davis during an interview in the autumn of 2008.

“People respond to these portraits for their own reasons,” said Davis. “A lot of the reasons have nothing to do with prisons or justice. Some people like pictures of handsome young boys — they like to see beautiful people, or vulnerable people, whatever. That started to blow my mind after a while.”

My interview with Davis was the first ever for the ongoing Prison Photography project. It blew my mind too, but in many ways it also prepared me for the contested visual territory within which sites of incarceration exist and into which I had embarked. Davis’ honesty prepared me to face uncomfortable truths and perversions of truth. It readied me for the skeevy power imbalances I’d observe time and time again in our criminal justice system.

The children in Try Youth As Youth may be, for the most part, invisible to society but they are not far away. “I was just acknowledging that this juvenile prison is 20 miles from my home,” says Davis of his earliest motivations. If you reside in an urban area, it is likely you live as near to a juvenile prison, too. Or closer.

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Prisoners, and surely child prisoners, make up one of society’s most vulnerable groups. Isn’t it strange then that rarely are they presented as such? Often depictions of prisoners serve to condemn them, but not here, in Try Youth As Youth.

As we celebrate the committed works of Steve Davis, Tirtza Even, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, we should bear in mind that other types of prison imagery are less sympathetic and that other viewers’ motives are not wed to the politics of social justice. A picture might be worth a thousand words, but it’s a different thousand for everyone. We must be willing to fight and press the issue and advocate for child prisoners. Our mainstream media dominated by cliche, our news-cycles dominated by mugshots and the politics of fear, and our gallery-systems with a mandate to make profits will not always serve us. They may even do damage.

Image: Steve Davis. A girl incarcerated in Remann Hall, near Tacoma, Washington State.

Given that the works of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross circulate in a free-world that most of their subjects do not, it is all our responsibility to handle, contextualize and talk about these photographs and films in a way that serves the child subjects most. It is our responsibility to talk about economic inequality and about the have and have-nots.

“No child asks to be born into a neighborhood where you can get a gun as easily as a popsicle at the convenience store or giving up drugs means losing every one of your friends,” said Steve Liss “They were there [in jail] because there was no love, there was no nourishing, there was anger in startling doses, and there was poverty. Tremendous poverty.”

Image: Steve Liss. Alone and lonely, ten-year-old Christian, accused of ‘family violence’ as a result of a fight with an abusive older brother, sits in his cell.Every day the inmates get smaller, and more confused about what brought them here. Psychiatrists say children do not react to punishment in the same way as adults. They learn more about becoming criminals than they do about becoming citizens. And one night of loneliness can be enough to prove their suspicion that nobody cares.

Davis, Even, Liss and Ross understand the burden is upon us as a society to explain our widespread use of sophisticated and brutal prisons more than it is for any individual child to explain him or herself. The image of an incarcerated child is an image not of their failings, but of ours. We must do better — by providing quality pre and post-natal care for mothers and babies, nutritious food, livable wages for parents, and support and safety in the home and on the streets. Most often, it is a series of failures in the provision of these most basic needs that leads a child to prison.

“Poverty would be solved in two generations. It would require an enormous change in our priorities. Look at how we elevate the role of a stockbroker and denigrate the role of a school teacher or a parent, those who are responsible for raising the next generation of Americans,” says Liss.

(Top to Bottom) Installation shot; video still; and drawings from Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez’s Natural Life, 2014.

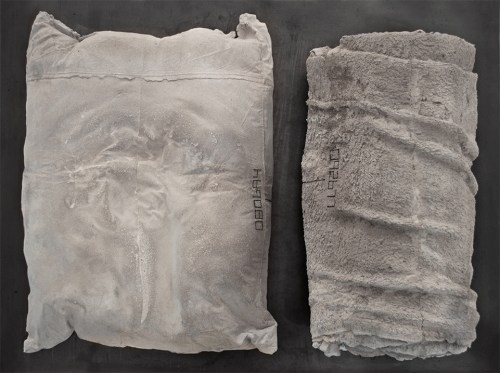

Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez. Natural Life, 2014. Cast concrete (segment of installation). A cast of five sets of the standard issue bedding (a pillow, a bedroll) given to prisoners upon their arrival to the facility, are arranged on raw-steel pedestals in the area leading to the video projection. The sets, scaled down to kid size and made of a stack of crumbling and thin sheets of material resembling deposits of rock, are cast in concrete. Individually marked with the date of birth and the date of arrest of each of the five prisoners featured in the documentary, they thus delineate the brief time the inmates spent in the free world.

Each of the artists in Try Youth As Youth have seen incredible deprivations inside facilities that do not — cannot — serve the needs of all the children they house. Ross speaks of a child who has never had a bedtime. A social worker once told Davis of one child in the system who had never seen or held a printed photograph.

Documenting these sites is not easy and brings with it huge responsibility. Tirtza Even has grappled with the weight of her work “and how much is expected from them is a little heavy.” In some cases, these artists are the outside voice for children. Liss acknowledges that expectations more often than not outweigh the actual effects their work can have.

“People ask how do you get close to kids in a facility like that. That isn’t the problem. The problem is how do you set up enough artificial barriers so you don’t get too close. So you’re not just one more adult walking out on them in the final analysis,” he says. “I, at least, convinced myself into thinking it was therapeutic for the kids. At least someone was listening to them.”

So far, the efforts of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross have been recognized by those in power. Liss’ work has been used to lobby for psych care and an adolescent treatment unit in Laredo, Texas. Ross’ work was used in a Senate subcommittee meeting that legislated at the federal level against detained pre-adjudicated juveniles with youth convicted of committed hard crimes.

“That’s a great thing for me to know that my work is being used for advocacy rather than the masturbatory art world that I grew up in,” says Ross.

Sedgwick County Juvenile Detention Facility, Wichita, Kansas, by Richard Ross. “Nobody comes to visit me here. Nobody. I have been here for eight months. My mom is being charged with aggravated prostitution. She had me have sex for money and give her the money. The money was for drugs and men. I was always trying to prove something to her…prove that I was worth something. Mom left me when I was four weeks old — abandoned me. There are no charges against me. I’m here because I am a material witness and I ran away a lot. There is a case against my pimp. He was my care worker when I was in a group home. They are scared I am going to run away and they need me for court. I love my mom more than anybody in the world. I was raised to believe you don’t walk away from a person so I try to fix her. When I was 12 my mom was charged with child endangerment. I’ve been in and out of foster homes. They put me in there when they went to my house and found no running water, no electricity. I ran away so much that they moved me from temporary to permanent JJA custody. I’m refusing all my visits because I am tired of being lied to.” — B.B., age 17.

Richard Ross’ works in the Try Youth As Youth exhibition at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

The walls of David Weinberg are not the end point of these works’ journey. An exhibition is not a triumph it is a call to action. The work begins now.

Programming during the exhibition — phone-ins to prison, discussions with ACLU lawyers and experts in the field, conversations with formerly incarcerated youth — will all direct us the right way. The gallery space works best when it sutures artists’ creative processes into a larger process that we can shape as socially informed citizens. Our process of building healthy society.

“Kids need us,” says Liss. “They need our time, they need our involvement, and they need our investment. If you own an automotive shop, open it up to kids and the community. It does take a community.”

There are a host of wonderful arts communities doing work, here in Chicago, around criminal justice reform and social equity — Project NIA, 96 Acres, AREA, Prison + Neighborhood Art Project, Lucky Pierre and Temporary Services to name a few.

The arts can trail-blaze the conversation we need to be having. Photography and film are the ammunition with which we arm our reform arguments. First we see, then we do. If art is not speaking truth to power, then really, what are we doing here?

–

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

–

David Weinberg Photography is at 300 W. Superior Street, Suite 203, Chicago, IL 60654. Open Mon-Sat 10am-5pm. Telephone: 312 529 5090.

Try Youth As Youth is on show until May 9th, 2015.

–

Text © Pete Brook / David Weinberg Photography.

Images: Courtesy of artists / David Weinberg Photography.

IS THE INTERNET BECOMING LESS SNARKY?

Portraits of incarcerated youth made by Steve Davis were published on BuzzFeed yesterday. That they are featured does not surprise me; no, it is the reasonable comments that follow that surprise me.

They internet, a space known to often bring out the worst in people has had a special place for trolls as far as images of American prison and prisoners are concerned. Often photographs themselves are bypassed in discussion in order for commenters to shortcut straight to their long held positions — by they left or right, sympathetic or not, nuanced or short-sighted, familiar or prejudiced. Prisons are a divisive issue and often people miss the point of prison photographers who, in the first instance at least, are merely trying to hold a mirror to a system. In this case, Davis holds a mirror to a nation that locks up 65,000 youth on any given night at a cost of $5billion per year.

In my own prejudice, I would’ve expected THE INTERNET + BUZZFEED + KIDS IDENTIFIED AS CRIMINALS would be an equation for vitriol. Not so.

Why would I be so pessimistic? Well, despite BuzzFeed founder Jonah Peretti’s insistence that serious, longform news can exist beside listicles — and despite recent pieces — on last meals of the executed, a trans-activist transforming a prison from within, reflections on wrongful conviction, and the shacking of women prisoners in labor — BuzzFeed content still leasn heavily on shock, innumerable pet vids, “27 things you only know if…” nonsense, and flashes of celeb flesh. The lowest denominators remain our and BuzzFeed’s bread and butter.

All that said, let’s just be thankful for this comment thread:

Some of these faces are so hard. Some are bewildered. And some are just heartbreaking. So beautiful and tragic.

Each one of these faces should never have ended up there. Their incarceration marks the failure of society to raise contributing citizens.

That would imply that society failed every person who has made bad choices. That’s simply not a generalization that pans out entirely. I don’t disagree that we have failed many of these faces as a society, just the generalization.

Look to the parents. Well, perhaps they are/were also incarcerated. Sad all around.

There needs to be a better solution to helping these kids achieve more in life. Yes punish them for their crimes but surely there is better way! Locking them up like this gives them no hope of something better! Nobody but them know the full story so why jump to saying they “deserve” it? some of these kids have been failed by family, peers, society which has resulted in this! Tragic!

I think we should look to the systems used in Scandinavian countries — humane prisons, lots of community service, a focus on rehabilitation, not punishment. …Or we could just stop monetizing the prison system, that would help.

The system makes money off of these children, and I guarantee you there is not one child in there whose parents have a little bit of money! Our prisons are filled with poor people! Justice is definitely not blind!

I can see where you’re coming from, but in my personal experience (two relatives that have been incarcerated both as youth and as adults), there are individuals who will, regardless of the number of chances given, continue to make the wrong choices. You can not force, coerce, or convince someone to act and live as you see fit. They will make choices of their own. These are individuals that do, in fact, deserve the punishments they receive. Like you said only they know the whole story, but regardless of that fact, there are some choices that incarcerated individuals have made that have impacted the lives of innocent people. Do those choices, then, not merit the fullest punishment?

I DO, however, believe there are also individuals who can be guided into a better life because they’ve only known one way. These are the individuals that CHOOSE to make themselves better, both in their own eyes and in societies eyes. They make the choice, and seek out those that can help guide them.

One summer in college, I had an internship in WA for an office of juvenile probation. I went to one of these places with one of the counselors because one of the kids was going to be getting out soon and heading home. This kid was probably 14 or 15 and I remember him sitting there crying because he didn’t want to leave. He had been in out of the system for years and I remember him telling us that no matter how bad it was there, he knew he was going to get fed and have a place to sleep. He told us that he was going to do something as soon as he got out that would send him back. It was tragic on so many levels. Everyone had just given up on this kid and he had pretty much given up on himself.

Locking up a young person in prison is always a shocking and sad thing, but what concerns me is people’s knee jerk reaction that all youth incarceration reflects society’s ultimate failure. Remember, most of you are also the same people who regularly rage against the violent and intolerable stories we read about rape and murder that we regularly see on this site. There are thousands of teenagers (perhaps some of the faces you are seeing here) who are guilty of these crimes. Are you saying that we needn’t incarcerate minors who commit violent crime? Should these individuals only be counseled then allowed to return into society? Despite the fact that several here have unilaterally declared that each of these incarnations are the wholesale fault of society’s failure?

But our prisons out not filled to the brim with people who have committed the kinda of crimes you speak of, and THAT is the failure.

I work in the teen department of my library system, and every librarian takes turns to go visit our JDC to talk to the kids there and find books for them in the collection we maintain at the facilities for them. It’s hard seeing them…especially when they’re super young (I swear a couple I’ve seen couldn’t be older than 11), or especially when you’ve helped them in your branch before. It sucks, and I just always hope that they can come around and learn from the experience and never become a repeat offender.

I have a serious problem with photographers leaving their [captioning on] photos blank when it comes to picturing at risk groups. Each has their own valuable story to tell and name. They are not just “black kids: or troubled youths or street punks etc…the categories that pop up due to the viewers own prejudices. We live in a fucked up world. Such photography should be there to give names to the victims and not participate in their being reduced to a number in the “incarceration game.”

Perhaps the Facebook-linked comment board has sophistication to remove idiot comments and promote those exhibiting most human thought?

Internet, you have my faith again.

Even the commenter that wonders about an anonymous portrait showing a youth with painted nails and foolishly labels the child as possibly “a fabulous homosexual” goes on to demonstrate a knowledge of the system that is unable to adequately care for LGBQIT youth; “In adult prisons obviously gay or transgendered individuals are usually put in solitary confinement for their own protection.” We know that is an unacceptable situation. LGBQIT prisoners are denied access to programming because prisons cannot guarantee their safety in general population.

Unfinished: Incarcerated Youth

Steve Davis is currently taking pre-orders for a book of his photographs from Washington State juvenile prisons, titled, Unfinished: Incarcerated Youth.

You can preorder with Minor Matters Books.

MEETING THE PRISONER CLASS IN POLAND

One might argue that, in the world, there are as many reasons for making an image as there are images. Polish photographer Kamil Śleszyński was curious about how prisoners thought about freedom and “why many prisoners couldn’t live outside [of prison] and would come back again.”

Carrying a camera along with you in these inquiries may or may not help you find answers, but in any case you’ve some images to reflect upon, to lean on, and to mold toward some sort of conclusion.

Śleszyński reached out to me and shared his project Input/Output, which consists of photographs made within a prison and in a re-entry centre that supports ex-prisoners. Both facilities are in the city of Bialystok. The images were made between September 2014 and February 2015.

Using a limited number of sheets of 4×5 film forced Śleszyński to be selective with his exposures. The majority are posed portraits. I wanted to find out what he discovered during the project.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Click any image to see it larger.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): In the intro text to Input/Output you suggest that prisoners are institutionalized and are bound by what they learn in prison. Can you explain this more?

Kamil Śleszyński (KS): The man who goes to prison needs to adjust to the rules prevailing there. On the one hand, the rules are created by the Polish prison system, on the other hand by the prisoners themselves.

For example, Grypsera is a prison subculture. Those prisoners who adhere it rules are known as Grypsera too. They have own language which is based on polish language. Grypsera was created in the past century and determined the tough rules, hierarchy and standards. Today, these rules have loosened somewhat but many of them are still alive.

The prison environment is permanently stigmatising. This is perfectly illustrated by words from the book “The Walls of Hebron” written by Andrzej Stasiuk: “To the prison you go only one time. This first. After that, there is no prison. There is no freedom too. All things are the same.”

Polish prisoners are not taught independence because it is not technically possible within their reality. Resocialization is a key issue, but most progams toward it are not enough. Therefore, freed prisoners cannot deal with freedom itself. It is easier to get back behind bars where everything is either black or white.

PP: Many of your subjects have tattoos. Are tattoos important in Polish prisons?

KS: Tattoos were an important element of prison subculture. Tattoos on their faces and hands allowed quickly define the criminal profession. Military ranks tattooed on their arms, define the length of the sentence. There were a lot of different types of tattoos. Only deserving criminals could have it.

Today, these rules are loosened. Tattoos do not always have the prison symbolism, sometimes are associated with religion.

PP: You shot in a prison in Bialystok. What is its reputation?

KS: The closed wards were the worst, because prisoners are spending 23 hours a day in a cell. Prisoners can be a little crazy as a result.

PP: Why did you want to photograph inside?

KS: I grew up in the neighborhood of the prison. Often I was walking near by the prison walls and watching prisoners. They were standing in the windows bathing in the sun. I was wondering why they were behind the walls. This curiosity stayed with me.

PP: How did you get access?

KS: The year ago I met director and journalist Dariusz Szada-Borzyszkowski. He was working with a prisoners. He cast them in performances. He put me in touch with the right people and gave valuable hints. His help greatly accelerated my work.

PP: What were the reactions of the staff?

KS: Prisoner chiefs had a positive attitude to the project. In one of the prison facilities I had a lot of creative freedom.

PP: What were the reactions of the prisoners?

KS: Gaining the confidence of prisoners takes a long time, and this was a key issue for the project. Prisoners are understandably distrustful — they’re afraid that someone from the outside can deceive or ridicule them.

One of the prisoners told me that he don’t want to work with me because prisoners are not monkeys in a cage. I spent a lot of time to convince him that I wouldn’t misrepresent him. In the end, he was involved in the project so much that he convinced other prisoners to cooperation with me.

I was shooting with an old camera 4×5. Many of prisoners were interested in my shooting technique because they had never seen such equipment. It was a new experience for them.

PP: Did the prisoners have an opportunity to have their photograph taken at other times?

KS: Prisoners are photographed by the staff upon entry into the prison and at the time of their departure. During imprisonment is not possible to be photographed … unless they are involved in a project like mine.

PP: Did prisoners have photographs in their cells?

KS: Sometimes prisoners have photos of their loved ones in their cells. This helps to survive in isolation.

PP: Did you give prisoners copies of your images?

KS: Prisoners are collaborating when it is profitable. The photos were a reward for participating in the project. Many of them sent photos to their loved ones.

PP: What do people in Poland think about the prison system? And of think prisoners?

KS: People don’t know much about prisons and prisoners, and guided by stereotypes. They want to know how it is inside, but do not want to have anything to do with the prisoners. They are afraid of them.

I hope that such projects like mine, will help to change those points of view. I got scholarship from the Marshal of Podlaskie region for the preparation of a draft photo book about the prisoners. It wasn’t easy, but the scholarship suggests to me that views are slowly changing.

PP: Overall, is the Polish prison system working or not? Does it keep people safe, or rehabilitate, for example?

KS: The polish prison system puts too little emphasis on resocialization.

PP: Thanks, Kamil.

KS: Thank you, Pete.