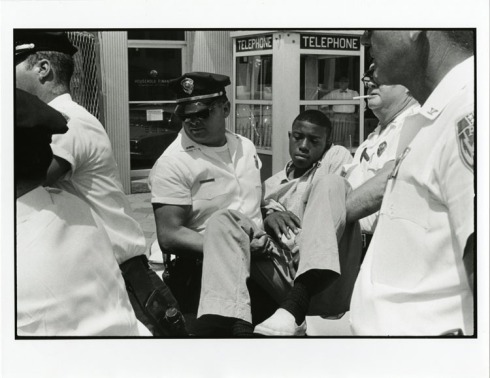

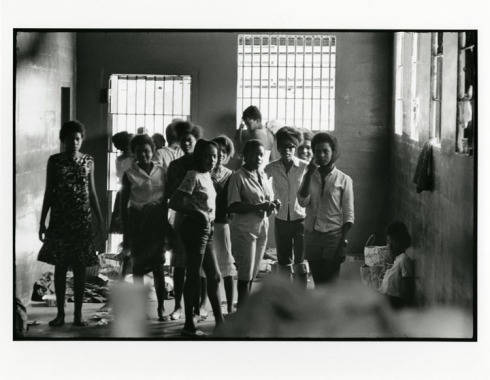

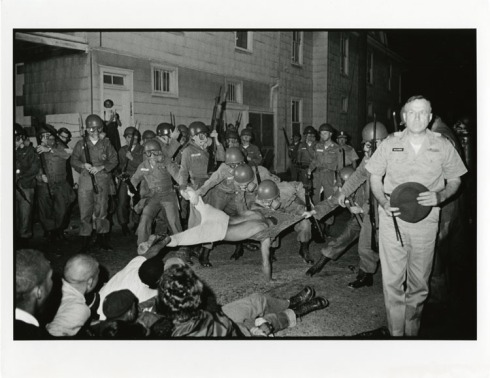

May 4th, 2009. 9:19pm: Guards pushed down on Messier’s back, pressing his chest toward his knees, “suitcasing” him, a dangerous tactic banned in prisons. Image courtesy of Boston Globe.

The title of this post makes it sound like I’ll be making a habit of recording these stories of abuse. I will not — there are too many.

The title of this post is also the slightest of variations on the title of a post I published yesterday. Again, I want to reiterate that episodes of abuse (particularly behind closed prison gates) are not irregular. I simply don’t have the time to catalogue them all.

This week, two particularly glaring cases of state violence inside prisons were reported. The first is a return to a 2009 murder by Massachusetts prison guards. The second, a prison doctor in California sterilising female prisoners without consent.

GUARDS RESTRAIN PRISONER, STAND NEXT TO HIM WHILE HE DIES

The murder of Joshua Messier is a murder that, in terms of legal language, is no longer. Guards killed Messier with rough restraint techniques. The medical examiner called it homicide, but later changed that verdict saying Messier’s initial violent outburst (due to his schizophrenic attack) meant he was to blame for his own death.

Prison guards put Messier into restraints and “suitcased” him meaning two officers put all their weight on Messier’s back while he was in a kneeling position. It is illegal control technique because of the risk of suffocation. Messier never moved when he came out of restraint. The guards stood idly around for 10 minutes. Messier stopped breathing, his face turned blue and he died in front of them. It took a nurse to notice something wrong before medical aid and CPR was delivered but by that time it was to late.

Multiple shocking aspects stack up in this case. Bridgewater State Hospital is the only facility in Massachusetts designated to hold mentally-ill patients, and yet no guards have specialised psychiatric training. Bridgewater imprisons mentally-ill men with behavioural issues alongside convicted violent criminals. Messier, like others mentally-ill in Bridgewater, had not been charged with a crime — he had assaulted staff in a hospital during a earlier schizophrenic episode and was placed in prison as a result.

Criminal charges should be brought against the officers involved. For the sake of justice and for the sake of trust in a system that seems, right now, to care more about covering its own ass than protecting the vulnerable.

Excellent reporting by the Boston Globe:

Yet, nearly five years after his death, no one at Bridgewater State Hospital has been prosecuted or even punished, and all but one of the guards still works for the Department of Correction. Officially, the department maintains that no excessive force was used and that everything the guards and nurses did that night was “done in accordance with standard procedure.”

My thoughts to Joshua Messier’s family.

FEMALE PRISONERS IN CALIFORNIA STERILISED WITHOUT CONSENT

For those who pay particular attention to the invisible abuse behind American prison walls, the story of Dr. Joseph Heinrich’s abuse of California female prisoners will not be entirely new. In July, Corey G. Johnson, reporting for the Center for Investigative Reporting broke the story that California Department of Corrections (CDC) doctor Heinrich and his staff had carried out at least 132 unauthorised tube ligation (tube-tying) procedures.

Between 2006 and 2010, doctors under contract with the CDC, sterilized women without the required state oversight and approval. These vulnerable women were basically misinformed or bullied into sterilisation. The women were signed up for the surgery while they were pregnant and housed at either the California Institution for Women in Corona or Valley State Prison for Women in Chowchilla, which is now a men’s prison.

Based on information in state documents and interviews, Johnson suggested in July that perhaps there were 100 or more similar cases — and victims — dating back to the late 1990s.

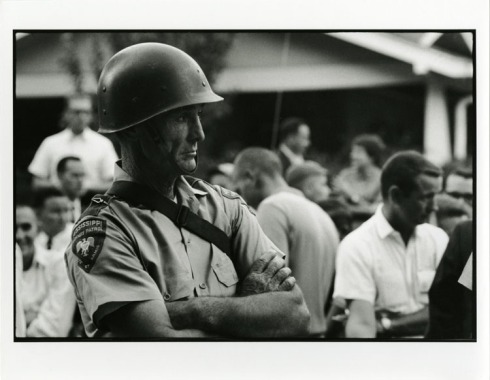

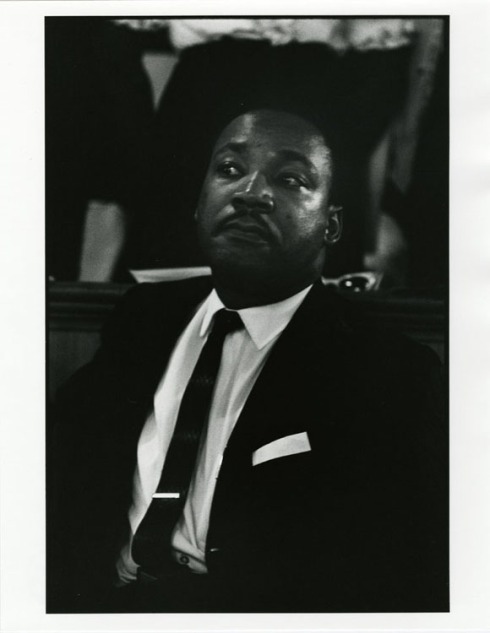

Female patients have accused Dr. James Heinrich, shown in 2007 at Valley State Prison, not just of trying to dictate their reproductive decisions, but also of unsanitary practices and botched surgeries that injured them and their infants. Credit: National Geographic. Source: Fresno Bee.

Johnson returned this week reporting on Heinrich’s history of unsanitary practice and a catalogue of complaints against him, including but not limited to, eating popcorn during examination of patients.

Heinrich arranged an unusually high number of other sterilization procedures including hysterectomies, removal of ovaries and endometrial ablations. In total, 378 procedures at Valley State Prison between 2006 and 2012. These figures alarmed federal authorities, which are now in oversight of the entire medical care system in California prisons.

In 2006 alone, Heinrich arranged for 23 inmates to have their tubes tied – the most ever for a California women’s prison in a single year since sterilization records began being kept in 1997.

Despite his history of accusations of unsanitary practices and botched surgeries that injured women and their infants, Heinrich was not only hired by the prison system, but also kept on after the federal receiver was appointed to bring to the prison’s medical system into compliance with constitutional rights. Johnson reports:

“Heinrich retired from Valley State Prison for Women in 2011 after six years, during which his total annual pay reached a high of nearly $237,000. Federal authorities rehired Heinrich as a contract physician, and he continued treating inmates at Valley State though December 2012. Since then, he has not worked at the prison.”

I repeatedly complain that events behind prison walls go unnoticed and that abuses go unreported. Corollary to that is the fact that abusive staff seem to be able to act with impunity, for years, as compared to practitioners on the outside. I do not know what the solutions would be. But I have a suggestion that would be a move in the right direction: Give tax-payers the right to visit prisons and “oversee” their tax dollars at work.

Ralph Nader (a long-time proponent for sensible discussion on U.S. prisons) wrote last month, that American tax-payers should be allowed access to the prisons. This is not a ridiculous suggestion. Prisons are safe places to visit. Public visitation would not only keep authorities accountable, but would tackle stereotypes among the public, educate the public and by virtue of more porous movement improve transparency and procedures. Some prisons, such as San Quentin in California, regularly gives public tours to media professionals, academics, students and law enforcement cadets. Nader’s proposal was based upon the practices of independent monitors in U.K. prisons.

Of course, it would be wholly inappropriate to sit in on a doctors visit inside or outside of prison. Prison hospitals are within walls within walls. Rogue doctors must not find protection inside already unsafe institutions. The California Department of Corrections must be held accountable for the extended hire of Heinrich, a man who one patient says treated her “like a cow.” The details provided by others formerly under his care are shocking. Heinrich is currently under official federal investigation, the details of which are unknown.