You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Guantanamo’ tag.

I just keep coming back to Edmund Clark‘s work. And his book isn’t even out yet. It doesn’t help when venerable folk like Jim Casper and Colin Pantall are spending time and energy on his efforts – most recently from Guantanamo.

(BTW, Pantall has been posing some really good questions and posting some really good photography these past few weeks.)

Anyway, upon returning to Pantall’s site I picked up this quote by Clark:

It seems to touch upon many of my frustrations with photography from Guantanamo. Many inventive photographers will find manouveurs to draw out a novel image at Camps Delta, X-Ray, Iguana and others. Of course it is worth remembering that the majority of photos coming out of Gitmo will be consumed by the masses through media served by newswire coverage relying on long lens images of faceless orange boiler suits.

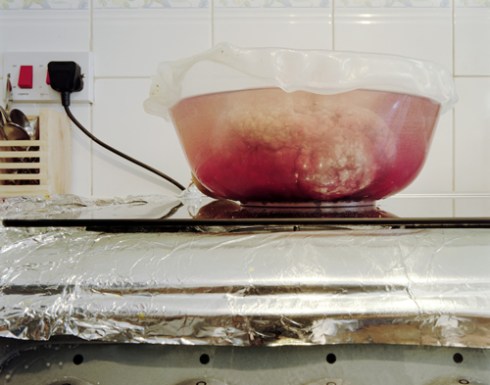

Clark has widened the scope of Guantanamo imagery by following the detainees to their homes and picking up on the underwhelming details of their “free” lives. The sterility and parallels between incarceration and home are sometimes frightening.

With Pantall’s permission I reissue Clark’s words here. Pantall interviewed Clark for the British Journal of Photography. (Underlining for emphasis is mine)

My last book was called Still Life/Killing Time and was about a prison in Britain. I’m interested in the themes of confinement and entrapment. Guantanamo Bay stands out as a symbol of confinement and my imagery is about the symbolism of that confinement. The starting point was going out with detainees who had been released and seeing how they were surviving. These people had been in prison for years, had never been charged but still had this massive label of being the worst of the worst stuck on them. I was interested in what their personal spaces said about them and if they were any traces of what they had experienced in Guantanamo.

Access was very difficult but started with their lawyers and slowly progressed to the point where I could photograph their homes. Once this was done, the second part was getting into Guantanamo itself. I applied to the Pentagon and made it clear I wanted to photograph both the American Naval Base side and the prison side. It took me 6 months to get clearance and then it was another 2 months before I went. Once I was there I was fortunate enough to get paired up with Carol Rosenberg, a journalist from the Miami Herald who had been reporting on Guantanamo since it opened as a prison. She knew how to deal with the Guantanamo media team (who were new in their jobs) and how to get past their obstruction.

I spent 8 days there in total, including 4 days on the naval base. It was like so many expatriate places, more American than America itself. It was interesting to look at the schools, the shops, the restaurants. It was like a little bit of America in Cuba, with reflections both of America and of entrapment; models of old refugee camps, a shrine to the Virgin Mary where she almost seems to be imprisoned, A Ronald MacDonald statue surrounded by fencing and wire. It looks like he’s banged up.

I don’t have any images of the detainees except for one – which shows a guard reflected in the cell window. But that’s not what my work is about. There is a lot of long lens imagery of Guantanamo showing the prisoners in their orange boiler suits, but I don’t know what that’s telling me. My work is about the spaces and what they evoke and how they relate to the spaces people live in once they have been released.

The work is about memory and control and dragging the work out of Guantanamo into where people are living now. I’m doing that through the edit of the 3 different spaces I photographed: the homes, the American Naval Base and the prison. When I got back, I started to edit the pictures in sequence as a narrative, but then I began to mix them up so you’re never quite sure where you are. I juxtaposed images, put one things together so one image sets off ideas that enriches the idea of what it is both to have been in Guantanamo, but also to have that experience inside you.

There are also strange details that I’m not sure off, such as the picture of the Duress button. We were told this was in an exercise room but we think it was one of the interrogation rooms and this was a panic button for the guards. Another picture shows a row of Ensure jars with a plastic tube next to it. Ensure is an energy drink they used to force feed hunger striking prisoners and the Americans had it on display to show their ‘duty of care’.

The detainees brought home and kept the strangest of things, a red cross calendar with the days ticked off. Only the best behaved prisoners would get this because there was a strategy of total disorientation. When prisoners first arrived they had no idea of where they were, what day it was or what time it was.

Then I looked at other bits of people’s homes, especially windows because in Guantanamo they have no windows with a view. There are no views. Being released and being able to choose what to look at, to have a view, is quite a thing. Sometimes people chose not to have a view.

I’m working with Omar Deghayes on an edit of all the letters he received at Guantanamo. When people received letters, they didn’t get the original, they got photocopies or scans of every page, even blank pages, including the front and back of the envelope, each page bearing a document number and a Guantanamo stamp.

All Images © Edmund Clark

AP Photographer, Brennan Linsley has visited Guantanamo twelve times in the past four years. Why? “My goal is to come back from each trip with a couple of shots that will allow me to paint more of a picture of this place'” says Linsley.

A journalist’s visit to Guantanamo is a frustrating experience – newsmen have a constant escort on a preplanned itinerary and must read and follow the fifteen pages of ground rules provided by the US military.

To offset these limitations Linsley chose repeated visits as a a tactic. In an attempt to humanise the detainees, he has weaved a photo-essay in-spite of Guantanamo’s milieu which is counter to all notions of free speech, experience and objective fact-gathering.

The British Journal of Photography has a brief but interesting interview with Linsley about his project.

This sequence of interactions between a Chinese detainee and photographers (described by Linsley) exemplifies the minutiae with which the US military must control the flow of information out of Guantanamo.

Just to get the juices flowing, Linsley closes the interview with this position, “The Golden Age of photography has been over for a long time. It died somewhere between the Vietnam War and the Gulf War.”

Discuss.

_______________________________________________________________

BJP’s interview coincides with Linsley’s work showing at the 2009 Visa pour l’Image at Perpignan.

For more images and links on Guantanamo see Prison Photography‘s Directory of Visual Sources.

His family claim he was 12 when he was taken into US custody. The pentagon claim he was 17. Whichever the case, the treatment remained the same.

Video from the Guardian.

… or put another way, the apparently unassailable problem that is Guantanamo only amounts to 2% of the actual problem.

This is only one of the many astounding facts I learnt from following the Guardian’s Slow Torture series.

I particularly valued this half hour podcast in which an expert panel of legal professionals discuss the cyclical, “odious” and often ludicrous procedures for trials based on ‘secret evidence’. Clive Stafford Smith has many valuable things to say about American legal protocols. He has represented detainees at Guantanamo Bay and says that, in the overwhelming majority of cases, ‘secret evidence’ used against terrorism suspects does not stand up to judicial scrutiny.

The majority of the Slow Torture series looks at British ‘secret evidence’ trials, how it affects the lives of terror suspects and the consequent erosion of Britain’s legal reputation:

The UK government’s powers to impose restrictions on terror suspects – without a trial – amounting to virtual house arrest have been condemned as draconian by civil liberties campaigners. In a series of five films, actors read the personal testimonies of those detained under Britain’s secret evidence laws and campaigners and human rights lawyers debate the issues raised.

Basically, the same problems embroiled in the acquisition and control of “sensitive” evidence exist on both sides of the Atlantic and are ultimately putting our societies at more of a long-term risk.

Photography alone is worthless. Interviews, think-pieces, investigation, theatre, video, debate, political fight and direct action make issues reality.

What are we to do with our Gitmo preoccupations when the real problem has been moved to Bagram, Afghanistan by President Obama?

This post is to salve the disappointment of thousands of visitors to Prison Photography that are tempted by the post titled View Inside Guantanamo: Video only to find that the Guardian’s rights to the three minute “tour” video have expired.

There exists a bristling irony in the Guardian’s curt and formal explanation of circumstance: the erasure of evidence based upon ‘rights’ pertaining to the command is an insulting reminder of the powerlessness of detainees whose lives are manipulated at will.

Paradoxically, in this case, it is the denied party that is the apologist for the US military’s enforced expiration and unavailability of material. It seems the controlled release of this footage has been trumped by its controlled withdrawal.

As a worthy (and non-governmental) alternative, Magnum offers Paolo Pellegrin’s 11 minute slideshow ‘Guantanamo‘. There are a few interesting things about this piece none of which are the actual photographs. The prints are steeped in morbid detachment and the unsurprising truth that the photographer was also controlled throughout this military prison.

The slideshow’s early description of Guantanamo as a small American town is sinister; the edited audio interviews of former UK detainees, family members, detainee lawyer and psychologist are very successful. The follow-up portraits of former detainees that Pellegrin later completed in Afghanistan are very strong.

All photos copyright of Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum Photos

Please, refer to my earlier post, for a comprehensive directory of photographic resources for Guantanamo including Bruce Gilden’s subtle flash-bulb mockery of Guantanamo’s rank and file. (Search within Magnum archives as deep-linking is impossible).

Update: Prison Photography collated a Directory of Photographic & Visual Resources for Guantanamo in May 2009.

- A detainee kicks a soccer ball around the central recreation yard at Camp 4, Joint Task Force (JTF) Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, June 10, 2008, during his daily outdoor recreation time. Detainees in Camp 4 get up to 12 hours of daily of outdoor recreation, including two hours in a central recreation yard. Photo Credit: U.S. Army 1st Lt. Sarah Cleveland

Just gratefully recieved a nudge from an urban conspirator to check out these 30 vetted photographs posted on the Boston Globe website. Obviously, many were taken during the same media tour I mentioned in the last post. Enjoy!