You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Photography’ tag.

Blake Andrews says, “Together with the mugshot, the passport snapshot was the earliest application of photography as purely personal identifier.” It’s a good read and you should check it out. My favourite observation was the 1920s transition, “Photos were glued instead of stapled.” Also, is that Indiana Jones?…

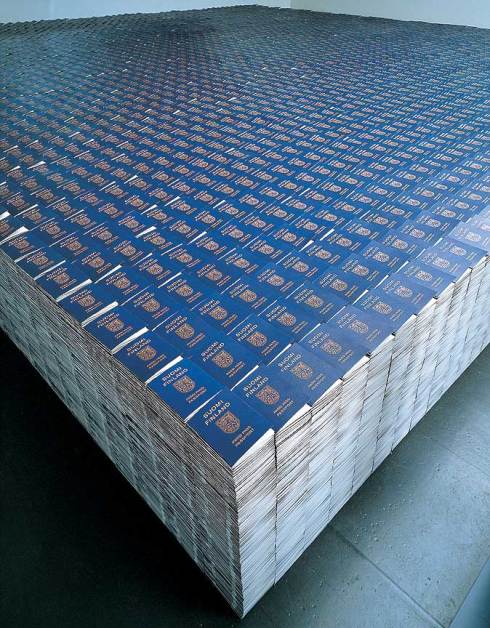

“One Million Finnish Passports”, 1995. One million replicated Finnish passports, glass, 800 x 800 x 80 cm. Installation view: Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki. Artist: Alfredo Jaar, courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

I’ve been thinking a lot about mugshots recently and how prison photography is one little orbit of many about the deathstar of dark-photography. Other orbits include Weegee, Larry Sultan & Mike Mandel (defining the cross over between documentary and fine art) forensic photography, police blotter, thanatourism, civil war hangings, Salgado’s “Beautiful Deathscapes”, lynching photography, Danny Lyon (the most appropriated of artists) and fetishism to name a few.

All of these, by method or subject, relate to the state, and thus more orbits of homeland and foreign surveillance, torture slideshows, death suites, electric chairs, driving licenses, mafia movies, Jenny Holzer and genocide.

The most everyday instance of a photographic collaboration with the state is the passport photo. No more than that. Just thoughts.

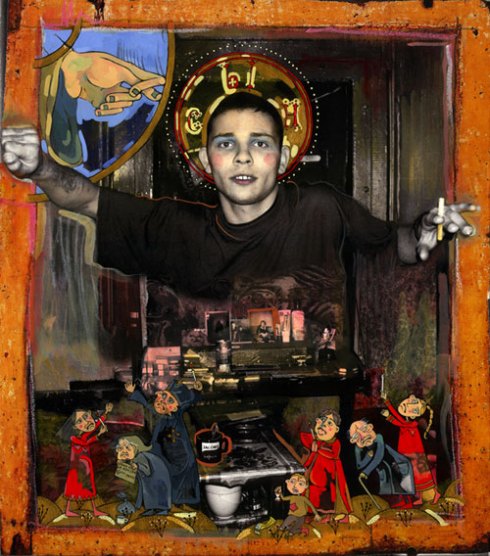

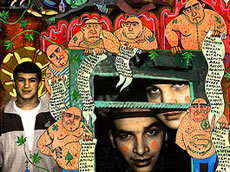

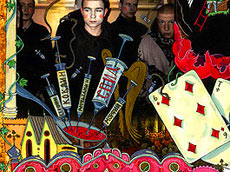

Yana Payusova’s Russian Prison Series is a complex portrait with embedded cultural memes and fierce visual détournement. It is a strong and committed project. Russian Prisons Series, painted photographs of forgotten incarcerated Russian youth is Payusova’s most extensive use of photography in her many series. In response to email request, Yana replied with the detailed account below.

PP: I am particularly interested in your experience within the prisons, your ability to photograph, your understanding with the boys & men in your images and your thoughts on photography and prisons generally.

I understand you joined your mother, who was working as a social worker, in Lebedeva and Kolpino prisons, St Petersburg. What were your initial reasons & motivations for working with the young men in these institutions?

YP: I first visited the Lebedeva prison in the fall of 2003. I was able to gain access to the prisons because my mother had been working with incarcerated teenagers there for the past nine years. She belonged (my mother has retired in 2007) to an organization called Rainbow of Hope. This organization initially specialized in working with street children, either homeless (orphans or abandoned children) or homeless by choice (those avoiding abusive situations at home). Street children are a brand new, post-perestroika phenomenon for Russia. Before the breakup of the USSR, unwanted and disabled children were housed in a Soviet-style orphanage system out of sight of society. However, there were also numerous social organizations, which created public programs for children, thus filling in where the family institution was lacking. Unfortunately, today, ragged, unwashed children hanging out in front of subway stations begging for money, smoking cigarettes and sniffing glue, are a common sight.

Rainbow of Hope formed a day-center where homeless children could eat, play, attend classes, and receive medical attention. Shortly after the inception of this new program, the social workers noticed that as some of ‘their’ kids matured they relapsed into their previous street behavior. They started disregarding any kind of authority; began consuming alcohol and hard drugs; getting in trouble for breaking into cars; and various small theft. Eventually, after either several minor offences or after one serious transgression, and if the kids were fourteen or older, they wound up in prison. When my mother first started visiting the prisons, she learned that in fact, many of the teenage inmates came from similar backgrounds: alcoholic parents (often single mothers), other incarcerated family members, chaotic upbringing without any positive adult supervision, childhood exposure to psychological and physical violence.

YP: I decided to accompany my mother in one of her weekly visits to the prisons. I cannot say that I was shocked the first time I entered one of these facilities. Having grown up in the Soviet Union and having seen royal palaces in extreme decay, I did not expect a vacation spa. The security guards were grim and humorless, the environment was filthy and unkept, and the barred-windowed buildings were rundown. There was a sense of complete surveillance, barbed wire and high brick fences always visible, a near complete blockage of the city’s activity beyond the walls. There was an eerie silence broken only by occasional savage barking of guard-dogs. The atmosphere was even more depressing once inside the prison building. The entire structure had an intolerable stale stench. It was later explained to us that this was the smell of lice being burned off the prisoners’ clothes. As we walked upstairs, we caught glimpses of the adult inmates. Their faces were gray and expressionless and they stood with their hands behind their backs.

YP: However, I was truly shocked when I saw the teenage convicts in person. When we arrived they were in their cells, mostly sleeping and passing time. They were brought out in front of us into the main hallway for lineup. I was expecting to see tough guys and intimidating criminal types, but instead I saw a group of scrawny, pale, shaven-headed young boys, many of whom were covered in warts and sores. I knew that all of them had to be ages 14 to 21, but the majority seemed like they could not be older than twelve (as I later learned, an indication of malnourishment in childhood). Many had tattooed limbs and torsos. A few of the tattoos were masterfully executed, but most were crude amateur drawings. Many of the tattoos were grossly infected. Ironically, the tattoo designs displayed harsh arrogance and aggression, which was markedly missing from most of the boys’ faces. Also, many of them spoke ‘blatnaya fenya’ (special cryptolanguage used among criminals) partially out of habit and partly to show off and flaunt their connections to the criminal culture.

PP: What did you discuss/teach each other?

YP: I was supposed to conduct an English class, however, we ended up simply talking in Russian. When they got over the initial cocky boy-talk and the showing-off in front of each other, we were able to enjoy a normal conversation. I was surprised to find out that for many, it was not their first time in prison. Paradoxically, many boys seemed to either enjoy or be ambivalent to being in prison. I got a sense that it was similar to belonging to a fraternity of sorts; with its own secret lingo and rituals. I knew that I wanted to learn more about this strange place, to find out why this hellish dump was so romanticized, while being so intolerable. It all seemed like such a paradox. I knew I wanted to come back to investigate.

PP: Exactly how long did you work there? How often did you visit?

YP: After my initial visit, I began volunteering at both Lebedeva prison (SIZO 47/4) and Kolpino colony (VK g. Kolpino) on a weekly basis. We usually visited the Lebedeva prison twice a week and the Kolpino colony on the weekend. In total, I spent around eight months visiting the prisons.

PP: At what point did you decide to take your camera into the prisons? I have read the prison staff made an exception for you and allowed you to shoot 5 rolls of film. Why was this? What sort of discussion/negotiation made this possible? What was the nature of your interactions with the young men? How much of the project did you explain to them?

YP: Two weeks before I left for the States, I was able to bring my camera inside the prison to take some pictures. I was only able to shoot five or six rolls because photographing inside the prison is prohibited, but the guards made an exception since I had worked there for an entire year. The boys were completely aware of me photographing them (in fact, I gave them copies of all of the images I shot). Since so many wanted to be photographed, the boys generally had only one chance to pose. Surprisingly, most were very relaxed and confidently confronted the camera.

PP: Had you even finalized the future use of your prints in your own mind at that time?

YP: While I was photographing the boys, I had no preconception of the future project.

After I developed the film, I felt dissatisfied with the images. The black and white portraits seemed so one-dimensional and flat, they did not even begin to scratch the surface of the complexity of my experience. The pictures captured the personality of a few individuals, but the images said nothing of history, character, or story. Similar to the way in which a prism expands plain white light into the entire color spectrum, I had to find a way to render these photographs; a way that would offer perspective and a unique angle; that would give me a vocabulary and a way to begin to speak about my experience.

When I began searching for a ‘prism’, it occurred to me that the entire experience working with the prisoners had a strong religious undertone. Most of the Rainbow of Hope’s sponsorship comes from Western missionary organizations (mostly from Southern states: Texas, Alabama). The raised and donated money is used to pay teachers to conduct classes in prisons, to buy hygiene products (such as soap, toothpaste and toothbrushes), celebrating the boys’ birthdays, buying medicine, socks, slippers and gloves in the winter, etc. However, all this comes with an additional non-monetary cost. Most missionary groups wish to see how their money is spent and like to personally visit the prisons. Since I am bi-lingual, I was to accompany such groups and serve as an interpreter during missionaries’ encounters with the prison’s residents.

YP: It was always mind-boggling for me to see how these foreigners could come into a country, knowing little about its culture and history, and speak with such aplomb about all of the country’s problems and offer their solutions. Naturally, most missionaries wanted to convert the sinful prisoners to Christianity and have them ‘invite Jesus into their hearts.’ While the boys were busy playing the roles of thieves and recidivists, the missionaries enacted their wild dreams of the great saviors, who could save an entire prison full of lost souls all before lunch. One day while translating the Jesus story for the fiftieth time, I began to ponder this concept of saints and sinners. While to the missionaries, the power dynamic was crystal clear, to me it was becoming progressively ambiguous.

As a starting point, I have decided to begin thinking about my experience using the religious terminology. Since the only official religion in Russia is (and has been for quite some time) Christian Orthodoxy, it seemed only natural to start my explorations there. Russia adopted the Byzantine form of Christianity (as in the Baptism of Kievan Rus’) in 988 A.D. As centuries passed, Christian Orthodoxy has penetrated every aspect of Russia’s social and cultural life; it is closely intertwined with its traditions and folklore. Even after seventy years in which the Soviet government actively had been trying to choke all aspects of spiritual life, most Russians will define themselves as Orthodox Christians. Although, for the majority, being a Christian, involves going to church twice a year for Christmas and Easter. In fact, most boys in prisons consider themselves to be Orthodox Christians and wear gold and silver crosses around their necks (sign that one has been baptized). Their tattoos involve quite a bit of religious iconography as well.

YP: I have always been fascinated by Orthodox icons. Beautiful objects hung on the wall, commanding such reverence, have always been mysterious to me because of their cryptic visual language. Similar to the obscure language of prison tattoos, the icons offered only glimpses into the rich exegesis of their symbolism and narrative. The individual symbols could be recognized (people, buildings, trees, animals), but when examined as a whole, lacked any coherent meaning. Originally the language of the icons was designed to be simple, its objective was accessibility to the illiterate and literate alike, but the clarity was lost as centuries passed. Conceptually, icons worked well with my idea; I wanted my work to speak of the boys’ experience while demonstrating my respect and compassion for their lives.

The word ‘icon,’ derived from the Greek ‘eikon,’ means an image, any image or representation, but in a stricter sense, it means a holy image to which special veneration is given. Unfortunately, the true intention for an icon to be an object only depicting that which is worshiped, is lost. Historically, the iconodules (the defenders or lovers of icons) had to come up with convincing formulations to prove that icons were not worshiped but venerated and that such veneration was not idolatry. Today, in a sense, the object itself became the thing that people worship, this is why I anticipated that the portrayal of prisoners in an iconic form may be offensive to some Orthodox Christians. I decided to proceed with my research and found myself getting ever more deeply fascinated by what I was finding.

It is curious that most representational formulas and compositions used in icon painting today have been established several centuries ago. One can compare an icon from the thirteenth century with one from the nineteenth century and notice virtually no major differences. There will be the exact same positioning of the figures, same gestures, and colors employed. Once one becomes aware of the grammar of the icon painting and learns the key characters of the stories, reading an icon becomes no different than reading a graphic novel or even a comic. This discovery enabled me to begin using the orthodox visual language in a post-modern form. Essentially, the iconographic structuralism of the church, gave me the means to create my own visual and cerebral language so that I could begin to analyze and interpret the complexity of the boys’ experience.

PP: Alex Sweetman has said. “She took this little world of prisons and looked through it to see the totality of Russian society – its corruption, its caste system, its misery.” How accurate a reflection is this of your position?

YP: In a country like the Soviet Union, where a significant part of the population (not necessarily criminals) went through labor camps, prison sub-cultures are very well developed and complex.

Not a very long time ago, it was considered shameful to admit to ever having been convicted or to having any family member in prison even though according to statistical study, one in four adult males in the former Soviet Union has been convicted at some point in time. Today, the criminal way of life is gaining wide acceptance and even gets glorified in the media. Countless movies and soap operas are produced about the glamorous lives of criminal ‘authorities’; they are endlessly written about in books; there is even an entire song genre of ‘blatnaya pesnya’ (criminal song) that exists. With the recent appearance of the infamous ‘New-Russian’ figure, having any relations to the mafia is considered cool, glamorous and prestigious. The New-Russian character has had a similar affect on Russian boys as Barbie has had on American girls. New-Russians are considered to be young (late twenties, early thirties), cool, loaded with cash, driving expensive cars, followed by henchmen doing all the dirty work, ex-criminals, sleep with attractive women, and have no one to answer to. They are appealing role models for young boys, many of whom lack any other alternative male role models in their lives. For many, prison functions as prep school for the criminal world. It offers a glimpse of a rigidly structured autonomous community where every member has their specially designated place and function. Some scholars argue that the rest of Russian society is modeled after the world of thieves and actually compare Kremlin principles and ideologies to those of a ‘pakhan’ (criminal authority) and his gang. If a government mimics such a model, what can be asked of teenage boys?

PP: What were/are the futures of the young men? Will some of them still be institutionalized? Will some be out?

YP: Some of the boys get out of prisons and move on with their lives. It obviously is easier if one has some kind of a support system (family, relatives). Many of the boys that I knew in prison have been to prison before and did not seem to think to be in some unfortunate predicament.

For many of the boys, who grew up neglected and unwanted, this situation is novel. For the first time in their lives, they had an opportunity to belong to a group with limited membership and clear sets of rules. As opposed to the chaos of street life, prison community offers established ground rules, protection, security, stability, a plan for the future, and most importantly, a family.

Unfortunately, with the current penitentiary system in place, these young fourteen-year-old boys become the perfect recruits for the criminal world. Generally, once detained, the teenagers are sent to pretrial detention (SIZO) prisons, either the Lebedeva SIZO or the infamous St. Petersburg’s “Kresty” prison. Both of these are adult facilities, where the minors are kept in a separate section of the floor, away from the adults. Both minors and adults are held in SIZO until they are tried in court. Until recently, the prisons have been so overcrowded that it was not uncommon that minors would have to wait up to three years to receive a court trial. Fortunately today (due to recent changes in jurisdiction), the majority waits approximately six to twelve months. Unfortunately, that still leaves plenty of time for any kind of peer pressure, physical violence, and rape, to take place. Therefore even a short time in prison can mark an individual for life.

YP: A prison stay also poses some very serious health threats. Russian prisons are infamous for epidemics of tuberculosis. Stale-aired, filthy, confined spaces hardly promote good health. According to GUIN’s (The Chief Directorate of Penitentiary Facilities) statistic, nearly one in ten convicts get infected with TB; many cases are fatal. The numbers for HIV-infected prisoners and prisoners suffering from AIDS are also extremely high. Lice, scabies, cockroaches, rats and other vermin are all the everyday reality of prison life.

However, prison must offer something unique in order to compensate for all of the dreadfulness. As complex as the prison sub-culture is, there are several key elements that are important to consider. One of the most important attributes of prison culture is its rigid hierarchy. Life in prisons is regulated by the unofficial ‘vorovskye zakony’ (thieves’ law), an oral collection of rules, norms and traditions for all ‘thieves’ to follow. Some of these laws date back to pre-revolutionary Russia. The majority, however, were formed during the GULAG years and have undergone many changes over time.

YP: For the young men with no family, prison becomes a place of acceptance and gives them a sense of purpose. Everyone aspires to become a ‘pakhan’ (criminal boss) and no one dreams of ever being an untouchable (lowest in prison hierarchy). Although the boys that I have met are far from resembling the macho superheroes they wish to be, many imitate the expected behavior. Many of the boys display a strong sense of camaraderie. I was immediately struck by an unusual display of affection among them as they constantly hang on to each other and wrap their arms around the others’ shoulders (some of that is evident in the photographs that I shot). Their community mirrors the hierarchy of an adult prison, although according to experts it is even more pronounced and cruel. Brutality and strength are the dominant forces. One is immediately able to discern the ‘bugri’ (alphas), the ‘blatnie’, and the untouchables. I was once speaking to a group of boys (8-10 people) who were all seated on a bench in front of me, when the two ‘bugri’ (alphas) came up to us. Without saying a word, all ten boys immediately got off the bench to let the ‘bugri’ sit. Apparently, the punishment for failing to show respect can be rather brutal.

Curiously, no matter how cruel the boys can be to one another, they show unusual kindness when it comes to kittens. It is not uncommon for each cell to have a pet kitten for which everyone gently cares. The cats breed inside the prison, catch rats, and have no problems moving between the bars. It was also interesting to see the ‘bugris’’ cells. The walls are covered with fake green vines, flowers, and stuffed animals (their girlfriends from the outside sent them). Hanging along side these niceties are posters depicting porn stars. Apparently, it is considered cool if one’s cell resembles a ‘normal’ room outside of prison.

PP: In a 2008 Boston Globe article said “you’d given up using photographs”. Explain that decision.

YP: I am not using photographic imagery in current projects, but it doesn’t mean that I will not do so in the future.

____________________________________________________

Yana’s CV is here. Yana won the juror’s prize at the 2005 CENTER Santa Fe awards. She is a member of the 6+ collective.

Massive thanks to Yana Payusova for her erudite, balanced and insightful words. It is a privilege for Prison Photography to host such a comprehensive account. Many, many thanks!

Please visit Yana’s website.

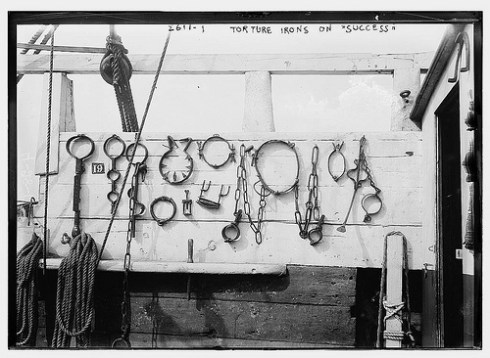

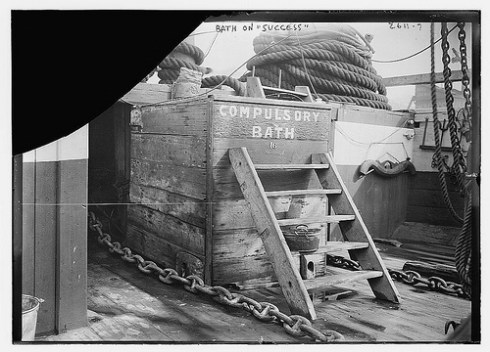

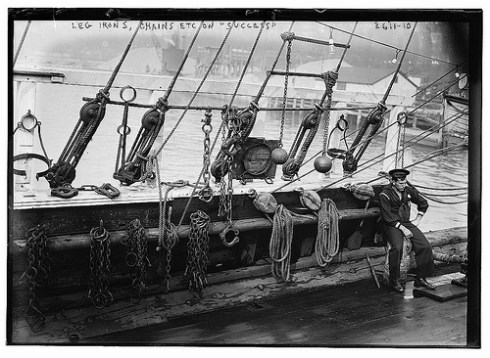

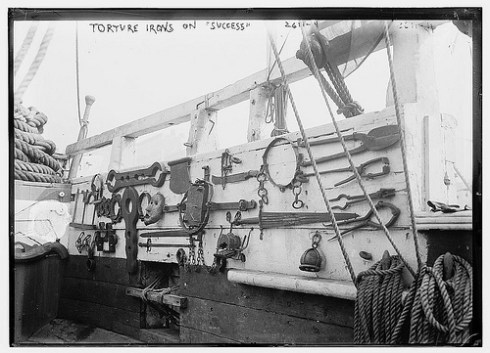

A couple of months ago, I wrote about the prison convict ship Success and its repurposing as a museum ship in the early 19th century. At that time, I featured a couple of images of the ship docked in Seattle and Tacoma. To continue from that visual anchor (pun intended), I’d like to share these few close up images of this unique and long-gone “Museum Ship of Colonial Horrors” (as I like to refer to it).

The accoutrements of abuse on display are chilling. The international seafaring exhibit was an old British and latterly Australian ship used for deportation of ‘criminals’ during Victorian times and for non-human commodities thereafter.

The accoutrements of abuse on display are chilling. The international seafaring exhibit was an old British and latterly Australian ship used for deportation of ‘criminals’ during Victorian times and for non-human commodities thereafter.

I wonder what sort of museological interpretation of Success was given to American audiences? Would this have been kept in a separate narrative to the slavery ships of the Atlantic or would all histories be foisted into one macabre reductive appreciation of the ‘Other’?

When I saw the iron jacket I was terrified, but then I read Wystan‘s description of the Wooden Maiden:

When I saw the iron jacket I was terrified, but then I read Wystan‘s description of the Wooden Maiden:

If you were very naughty, you might be asked to remove your clothing and climb inside this vertical coffin, where of course it was pitch dark, there was no water, and fresh air was scarce. Then the box (which was clad in sheet iron) would stand in the hot sun until you got nice and warm. But you wouldn’t want to slump or faint, because then your bare flesh might get snagged on the ends of the long nails that had been pounded into it from random directions . . .

All images from the Library of Congress on Flickr,

and searched out through Flickr Commons.

On Thursday, 28th May, photographs of prison conditions and detainee custody from six facilities other than Abu Ghraib will be released to the public.

Reports over the weekend suggested a figure of 44, but the Guardian has stated over 2,000 photographs are to be made public. Images of Bagram Air base in Afghanistan are included in the cache. Critics will surely scan for similarities in detention/torture methods used in Afghanistan as in Iraq to argue against the ‘few bad apples’ logic that railroaded earlier attempts to bring military and government commanding authorities to full-accountability.

ACLU’s advocacy deserves international acclaim. Not only have they forced the release of photographic evidence they won a ruling to prevent the destruction of audio tapes that record torture scenarios.

This is an interesting counterpoint. I presume we all assume we’ll see the images in the printed press. Would we expect the tapes to play on our televisions and radios? That scenario makes me uncomfortable.

Continuing with issues of format, it will be interesting to see how the media presents the-soon-to-be-released photographic documents in contrast to the recent torture memo’s. WoWoWoW set the bar low with the tabloid inquiry “How Bad Will They Be?” and the Los Angeles Times allays fears with a dead-pan assessment, “examined by Air Force and Army criminal investigators, are apparently not as shocking as those taken at Abu Ghraib.

No doubt these images will be contested and a ‘Meaning-War’ over the images will ensue, but I think people for and against the Bush administration’s interrogation policies are not going to change their position now – whatever the evidence.”

But, I guess it depends who’s looking.

Lefties want more weaponry in the push for prosecution of Bush and his cronies for war crimes. The right is debilitated and otherwise occupied by the economy, stocking guns before the “Obama-ban” and the latest Meghan McCain slur.

Politicians from both parties seem to want this to go away, snarking on about how the release of yet more Un-American activities will only fuel the burning hate toward the US. This position is an insult.

Did Bush care what Iraqi’s would think when he bombed them out of house and home? Did Bush care to think how American’s would react in the face of diminished civil liberties? Yet here, politicians of both parties are scrambling to avoid the negative reactions of entrenched, fundamental opponents INSTEAD of anticipating the beneficial good-will and return to mutual trust provided by honest disclosures of a transparent and constitutional government. Why cover-up a cover-up?

Maybe, the Democrats are shy to see these documents because they may implicate their top brass?

One concern I will air, is that all this could move toward some bizarre show-trial scenario, where lawyers bargain, Bush is spared, the American public settle for a conviction of Cheney, and careers and reputations lie in waste on both sides of the aisle!?!

I certainly didn’t expect the incriminating documents to flood as they have in recent weeks. I have no idea how all this is going to shake down. Obama doesn’t seem to have control of this. That doesn’t bother me. No-one can hold back the truth.

So, as wise at it’d be to remember the date, 28th May, you should bear in mind the photographs of abuse could well leak earlier…

________________________________________________

First Image lifted from Gerry May. http://www.gerrymay.com/?p=1426

Cartoon courtesy of the Nation. http://www.thenation.com/doc/20050307/duzyj

Final Image by Takomabibelot. http://www.flickr.com/photos/takomabibelot/2090273618/

© Stephan Sahm, from the series 'My Cage is My Castle'

It takes something special to jolt me from my ‘prison-photo-myopia’.

The European Prize of Architectural Photography has the most cohesive group of fine art photography winners and honorable mentions I’ve seen in the past five years. The theme was “New Homeland”. Each photographer has four prints as representative works and each mini-set is a treat!

Outstanding quality.

© Jacky Longstaff

You can browse the links provided below, but first see the 2009 Prize Winners Gallery.

Photographers formally recognised are Stephan Sahm, Tim Griffith, Jacky Longstaff, Freudenberger & Bachmeier, Kai-Uwe Gundlach, Frank Meyl, Szymon Necki, Menno Aden, Johanna Ahlert, Nicolas Briffod, Judith Buss, Walter Fogel, Andreas Fragel, Matthieu Gafsou, Benjamin Gerull, Juri Gottschall, Hanna Kohl, Shimizu Ken, Meike Hansen, Jonas Holthaus, Werner Huthmacher, Christian Kain, Sally-Ann Norman, Florian Profitlich, Andrew Phelps, Martin Richter, Martin Roemers, Michael Schnabel, Marcus Schwier, Michael van den Bogaard.

I was only aware of Fragel, Gafsou and Phelps previously.

© Frank Meyl

© Matthieu Gafsou

© Marcus Schwier

© Kal Uwe Gundlach

I suppose if I were to push for a relation of any of these works to ‘Photography Within Sites of Incarceration’ I would want to begin a dialogue on Sahm’s Hamster-Pop representations of confinement. Sahm was the grand prize winner.

With Jurgen Chill winning two years ago, and the presumed associations of borders and immigration within the theme of “New Homeland”, the European Prize of Architectural Photography apparently rewards photography that emphasises the psychological impact of architectural forms on its users/subjects – in which, notions of containment and non-containment are central.

________________________________________________________

I am aware Prison Photography has been preoccupied with fine art depictions of prison space recently and I intend to redress this genre imbalance in the coming weeks with more documentary works.

Coverage of aging prison populations will receive more column inches, online commentary, pixels and pingbacks in the coming years. Just as social security needs overhaul in the US and the pension age is to be raised in the UK, so too new means of fiscal policy are needed to cater for the elderly behind bars … on both sides of the pond.

Edmund Clark’s Still Life: Killing Time is a quiet meditation on the slowness, the fabric and the accoutrements of prison life for elderly inmates. It was two years in the making. This was a hard project to track down. It seems all of Edmund Clark’s promotion is done by others; by publishers, journos, gallerists and supporters. Clark has no website. Clark is as inconspicuous as his subjects.

Clark doesn’t do the commentary for the Guardian‘s Audio Slideshow (MUST SEE). In his absence, Erwin James does a great job of whispering the tragic, hard realities of the prison environment. I include and italicise Erwin’s comments below Clark’s photographs.

“It saddens me when I see these pictures, these tokens of disablement, the accoutrements of disability; a chair lift, a walking stick, a walking frame. I think that is when I struggle with the idea that these people should be in prison. If someone is demonstrably infirm, demonstrably not functioning well through age or ill health, a prison environment (which this clearly is) is not the appropriate environment.”

It’s worth noting some background to the series. Elderly prison populations only recently became serious noticeable enough for HM Prison Service to trial different modes of containment. The E-Wing of Kingston Prison, Portsmouth was the first experiment. In 2007, upon publication of the book, Erwin James explained;

The answer was Kingston’s E wing. For eight years, this was home to up to 25 elderly men serving life for murder, rape, child sex offences and other offences of violence. The men were aged from their late 50s to over 80. Many had been in prison for more than 10 years, and several for stretches of 30 years or more. E wing as a special facility for elderly prisoners no longer exists. The only other wing dedicated to infirm and disabled prisoners now is in Norwich prison, Norfolk.

“I think cell bars are a tough one. They offer a difficult vista. When you look through cell bars you are aware that the outside doesn’t belong to you. You’re disengaged. And when you see cell bars with a bit of colour like that – the flower and the card – it’s a bit incongruous. These old guys are still humans.”

But for James, as for myself, and particularly for Clark, this is not about sympathy or compassion for the convicted criminal. It has already been stated that these men are serious criminals. There surely must come a point though when an old man is not the physical threat he once was. Simon Norfolk – a photographer I personally consider one of Britain’s best – wrote for the foreword;

” … why are there bars on the window of a man who can’t walk without a frame. What kind of escape plan can be hatched by a man who can’t remember how to go to the toilet.”

“This picture for me epitomizes the absurdity, and moments of madness the prison system can have. We are keeping someone in prison, who has dementia. They have basic instruction about how to go to the toilet. If there were ever a case for somebody who needs not to be in prison, it would be for that person.”

The only statement I can find directly from Clark, the photographer, is worth meditation.

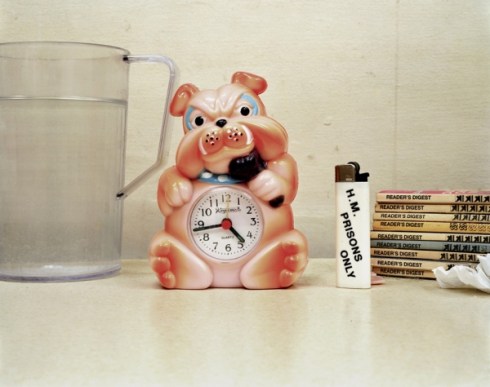

What you can see in the pictures is to what extent they are engaged with their routine, and on top of their regime and what sort of engagement they have with time. One man, who wore a long grey beard, coped with the passage of time, as far as I could see, by disengaging with it completely. He spent most of his time sitting in his chair … He just sat and disappeared within himself. After about a year I could go and talk to him, and this man was clever, he’d been a captain in the merchant navy and had sailed around the world. I asked him once what was the best place he’d been to and he lifted his head and said, ‘Sao Paulo, I loved Brazil …’ And then suddenly this life came out, his life was all there, hidden away. The bulldog clock on the book cover belonged to him, it was one of his prized possessions.

Apparently, Clark created this body of work spurred by reports from the USA about mandatory sentencing under “Three Strikes Laws” and the consequent swelling of America’s prison population. Clark engaged with Britain’s aging prison population in direct response to demographic disasters in American penal policy. Clark elaborates;

People subjected to it [Three Strikes Law] were swelling the ranks of the prison population, with the result that many men sentenced when young would spend the rest of their lives incarcerated. I wondered what the response in the UK was to those incarcerated for many years – the life prisoners, or ‘lifers’, who face an old age and growing infirmity in an institutional environment still ruled by the survival of the fittest.

Clark made his point by seeking out the UK’s first specialised prison facility for aged prisoners and then produced a body of work that is distinctly British. Photographs of Bond posters, a (British?) Bulldog, Red-top clippings of Diana & the Queen, and framed artwork of common birds to British gardens & allotments; these are not obvious clues to a global appreciation of prison culture. I conclude, Clark thinks globally, acts locally.

“If you are young and strong prison is manageable on the whole. If you feel weak or infirm or poorly it is a harder place to be and these photographs epitomize the frailty factor, the danger of getting old in prison or being old in prison … My feeling about prison is that it is not a place for old people. Prison is one environment for everybody regardless of your circumstances and so what happens is your survival depends on luck and natural resources. And if you’re old you’re not gonna have as much luck as the younger guys.”

“There’s a lot of people in the system who know that prison is not a place for old, infirm, disabled people. And its not. I’m not saying that they shouldn’t be separated from society, but I am talking about prison as we know it. The common interpretation of prison is landings, wings, cells, prison officers, dogs, security; that whole encapsulation of captivity. If you are infirm there needs to be another place. We are giving extra punishment to the weak people.”

“There is an argument for separating the old folks from the main prison wing and that is what happened here. It was an experiment. E-Wing. The danger for me is that is becomes a place … you know, they talked of the fetid atmosphere; smelly and hot. The smell of old people. As a society we don’t have a lot of respect for old people.”

Clark’s unambiguous images of mobile aids and instructions for the senile are a clear call for change. His studies of prized-possessions and personal ordering of objects play on emotional responses to depicted vulnerabilities; Clark’s works conspire as a whole (43 images in total) to shape a convincing argument that we should all care about how our prison system accommodates different demographics. The elderly demographic is only growing, only advancing … with time.

As James’ words have served me so well throughout this article I shall close with his take on public opinion.

“I am pleased society is taking this on, because prison is a robust and hostile environment, and in fact the authorities refer to all prisons as hostile environments. That’s how they’re officially termed. That’s not because everyone who goes there are dangerous, but I think prison brings out the worst in a lot of people. It can bring out the best, but often it brings out the worst. And that’s not to say they are bad characters, it’s because people in prison are defensive and they are defensive because they are frightened.”

__________________________________________________________

All images copyright of Edmund Clark.

Still Life: Killing Time, by Edmund Clark, is published by Dewi Lewis, and avaiable at PhotoEye

Images Unseen, Images Unknown written by a guest blogger on Prison Photography last week was well received by readers, provoking more questions and some intriguing possibilities.

Change.org offered a synopsis of the article. Change.org focused on the concluding points of Images Unseen, Images Unknown which described the culture of shame shrouding California prisons created by the control of images and manipulated invisibility.

Too many prisoners are hidden from view to serve out their time. Many prisoners refuse visits from family because they don’t want loved ones to see them in institutions that deny them individuality, work to subdue the general population, hide prisoners from society, and keep them docile.

So, the issue of self-representation and empowerment arises. Specific to my interest would be the possibilities of empowerment through photography.

Recently, Stan Banos asked me, “Are you aware of any photography programs in prison for prisoners.”

My answer, in short, is no. This doesn’t mean they don’t exist, it just means for all my searching I have unearthed nothing.

Art therapy has been explored among prison populations and recently San Quentin piloted it’s first ever ‘Film School’. The project did many things at once, teaching inmates the technical skills of documentary film making, building team work and trust; and it allowed inmates to communicate narratives of their choosing from prison life.

Inmates documented the work of the prison nurses distributing medications; filmed the prison kitchens; recorded the “wasted talent” of artists, musicians and writers within San Quentin; and studied American Islamic faith in prison.

With that in mind, we can say empowerment through the arts has been well explored and apparently successful in a number of penal institutions. However, it would seem photography in prisons has not been used as a tool for self-representation and rehabilitation … yet.

Turn Away © Stephene Brathwaite, Red Hook Community Justice Center Photo Project

The model for this type of program exists. Dozens of important non-profits use photography as a means for at-risk-youth to tell their stories. Organisations such as Youth in Focus, Seattle; AS220 Youth Photography Program, Providence, RI: Focus on Youth, Portland; New Urban Arts, Providence; Critical Exposure, Washington DC; First Exposures by SF Camerawork in San Francisco; The In-Sight Photography Project, Vermont; Leave Out ViolencE (LOVE), Nova Scotia; Inner City Light, Chicago; My Story, Portland, OR; Picture Me at the MoCP, Chicago; and Eye on the Third Ward, Houston; The Bridge, Charlottesville, VA; and Emily Schiffer’s My Viewpoint Photo Initiative are exemplars of empowerment through photography.

The Red Hook Photo Project New York offers photography opportunities specifically to a community blighted by crime. The photo project is run by the Red Hook Community Justice Center which operates many programs to improve the lives of teens within the geographically and socially isolated Red Hook Neighbourhood.

Only slight tweaks would be necessary to these types of programs for them to be effective as rehabilitative tools among prison populations. The central driving philosophy is to offer individuals a method of self-representation they’ve never been afforded previously.

A Backwards Eye © Gwendolyn Reed, Red Hook Community Justice Center Photo Project

It seems the main factor, aside of funding, for rehabilitative programs establishing themselves in prisons, is the philosophy of individual wardens. San Quentin Film School was pitched repeatedly across 47 states until Warden Robert Ayers decided to launch it at San Quentin. Likewise Burl Cain, at Louisiana State Penitentiary (Angola) has become well known for maintaining a varied roster of programs to keep inmates occupied. They include the renowned (and ethically questionable) Rodeo, an American Football league and a hospice program in which inmates volunteer to carry out the palliative care tasks.

On this evidence, it would make sense that criminal justice reformers and those interested in increasing the visibility of prisons should actively seek out wardens currently supporting novel, or even pilot, projects. Wardens currently accommodate programs in education, the arts, dog-training, first aid, video and much more. Photography could be added to that list.

There is a lot of mainstream media programs featuring American prisons – Lockdown, Americas Hardest Prisons, Inside American Jail – but of course these are all made for cable distribution and ultimately profit; their common denominator is a heightened sensationalism.

© Wayman, Inner City Light Student Photography Project

Documentary projects upholding rehabilitation and education as their core purpose are a distinctively different type of exposure. There would be no need for regional or national television channels to provide financial backing as an end (marketable) product would not be the motivation. That said, if the narratives of such documentary projects could be shown to enhance the image of an institution the prison authority might be open to trying them. The prison warden has the decision making power, so if under a wardens leadership a prison is given (positive) exposure it makes sense that the warden would be interested.

All successful rehabilitative arts programs presumably share a cooperative approach from the outset. Wardens and authorities are not to be feared or misunderstood, but can be convinced, cajoled and open to novel suggestions and programs.

Matt Kelley has suggested that the criminal justice reform community take note of wardens who are open to more transparency within their institution. Could coordinated media access drive a movement against the “invisibility” of prisons in America today?

The ideal program I envisage, would have only a small operating budget allowing pre-screened inmates to learn the practical skills of photography and apply them for the purposes of self representation.

If San Quentin can mount a film school I am sure any prison in the future can develop a Photography School? What do you think?

I Reach © Stephene Brathwaite, Red Hook Community Justice Center Photo Project

It gives me great pleasure to introduce Prison Photography‘s first guest blogger. However, it saddens me as much that he must remain anonymous.

A couple of months ago, I received an email from a California state employee who worked as a prison educator. To paraphrase that initial contact, he stated that “California prisons were places of extreme emotion and stress – due in part to their ‘invisibility’ – and photography within the walls of prisons could go some way in bringing visibility and public understanding to the realities of contemporary prisons.” This was a remarkable statement and the first of its kind that I had heard from someone in employment at a state prison. I asked if he could expand on those thoughts and I am grateful he did.

The great irony of this is that the essay is not illustrated by the images he witnesses daily. He has offered us poignant descriptions of scenes from within prison. The descriptions are a powerful device to get us thinking about what we think we know and what we potentially could know about our penal system.

He suggested I use some of CDCR’s own images. The aerial shots included are the official vision of the California prison system that disciplines and orders the different sized units that comprise the institution; cells, wings, blocks and facilities. The institutional eye of CDCR’s aerial views lies in powerful contrast to the personal narrative recorded here.

Avenal State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

I work in California prisons. Penology has become grown into avocation over the last 10 years. A past career in journalism with some practice in photojournalism informs a strong inclination to report/communicate what I see and experience. So I am daily frustrated by prison policies against recording the visual images I see. Each day I wonder if these policies are justified. If not, are they an impediment to rehabilitation, perhaps even prison reform? Do these policies protect society and the prisoners and staff persons who are a part of society? Or are these policies so much heavy furniture upon the carpeting under which we have swept our societal human detritus?

[IMAGE] There but for the grace of God go I – Close up of a hollow expression on the face of a prisoner as he watches two uniformed guards escort another prisoner across the bare, brown dirt of a prison yard. One guard holds a baton at the ready, the other menacingly waves a carafe-sized container of pepper spray, his finger on the trigger. In the background are multiple 12-foot chain-link faces topped by rounds of glistening razor wire.

North Kern State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

If you ever work with law enforcement on the street, you will hear the mantra “officer safety.” Policies, procedures, even individual officer actions have this mantra as an underlying core within their stated mission to serve public safety. In the prison, that mantra becomes “safety and security of the institution.” Everything is measured against that mantra. Nothing is approved if anyone can show that it may be a threat to institutional safety and/or security. Uncensored and uncontrolled photographic images seem to be considered an inherent threat to institutional safety and security. From a rookie guard to the departmental secretary, few things seem to frighten them quite so much as image impotence in the institutions they so wholly control. From regular staff trainings to informal reminders I have been inculcated (brainwashed?) to accept the imprudence of taking pictures on prison grounds. Simply having a camera on prison property could be cause for termination.

[IMAGE] The burden of laundry – a prisoner wearing only boxer shorts sits on the lowest metal slab of a three-high tier of bunk beds in a prison gymnasium. His hands are deep in a bright yellow, worn mop bucket on the floor in front of him. Inside, white socks and underwear mingle in lukewarm, soapy water.

Prison regulations acknowledge their public nature and the public’s right to know what goes on inside prisons, at least bureaucratically. Title 15 of California Code of Regulations, Section3260 is entitled “Public Access to Facilities and Programs.” It states:

“Correctional facilities and programs are operated at public expense for the protection of society. The public has a right and a duty to know how such facilities and programs are being conducted. It is the policy of the department to make known to the public, through the news media, through contact with public groups and individuals, and by making its public records available for review by interested persons, all relevant information pertaining to operations of the department and facilities. However, due consideration will be given to all factors which might threaten the safety of the facility in any way, or unnecessarily intrude upon the personal privacy of inmates and staff. The public must be given a true and accurate picture of department institutions and parole operations.”

Is absolute control over visual images in and around prison an unreasonable imposition on prisoners, staff, families, general public, media, etc? Does it interfere with the desirable goal of family/community connection with prisoners? Does it contribute anything to either rehabilitation or punishment, the two general goals of incarceration? I’ve catalogued the reasons I’ve been given, or even imagined, over the years and want to see how they stand up to public scrutiny.

Pleasant Valley State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

The first and foremost reason for image control would seem to be the prevention of both escapes and incursions. Photographs of prisons may provide intelligence to anyone planning escapes, contraband smuggling, perhaps even terrorist activities. This seems reasonable enough, at least until you start prowling around the Internet. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Web site has high-resolution aerial photographs of every one of its prisons. Anyone with even rudimentary analysis skills could do serious escape/incursion planning based on these photographs alone. But wait, there’s more. Google maps have more information – local maps, photographs of the prisons, even their “street view” photographs in some instances that clearly show fences, towers, gates, etc. With that level of public information available, I don’t see how you make a credible argument that I can’t take pictures on prison grounds.

5th & Western, Norco, CA. Google Street View.

[IMAGE] The spread – four heavily tattooed prisoners in underwear standing around a dented, dingy gray metal locker. There are bowls on top of the locker and they are sharing food they cooked using hot water, instant soup noodle packets and canned meats, vegetables and seasonings. On the dirty gray concrete wall behind them is stenciled in fading red paint: NO WARNING SHOTS FIRED.

Privacy would seem to be the next strongest argument for prohibiting prison images. Given the open policies in other states, this argument seems flimsy. For prisoners, all conviction information is public. Simply go to the appropriate county court and the information is openly available to the public. Yet it is extremely difficult to get any information about prisoners in the California prisons. For the public there is one telephone number you can call. [916 445-6713] You must know either the prisoner’s CDCR Identification Number or the full name and correct date of birth. The line is perpetually busy and, if answered, the caller can expect to be put on hold for a long, long time (yes, hours). On the other hand, if you go to the Nevada Department of Corrections Web site, you can search for Orenthal Simpson and it will show not only his prison and address but all his convicted offenses, terms and release date. Oklahoma, not generally known for openness, shows the prisoner’s location, convicted offenses, release and parole dates, even pictures. The federal Bureau of Prisons will provide prisoner location and release dates for current and past prisoners. Try a search on their site for Martha Stewart.

Salinas Valley State Prison. Courtesy CDCR

A major defense California prison management will make for the privacy argument is gang violence. They believe if it is easy to find a person in a particular prison, that can make it easier for gangs to use him. The gangs may use the prisoner to do their illegal work or to order him killed if he has fallen from grace, so to speak. CDCR logic is that by keeping prisoners hidden they are keeping them protected. If this is true, the magnitude of the gang problem is nothing short of monumental. Other states apparently do not have this problem. Why not?

[IMAGE] A pile of clothing, denim pants, orange coveralls, boots, etc. on a six-foot folding table. Two uniformed guards on one side of the table. Two naked inmates on the other side of the table, one bent over spreading his rear-end cheeks for officer inspection.

I categorize all other arguments against my taking prison pictures as simple totalitarian need for control. An uncontrolled image is seen as a risk – and why take a risk? The fewer images that exist, the fewer possibilities there are for something to happen that they can’t control. Statistically speaking, very few members of the public or the media ever get to see what happens inside prisons. Media representatives are escorted at all times and only see what prison management wants them to see. They are rarely given unfettered access to prisoners. Visitors are the bulk of the public that see anything of a prison, and that is a very limited view – parking lots, processing rooms and the visiting rooms. Even inmate appearance is tightly controlled in the visiting experience. The prisoner who shows up needing a shave or wearing a wrinkled shirt doesn’t get into the visiting room. And he or she will be strip-searched going in and coming out.

San Quentin. Courtesy CDCR

Prisons, at least in California, are reactive rather than proactive. California’s first permanent prison, San Quentin, opened for business in 1852. Since then, the prison system has been making rules and regulations based on preventing the recurrence of negative events. For example, a prisoner at R.J. Donovan prison at San Diego escaped using a fake staff identification card he had made. He walked out amid a small crowd of other staff leaving at shift change time. As was customary then, he simply held up his photo ID and was waved through with the rest of the ID card wavers. To prevent this from happening again, CDCR policy now requires the gate officer to physically touch and examine the employee ID card before letting the person through the gate. Such policy-creation has been repeated tens of thousands of times over the past 157 years of the California state prison system. It does not lend itself to the openness of unfettered prison images.

[IMAGE] The back of a prisoner’s shaved head as he sits in the audience of a GED graduation ceremony. Visible under his mortarboard are gang tattoos on his head and neck. Blurred in the background an inmate stands at the podium giving his valedictory address.

Until 1980, incarceration in California had rehabilitation as a major goal. The state legislature in that year, bowing to a Reganesque rabble-rousing changed prison law to say the purpose of incarceration is punishment. The concept of rehabilitation disappeared and so did most of the prisoner programming and policies meant to promote rehabilitation. Connection with family is known to be one of the most important factors in rehabilitation. I suggest the control of images in the prison system is one policy that discourages family connections.

Substance Abuse Treatment Facility at Corcoran. Courtesy CDCR

Prison subsumes human beings. Prisoners disappear over time. As soon as a man goes to prison, he begins to fade from his former life. Just as a photographic print will fade over the years, the place of a man in his family fades while he is in prison. Life goes on – without him. His linkages to the fabric of family and community eventually fray and break. Phone calls, letters and visits cannot fully replace the foundations of shared daily interactions, family projects, adventures, challenges and the intimacy of shared emotions. Despite our ability to love, we are creatures of habit, and over time absence can become a habit that seems a normal reality.

The absence of prison images in society supports the concept of shame in incarceration. This shame then supports an estrangement that prison system managers find useful for their purposes. The human toll of that is prisoners who simply hunker down to do their time. Some resist family contact. “I don’t want my children coming to see me in a place like this,” is a common thing I hear from prisoners who could have visits if they wanted them. Would this change if prison images were common in our society? I think so. I think it’s worth a try.