You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Butner’ tag.

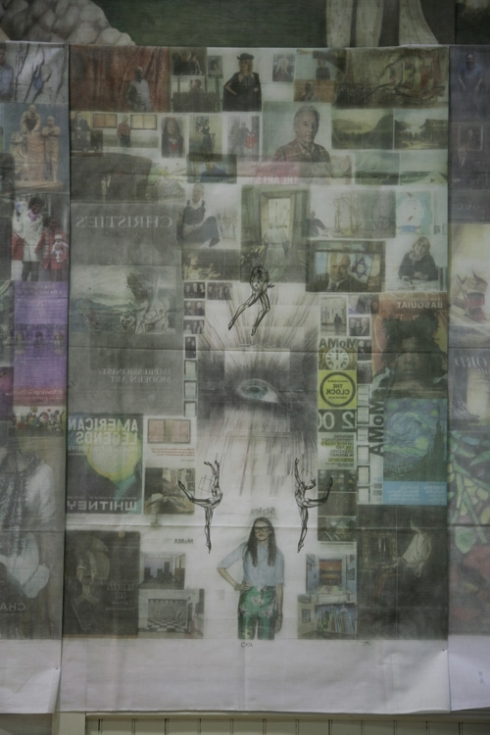

Artist Jesse Krimes stands in front of his 39-panel mural Apokaluptein:16389067 (federal prison bed sheets, transferred New York Times images, color pencil) installed, here, at the Olivet Church Artist Studios, Philadelphia. January, 2014.

The New York Times has a track record for high quality visual journalism. From experiments in multimedia, to its magazine’s double-truck features; from its backstage reportage at the swankiest fashion gigs, to their man in town Bill Cunningham. Big reputation.

NYT photographs are viewed and used in an myriad of ways. Even so, I doubt the editors ever thought their choices would be burnished from the news-pages onto prison bed-sheets with a plastic spoon. Nor that the transfer agent would be prison-issue hair gel.

In 2009, Jesse Krimes (yep, that’s his real surname) was sentenced to 70 months in a federal penitentiary for cocaine possession and intent to distribute. He was caught with 140 grams. The charges brought were those of 50-150 kilos. Somewhere in the bargaining it was knocked down to 500 grams, and Krimes plead guilty to conspiracy. The judge recommended that Jesse be sent to a minimum security prison in New Jersey, close to support network of friends and family, but the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) opted to send him to a medium security facility in Butner, North Carolina — as far away as permitted under BOP regulations. That was the first punitive step of many in a system that Krimes says is meant first and foremost to dehumanise.

“Doing this was a way to fight back,” says Krimes who believes ardently that art humanises. “The system is designed to make you into a criminal and make you conform. I beat the system.”

Last month, I had the pleasure of hearing Krimes speak about his mammoth artwork Apokaluptein:16389067 during an evening hosted at the the Eastern State Penitentiary and Olivet Church Artist Studios in Philadelphia.

The mural took three years to make and it is a meditation on heaven, hell, sin, redemption, celebrity worship, deprivation and the nature of perceived reality. Krimes says his “entire experience” of prison is tied up in the artwork.

In the top-left is a transferred photo of a rehearsal of the Passion play at Angola Prison, Louisiana.

Through trial and error, Krimes discovered that he could transfer images from New York Times newspapers on to prison bedsheets. At first he used water, but the colours bled. Hair gel had the requisite viscosity. As a result, all imagery is reversed, upturned. Apokaluptein:16389067 is both destruction and creation.

“It’s a depiction of represented reality as it exists in its mediated form, within the fabric of the prison,” says Krimes. “It was my attempt to transfer [outside] reality into prison and then later became my escape when I sent a piece home with the hopes that it could be my voice on the outside in the event that anything bad ever happened and I never made it home.”

ART AS SURVIVAL

Krimes says this long term project kept him sane, focused and disciplined.

Each transfer took 30-minutes. Thousands make up the mural. Krimes only worked on one sheet at a time, each of them matching the size of the tabletop he worked on. A notch in the table marked the horizon line for the 13 panels making up the center horizontal. He shipped them home. Not until his release did he see them together.

The enterprise was not without its risks, but Krimes found favour being a man with artistic talent. He established art classes for fellow prisoners in an institution that was devoid of meaningful programs.

“Prisoners did all the work to set up the class,” says Krimes.

Once the class was in place, guards appreciated the initiative. It even changed for the better some of the relationships he had with staff.

“Some helped mail out sections,” he says of the bedsheets which were, strictly-speaking, contraband.

Krimes would cut sections from the New York Times and its supplements, sometimes paying other prisoners for the privilege.

“In prison, the only experience of the outside world is through the media.”

The horizon is made of images from the travel section. Beneath the horizon are transferred images of war, and man-made and natural disasters. Krimes noticed that often coverage of disasters and idealised travel destinations came from the same coasts and continents. Influenced by Dante’s Inferno and by Giorgio Agamben’s The Kingdom and the Glory, Krimes reinvigorates notions of the Trinity within modern politics and economics. The three tiers of the mural reflect, he says heaven, earth and hell, or intellect, mind and body.

One can identify the largest victories, struggles and crimes of the contemporary world. All in perverse reverse. All in washed out collage. There’s images of the passion play being rehearsed at Angola Prison from an NYT feature, of Tahrir Square and the Egyptian revolution, of children in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook School massacre, and of a submerged rollercoaster in the wake of Hurricane Sandy.

The women’s rights panel includes news images from reporting on the India bus rape and images of Aesha Mohammadzai who was the victim of a brutal attack by her then husband who cut off her nose. Krimes’ compression of images is vertiginous and disorienting. We’re reminded that the world as it appears through our newspapers sometimes is.

The large pictures are almost exclusively J.Crew adverts which often fill the entire rear page of the NYT. Jenna Lyons, the creative director at J.Crew is cast as a non-too-playful devil imp in the center-bottom panel.

Throughout, fairies transferred straight from ballerinas bodies as depicted in the Arts Section dance and weave. Depending on where they exist in relation to heaven and earth they are afforded heads or not — blank geometries replace faces as to comment on the treatment of women in mainstream media.

The title Apokaluptein:16389067 derives from the Greek root ‘apokalupsis.’ Apokaluptein means to uncover, or reveal. 16389067 was Krimes’ Federal Bureau of Prisons identification number.

“The origin [of the word] speaks to the material choice of the prison sheet as the skin of the prison, that is literally used to cover and hide the body of the prisoner. Apokaluptein:16389067 reverses the sheet’s use and opens up the ability to have a conversation about the sheet as a material which, here, serves to uncover and reveal the prison system,” says Krimes who also read into the word personal meaning.

“The contemporary translation speaks to a type of personal apocalypse — the process of incarceration and the dehumanizing deterioration of ones personal identity, […] The number itself, representing the replacement of ones name.”

PRISON ECONOMICS: THE HAVES & HAVE NOTS

One of the most interesting things to hear about at Krimes’ presentation was the particular details about how he went about acquiring materials. In federal prison, just as on the outside, money rules. Except inside BOP facilities the currency is stamps not dollars (something we’ve heard before). A $7 book of stamps on the outside, sets a prisoner back $9.

Access to money makes a huge difference in how one experiences imprisonment.

“People who have money have a much easier time living in prison but that is usually rare except for the white collar guys or the large organized crime figures,” says Krimes.

“Prisoners who have money in prison gain automatic respect and power because you are able to have influence over anything really — most people without money will depend on those with cash to be the buyers of whatever products or services they need.”

Without cash to hand, a rare skill comes in handy. Krimes could make art. In prison artists are afforded much respect. Ironically, free society doesn’t treat artists with the same respect, but I guess we’ve already established that we’re dealing in reversals here?!

“We had to provide some kind of skill or service in order to receive money or books of stamps. Some people cook for others, do laundry, do legal work, or artwork.”

In FCI Butner, a high-quality photorealistic portrait would go for as much as $150. Or, 20 books of stamps. Krimes did portraits and tattoo designs, spending proceeds almost exclusively on hair gel and coloured pencils.

“The majority of portraits I did were for the guys who had money or else I did them for free, for friends or those going through hard times.”

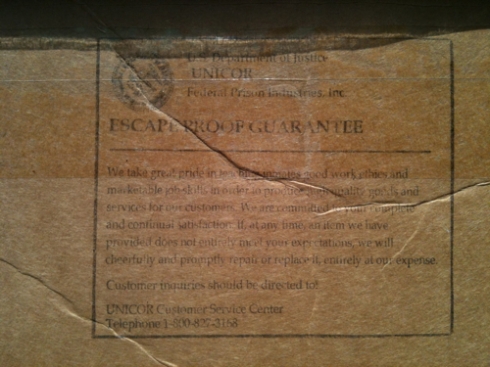

The prison sheets came for free. Krimes smiles at the irony that these sheets are made by UNICOR, the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ factory and industries arm. UNICOR makes everything from steel frame beds to bedsheets; from U.S. military boots and helmets to plastic utensils. In 2005, UNICOR generated $765 million in sales — 74% of revenues went toward the purchase of raw material and equipment; 20% toward staff salaries; and 6% went toward inmate salaries.

I’d liken Krimes’ acquisition of bed sheets to liberation more than to theft. His image transfers are appropriation more than homage. The scope of the project reflects the sheer size of American prison system. The ambition reflects that of the individual to survive, not the system to improve its wards.

That such a large statement came out of the prison sytem (in one piece!) is a feat in itself. That Apokaluptein:16389067 is so layered and so plugged into contemporary culture is an absolute marvel. That the photographs of international media are the vehicle for that statement should be no surprise at all.

More here.

All images: Sarah Kaufman

One of the cardboard boxes in which Krimes shipped out a completed panel. The boxes are made by the federal prison industries group UNICOR which employs prison labour. The box is marked with “ESCAPE PROOF GUARANTEED.”

David Simonton contacted me and shared his long term project at the former Polk Youth Center in Raleigh. After thoughtful discussions David and I decided upon a pairing of articles.

In this post, Part One, David talks about the background to the project and his objectives in the work.

I also chose a selection of David’s prints to showcase and offer comment. At the bottom is a thumbnail-pop-out-gallery with all the pictures in one place.

…and, in a few weeks, Part Two will dissect the atypically rich and varied visual-history of the Polk Youth Center.

David Simonton’s Commentary (PP’s Subheaders)

Photographing Disused Architectures of Citizen Management

In the late-1980’s I was one of a number of photographers working on Ellis Island, the former Immigration Station in New York Harbor, documenting the progress of the restoration of the facility (reopened to the public in 1990).

The project was called “The Ellis Island Project: Documentation/Interpretation.” I was living in New Jersey at the time, and traveled to the island to photograph twice a week for nine months. During this period I was also pursuing my personal projects.

Opportunist Photographer

In 1989, I moved to North Carolina

The “Old” Polk Youth Center/Prison, Raleigh which has a long and storied history, closed in 1997 when a modern facility (which the “Old Polk,” most assuredly, was NOT) opened in Butner, NC. The inmates were transferred to Butner in November of that same year.

Living nearby, I could hardly resist the opportunity to photograph there. So before any “No Trespassing” signs were posted, I went and photographed the site. The doors (cell doors, some of them) to many of the buildings were wide open!

“Old” Polk Youth Center – a euphemism if ever there was one – was located on land directly adjacent to the North Carolina Museum of Art in West Raleigh, near the State Fairgrounds.

The prison buildings were razed in 2003. But before that occurred, the prison was essentially abandoned until the land (along with the buildings on it) was transferred to the museum.

Official Photographer

During the mid-nineties, I exhibited my personal, interpretive work from Ellis Island – 90 images – at a gallery in Raleigh. Huston Paschal, a curator at the state art museum, attended the exhibition.

Unaware that I had already photographed there, Huston Paschal invited me to document the site, which was now in the museum’s hands. In late-2000 the invitation was formalized with a commission. I continued working on the project (even after the commission had lapsed) until the buildings came down, the ground leveled and grass planted.

My involvement was always with an empty site, when the prison was closed and inmates transferred. I photographed a long-abandoned facility: empty buildings, empty cellblocks and overgrown grounds.

Simonton: “Art for art’s sake”

As an art photographer (an unfortunate, nearly pretentious-sounding term, even if it’s the category my work falls into), my goal is to make interesting pictures; interesting in-and-of themselves, so that THEY are worth looking at, repeatedly.

What’s depicted is not unimportant, but it’s of secondary importance; this is my approach to my own picture making. The fact that my “subject” was a prison is happenstance – I photograph all kinds of abandoned structures. I also photograph the smalls town North Carolina (day and night) and photograph landscapes. An interesting photograph is always my intent, even when what it depicts is not itself inherently interesting … or beautiful.

Art and Documentary converge.

The Polk project was a “documentary” project, but not in the strict sense of it being wholly objective. My pictures describe the place I saw, and, if not the place I “saw”, then the place I thought and felt.

The project is not a comprehensive cataloging of the site either; rather, the pictures reflect my response to it during the passage of several years. They inform history by showing the place as it was in those waning years, after being – at long last – set aside as a relic; finally to be torn down and planted over and – with still more time – forgotten.

Polk Youth Center was located in a heavily populated area, which was not the case when it was built. Improvements were rarely made because, why spend money on any improvements if the facility was about to be moved or closed? – as were the recurrent promises for decades.

Institutional Narratives

I was not aware of the prison or the prison sites history until after I had completed my work; which may be just as well, since it was difficult enough to find beauty in such a physically “unbeautiful” place.

Had I been mindful of the ugly history of the old Polk Youth Center – riots, rape and other forms of violence in its final years, – I may have had a harder time photographing.

Prison Photography’s Commentary

Simonton’s three years at Polk yielded a varied portfolio. In editing the selection (from 100+ images to these 16) images distinguished themselves for very different reasons. If the lens wasn’t pointed at something crumbling, it was pointing at something overgrown and grown over.

Some images (Steep Steps) are flattened and exposed matter-of-factly, whereas others (Laundry Bin) luxuriate in silvery sheen.

I choose one pairing here of the same view in different season; Simonton took many pairings so to secure the evidence of time in his series. Apparently, the chimney was a signature of Raleigh’s landscape.

It is in the different states of dilapidation that one finds a visual allusions. Simonton’s photograph of the teeth counterpoise the dental ephemera in Edmund Clark’s photography of a functioning geriatric UK prison wing. When given the opportunity, Simonton ties the fragility of the body to the decay of the site.

Other recalls. Simonton’s cavernous grimed up cells, the expired bird, the textural friction between hard concrete and friable life are not too dissimilar to Roger Ballen. The reflected dormitory of cacophonous bed frames is a Moholy-Nagy-informed dark-fantasia march of welded steel.

Only a few of Simonton’s images describe the site as one of incarceration. Few of the normal visual clues are available; no visible bars on windows, no holding cages. This could as easily be a disused YMCA or summer camp.

For Prison Photography, the real interest in Simonton’s work comes when it is positioned in a wider context of the site. David provided me with background info and some press clippings which whetted my appetite. Further research was rewarded with an unusual series of photographic manoeuvers sequentially on this site through its various guises. All of this I will cover in Part Two.

Closure & Erasure

The photo of the evacuation plan below touches upon that procedural rigour that has cycled at the site of the former Youth Polk Center. The image at the very bottom (as well as being Simonton’s favourite) is a fine accompaniment to the evacuation plan.

Both images bear evidence of water blistering, bubbling and staining its way through materials. These evocations are “Art for Art’s sake” but they are also poetic closures, historical records and proof that in the absence of human interference erasure sets in rapidly.

David Simonton has been a photographer for 40 years and has been photographing North Carolina for the past 20 years. An adjunct instructor of photography at Peace College in Raleigh, David often chooses to focus on the more rural parts of the state. His series “Photographs from North Carolina” features black-and-white photographs from the 345 North Carolina towns he has visited. He has completed commissions for the North Carolina Museum of Art and the United Arts Council of Raleigh and Wake County. He has had work in solo and group exhibitions throughout the United States, and his photographs are in the permanent collection of the North Carolina Museum of Art. David was awarded a visual artist fellowship from the North Carolina Arts Council in 2001. (via)

View other images at David Simonton’s website. Indyweek have written on his work previously.

Thank you to David Simonton for reaching out. Thanks for the time spent over questions and for your collaboration. Pleasure working with you.