You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Visual Feeds’ category.

First Meal: Everything bagel with veggie cream cheese and a medium coffee from Dunkin Donuts. “I was craving a really good bagel,” said Keri Blakinger, 30, who served 21 months in female correctional facilities in NY. Blakinger, a vegetarian, subsisted mostly on canned vegetables and granola bars, which she received in packages from her parents. Since getting out, her diet has not changed much because she grew accustomed to not having to cook for herself. © Julius Motal.

There’s no shortage of projects about meals in the small corner of photographic practice concerned with prisons and human rights. Specifically, the final meals of condemned prisoners have stoked the macabre and outraged intrigue of artists.

Julius Motal‘s photographs of “first meals” are therefore something of a departure and a welcome addition to the visual narratives trying to convey the transitions out of prison and into society. Instead of an end point, Motal suggests a starting point (although the quality of help for reentry is up for question in many jurisdictions). Still, this work is simple and hopeful. Returning citizens cannot make it on their own. They’ll need to carry resolve and hope and see that reflected back from society. Perhaps Motal’s series with its extended captions helps humanise former prisoners?

The startling thing for me is the similarity in the types of food choices made by people about to face execution and people making a more inhibited choice once they’re outside of prison — almost without exception they go for fast food. Do returning citizens opt for fast food because they’re poor, have for the most part been poor, and eaten the cheapest and most accessible food? Or is it more simply a case of reaching out for easy comfort (supposing fast food equates to comfort) in times of relief?

There’s a reflection of class in Motal’s work, which is a good thing. It’s a healthy reminder how the prison industrial complex functions; hoe it brutalises communities of lower economic standing. Very few prisoners are like the middle class, liberal arts college educated Piper Kerman — or the TV show equivalent Piper Chapman — from Orange Is The New Black. Most people going to and leaving prison are poorer than the average American.

Currently, Motal’s series First Meals: This is What Freedom Tastes Like is only six images deep. I hope he’ll extend the survey and continue to ask ex-prisoners about their relationships to food. There’s many different directions in which this work could go not only in terms of interaction with subjects but in terms of public education to tie in with reentry services, food deserts, mother and child nutrition programs, and so on and so forth.

It’s significant that more than one caption refers to the overwhelming choice within — and paralysing nature of — grocery stores for former prisoners who were unaccustomed to variety and decision making power for extended periods. One caption reads:

For Stacy Burnett, the choices at the Burger King in Montrose, PA were overwhelming, so much so that she couldn’t make a decision. “I could feel the energy shift behind me,” Burnett, 39, said of the growing restlessness behind her. She finally told the cashier that she’ll have what the woman ahead of her ordered, which was a whopper, fries, a shake and a soda. For the first six months after her release, going to the supermarket was tremendously difficult. There were simply too many choices, and if she didn’t get anything in the first 10 minutes, she would leave without getting anything.

Last meals are a captivating topic but direct us only to the plight of 3,500ish people on death row in the country. Motals’ work about “first meals” directs us to the tough realities of the millions of people leaving jails and prison every year in America.

Image source: Insouciant Writing

THE WRITING ON THE WALL

If you’re in NYC between now and May 22nd go see The Writing on the Wall, an installation by Hank Willis Thomas and Baz Dreisinger. It opened yesterday at the President’s Gallery at John Jay College.

The Writing on the Wall debuted in September 2014, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit (MoCAD) where it was part of the Peoples’ Biennial.

There’s an opening reception tomorrow night, Weds, April 22nd, from 5:30 to 7:30pm.

THE BLURB

The installation is made from essays, poems, letters, stories, diagrams and notes written by individuals in prison around the world, from America and Australia to Brazil, Norway and Uganda. The hand-written and typed pieces were accrued by Dr. Dreisinger during her years teaching in US and international prisons, in the context of both the Prison-to-College Pipeline program she founded at John Jay and her forthcoming book Incarceration Nations: Journeying to Justice in Prisons Around the World.

On a basic and literal level, The Writing on the Wall is about giving voice to the voiceless and humanizing a deeply de-humanized population. It represents a kind of modern-day hieroglyphics, projecting a hidden world into a very public space and allowing a people too often spoken of and for—by politicians and a punishment-hungry public—to speak for themselves, in the most intimate of ways. It is a tribute to the power of the pen, a deliberate verbal intrusion and an assertion that some words need very much to be seen in order to be heard. Indeed the writing is not just on the wall but on the floor, on every inch of the installation space, such that the viewer, unable to look away, is compelled to confront a crisis: global mass incarceration. The piece thus fittingly references the Biblical story in which the writing on the wall, as interpreted by the prophet Daniel, foreshadowed imminent doom and destruction.

Just as mass incarceration is a living, growing global phenomenon, The Writing on the Wall is an ever-evolving installation. With every iteration, it grows and assumes a new shape, because the documents comprising it—material written by those living behind bars—continue to land in Dr. Dreisinger’s hands and mailbox.

THE BIOGRAPHIES

Hank Willis Thomas is a photo conceptual artist working with themes related to identity, history, and popular culture. He received his BFA from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and his MFA in photography, along with an MA in visual criticism, from California College of the Arts (CCA) in San Francisco. Thomas has acted as a visiting professor at CCA and in the MFA programs at Maryland Institute College of Art and ICP/Bard and has lectured at Yale University, Princeton University, the Birmingham Museum of Art, and the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. His work has been featured in several publications including 25 under 25: Up-and-Coming American Photographers (CDS, 2003) and 30 Americans (RFC, 2008), as well as his monograph Pitch Blackness (Aperture, 2008). He received a new media fellowship through the Tribeca Film Institute and was an artist in residence at John Hopkins University as well as a 2011 fellow at the W.E.B. DuBois Institute at Harvard University. He has exhibited in galleries and museums throughout the U.S. and abroad. Thomas’s work is in numerous public collections including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Guggenheim Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art. His collaborative projects have been featured at the Sundance Film Festival and installed publicly at the Oakland International Airport, the Oakland Museum of California, and the University of California, San Francisco. He is an Ellen Stone Belic Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media, Columbia College Chicago Spring 2012 Fellow.

Baz Dreisinger is an Associate Professor in the English Department at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. She is the founder and Academic Director of the college’s Prison-to-College Pipeline Program (P2CP), which offers credit-bearing college courses and reentry planning to incarcerated men at Otisville Correctional Facility. She is also a reporter on popular culture, the Caribbean, world music, and race-related issues for the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and Wall Street Journal, among other outlets; she produces on-air segments for NPR and is the co-producer and co-writer of the documentaries Black & Blue: Legends of the Hip-Hop Cop, which investigates the New York Police Department’s monitoring of the hip-hop industry, and Rhyme & Punishment, about hip-hop and the prison industrial complex. The author of Near Black: White to Black Passing in American Culture (2008) and the forthcoming Incarceration Nations: A Journey to Justice in Prisons Around the World (2015), Dreisinger earned her Ph.D. from Columbia University and has been a Whiting Fellow and a postdoctoral fellow in African-American studies at UCLA.

THE DETAILS

President’s Gallery, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY 899 10th Avenue, Haaren Hall, 6th Floor , NY 10019.

Hours: 9am-5pm, Mon-Fri.

Contact: gallery@jjay.cuny.edu or 212.237.1439.

GRAVE ISSUE AND A GRAVE VIDEO APPEAL

Prisons are hostile, and potentially lethal, environments for transgender individuals. The acute need for understanding, medical care, and protection from predatory abuse is made visible for us through the remarkable efforts of Ashley diamond, a woman incarcerated in the mens’ Georgia State Prison.

Hearing her case and the evidence put forth by her advocates, The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), it is a wonder Ms. Diamond is still alive. She has suffered no fewer than seven serious sexual assaults in the three years of her term.

Georgia’s prison system is notoriously dysfunctional and brutal. The prison in which Ms. Diamond is incarcerated is Georgia State. It had more sexual assaults between 2009 and 2014 than all but one other state prison. Ms. Diamond’s access to safety is merely one of her request in the recent lawsuit. Mainly, Ms. Diamond asks that her medically diagnosed condition of Gender identity disorder (GID) or gender dysphoria is recognised by the Georgia Department of Corrections and that they provide her the hormones that she was taking for 17 years prior to imprisonment.

Ms. Diamond describes her incarceration to this point as nothing short of torture. Her gender identity is held in contempt by the authorities and her vulnerable situation is in no way accommodated. Bravo to her for forcing a lawsuit against the state in order to secure recognition, medical hormones treatments. This is a fight that will not only elevate the visibility of the severe issues facing LGBQT in prison but may secure human rights hitherto ignored or trampled.

Ms. Diamond and transgender prisoners like her are in a perilous position.

In reporting on the case and the subsequent Federal level support for it, The New York Times says, “Many face rejection by their families, harassment at school and discrimination in the workplace. Black transgender people have inordinately high rates of extreme poverty, homelessness, suicide attempts and imprisonment; nearly half those surveyed for the National Transgender Discrimination Survey had been imprisoned, compared with 16 percent of the study’s 6,450 participants. Transgender women in male prisons are 13 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than is the general population, with 59 percent reporting sexual assaults, according to a frequently cited California study.”

When budgets for non-profit advocacy groups are so scarce and the resources and intractability of the state opposition is so large, media outreach and messaging has to be perfect. Bravo to SPLC for delivering a message in which Ms. Diamond is front and center. From a contraband cellphone, Diamond makes a direct plea to the public. The illicit nature of the act adds a sense of urgency to the appeal. It is as if all other avenues have been cut off and desperate times require desperate measures.

It’s a bold move and possibly not without its consequences. I would not be surprised if the GDOC was to retroactively punish Ms. Diamond for possession and use of a cellphone. Given the daily threat to which Ms. Diamond is subject, it hardly seems sanction for possessing a cellphone would be high on her list concerns. Whatever the extent of “risk” is involved in publishing this cellphone video it is another significant lens through which we can see this case, this story and this political action.

Video still from Ashley Diamond’s prison cell video.

ALLIES

It is also crucial that other prisoners are present in the video. It is empowering to see anonymous prisoners feature as allies and supporters. It balances the narrative of prisoners only being predators. Prisoner-led self-organisation is the most quickly silenced but the most effective of resistance against the state and prison industrial complex. I wonder if videos such as this could potentially add further to future struggles?

A FEW QUICK THOUGHTS ON PRISON VIDS

I’ve been promising myself for years to in some way put together an analysis of contraband cellphone photo and video footage. The only definitive thing I can say is that I’ve not seen the vast majority of it and never will.

99.99% of prisoner made recordings are shared between devices, between loved ones and never uploaded to the internet for public viewing. If they do make it to social media they are on the internet behind passworded social media accounts.

Often when prisoner made cellphone videos emerge it is to villianise the prisoner further. News stories peddle in public consternation — we abhor prisoners who might be seen to be thumbing their noses at authority. We also like to frame the stupid or “foolish criminal” and mock them when their video gets them caught. But the truth is, prisoners are very, very sensible with their videos and digital distributions. Why do you think we see so few prison videos?

Prisoners have an interest in protecting their assets — this applies to cellphones that are expensive to acquire and very, very useful. Prisoners have zero incentive for making it publicly known they have or had have had a cellphone. Most prisoners use cellphones to contact families as a cheaper alternative to a price-gouged market. And, let’s remember that phones — like any contraband — get into prisons through the hands of staff as much as they do because of family visitors or civilians.

If the cellphone becomes an issue for the prison administration then their complete lack of understanding of the complaint is exposed — it’d prove the point being made by Diamond and SPLC that the Georgia DOC has demoted human rights to the point of endangering lives.

SPLC’s strategic use of Diamond’s video testimony is deliberate, timely and well-advised. It accelerated and humanised the issue. I, for one, hope it might be a method repeated in the future to benefit the crucial legal battles of prisoners. If so, it could also change our appreciation of prisoner-led political actions.

If you’re in NYC, get yourself to lower Manhattan tomorrow evening.

Josh Begley is a data artist and web developer, well known for creating an iPhone app to track every reported U.S. drone strike.

In his artist talk ‘Visualizing Carceral Space’, Begley will discuss his projects Prison Map and Dronestream (a.k.a MetaData).

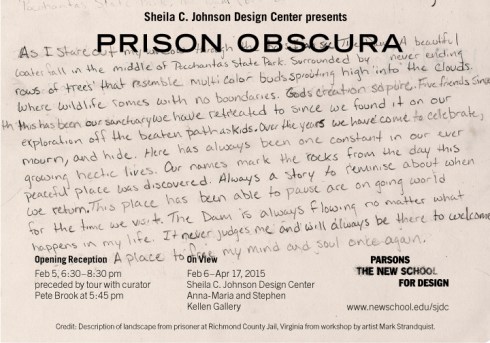

Begley will speak from 6:00 to 7:30 pm, on Thursday March 12th, at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, 2 W13th Street in the ground-floor Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery.

The talk is offered as part of the programming for Prison Obscura showing at Parsons which features an expanded, custom-made version of Prison Map.

Josh Begley‘s work has appeared in Wired, The New York Times, NPR, The Atlantic, New York Magazine, and at the New Museum of Contemporary Art. He currently works at The Intercept doing incredible things like this.

Follow Josh on Twitter at @joshbegley and on @dronestream.

The Big Graph (2014). Photo: Courtesy Eastern State Penitentiary.

Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site Guidelines for Art Proposals, 2016

Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia has announced some big grants for artists working to illuminate issues surrounding American mass incarceration.

READ! FULL INFO HERE

ESP is offering grants of $7,500 for a “Standard Project” and a grant of $15,000 for specialized “Prisons in the Age of Mass Incarceration Project.” In each case the chosen installations shall be in situ for one full tour season — typically May 1 – November 30 (2016).

DEADLINE: JUNE 17TH

THE NEED

ESP has, in my opinion, the best programming of any historic prison site when it comes to addressing current prison issues. Last year, they installed The Big Graph (above) so that the monumental incarceration rates could tower over visitors. Now, ESP wants to explore the emotional aspects of those same huge figures.

“Prisons in the Age of Mass Incarceration will serve as a counterpoint to The Big Graph,” says ESP. “Where The Big Graph addresses statistics and changing priorities over time, Prison in the Age will encourage reflection on the impact of recent changes to the American criminal justice system, and create a place for visitors to reflect on their personal experiences and share their thoughts with others.”

ESP says that art has “brought perspectives and approaches that would not have been possible in traditional historic site programming.” Hence, these big grant announcements And hence these big questions.

“Who goes to prison? Who gets away with it? Why? Have you gotten away with something illegal? How might your appearance, background, family connections or social status have affected your interaction with the criminal justice system? What are prisons for? Do prisons “work?” What would a successful criminal justice system look like? What are the biggest challenges facing the U.S criminal justice system today? How can visitors affect change in their communities? How can they influence evolving criminal justice policies?” asks ESP.

While no proposal must address any one or all of these questions specifically they delineate the political territory in which ESP is interested.

“If our definition of this program seems broad, it’s because we’re open to approaches that we haven’t yet imagined,” says ESP. “We want our visitors to be challenged with provocative questions, and we’re prepared to face some provocative questions ourselves. In short, we seek memorable, thought-provoking additions to our public programming, combined with true excellence in artistic practice.”

“We seek installations that will make connections between the complex history of this building and today’s criminal justice system and corrections policies,” continues ESP. “We want to humanize these difficult subjects with personal stories and distinct points of view. We want to hear new voices—voices that might emphasize the political, or humorous, or bluntly personal.”

GO TO AN ORIENTATION

ESP won’t automatically exclude you, but you seriously hamper your chances if you don’t attend one of the artist orientation tours.

They occur on March 15, April 8, April 10, April 12, May 1, May 9, May 15, June 6.

Also, be keen to read very carefully the huge document detailing the grants. It explains very well what ESP is looking for including eligibility, installation specifics, conditions on site, maintenance, breakdown of funding (ESP instructs you to take a livable artist fee!), and the language and tone of your proposal.

For example, how much more clear could ESP be?!

• Avoid interpretation of your work, and simply tell us what you plan to install.

• Avoid proposing materials that will not hold up in Eastern State’s environment. Work on paper or canvas, for example, generally cannot survive the harsh environment of Eastern State.

• Be careful not to romanticize the prison’s history, make unsupported assumptions about the lives of inmates or guards, or suggest sweeping generalizations. The prison’s history is complicated and broad. Simple statements often reduce its meaning.

• A proposal to work with prisoners or victims of violent crime by an artist who has never done so before, on the other hand, will raise likely concern.

• Do not suggest Eastern State solely as an architectural backdrop. Artist installations must deepen the experience of visitors who are touring this National Historic Landmark, addressing some aspect of the building’s significance.

• Many successful proposals, including Nick Cassway’s Portraits of Inmates in the Death Row Population Sentenced as Juveniles and Ilan Sandler’s Arrest, did not focus on Eastern State’s history at all. They did, however, address subjects central to the topic we hope our visitors will be contemplating during their visit.

• If you are going to include information about Eastern State’s history, please make sure you are accurate. Artists should be sensitive to the history of the space and only include historical information in the proposal if it is relevant to the work. Our staff is available to consult on historical accuracy.

• Overt political content can be good.

• The historic site staff has been focusing explicitly on the modern American phenomenon of mass incarceration, on questions of justice and effectiveness within the American prison system today, and on the effects of race and poverty on prison population demographics. We welcome proposals that can help engage our visitors with these complex subjects.

• When possible, the committee likes to see multiple viewpoints expressed among the artists who exhibit their work at Eastern State. Every year the committee reviews dozens of proposals for work that will express empathy for the men and women who served time at Eastern State. The committee has accepted many of these proposals, generally resulting in successful installations. These include Michael Grothusen’s midway of another day, Dayton Castleman’s The End of the Tunnel, and Judith Taylor’s My Glass House. The committee rarely sees proposals, however, that explore the impact of violence on families and society in general, or the perspective of victims of crime. Exceptions have been Ilan Sandler’s Arrest (2000 to 2003) and Sharyn O’Mara’s Victim Impact Statement (2010). We hope to see more installations on those themes in the future.

PAST GRANTEES

Check out the previous successful proposals and call ESP! Its staff are available to discuss the logistics of the proposal process and the history and significance of Eastern State Penitentiary.

DEADLINE: JUNE 17TH, 2015

Additional Resources

Sample Proposals

Past Installations

For more information contact Sean Kelley, Senior Vice President and Director of Public Programming, at sk@easternstate.org or telephone on (215) 236-5111, with extension #13.

After stints at Haverford College, PA; Scripps, CA; and Rutgers, NJ, my first solo-curated effort Prison Obscura is all grown up and headed to New York.

It’ll be showing at Parsons The New School of Design February 5th – April 17th:

Specifically, it’s at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center, located at 2 West 13th Street, New York, NY 10011.

On Thursday, February 5th at 5:45 p.m, I’ll be doing a curator’s talk. The opening reception follows 6:30–8:30 p.m. It’d be great to see you there.

Here’s the Parsons blurb:

The works in Prison Obscura vary from aerial views of prison complexes to intimate portraits of incarcerated individuals. Artist Josh Begley and musician Paul Rucker use imaging technology to depict the sheer size of the prison industrial complex, which houses 2.3 million Americans in more than 6000 prisons, jails and detention facilities at a cost of $70 billion per year; Steve Davis led workshops for incarcerated juvenile in Washington State to reveal their daily lives; Kristen S. Wilkins collaborates with female prisoners on portraits with the aim to compete against the mugshots used for both news and entertainment in mainstream media; Robert Gumpert presents a nine-year project pairing portraits and audio recordings of prisoners from San Francisco jails; Mark Strandquist uses imagery to provide a window into the histories, realities and desires of some incarcerated Americans; and Alyse Emdur illuminates moments of self-representations with collected portraits of prisoners and their families taken in prison visiting rooms as well as her own photographs of murals in situ on visiting room walls, and a mural by members of the Restorative Justice and Mural Arts Programs at the State Correctional Institution in Graterford, PA. Also, included are images presented as evidence during the landmark Brown v. Plata case, a class action lawsuit that which went all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States, where it was ruled that every prisoner in the California State prison system was suffering cruel and unusual punishment due to overcrowded facilities and the failure by the state to provide adequate physical and mental healthcare.

Parsons has scheduled a grip of programming while the show is on the walls:

Mid-day discussion with curator Pete Brook and Tim Raphael, Director, The Center for Migration and the Global City, Rutgers University-Newark.

Wednesday, February 4, 12:00–1:30 p.m.

Co-hosted with the Humanities Action Lab.

These Images Won’t Tell You What You Want: Collaborative Photography and Social Justice.

Friday, February 27, 6:00 p.m.

A talk by Mark Strandquist.

Windows from Prison

Saturday, February 28

A workshop led by Mark Strandquist. More information about participation will be available on the website.

Visualizing Carceral Space

Thursday, March 12, 6:00 p.m.

A talk by Josh Begley.

Please spread the word. Here’s a bunch of images for your use.

PARTNERS

At The New School, Prison Obscura connects to Humanities Action Lab (HAL) Global Dialogues on Incarceration, an interdisciplinary hub that brings together a range of university-wide, national, and global partnerships to foster public engagement on America’s prison system.

Prison Obscura is a traveling exhibition made possible with the support of the John B. Hurford ‘60 Center for the Arts and Humanities and Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College, Haverford, PA.

Sébastien van Malleghem has been awarded the 2015 Lucas Dolega Award for Prisons his four years (2011-2014) of reportage from within the Belgian prison system.

I’m a big fan of the work having previously interviewed Sébastien while the work was ongoing and applauded the time he spent three-days locked up in Belgium’s newest most high tech prison. That experience helped van Malleghem understand that there are some very thin but very significant thread that connect the cameras and lenses of security, with the cameras and lenses of photographers and journalists, with the cameras of news and entertainment.

In his formal statement to the Lucas Dolega Award, van Malleghem says:

These images reveal the toll taken by a societal model [the prison] which brings out tension and aggressiveness, and amplifies failure, excess and insanity, faith and passion, poverty.

These images expose how difficult it is to handle that which steps out of line. This, in a time when that line is more and more defined by the touched-up colors of standardization, of the web and of reality TV.

Always further from life, from our life, [prisoners] locked up in the idyllic, yet confined, space of our TV and computer screens.

In an interview with Molly Benn, Sébastien (mashed through Google translate) says a couple of valid things. They answer key questions young photographers have, firstly about access, and secondly about behaviour in the prison.

No one will tell you up front “You should contact so-and-so.” I went to see the mayor of Nivelles. I forwarded to the director of the prison in Nivelles, who referred me to a government worker. Those exchanges took 8-months. Every time I was asked to re-explain my project. Eventually, I received written permission by email but, still, each warden could still refuse me if he wished.

and

In prison, everything is constantly monitored. My first challenge was to get out from under the constant control. Upon entry into prison, you are immediately assigned an agent, supposedly for your safety but mostly to monitor what you’re doing.

But the prison officer ranks are often understaffed. I quickly noticed that they preferred to work their usual job than be my baby-sitter. So. I asked questions, showed interest in their profession, and I gained their confidence. After this, they let me work quite freely.

Basically, photographing in prison is a precarious exercise. I recall the words of one photographer who reflected on this best when he told me he never presumed he’d be let back in the next day or next week. He made images as if that day in the prison was his last.

Van Malleghem’s prison work follows on from years documenting Belgian police.

LUCAS DOLEGA AWARD

Lucas von Zabiensky Mebrouk Dolega grew up between Germany – his mother’s homeland, Morocco – his father’s – and France. Never one to respect authority for authority’s sake, he needled the inconcstencies and the inbetween spaces of persons’ experience and identity. On January 17th 2011, in Tunis, Lucas died on the streets amid a riot. He was covering the “Jasmin Revolution” in Tunisia.

The Lucas Dolega Award honours Dolega’s spirit and contribution. The award recognises freelance photographers who take risks in the pursuit of infomration and informing the world. Previous recipients are Emilio Morenatti (2012), Alessio Romenzi (2013) and Majid Saeedi (2014).