You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Eastern State Penitentiary’ tag.

The Big Graph (2014). Photo: Courtesy Eastern State Penitentiary.

Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site Guidelines for Art Proposals, 2016

Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia has announced some big grants for artists working to illuminate issues surrounding American mass incarceration.

READ! FULL INFO HERE

ESP is offering grants of $7,500 for a “Standard Project” and a grant of $15,000 for specialized “Prisons in the Age of Mass Incarceration Project.” In each case the chosen installations shall be in situ for one full tour season — typically May 1 – November 30 (2016).

DEADLINE: JUNE 17TH

THE NEED

ESP has, in my opinion, the best programming of any historic prison site when it comes to addressing current prison issues. Last year, they installed The Big Graph (above) so that the monumental incarceration rates could tower over visitors. Now, ESP wants to explore the emotional aspects of those same huge figures.

“Prisons in the Age of Mass Incarceration will serve as a counterpoint to The Big Graph,” says ESP. “Where The Big Graph addresses statistics and changing priorities over time, Prison in the Age will encourage reflection on the impact of recent changes to the American criminal justice system, and create a place for visitors to reflect on their personal experiences and share their thoughts with others.”

ESP says that art has “brought perspectives and approaches that would not have been possible in traditional historic site programming.” Hence, these big grant announcements And hence these big questions.

“Who goes to prison? Who gets away with it? Why? Have you gotten away with something illegal? How might your appearance, background, family connections or social status have affected your interaction with the criminal justice system? What are prisons for? Do prisons “work?” What would a successful criminal justice system look like? What are the biggest challenges facing the U.S criminal justice system today? How can visitors affect change in their communities? How can they influence evolving criminal justice policies?” asks ESP.

While no proposal must address any one or all of these questions specifically they delineate the political territory in which ESP is interested.

“If our definition of this program seems broad, it’s because we’re open to approaches that we haven’t yet imagined,” says ESP. “We want our visitors to be challenged with provocative questions, and we’re prepared to face some provocative questions ourselves. In short, we seek memorable, thought-provoking additions to our public programming, combined with true excellence in artistic practice.”

“We seek installations that will make connections between the complex history of this building and today’s criminal justice system and corrections policies,” continues ESP. “We want to humanize these difficult subjects with personal stories and distinct points of view. We want to hear new voices—voices that might emphasize the political, or humorous, or bluntly personal.”

GO TO AN ORIENTATION

ESP won’t automatically exclude you, but you seriously hamper your chances if you don’t attend one of the artist orientation tours.

They occur on March 15, April 8, April 10, April 12, May 1, May 9, May 15, June 6.

Also, be keen to read very carefully the huge document detailing the grants. It explains very well what ESP is looking for including eligibility, installation specifics, conditions on site, maintenance, breakdown of funding (ESP instructs you to take a livable artist fee!), and the language and tone of your proposal.

For example, how much more clear could ESP be?!

• Avoid interpretation of your work, and simply tell us what you plan to install.

• Avoid proposing materials that will not hold up in Eastern State’s environment. Work on paper or canvas, for example, generally cannot survive the harsh environment of Eastern State.

• Be careful not to romanticize the prison’s history, make unsupported assumptions about the lives of inmates or guards, or suggest sweeping generalizations. The prison’s history is complicated and broad. Simple statements often reduce its meaning.

• A proposal to work with prisoners or victims of violent crime by an artist who has never done so before, on the other hand, will raise likely concern.

• Do not suggest Eastern State solely as an architectural backdrop. Artist installations must deepen the experience of visitors who are touring this National Historic Landmark, addressing some aspect of the building’s significance.

• Many successful proposals, including Nick Cassway’s Portraits of Inmates in the Death Row Population Sentenced as Juveniles and Ilan Sandler’s Arrest, did not focus on Eastern State’s history at all. They did, however, address subjects central to the topic we hope our visitors will be contemplating during their visit.

• If you are going to include information about Eastern State’s history, please make sure you are accurate. Artists should be sensitive to the history of the space and only include historical information in the proposal if it is relevant to the work. Our staff is available to consult on historical accuracy.

• Overt political content can be good.

• The historic site staff has been focusing explicitly on the modern American phenomenon of mass incarceration, on questions of justice and effectiveness within the American prison system today, and on the effects of race and poverty on prison population demographics. We welcome proposals that can help engage our visitors with these complex subjects.

• When possible, the committee likes to see multiple viewpoints expressed among the artists who exhibit their work at Eastern State. Every year the committee reviews dozens of proposals for work that will express empathy for the men and women who served time at Eastern State. The committee has accepted many of these proposals, generally resulting in successful installations. These include Michael Grothusen’s midway of another day, Dayton Castleman’s The End of the Tunnel, and Judith Taylor’s My Glass House. The committee rarely sees proposals, however, that explore the impact of violence on families and society in general, or the perspective of victims of crime. Exceptions have been Ilan Sandler’s Arrest (2000 to 2003) and Sharyn O’Mara’s Victim Impact Statement (2010). We hope to see more installations on those themes in the future.

PAST GRANTEES

Check out the previous successful proposals and call ESP! Its staff are available to discuss the logistics of the proposal process and the history and significance of Eastern State Penitentiary.

DEADLINE: JUNE 17TH, 2015

Additional Resources

Sample Proposals

Past Installations

For more information contact Sean Kelley, Senior Vice President and Director of Public Programming, at sk@easternstate.org or telephone on (215) 236-5111, with extension #13.

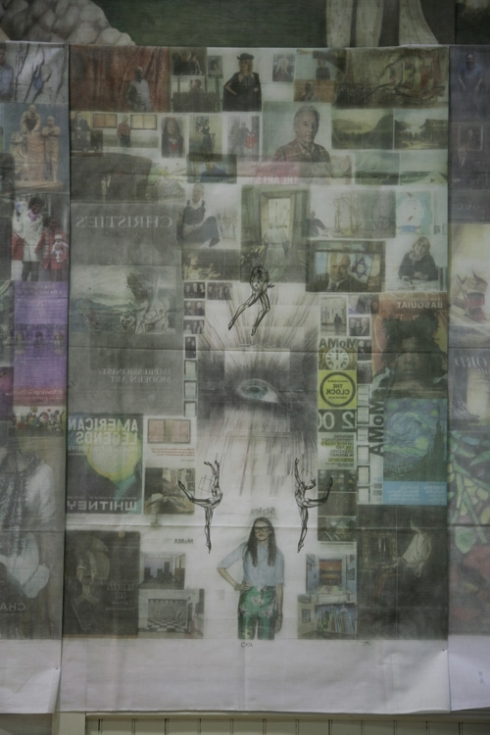

Artist Jesse Krimes stands in front of his 39-panel mural Apokaluptein:16389067 (federal prison bed sheets, transferred New York Times images, color pencil) installed, here, at the Olivet Church Artist Studios, Philadelphia. January, 2014.

The New York Times has a track record for high quality visual journalism. From experiments in multimedia, to its magazine’s double-truck features; from its backstage reportage at the swankiest fashion gigs, to their man in town Bill Cunningham. Big reputation.

NYT photographs are viewed and used in an myriad of ways. Even so, I doubt the editors ever thought their choices would be burnished from the news-pages onto prison bed-sheets with a plastic spoon. Nor that the transfer agent would be prison-issue hair gel.

In 2009, Jesse Krimes (yep, that’s his real surname) was sentenced to 70 months in a federal penitentiary for cocaine possession and intent to distribute. He was caught with 140 grams. The charges brought were those of 50-150 kilos. Somewhere in the bargaining it was knocked down to 500 grams, and Krimes plead guilty to conspiracy. The judge recommended that Jesse be sent to a minimum security prison in New Jersey, close to support network of friends and family, but the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) opted to send him to a medium security facility in Butner, North Carolina — as far away as permitted under BOP regulations. That was the first punitive step of many in a system that Krimes says is meant first and foremost to dehumanise.

“Doing this was a way to fight back,” says Krimes who believes ardently that art humanises. “The system is designed to make you into a criminal and make you conform. I beat the system.”

Last month, I had the pleasure of hearing Krimes speak about his mammoth artwork Apokaluptein:16389067 during an evening hosted at the the Eastern State Penitentiary and Olivet Church Artist Studios in Philadelphia.

The mural took three years to make and it is a meditation on heaven, hell, sin, redemption, celebrity worship, deprivation and the nature of perceived reality. Krimes says his “entire experience” of prison is tied up in the artwork.

In the top-left is a transferred photo of a rehearsal of the Passion play at Angola Prison, Louisiana.

Through trial and error, Krimes discovered that he could transfer images from New York Times newspapers on to prison bedsheets. At first he used water, but the colours bled. Hair gel had the requisite viscosity. As a result, all imagery is reversed, upturned. Apokaluptein:16389067 is both destruction and creation.

“It’s a depiction of represented reality as it exists in its mediated form, within the fabric of the prison,” says Krimes. “It was my attempt to transfer [outside] reality into prison and then later became my escape when I sent a piece home with the hopes that it could be my voice on the outside in the event that anything bad ever happened and I never made it home.”

ART AS SURVIVAL

Krimes says this long term project kept him sane, focused and disciplined.

Each transfer took 30-minutes. Thousands make up the mural. Krimes only worked on one sheet at a time, each of them matching the size of the tabletop he worked on. A notch in the table marked the horizon line for the 13 panels making up the center horizontal. He shipped them home. Not until his release did he see them together.

The enterprise was not without its risks, but Krimes found favour being a man with artistic talent. He established art classes for fellow prisoners in an institution that was devoid of meaningful programs.

“Prisoners did all the work to set up the class,” says Krimes.

Once the class was in place, guards appreciated the initiative. It even changed for the better some of the relationships he had with staff.

“Some helped mail out sections,” he says of the bedsheets which were, strictly-speaking, contraband.

Krimes would cut sections from the New York Times and its supplements, sometimes paying other prisoners for the privilege.

“In prison, the only experience of the outside world is through the media.”

The horizon is made of images from the travel section. Beneath the horizon are transferred images of war, and man-made and natural disasters. Krimes noticed that often coverage of disasters and idealised travel destinations came from the same coasts and continents. Influenced by Dante’s Inferno and by Giorgio Agamben’s The Kingdom and the Glory, Krimes reinvigorates notions of the Trinity within modern politics and economics. The three tiers of the mural reflect, he says heaven, earth and hell, or intellect, mind and body.

One can identify the largest victories, struggles and crimes of the contemporary world. All in perverse reverse. All in washed out collage. There’s images of the passion play being rehearsed at Angola Prison from an NYT feature, of Tahrir Square and the Egyptian revolution, of children in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook School massacre, and of a submerged rollercoaster in the wake of Hurricane Sandy.

The women’s rights panel includes news images from reporting on the India bus rape and images of Aesha Mohammadzai who was the victim of a brutal attack by her then husband who cut off her nose. Krimes’ compression of images is vertiginous and disorienting. We’re reminded that the world as it appears through our newspapers sometimes is.

The large pictures are almost exclusively J.Crew adverts which often fill the entire rear page of the NYT. Jenna Lyons, the creative director at J.Crew is cast as a non-too-playful devil imp in the center-bottom panel.

Throughout, fairies transferred straight from ballerinas bodies as depicted in the Arts Section dance and weave. Depending on where they exist in relation to heaven and earth they are afforded heads or not — blank geometries replace faces as to comment on the treatment of women in mainstream media.

The title Apokaluptein:16389067 derives from the Greek root ‘apokalupsis.’ Apokaluptein means to uncover, or reveal. 16389067 was Krimes’ Federal Bureau of Prisons identification number.

“The origin [of the word] speaks to the material choice of the prison sheet as the skin of the prison, that is literally used to cover and hide the body of the prisoner. Apokaluptein:16389067 reverses the sheet’s use and opens up the ability to have a conversation about the sheet as a material which, here, serves to uncover and reveal the prison system,” says Krimes who also read into the word personal meaning.

“The contemporary translation speaks to a type of personal apocalypse — the process of incarceration and the dehumanizing deterioration of ones personal identity, […] The number itself, representing the replacement of ones name.”

PRISON ECONOMICS: THE HAVES & HAVE NOTS

One of the most interesting things to hear about at Krimes’ presentation was the particular details about how he went about acquiring materials. In federal prison, just as on the outside, money rules. Except inside BOP facilities the currency is stamps not dollars (something we’ve heard before). A $7 book of stamps on the outside, sets a prisoner back $9.

Access to money makes a huge difference in how one experiences imprisonment.

“People who have money have a much easier time living in prison but that is usually rare except for the white collar guys or the large organized crime figures,” says Krimes.

“Prisoners who have money in prison gain automatic respect and power because you are able to have influence over anything really — most people without money will depend on those with cash to be the buyers of whatever products or services they need.”

Without cash to hand, a rare skill comes in handy. Krimes could make art. In prison artists are afforded much respect. Ironically, free society doesn’t treat artists with the same respect, but I guess we’ve already established that we’re dealing in reversals here?!

“We had to provide some kind of skill or service in order to receive money or books of stamps. Some people cook for others, do laundry, do legal work, or artwork.”

In FCI Butner, a high-quality photorealistic portrait would go for as much as $150. Or, 20 books of stamps. Krimes did portraits and tattoo designs, spending proceeds almost exclusively on hair gel and coloured pencils.

“The majority of portraits I did were for the guys who had money or else I did them for free, for friends or those going through hard times.”

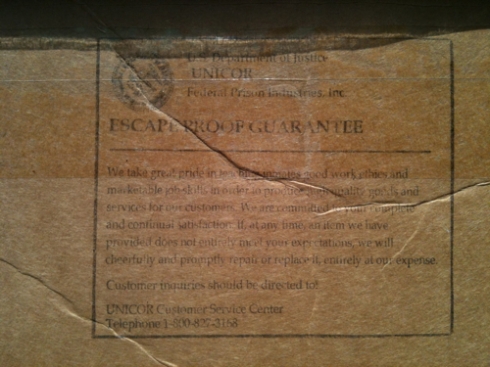

The prison sheets came for free. Krimes smiles at the irony that these sheets are made by UNICOR, the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ factory and industries arm. UNICOR makes everything from steel frame beds to bedsheets; from U.S. military boots and helmets to plastic utensils. In 2005, UNICOR generated $765 million in sales — 74% of revenues went toward the purchase of raw material and equipment; 20% toward staff salaries; and 6% went toward inmate salaries.

I’d liken Krimes’ acquisition of bed sheets to liberation more than to theft. His image transfers are appropriation more than homage. The scope of the project reflects the sheer size of American prison system. The ambition reflects that of the individual to survive, not the system to improve its wards.

That such a large statement came out of the prison sytem (in one piece!) is a feat in itself. That Apokaluptein:16389067 is so layered and so plugged into contemporary culture is an absolute marvel. That the photographs of international media are the vehicle for that statement should be no surprise at all.

More here.

All images: Sarah Kaufman

One of the cardboard boxes in which Krimes shipped out a completed panel. The boxes are made by the federal prison industries group UNICOR which employs prison labour. The box is marked with “ESCAPE PROOF GUARANTEED.”

“I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body”

– Charles Dickens, American Notes, (Harper & Brothers, 1842) p. 39

If we are to understand how and why prisons function in modern America, it is helpful to know their history. As many of you will be aware there was a time in Western societies when prisons were not the primary form of punishment; instead jails were used for short sentences for disturbing the peace, debt, being poor and as a means to hold people before trial.

Likewise, prisons have not always used solitary confinement. Solitary today is used to punish (sometimes minor) infractions within a prison or to isolate inmates during an investigation/following an incident. Its use differs institution to institution.

Needless to say, on any given day in America 20,000 people are held in solitary despite scientific proof it damages the psyche and regresses basic functioning.

With that in mind, the origins of the practice are pause for thought. In the above video, Sean Kelley, Program Director at Eastern State Penitentiary outlines the history of the famed prison in Philadelphia, and its evolution of the practice of solitary confinement.

PRODUCTION

‘The Invention of Solitary‘ was produced by Muralla Media Works headed up by Chris Bravo and Lindsey Schneider.

Bravo and Schneider are involved in several projects and as such I’d describe them both as media activists. They’ve produced advocacy video for incarcerated women and for the mentally ill in prisons. They were also videographers at the ‘Fighting Prisons’ panels at the 2010 US Social Forum.

Their largest current project is CONTROL, a feature-length documentary that tells the story of youth whose lives have been caught in the web of the criminal justice system. View the trailer.

With audio-visuals as their material, it is interesting that they also muse – through the SILENCE OPENS DOORS webzine on the history and philosophy of silence & noise.

Which brings us full circle – read the SILENCE OPENS DOORS blog post about The Invention of Solitary.