You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘California’ tag.

I wanted to trace the physical and psychic contours of the world of these young people to see what they might reveal. Juvies is not only a document, but also a query about perception. Do we know who these young people are and what we are doing to them?

Ara Oshagan

The Open Society Documentary Photography Project launches Moving Walls 17 exhibit today. Ara Oshagan, one of the seven award recipients, alerted me to the New York launch and his inclusion, Juvies: A Collaborative Portrait of Juvenile Offenders.

Juvies is collaborative because often his images are accompanied by the handwritten texts of incarcerated young people. Frequently the writings focus on emotional ties, problems with self esteem, the powerlessness against a system. It makes sense then that many of Oshagan’s photographs are visually-fractured, detached.

Compositions of door-frames, window reflections, outside corridors and gestures to action the other side of barriers describe very literally the immediate limitations these young people face daily. Oshagan’s work is not to politicise, but to describe (as best that is possible in the manipulating medium of photography.)

Oshagan explains, “I did not meet any angry or tattoo-ridden kids decked out in the clothes and accessories that could mark them as members of the city’s gang culture. Rather, I found a group of ordinary young men and women who had signed up for a video production class. When I spoke to them, they were deferential. For them, candy was the “contraband” article they had brought to class. Some of the kids were interested in photography and told me about how they strove to learn white balance. I listened to one of the kids play Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” on [a keyboard]. And somehow I had come full circle: I had played that exact same piece to my own son the night before. Suddenly, the distance between the inside and the outside seemed to vanish into thin air, a vast gulf turned into an imperceptible chimera.”

PHOTOGRAPHING INSIDE

Before accompanying filmmaker friend, Leslie Neale* into Los Angeles County Juvenile Hall, Oshagan wasn’t an activist or particularly interested in prison reform. Oshagan admits the exposure to the system and young lives within was disorienting. From Oshagan’s artist statement:

“I was in a privileged place that allowed the perceptions that existed in my head to be confronted by the realities I was witnessing in the closed and misunderstood world of incarceration. What I was seeing was also raising issues that would not give me peace.”

“I can understand why Mayra might get life in prison for shooting her girlfriend from point blank range. But how could a combination of relatively minor charges result in the same life sentence for Duc, an 18-year-old who, despite having no prior convictions, was convicted in a shooting crime that resulted in no injuries and in which he did not pull the trigger? And why did Peter – a 17-year-old piano prodigy and poet – get 12 years in adult prison for a first time assault and breaking and entering offense? Why is the justice system so harsh on kids who clearly have potential?”

PHOTOGRAPHING OUTSIDE

In addition to the walls, the guards, the other incarcerated people, the yards, the bunk beds, Oshagan also photographed families and communities left behind as well as the courts and victims. Sadly, I cannot present these images here but consider them essential in Oshagan’s “layered photographic narrative”.

These young people cannot be ignored. Our actions, just as theirs have ramifications both sides of the walls.

Two weeks ago the Supreme Court of the United States of America changed law, ruling life imprisonment without parole (LWOP) for a non-capital offense by a juvenile was to be removed from the books. Get past the fact that such harsh punishment was illogic and cruel and one soon arrives at the maddening circumstances of some of Oshagan’s subjects, Duc.

High school student Duc was arrested for driving a car from which a gun was shot. Although no one was injured, Duc was not a member of a gang, had no priors and was 16 years old, he received a sentence of 35 years to life

Again, to quote Oshagan, “Do we know who these young people are and what we are doing to them?”

* Oshagan did the B-Roll for Neale’s documentary film Juvies, whose own words about the juvenile detention system are worth taking in.

BIOGRAPHY

Born into a family of writers, Ara Oshagan studied literature and physics, but found his true passion in photography. A self-taught photographer, his work revolves around the intertwining themes of identity, community, and aftermath.

Aftermath is the main impetus for his first project, iwitness, which combines portraits of survivors of the Armenian genocide of 1915 with their oral histories. Issues of aftermath and identity also took Oshagan to the Nagorno-Karabakh region in the South Caucasus, where he documented and explored the post-war state of limbo experienced by Armenians in that mountainous and unrecognized region. This journey resulted in a project that won an award from the Santa Fe Project Competition in 2001, and will be published by powerHouse Books in 2010 as Father Land, a book featuring Oshagan’s photographs and an essay by his father.

Oshagan has also explored his identity as member of the Armenian diaspora community in Los Angeles. This project, Traces of Identity, was supported by the California Council for the Humanities and exhibited at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in 2004 and the Downey Museum of Art in 2005. Oshagan’s work is in the permanent collections of the Southeast Museum of Photography, the Downey Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art in Armenia.

MOVING WALLS 17

Also supported by the Open Society Documentary Photography Project are Jan Banning, Mari Bastashevski, Christian Holst, Lori Waselchuk & Saiful Huq Omi and The Chacipe Youth Photography Project.

The CDCr has just released REPORT 2009-107.2 SUMMARY – MAY 2010. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: Inmates Sentenced Under the Three Strikes Law and a Small Number of Inmates Receiving Specialty Health Care Represent Significant Costs

The report states the obvious. Three Strikes is expensive (and I’d add it is no deterrent) and health care costs are huge and dominated by a minority (aging) group. To quote:

Our review of California’s increasing prison cost as a proportion of the state budget and California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s (Corrections) operations revealed the following:

Inmates incarcerated under the three strikes law (striker inmates):

– Make up 25 percent of the inmate population as of April 2009.

– Receive sentences that are, on average, nine years longer-resulting in about $19.2 billion in additional costs over the duration of their incarceration.

– Include many individuals currently convicted for an offense that is not a strike, were convicted of committing multiple serious or violent offenses on the same day, and some that committed strikeable offenses as a juvenile.

Inmate health care costs are significant to the cost of housing inmates. In fiscal year 2007-08, $529 million was incurred for contracted services by specialty health care providers. Additionally:

– 30 percent of the inmates receiving such care cost more than $427 million.

– – –

While stresses on the prison system in California are particularly acute, they are not untypical. Three Strikes laws have been a failure across the US, and still exist in the 24 states that enacted them in the mid-nineties.

Over two million individuals are behind bars in U.S. prisons, living in isolation from their families and their communities. Prison/Culture surveys the poetry, performance, painting, photography & installations that each investigate the culture of incarceration as an integral part of the American experience.

As eagerly as politicians and contractors have constructed prisons, so too activists and artists have built a resistance. Nowhere are these two forces pushing against one another as forcefully as in California. The book, Prison/Culture, compiles the documents of a two year collaboration between San Francisco State University, Intersection for the Arts (one of San Francisco’s oldest art non-profits) and prison artists & outside activists across the US.

Mark Dean Johnson’s essay summarises the visual/cultural history of incarceration; from Gericault’s institutionalized mentally ill subjects and his paintings of severed heads as protest against capital punishment, to Goya’s prison interiors of the inquisition; from Alexander Gardner’s portrait of Lincoln’s assassin Lewis Payne (1865), to Otto Hagel’s portrait of Tom Mooney (1936); and from Ben Shahn’s murals against indifference to the conditions of immigrant workers (1932) to the work of Andy Warhol and David Hammons in the modern era.

Johnson guides this lineage to the Bay Area, describing how Michel Foucault’s book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison became the conversation topic of Bay Area coffeehouses and classrooms (Foucault began lecturing at UC Berkeley in 1979). The swell of interest in Foucault’s structuralism coincided with a grassroots expansion of prison art in the early 1980s.

For text, the editors of Prison/Culture made two canny and provocative choices: Angela Y. Davis and Mike Davis (no relation).

THE TEXT

Firstly, in a 2005 interview, America’s most notorious prison abolitionist Angela Davis sets out – in her most accessible terms – how our prison industrial complex serves primarily as a tactical response to the inadequate or absent social programs following the end of slavery. Abolition was successful in that it redefined law, but it failed to truly develop alternative, democratic structures for racial equality. Powerful stuff, yet even newcomers to Davis’ argument won’t be as shocked as they may expect to be. She’s that good.

Next up, Mike Davis’ 1995 essay ‘Hell Factories in the Field’ is a bittersweet ‘I-told-you-so’-inclusion. Davis has made a specialty of dealing with – in stark academic prose – disaster scenarios, race-based antagonism and the environmental rape of recent Californian history. When Davis witnessed the mid-nineties expansion of the prison industrial complex (or as Ruth Gilmore Wilson terms it ‘The Golden Gulag’) he foresaw prisons’ economic band-aid utility for depressed towns; foresaw the mere displacement of violence; foresaw the assault on fragile family ties; foresaw the unconstitutional prison overcrowding and predicted the collective collapse of moral responsibility.

Davis’ article focused on the then new California State Prison, Calipatria – and not in a dry way. Paragraphs are devoted to recounting the installation of the world’s only birdproof, ecologically sensitive death fence following impromptu electrocutions of migrating wildfowl. The editors note, as of 2008, Calipatria’s facility design of 2,208 beds was 193% over-capacity with 4,272 inmates. Where birds saw an improvement in their lot, prisoners certainly did not, have not.

THE ART

Contributors include some well-known names – RIGO, (here on PP) Sandow Birk, Deborah Luster and Richard Kamler whose works address incarceration, criminal profiling, wrongful conviction, prison labor, and the death penalty. The book also includes poetry by Amiri Baraka, Ericka Huggins, Luis Rodriguez, Sesshu Foster and others but I shall not comment on these wordsmiths (their work is beyond my purview) other than to say they are talented and politically in the right place.

Special mention must go out for Deborah Luster’s One Big Self project (more here). In my personal opinion, it is the single most important photographic survey of any US prison. It is certainly the most longitudinal. Over a five year period, Luster visited the farm-fields, woodsheds, rodeos and national holiday & Halloween events throughout Louisiana’s prisons. She became a loved and recognized figure among the prison population; she estimates she gave away 25,000 portraits to inmates. Luster’s conclusion? Even mass photography struggles to communicate the vast numbers of men and women behind bars.

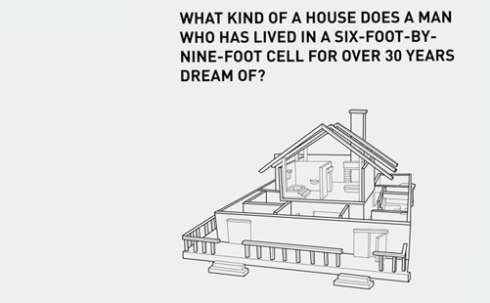

In 2003, artist Jackie Sumell collaborated with Herman Joshua Wallace (one of the Angola 3) on the design of his “Dream House”. The project The House That Herman Built is heartbreaking and bittersweet.

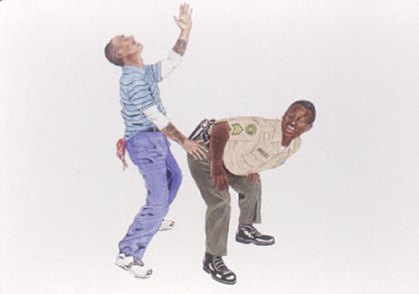

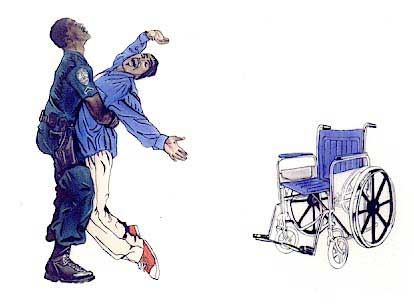

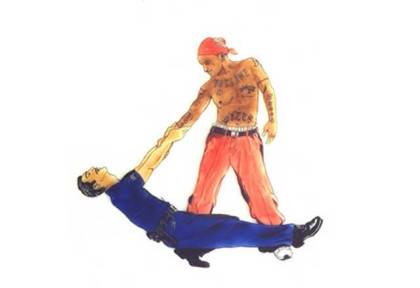

Alex Donis employs cunning and cutting humour for his series WAR. He sketches criminal “types” with figures of authority (policemen, prison guards) mid-dance, often bumping and grinding. He even conjures a kiss between Crips and Bloods gang members.

Also unexpected is the visual testimony of condemned mens’ last requested meals. For The Last Supper, Julie Green painstakingly painted porcelain plates with the last meals of nearly 400 executed men. Grayson Perry won the Turner Prize a few years ago, in large part due to his vases of abuse, bigotry and social ills. This clever use of regent materials has also been adopted by Penny Byrne for her Guantanamo Bay Souvenirs which sets up interesting parallels and a new turn for discourse between US homeland prisons and those used for the “Global War About Terror” (GWAT).

Relating to GWAT, Aaron Sandnes established a sound sculpture in which gallery visitors were subjected to the same pop songs used in Psych-ops by police and military interrogators.

Dread Scott‘s use of audio is intentionally to give silenced men a voice. (Scott has talked about the primacy of audio in his exhibition of prison portraits previously at Prison Photography).

Mabel Negrete collaborated with her brother incarcerated in Corcoran State Prison. She mapped out the floorplan of his cell as compared to her apartment bathroom. She then developed a dramatic dialogue in which she played both herself and her brother. (No images unfortunately.)

Traced – but essentially fictional – lines of structure are fitting for San Francisco, the city in which world-famous architect/installation artists Diller & Scofidio got their start with the architectural memories of the Capp Street Project. Negrete’s CV is extensive, she was instrumental in organising Wear Orange Day, a prisoner awareness action. Also check out her Sensible Housing Unit.

Cross-prison-wall collaborations are vital to the project as a whole; so much so, that without input from prisoners, the entire enterprise would fall short. Primarily, it is the men of the Arts in Corrections: San Quentin run by the William James Association who deliver acrylics and oils of optimistic colour and profound introspection. More here.

Collaboration as delivered in a multimedia and digital format comes by way of Sharon Daniel’s Public Secrets. Public Secrets “reconfigures the physical, psychological, and ideological spaces of the prison, allowing us to learn about life inside the prison along several thematic pathways and from multiple points of view.”

In closing, it is worth noting that San Quentin prison (only 12 miles north of San Francisco) has one of the few remaining prison arts programs in the state following 20 years of cut backs. The works in Prison/Culture challenge – as Deborah Cullinan & Kurt Daw, in their foreword, suggest – “traditional boundaries between inside and outside, between professional and amateur, between institutions and people” and, “by juxtaposing work by professional artists with artists who are working inside a prison, this book challenges us to rethink notions of community and culture.”

Prison/Culture is simultaneously a consolidation of achievement, a fortification of resources and celebration of resistance. This may be a book with a Californian focus, but it has national and international relevance. Succinct, well researched, egalitarian and lively. For me, Prison/Culture is the best collection of works by any US prison reform art community up until this point in history.

The resource list of over 80 organisations at the back of the book (page 92) is ESSENTIAL reference material for anyone looking to commit energies into prison art programs. All told, this book is a must read for those interested in the artistic landscape of our prison nation. It powerfully exposes the vast gulf between criminal justice and social justice in US society.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Prison/Culture is published by City Lights, edited by Sharon E. Bliss, Kevin B. Chen, Steve Dickison, Mark Dean Johnson and Rebeka Rodriguez.

Read a Daily Kos review here, and view images from a 2009 exhibition here.

City Lights Celebrates the Release of Prison/Culture

On Thursday, May 6 at 7:00 pm, join Steve Dickison, Jack Hirschman, Ericka Huggins, and Rigo 23 for a reading and book release celebration at City Lights Books. Tune in to KQED Forum at 9:00 am PDT the morning of the event for an interview with the book’s editors and contributor Angela Davis.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Images (from top): PRISON/CULTURE book front; Sandow Birk; Deborah Luster; Exhibition views of The House That Herman Built; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Alex Donis; Julie Green; Julie Green; Ronnie Goodman, San Quentin inmate, displays his work; and ‘Public Secrets’ screenshot.

The governator wants to outsource California’s prisons to Mexico. Arnie went totally off script and blurted out an idea not even Matthew Cate, Secretary for the California Department of Corrections could, or would, back up.

Schwarzenegger suggested that outsourcing would save California $1billion/year, but couldn’t state from where he got the figure.

The idea is a non-starter for so many reasons. I know Arnie is desperate for solutions but he must at least be expected to stay within the realms of reality, no?

In a loose tangential thread, I have been impressed recently by the works of Livia Corona and Alejandro Cartagena.

Corona and Cartagena both train their lenses on suburbia, not prisons (although the psychologies of the two architectures may converge?)

On the evidence of their photographs the construction industry in Mexico is booming, even if it is ugly.

© Livia Corona. From the series, 'Two Million Homes for Mexico'

© Alejandro Cartagena. From the series, 'Fragmented Cities'

Thanks to Katie DeGraff for the tip off on Arnie’s madness

Belva Cottier and a young Chicano man during the Occupation of Alcatraz Island, May 31, 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

Today marks the fortieth anniversary of the start of the Indian Occupation of Alcatraz, an action that lasted over eighteen months until June 11th 1971.

Photographic documents of the time are surprisingly scant. Over the past few decades, Ilka Hartmann‘s work has appeared almost ubiquitously in publications about the Indian Occupation. We spoke by telephone about her experiences, the dearth of Native American photographers, the Black Panthers, Richard Nixon, the recent revival of academic research on the occupation and what she’ll be doing to mark the anniversary.

Your entire career has been devoted to social justice issues, particularly the fight for Native American rights. Did your interest begin with the Alcatraz occupation?

No, it began earlier. I came the U.S. in 1964 and that was during the human rights movement. I was a student at the time but I really wanted to go and work with the Native Americans on the reservations of Southern California. I was connected to the Indian community here through a friend who had emigrated to California earlier. I learnt very early about the conditions for American Indians. It reminded my of what I had learnt as a teenager about Nazi rule.

When the occupation began I wanted to go but I couldn’t because I was not Native American, but I waited until 1970.

Concurrently you were photographing the Black Panther movement – centered in Oakland – and the other counter culture movements of the late sixties in the Bay Area. How did they relate to one another?

They were all the same, each group struggling to advertise their conditions, the police brutality and the lack of educational and cultural institutions. I was involved in the fights for American Indians, African Americans, Chicano and Asian Americans in Berkeley. We were protesting as part of the Third World Strike. For me everything was connected and it was the same people who were speaking up later at Alcatraz.

My new book is actually about the relations between the different groups of the civil rights movement. There was a lot of solidarity between groups. The Black Panther Party understood this. Many people think that the Black Panthers were concentrated on their own politics but they understood solidarity and got a lot of help from non-Black people. If you look at my pictures of the Black Panther movement a lot of supporters were the white students of Berkeley. There is a saying, “The suffering of one, is the suffering of everybody”.

In the Bay Area people were so willing to help the Indians at Alcatraz and help in the Black Panther movement and they really felt things were going to change.

I was a student at UC Berkeley and stopped in February 1970. I went to Alcatraz in May of 1970. I had learnt to open my eyes and emotions at UC Berkeley through all the different groups we had.

How many times did you visit Alcatraz during the occupation? And how long did you stay each time?

I only went twice to the island. It is funny because I didn’t even know if my photographs would turn out. I had a camera that I’d borrowed from a friend with a 135 mm Pentax lens … and also a Leica that a friend have given me too. But I didn’t have a light-meter for the Leica so I didn’t know if the photographs I took in the fog would come out. It was so light. I was amazed that they came out. I also went over in a small boat that same year.

So I made contact sheets and tried to get them published which was a big problem because you had to really work on that. My first picture of the occupation was published in an underground paper called the Berkeley Barb then in June 1971 I was at KQED, a Northern California Television station, for an interview with an art editor. I had hitch-hiked there from the area north of San Francisco and I just opened my box of pictures to show him topics I was concerned about when over the intercom came an announcement “The Indians are being taken from Alcatraz.”

I saw some video guys run by, I grabbed my bag and camera and asked them if I could join them. They said, “Yes, ride with us and say you are with us.” We got into an old VW and drove around on the mainland to see the occupiers and that is how I got those shots of the removal. It was an incredible coincidence because I actually lived far from the city. It’s quite incredible. I only went two times during the occupation and then I got those shots afterward.

From then on I made contact with people and in that year I showed my pictures at an Indian Women’s conference, making very good friends with people in the American Indian movement. From then on I went to cultural events, powwows and so on and my pictures appeared in the underground press. I wrote articles and people contacted me for images. That’s how I made the connection.

So really you made no arrangements?

I didn’t make any arrangements. I followed everything from the first day in the papers and on that day in May … on May 30th the Indians asked all the journalists to go and I wanted to be there. That’s how it all started; they invited us there that day.

Did you realize at the time how profound an historical event it was?

Yes, I always felt how important it was. This was the first time they [Native Americans] spoke up. All over the world people wrote about it and the cause became known globally, and especially known in the United States. I believed in it … I still do.

What are your lasting memories of your time and work during the occupation?

It was a prison that had been closed so it was surrounded by barbed wire fence. Some of it had become loose and I took some pictures. The wire swung loose in the air and there was a sound across the island of the wind whispering over it. And if you looked out over the beautiful waters, you really got the sense – with the barbed wire – that the Indians were prisoners, as well as occupiers of the Bay. Prisoners of the Bay; which means prisoners of the World. In that sense I really had a strong feeling of the prison.

How did you react to the environment?

For me, strangely, the experience of going to Alcatraz has always been a very high and wonderful experience. It is hard for me to even explain. Of course I know it was a prison. On the tour of Alcatraz I got very upset, especially during the part when you’re taken downstairs to learn about the lesser known incarceration of Elders and also the cells for those people who didn’t want to go to war. So of course I know it is was a prison, yet when I go there I am struck by exuberance and hope about [Indian] people being able to make statements about their conditions.

I was a witness to that and wanted to be a conduit for those statements. There were no American Indian journalists, we were nearly all white. There was one Indian photographer, John Whitefox, who is now dead. But he lost his film. So we really saw it as our job, politically, as underground photographers and writers to cover what was part of the revolution and social upheaval.

Eldy Bratt, Alcatraz Island, May 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

Two Indian children play on abandoned Department of Justice equipment. Alcatraz Island, 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

San Francisco Bay has a strange history with islands, incarceration and subjugation. San Quentin was the focus of the Black Panther resistance – it is just ten miles north of the city. Angel Island was an immigrations station for Asians – it is known as the “Ellis Island of the West” and some Chinese migrants were kept there for years. And, then there’s Alcatraz. How do you reconcile all this?

It’s totally horrible to me. I come form Germany. Before I came I’d heard about Sing Sing on the river on the East coast. It was a horrible thought to me that they could put people in such prisons.

I drive past San Quentin most days, I have actually been inside and taken photographs. And of Angel Island – it is almost sarcastic to imprison people like that; it’s such a contradiction to the beauty of the Bay. It’s the hubris of human beings to do that to one another.

Of course there are people who should be in prison, like at San Quentin, but certainly the Chinese should not have been treated like that on Angel Island. The Indians and the anti-war demonstrators should absolutely not have been treated like that on Alcatraz. Actually the authorities were respectful to the antiwar demonstrators than they were to the Indians, but still both are an aberration of human nature to treat others like that. I don’t know what to do with murderers but I do know I am against the death penalty.

An Indian man arrives at Pier 40 on the mainland following the removal in June 1971. Indians of All Tribes operated a receiving facility on Pier 40, where donated materials were stored and where Indian people could wait for boats to transport them to Alcatraz Island. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

"We will not give up". Indian occupiers moments after the removal from Alcatraz Island on June 11, 1971. Oohosis, a Cree from Canada (Left) and Peggy Lee Ellenwood, a Sioux from Wolf Point, Montana (Right). Photo © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

How do you see the situation for Native Americans today?

When I started there was said to be one million American Indians and now statistics say there are one and a half million. This is down to two things: first, the numbers have increased, but secondly more people identify as Native Americans where they had tried to hide it before due to racism and prejudice.

I went on one trip with a Native American Family for six weeks across the southwest and I kept asking if the Indians were going to survive and there was some doubt, but now people really think the culture is growing and there has been a notable revival. There advances being made dealing with treatments for alcoholism and returning to free practices of traditional worship. I know that the Omaha are talking of a Renaissance of the Omaha culture. My friend and historian, Dennis Hastings, who was also an occupier of Alcatraz, said to me ten years ago “It could still go either way. Half the Native peoples are debilitated with alcoholism and the other half are vibrant and healthy.”

Great afflictions still exist but there are many more Indians who are able to function in the Western aspects of society and traditional ways of life. When I entered the movement there was only one [Native American] PhD; now there are over a hundred. There is hope now.

What we felt came out of Alcatraz was the influence that it had on Nixon. Because he was a proponent of the war I always used to think of him in only negative ways but that is a learning experience too. It is a shock that someone responsible for the deaths of so many people in the world, of so many Vietnamese, could do something good. He signed the American Indian Religious Freedoms Act (1978). Edward Kennedy also worked a lot on these laws.

We believe the returns of lands such as Blue Lake/Taos Pueblos in New Mexico and lands in Washington followed on from the occupation of Alcatraz. There is a famous picture of Nixon with a group of Paiute American Indians. I believe a former high school sports coach of Nixon’s from San Clememnte was Native American and so we think this teacher influenced him.

As a result of Alcatraz, as well as the land takeovers, the consciousness has been raised among non-Indians and this was very important. People in the Bay Area were very supportive of the occupation, until the point where people were not responsible; it got messy the security got too strong and there were drugs and alcohol. Bad things did happen but in the beginning all that was important to expose to the world was written about, particularly by Tim Findley and all the writers working to get this into the underground press.

Until about 15 years when Troy R. Johnson and Adam Fortunate Eagle wrote and researched their books we didn’t understand everything that had happened – we just knew it was exhilarating. We now have the information of policy changes and the knowledge of people who went back to the reservations; leaders such as Wilma Mankiller who was the principle chief of the Cherokee for a long time. Dennis Hastings was the historian of the Omaha people and brought back the sacred star from Harvard University.

Many people have done things to allow a return to the Native culture and it is so strong now – both the urban and reservation culture. American Indians are making films about urban America – part of modern America but also within their Indian backgrounds. Things have changed enormously.

The benevolence of Richard Nixon is not something I’ve heard about before!

Yes, You can read more about it in our book.

What will you be doing for the 40th anniversary?

I’l be going to UC Berkeley. I’ve been working on an event with a young Native American man who is part of the Native American Studies Program which was established in 1970 as a result of the Third World Strikes. I walked and demonstrated at that time many times. I’m very happy to be returning. LaNada Boyer Means who was one of the leaders of the occupation will be present. We’ll be thinking of Richard Aoki, who was a prominent Asian American in the Black Panther movement, who died just a few months ago.

When these people would lead demonstrations, I would photograph it and then I’d rush to the lab, work through the night to get them printed the next day in the Daily Cal and then have to teach my classes and then take my seminars and it would go on like that for weeks.

So, a young man Richie Richards has organized a 40th Anniversary celebration at Berkeley. It includes events that will run all week, films, speakers, I’ll be showing my slides and then on Saturday we’re going to Alcatraz for a sunrise ceremony. Adam Fortunate Eagle, who wrote the Alcatraz Proclamation, will lead the ceremony on the Island.

In addition at San Francisco State where the 1969 student protests originated their will be a mural unveiled to mark the occasion. There have already been recognition ceremonies for ‘veterans’ of the occupation this week in Berkeley and starting tonight there are events for Native American High School students from all over the area in Berkeley also. Interest has really rekindled recently. The text books have really changed so much and I think that is excellent for younger generations.

And many more to come …

Thanks so much Ilka.

Thank you, Pete.

_________________________________________

For this interview I used Ilka’s portrait shots from the occupation. There are many more photographs to feast on here and here.

Overcoming exhaustion and disillusionment, young Alcatraz Occupier Atha Rider Whitemankiller (Cherokee) stands tall before the press at the Senator Hotel. His eloquent words about the purpose of the occupation - to publicize his people's plight and establish a land base for the Indians of the Bay Area - were the most quoted of the day. San Francisco, California. June 11th 1971. Photo Ilka Hartmann

Spot us

I filmed Dave Cohn‘s breakthrough Talking Heads jam sesh in 2005. The atmosphere was electric. It was also in our front room. I knew him when he was an intern at Wired.

I was really pleased therefore when he returned to San Francisco after grad school with a head full of ideas and pocket full of cash to launch Spot.Us

Spot.Us uses a crowd-funding model to support journalism. It is “an open source project, to pioneer ‘community funded reporting.’ Through Spot.Us the public can commission journalists to do investigations on important and perhaps overlooked stories … All content is made available to all through a Creative Commons license. It’s a marketplace where independent reporters, community members and news organizations can come together and collaborate.”

In the Spot.Us early days, I suggested a Tip to the community that it produced reporting on the impact of the economic downturn on California prisons. The speculation in the wording of my tip is now outdated – even laughable. We know that the CDCr has more than struggled – it has hit meltdown. The CDCr’s fiscal crisis can only turn inmates loose without sufficient re-entry support.

The function of ‘Tips’ seems to be simply to register interest; they are pithy when compared to the ‘Pitches‘ which are constantly promoted and on the search for supporters. Spot.Us not only empowers ordinary citizens through the $20 donations it also has established partnerships with big media – most recently the New York Times for Lindsay Hoshaw’s story on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Prison Health Reporting

Prison Photography would like to encourage you all to support Bernice Yeung’s Prison Health Reporting.

Yeung explains the need for journalism, “Parolees without proper access to drug treatment, mental health and medical care could have potentially serious public health and public safety ramifications. This issue has attracted the attention of policy makers, prisons, doctors and social service providers, who are increasingly trying to connect parolees with medical care and social services upon their release.”

While my position on the broken and punitive prison system of the US is well known, I have hardly commented on the need for expanded reentry support programs.

I think public safety is a notion too easily manipulated and reduced to rhetoric when legislation is created, but it is a reality that must be objectively measured when former prisoners are released.

Yeung’s focus on the drug and mental health programs, the practitioners and clients, and their testimony is the right inquiry. Yeung’s work will crystallize the life-changing, damaging, shocking and (occasionally) redemptive effects of prisons on folk in our society. Any one of the stories she tells will be more worthy than the electioneers’ tough on crime doublespeak.

Here’s the latest from Bernice Yeung on the Spot.Us blog.

______________________________________________________

Spot.Us is a fantastic experiment and is a part of the puzzle to all of those questioning what the future of news reporting will look like. See what all the fuss is about here.

______________________________________________________

Image: The image above originally appeared in the Spot.US blog post Prisons & Public Health: Why Should You Care? It is uncredited. I am curious about the image, because I am not even convinced it is from an actual prison. I would guess that a closely-cropped black & white image including bars, an obscured face and a blinding source of outside light ticks all the right boxes for a photo illustration. Our brain is fooled by these visual cues.

In this case, the writing and the appeal are more important than the image and, if my reading is right, I understand why this image was manufactured. However, I could be completely wrong. I’d like to know the photograph’s back-story….

California Institute for Men at Chino, 2008 (Prior to Riot). Photo Credit: CDCR

Michael Shaw over at the excellent BAGnewsNotes pointed out a rather bizarre anomaly in our image-saturated world. There exist barely any photographs of the prison riot at the California Institute for Men at Chino that occurred this weekend.

Given that Shaw has his hand firmly on the newswire pulse of America I’ll take him at his word … photojournalist coverage of this significant riot was is scant.

I even think that the image Shaw presents is a concession; a still from film footage.

Today, the Los Angeles Times published this image showing the aftermath of the riot.

Photo: A view from outside the fence after weekend rioting at the California Institute for Men at Chino shows a dorm with a hole burned through its roof and a yard littered with mattresses and other debris. Credit: Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times

The BBC was quick to cover the riot. Most news sources framed the riot as a result of racial tension, but in truth those tensions only came to surface due to inexcusable and acknowledged overcrowding. In 2007, Doyle Wayne Scott, a former Texas corrections chief consulting on California prison security reported that overcrowding at the California Institute for Men at Chino created “a serious disturbance waiting to happen.”

Overcrowding is a problem that ignites other problems, and represents a serious issue that has no easy answers. Some prison reform activists would be wiling to see new (temporary) facilities built to ease the tensions, but this is an unlikely scenario as trust between they and the legislature, Governor’s office, CDCr and CCPOA is low. Recent history has taught us that when new prisons are built, they are filled and calls for more prisons follow. The solution is to change the laws that over the past two decades have warehoused increasing numbers of non-violent offenders.

One of the other depressing aspects to this story is that the racial tensions are apparently the result, partly, of enforced desegregation at Chino. Prison populations operate on strict codes and it would seem that top-down-enforcement of an anti-racist policy doesn’t change the attitudes of the men only agitates their existing prejudices, distrust and expected antagonisms toward one another.

My humble suggestion to work against these deep-seated hatreds would be to operate smaller facilities with immediate access to education programs. Sociological models taught as part of a basic curricula are revelatory for many prisoners. Many inmates, given the tools and the logic to explain their oppositions will identify other ways of seeing race.

It is true that some prisoners don’t want to rehabilitate, but they are in the minority. Often it is simply the case that race for this population has never been discussed in complex or nuanced terms.

Here’s some video of the aftermath.

Thanks to Scott Ortner and Stan Banos for the tips on this story.

I am away from the computer for the next week. Joseph Rodriguez will occupy much of my thoughts during that time. As I have said before, I’ll be returning to his work and method.

In the meantime, read his interview and watch his multimedia piece over at RESOLVE blog.