You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Press’ category.

Above is a quote from a US marine asking how Iraqis would react to disclosure of the Baghdad Canal murders.

I talked two days ago by alleged British Army abuses in Iraq. Today I want to draw attention back to the crimes of the American military. Under the Freedom of Information Act, CNN has got hold of 23 hours of interrogation tapes that detail the actions and motives of US marines that killed three Iraqis, dumping their bodies in a Baghdad canal. A group of soldiers were present for the executions; three soldiers were sentenced, each for 20 years or more. Sgts. Mayo, Leahy and Hatley are each appealing their convictions.

In analysis of the new information on these tapes, CNN’s Anderson Cooper focuses on the soldiers motives. Frustrating military policy is cited as a contributing factor in the soldiers’ decisions to murder. The soldiers balked at the impossible steps needed to prove a crime and continue detention of Iraqis. Soldiers were convinced that (after inevitable release) prisoners would returns to the streets, return to arms and fire upon the US military once more.

You can read the full analysis from CNN here. It includes a slideshow with photos of the canal, map of the area, photos of the military prison in Germany where the three soldiers are held and portrait shots of the men and (separately) their wives.

It was the portraits of the wives that intrigued me. Firstly, because they weren’t something I expected to see, and secondly because I they are so similar to images of grieving family members. Not surprisingly, the wives consider their husbands heroes and not killers; they campaign for their release.

I conclude that military families can lose their loved ones in circumstances other than death in the field.

___________________________________________________________

Photos: From top, clockwise © Johanna Mayo, Rich Brooks/CNN; Kim Hatley, Rich Brooks/CNN; Jamie Leahy Derek Davis/CNN

On Will Steacy’s blog this week:

Silverstein pulled a nearly foot-long knife from his conspirator’s waistband.“This is between me and Clutts,” Silverstein hollered as he rushed toward him. One of the other guards screamed, “He’s got a shank!” But Clutts was already cornered, without a weapon. He raised his hands while Silverstein stabbed him in the stomach. “He was just sticking Officer Clutts with that knife,” another guard later recalled. “He was just sticking and sticking and sticking.” By the time Silverstein relinquished the knife—“The man disrespected me,” he told the guards. “I had to get him”— Clutts had been stabbed forty times. He died shortly afterward.”

David Grann. ‘The Brand’, The New Yorker, February 23rd, 2004

It may be helpful for my readership if I state that I am not a prison abolitionist.

It occurred to me that I may not have shared that with you. There is a legitimate need for prisons when incorrigible and dangerous men or women must be controlled for the safety of all.

Unfortunately, over the past three decades, prisons in America have been used to test the “incapacitation theory” – which as Ruth Gilmore posits in Golden Gulag is not much of a theory, in fact it is not really a theory because it doesn’t propose to do or enact much at all [I paraphrase].

Prisons are many things; the parts of an expensive social experiment, the dumping-grounds for citizens caught up in the war on drugs; the accidental and damaging substitutions for mental health institutions; and in very few (and just as real) circumstances the necessary lock-ups for extremely violent offenders.

One problem I have in communicating the need for real prison reform is created by the fact that violent offenders are those that seize the public’s attention. Violent criminals are a tiny fraction of America’s prison population yet they’re the ones that trigger fear instincts and sway public opinion. I understand why this is the case and why it takes a lot to get past that.

Men like Silverstein, who’s actions are described above, should be behind bars for a long, long time. But the vast majority of the 2.3 million prisoners of the US are not like Silverstein. This same vast majority would also want Silverstein behind bars … and they’d make good argument as to why they shouldn’t be there with him.

Often it seems photographs of South American prisons are presented in North American media only to emphasise the gulf that exists between the conditions of incarceration in the two regions.

I have posted before about prison beauty pageants in Bogota, Colombia; about the rise and fall of prison tourism at San Pedro in La Paz, Bolivia, and I have looked twice at Gary Knight‘s photography at Polinter prison in Rio de Janeiro – latterly featuring the conspicuous acts of a celebrity evangelical minister.

(Nearly) all photo essays I see coming out of prisons in South or Central America fall into one of two categories, or both:

1) A colourful contradiction to the dour, authoritarian environments depicted in US prison photojournalism.

2) A claustrophobic assault on our emotions as witnesses to desperate overcrowding and poor hygiene. The example par excellence of this is Marco Baroncini’s series from Guatemala.

What leads me to a narrow, ‘boxed’ categorisation of such documentary series is that I am convinced photographers know either the media or their editors well enough to know what flies with Western consumers and as such deliver an expected aesthetic.

I was therefore left without anchor when cyber-friend Nick Calcott sent over this latest offering by GOOD magazine on Medellin’s prison in Colombia. The images are by the inmates themselves:

On the invitation of the Centro Colombo Americano, an English language school for Colombians in Medellín, Vance Jacobs ventured to the Bellavista Prison with an inspired assignment: to teach documentary photography to eight inmates in one week.

“One of the things that gets the inmates’ attention is responsibility, that there is a stake in what they do. In this case, their ability to work together as a team, and to pull this together in a very short amount of time would determine whether other similar projects were done not only at this prison but at other prisons in Colombia,” says Jacobs. “Once they bought into the idea that there was a lot at stake, they really applied themselves.”

In the past, I have wondered how the camera can be used as a rehabilitative tool and it is a question that can be answered from different angles. In this case the responsibility given to the inmates is how we can derive worth. I have shown before that performance and team work in front of a camera can be good for exploring the self and ones own identity (and the results are of huge intrigue). The common denominator for any photography project is surely that it immediately relieves the boredom of incarceration.

In the past I have provided varied perspective on Guantanamo. I put together a rudimentary Directory of Visual Resources. I alerted readers to important coverage of exceptional events here and here (granted, all events related to Gitmo are out of the extraordinary) and I have provided reflection on Guantanamo through the lenses of Bronstein, Clark, Gilden, Linsley, Pellegrin, Toledano and Lieutenant Sarah Cleveland.

Ultimately, none of these posts come close to describing or making sense of that most nonsensical of places. And so to ACLU’s latest video. My good mate Stan (cheers pal) posted earlier today:

Elsewhere, a friend of Prison Photography alerted me to the online journal JumpCut. Julia Lesage has assembled the most comprehensive webpage of Guantanamo links I’ve ever come across. Some of the links are already 404, but I would encourage you to peruse – I have still not exhausted the many resources. Leasge also contributes to the Spring 2009 issue with a section on ‘Documenting Torture’.

Past and present ruminations about what is and isn’t a photograph have been a source of frustration for me. For one, people can draw whatever lines they wish to determine the point at which manipulation tricks out a photograph and thus qualifies it as photo-illustration. And for another, as Errol Morris keeps banging on about, ALL photography is lies (and manipulation).

These debates are not about truth. Interventions – power relations, habit, photographic custom, complicity among subjects, props, political agendas (and framing), cropping, tweaking of exposure levels before and after development, digital alterations – mean that photography can never be, will never be truthful.

People forget that often it is the ingenious tricks that have spurred the largest wonder among viewing public – think Oscar Rejlander’s Two Ways of Life, Spirit Photography and – in a different sense – Ansel Adams’ Zone System.

It is therefore, with some relief that an artist like Azzarella comes along using photo-manipulation as the tactic and purpose for his work.

Last week, I questioned Anton Kratochvil’s Homage to Abu Ghraib, mainly because I think it makes little contribution to the discourse on the political aesthetics of Abu Ghraib. The blurry references to torture in Kratochvil’s images are in response only to a personal, conscious and willing point of view. I understand that Kratochvil’s work was an exercise in self-therapy but that shouldn’t stop me comparing it to Azzarella’s broader concerns about more general and unconscious reactions to well-circulated images.

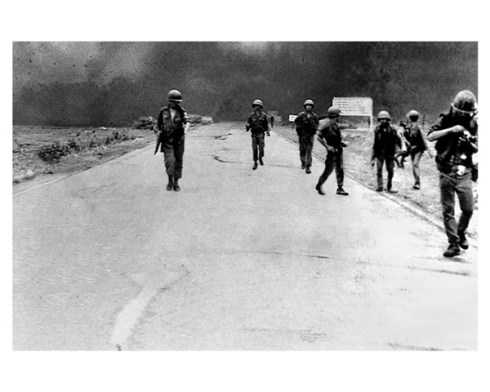

If I w re to wr t th s sent nce wi h lette s m ss ng, you can still read it. The human brain is a wonderful instrument drawing on past experience to quickly filter out the non-possibilities. Just as the brain instantaneously deciphers gaps in text so it does with gaps in images.

With every passing hour the Spectacle suffuses itself further. It isn’t so much us reading images but images reading us. Our involuntary responses to images are predictable, predicted, precoded. The redacted action of violence in Azzarella’s pictures plays second fiddle to the original image, for it is the original image we drooled over and devoured.

The hooded detainee, dead student, wailing child or falling soldier needn’t even be present; our internal, emotional feedback spun by these images will forever be the same. We fill in the gaps and short circuit to prescribed disgust, sadness and politics, thus confirming our prevailing bias.

Azzarella’s works expose the fraud in us all … and our cheapened, robotic response to image.

ALL IMAGES © JOSH AZZARELLA. FROM TOP TO BOTTOM: UNTITLED #13 (AHSF); UNTITLED (SSG FREDERICK); UNTITLED #24 (GREEN GLOVES); UNTITLED #35 (CAFETERIA); UNTITLED #39 (265); UNTITLED #20 TRANG BANG; UNTITLED #43 (PAR115311).

Too Much Chocolate

When Jake Stangel put out a call to interview Damon Winter for Too Much Chocolate I didn’t hesitate. How often do you get to bend the ear of a Pulitzer Prize winning photographer?

Jake assured me that Damon was – is – “a super-nice guy” as well. I might argue that Damon is too nice; he carried, without complaint, a sinus-busting cold to deliver the interview.

Damon and I spoke about his assignments in Dallas, L.A. and New York, the Obama campaign coverage, making portraits, Dan Winters, Irving Penn and Bruce Gilden. Read the full interview here.

_____________________________________________________________

Angola Rodeo

Not without my own agenda, I also asked Damon about his experience down at the Angola Prison Rodeo:

PP: Why were you there?

DW: I had gone out for two trips. It was when I worked at the Dallas Morning News. The way I pitched it was that the prison was expanding the program to launch a spring rodeo. I wanted any excuse I could get to go down there and photograph. It sounded absolutely incredible.

DW: And the paper ended up not being that interested. They may have run a small little blurb about it, but I did it for my own interest. It was fascinating – a completely wild situation. Most of these guys came from the cities. Some had never even seen a cow let alone roped a horse.

PP: Describe the atmosphere.

DW: The closest thing to modern day gladiators – something you’d see in a Roman Coliseum. The crowd is chanting for blood, they want to see a violent spectacle where prison inmates are the subjects. It’s the same reason people go to see a horror movie or stare at a wreck on the highway. It is a very strange situation but they want to see blood.

PP: Do you think it helpful to the local community?

DW: There is no interaction between public and inmates. The public is there to observe and the inmates are there to entertain. The benefit the inmates gain is at a level very specific to their situation. They risk injury being in the ring with massive bulls, and their prize is something I think anyone in the free world would laugh at, you know? Maybe a couple hundred bucks. But it is substantial in their environment.

It speaks to the bleak situation that those guys are in that this would be enticing – to risk bodily harm for a couple of hundred dollars.

I don’t know how constructive it is for relations between prison and non-prison populations.

PP: Which is unusual because in any other state across the country, there is no interaction between the public and the incarcerated population.

DW: What’s your feeling?

PP: I think it builds a division at a local level, but it also feeds a national view that excludes the realities of prisons. The inmates are put out there to be observed, photographed and consumed. Such a presentation is not unpalatable to the American public. To the contrary, the public feels as though it gains from it. I think here unexamined (and abusive) interactions can be confused with relationships.

I think the wasteful and very boring reality of prisons in America is not going to make it into newspapers or media, but the rodeo does. It skews perception. I think the rodeo is problematic.

DW: I felt the event was dehumanizing. It was done in a manner so that the inmates are reduced to the level of the beasts they are competing against. It seems the field has been leveled between animals and inmates and the feeling that you get from that is that they themselves are like animals. They are not seen terribly differently from the way that the animals are seen.

PP: I am not sure that that sort of spectacle would take place outside of Louisiana, certainly outside the South. Granted, Angola’s warden Burl Cain jumps at the chance to get the cameras in at any opportunity.

DW: Yes, I saw The Farm, a documentary filmed at Angola.

PP: I think Cain’s administration paired with the history of the event creates a spectacle at the rodeo that goes unexamined.

PP: Cameras are common at Angola; documentary shorts on the football team and photo essays on the hospice. It is a complex that has 92% of its population.

DW: You should look at Mona Reeder’s work. She works at the Dallas Morning News. I think it was called The Bottom Line and she turned the stats into photo essays and one of the stats was the number of prisoners in juvenile facilities. She got some pretty good access. She received a R.F. Kennedy Award.

PP: I certainly will. Thanks Damon.

DW: Thank you.

_____________________________________________________________

Below are three of Damon’s photographs from Afghanistan which stopped me in my tracks. Unfortunately, I discovered them after the interview so didn’t get Damon’s take on them.

The images of the boys really affected me. We see so many images of bearded men, U.S. Marines in the dirt, explosions, women in burqas, etc, but it is the children of Afghanistan who will carry the violent legacy for the longest. What pictures reflect that fact?

It is an impossible task of any image to near ‘truth’ or reality, but these two pictures get very close to the sad reality of conflict and the impressionability of youth.

3,000 inmates die of natural causes in US prisons each year. If they are fortunate, they will do so in a prison hospice. The New York Times’ John Leland reports on this growing sector of corrections provision. Fred R. Conrad provides the photography.

The story focuses on the relationships between the dying men and the inmate volunteers who tend to their needs in the final days, weeks, months.

Coxsackie Correctional Facility, NY, featured in the NYT audio slideshow is one of 75 prisons across the nation that has developed hospice programs for geriatric and dying inmates.

___________________________________________________________

Related: Lori Waselchuk has won the admiration of the photographic community for her series Grace Before Dying which surveys the prison hospice at Angola, Louisiana. More on Waselchuk to come.

“The statistics are embarrassing to the state [of Texas]”

Mona Reeder, Poynter Online, May. 20, 2008

41% of children in the juvenile justice system have serious mental health problems. Joseph, 17, got a little bit of sunshine in the yard outside the security unit at Marlin. The facility, which once housed adult prisoners in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Damon Winter recommended the work of Mona Reeder, a former colleague of his at The Dallas Morning News.

Reeder won the ‘Investigative Issue Picture Story’ at the 2008 Best of Photojournalism Awards for The Bottom Line. Through pictures, Reeder explored Texas’ poor rankings in a number of categories including health care, executions, mental health statistics, juvenile incarceration, voter apathy, poverty and environmental protection.

This is not solely a photography project about prisons, and thereby lies its strength. Reeder successfully links the stories of numerous state institutions that are left wanting when put under close examination. It is truly a Texan story for Texan constituents. Reeder explains, “As I was wrapping up a project about homelessness in Dallas, a social worker who had helped me with contacts on the streets handed me a set of statistics issued by the state comptroller’s office ranking Texas with the other states in the U.S.”

Photojournalism was an effective medium for this breadth of information, “This project represented a well-researched, in-depth piece about serious issues affecting the entire state of Texas, and it was presented in an innovative manner that even the busiest person could get through and absorb in a relatively short amount of time” states Reeder.

60% of children under the Texas juvenile prison system come from low-income homes. Texas spends more than twice as much per prisoner as per pupil. Laying on the floor, thirteen-year-old Drake Swist peers out from underneath the bars on his cell door in the security unit of the Marlin facility. Kids get their first glimpse of life in the Texas Youth Commission through the Orientation and Assessment facility in Marlin, Texas.

Mona Reeder has worked on numerous criminal justice issues in Texas, including death row stories and sex-offender rehabilitation.

As well as the BOP (2008), Reeder won a Robert F. Kennedy Award for The Bottom Line. She was interviewed by the Poynter Institute about the project and her approaches to photojournalism.

The Dallas Morning News gave The Bottom Line the full multimedia treatment with an impressive online package featuring eight slideshows of the stories of individuals wrapped up in the statistics. IT’S A MUST SEE.

Texas: First in capital punishment, second in the size of the income gap between rich and poor, and second for the number of people incarcerated. Behind every set of numbers is the possibility that yet another child will live a lesser existence. Does Texas not know what to do, or does it just not care? Texas has the most teen births and the most repeat teen births in the nation, earning a ranking of 50th in the U.S. Barely one day old, Jasmine Williams sleeps on her mother’s lap as they wait for the baby’s paternal grandmother to come and take custody of her. Her mother, Kimberly Williams, 15, is in TYC custody and correctional officers shackled her feet shortly after giving birth to her baby. Both of Jasmine’s parents were 15 when she was born.