Cameras needn’t always be a security tool. And, in the hands of prisoners, they needn’t be a security hazard. I’m always encouraged to find photo-education-projects in prisons that nurture storytelling skills of prisoners. Therefore, the Inside View project in Guernsey, a Channel Island in Europe, is cause for interrogation.

CONTEXT

I’ve written about the history of photography workshops in prisons, but let me offer a quick re-cap. Except for photo workshops in New York in the 1970s to Washington D.C. in the 1980s no other photography classes that I know of have existed in male adult prisoners in the U.S. None occur today.

Internationally, programs in Columbia, Romania and Switzerland prove the model exists. In U.S. juvenile facilities photo education has operated in Washington State and currently exists in New Mexico and Rhode Island. Generally, we can say that these isolated examples are the exception rather than the rule.

A SIGNIFICANT PROGRAM

Given the paucity of photo-workshops, current and ongoing programs such Inside View are noteworthy, and Inside View might even be a program from which we can learn. It could be replicated! Inside View is the brain child of Jean-Christophe Godet, who also happens to be the Director of the Guernsey Photography Festival.

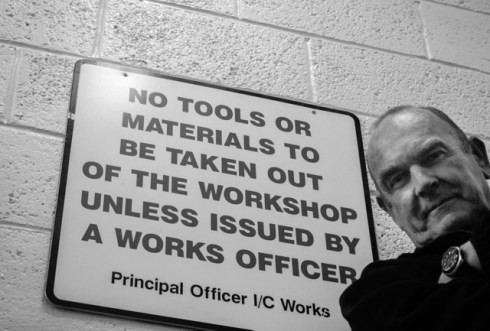

“Designed to help the participants acquire new technical and social skills, a sense of responsibility, a better understanding of themselves and a greater awareness of the environment in which they live in,” reads the press release, the Inside View project gives prisoners access to equipment and teaches them technical skills.

Inside View started at the end of 2010 with workshops taking place each week over six months. To date, three workshops have taken place, always discussing the importance of objectivity and integrity in creating a documentary.

“The thing I can’t get my head round is that these teachers trust us,” says one prisoner-participant in the same press release. “They respect us and give us well expensive kit to hold and to use. The cameras belong to them and it feels good to be given the responsibility to be trusted with their precious cameras. I will always have the camera round my neck, I will teach my children to look after their things and to respect kit”

“I like it when this gives us a chance to show the outside that we don’t live in a 5* hotel,” reflect a another participant. “We are told when to eat, when to exercise, and we see doors but cant open them. I think that our pictures have captured the essence of what it is to lose your freedom. That’s why our photos are so good”

The assistance of the Governor and prison officers was essential for Inside View to play out, with Officers Dave White and Belinda Help at the sharp end of negotiating the exemplary project.

David Matthews, Guernsey Prisons Governor says, “It is important that prisoners can learn technical and life skills whilst in custody, these new skills can help in reducing offending behaviour and aid resettlement. There is a marked difference in behaviour and attitude when prisoners are exposed to these types of activities.”

LESSONS LEARNT

Let’s be clear, the Channel Island of Guernsey is quite different to the U.S., or anywhere else for that matter. It is a province with a population of only 65,000. It has a single prison — The Guernsey Prison — with only 122 prisoners. For the sake of comparison, that’s 0.005% of the U.S. prison population which stands at 2.3 million.

If we wanted to imagine a similar program taking grip in the American prison industrial complex, we’d have to deal with massive issues of scale and the inconveniences they cause. Nevertheless, the point is made, photography can be a voice for prisoners — to facilitate that there only need be the resources, the will of any given administration, and systems of political and security that are less interested in covering their ass than they are in delivering rehabilitation.

To find out exactly how the program came about, I asked Inside View coordinator Jean-Christophe Godet a few questions.

Prison Photography (PP): Where did the idea to put cameras in the hands of prisoners come from?

JCG: Inside View was inspired by a similar project organised by a collective of photographers “FrameZero” at the Wandsworth Prison in London in the late 90’s. The project was run by Jason Shenaï.

PP: You worked with the Guernsey prison services. How did you negotiate that?

JCG: It took almost three very long years of negotiation. My first letters and emails were simply ignored. I finally met Wendy Meade by chance (she came to one of my photography courses) who told me that she was a prison visitor. I took the opportunity to talk to her about my project. She then introduced me to a Deputy Governor who gave me an opportunity to explain in details what I was trying to achieve.

PP: Who is Wendy Meade?

JCG: Wendy is part of The Panel of Prison Visitors comprised of six volunteers, at present appointed by the Policy Council. They are an independent body authorised by the 1998 Prison Administration (Guernsey) Ordinance to pay frequent visits to the prison at any time of day or night. At least two members are required to visit at least once a month.

PP: What were the prisoners’ reaction to the project?

JCG: I think they didn’t know what to expect first. They took the opportunity to join the group as they had nothing else to do..

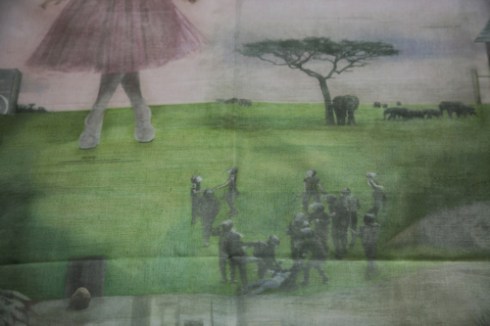

Very quickly they started to get more and more involved. The course now is completely oversubscribed with a long waiting list. One of the first reactions that I always get is, “What do you want us to photograph? There is nothing interesting here.” I see my role as teaching them to see and look in a different way.

PP: What was the staff’s reaction to the project?

JCG: The course created lots of challenges for the staff as I didn’t want to stay inside the classroom. I needed to have access to every single corner of the prison. In this special environment having a group of prisoners walking around with cameras on hands is obviously a logistical nightmare. The administration finally came up with an idea of having a dedicated security officer who walks around with us everywhere.

I have a great respect for the staff. Their job is not easy and can be very stressful but their attitude has always supportive and helpful. There is nothing we can do without their help so it was important to gain a level of trust but also share some understanding.

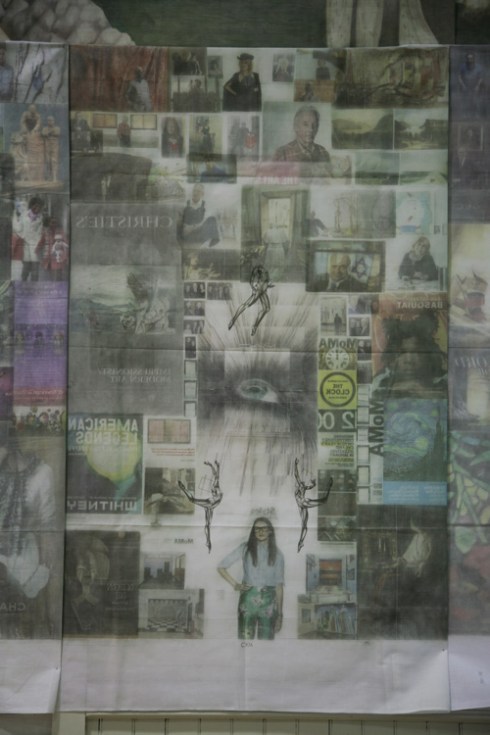

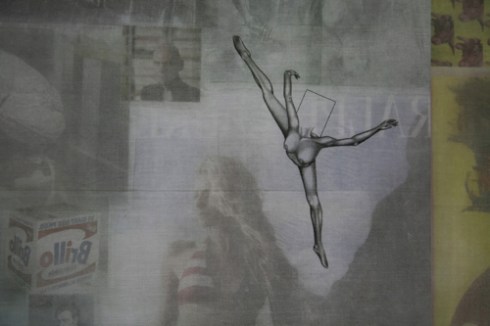

PP: You made over 2,000 pictures for the third iteration of the project and edited those down to 40 for the exhibition. Can you tell me about the editing process?

JCG: We did a couple of sessions with the prisoners where we looked at the photos and decided which ones worked best and why. We didn’t have access to computer inside the prison so I processed all the photos in my studio and did the final editing.

My hope is to give prisoners a way to express themselves, building their self-esteem and reaching a sense of achievement and proud in what they managed to produce. I occasionally meet some of them whose been released. When they tell me that they are still taking photos or saving to buy a new camera, it makes my day.

PP: Thanks Jean-Christophe

JCG: Thank you, Pete.

EXHIBITION

Presented by the Guernsey Prison in collaboration with the Guernsey Photography Festival, Inside View was first exhibited in November 2013, at the Guernsey Prison Visitors Centre. Inside View is on show from 20th of March – 4th April 2014, at the Gatehouse Gallery, Elizabeth College, The Grange, St Peter Port, Guernsey GY1 2PY

AWARD

Inside View was awarded the Koestler Trust’s William Archer Platinum Award for photography, which attracts more than 5,000 entries from offenders across the UK. The Trust promotes the arts in special institutions, encouraging creativity and the acquisition of new skills as a means to rehabilitation.