You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison’ tag.

98 prisoners are kept in a cell measuring 25 square meters originally designed for 16 inmates. The longest-serving prisoner in one of these cells has been there for 5 years. The prisoners are locked up for crimes as varied as non-payment of alimony to murder. The long-timers sleep in hammocks up high, the newcomers on the floor. Temperatures reach 50 degrees celsius in the summer. The prisoners are the poorest members of society, have poor legal representation, and are disenfranchised from political representation as they have no vote.

Gary Knight, Private Photo Review

Overcrowding at Polinter pre-trail detention centre, Rio de Janeiro © Gary Knight, VII Agency

Originally published in Social Issues #42 last Autumn, Gary Knight‘s astonishing photography at one of the (now closed) overcrowded Polinter Prisons in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Polinters are temporary holding facilities used to house police detainees.

There’s a bit of back story in to Knight’s work in his interview with the Financial Times.

Two things intrigue me about this. Firstly, my research tells me this prison closed down late 2006/early 2007. Why has it taken so long for Knight’s photography to get even short coverage? Secondly, I am astounded by Knight’s answer to the question of how he secured access:

I was doing a project on poverty, and a photographer at O Globo newspaper in Rio introduced me to the governor of Polinter prison – a place with conditions so bad the governor herself was appalled. She wanted something to be done but she couldn’t really let in a photographer from a local paper. She felt more comfortable with a foreigner: I guess she thought that stories published overseas might put pressure on the government from abroad.

Can you imagine a reversal of this logic? That US prison wardens would accommodate foreign photojournalists more readily?

Knight does his part in bringing visibility to the situation, but that doesn’t affect the shut out experienced by local photographers. That said, it is a great example of the power of international photojournalist activity bringing new possibilities to bear.

Detailed information on the Polinter prisons is hard to come by. We should share Knight’s relief that the Polinter he photographed is now closed. Amnesty International mentioned it in its 2006 report on Brazil:

In Rio de Janeiro, human rights groups denounced conditions in the Polinter pre-trial detention centre. In August the unit held 1,500 detainees in a space designed for 250, with an average of 90 men per 3m x 4m cell. Between January and June, three men were killed in incidents between prisoners. Officials in the detention centre were also forcing detainees to choose which criminal faction they wished to be segregated with inside Polinter. In November the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ordered the Brazilian government to take measures to improve the situation.

Finally, let’s consider with necessary dexterity the role that Pastor Marcos Pereira da Silva plays in all of this. He visits, evangelises, “foot-stomps”, exorcises evil and sends prisoners collapsing to the floor. Knight confesses a “real disquiet about him”. Supporters point to the fact that violence in Polinter has abated since da Silva’s visits, but Knight parries that its easy to influence the most vulnerable of groups.

I cannot bring myself to embed the video of the Pastor at work, but you can follow this link and thusly imagine him bouncing around the walls of a prison, agitating its population and putting on a show they’re not likely to witness again or even understand. I guess different eyes experience different wonder.

_______________________________________________________

UPDATE (06.01.2012): The Open Society Institute published Justice Denied: Brazil’s Polinters, documentary video focusing on “the costs of excessive and unnecessary pretrial detention.”

The poor conditions are obvious. OSI describes the film as part of their broader work on “a Global Campaign for Pretrial Justice […] helping governments develop bail and supervision systems that can make pretrial detention an exception, and not the rule.”

_______________________________________________________

Gary Knight, born in England, started working as a photographer in Southeast Asia during the 1980s as Indochina emerged from bitter wars and the region came to grips with the end of Cold War. In 1993, he moved to collapsing Yugoslavia where he returned repeatedly from the siege of Sarajevo through the fall of Kosovo. Between assignments for Newsweek, he documented crimes against humanity.

After 9/11, he worked in Afghanistan and two years later independently followed U.S. troops into Iraq. He covered wars in the Middle East, Africa, Europe and Asia and other breaking news, but Knight’s central focus is on the survival of the world’s poor and fundamental human rights issues.

Knight is founding director of VII Photo Agency. He established the Angkor Photo Festival, is a board member of the Crimes of War Foundation, a trustee of the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation and Vice President of the Pierre & Alexandra Boulat Foundation.

His work, widely awarded, published in magazines, is in museums and private collections. He has initiated education programs with universities and voluntary agencies, and is the author of Evidence: War Crimes in Kosovo.

If you are going to spend time with anything though, make it dispatches, a superbly edited magazine co-founded by Kinght. It cuts to the core of the issues, the rest of us skirt from distance.

(Found via Travel Photographer)

Images Unseen, Images Unknown written by a guest blogger on Prison Photography last week was well received by readers, provoking more questions and some intriguing possibilities.

Change.org offered a synopsis of the article. Change.org focused on the concluding points of Images Unseen, Images Unknown which described the culture of shame shrouding California prisons created by the control of images and manipulated invisibility.

Too many prisoners are hidden from view to serve out their time. Many prisoners refuse visits from family because they don’t want loved ones to see them in institutions that deny them individuality, work to subdue the general population, hide prisoners from society, and keep them docile.

So, the issue of self-representation and empowerment arises. Specific to my interest would be the possibilities of empowerment through photography.

Recently, Stan Banos asked me, “Are you aware of any photography programs in prison for prisoners.”

My answer, in short, is no. This doesn’t mean they don’t exist, it just means for all my searching I have unearthed nothing.

Art therapy has been explored among prison populations and recently San Quentin piloted it’s first ever ‘Film School’. The project did many things at once, teaching inmates the technical skills of documentary film making, building team work and trust; and it allowed inmates to communicate narratives of their choosing from prison life.

Inmates documented the work of the prison nurses distributing medications; filmed the prison kitchens; recorded the “wasted talent” of artists, musicians and writers within San Quentin; and studied American Islamic faith in prison.

With that in mind, we can say empowerment through the arts has been well explored and apparently successful in a number of penal institutions. However, it would seem photography in prisons has not been used as a tool for self-representation and rehabilitation … yet.

Turn Away © Stephene Brathwaite, Red Hook Community Justice Center Photo Project

The model for this type of program exists. Dozens of important non-profits use photography as a means for at-risk-youth to tell their stories. Organisations such as Youth in Focus, Seattle; AS220 Youth Photography Program, Providence, RI: Focus on Youth, Portland; New Urban Arts, Providence; Critical Exposure, Washington DC; First Exposures by SF Camerawork in San Francisco; The In-Sight Photography Project, Vermont; Leave Out ViolencE (LOVE), Nova Scotia; Inner City Light, Chicago; My Story, Portland, OR; Picture Me at the MoCP, Chicago; and Eye on the Third Ward, Houston; The Bridge, Charlottesville, VA; and Emily Schiffer’s My Viewpoint Photo Initiative are exemplars of empowerment through photography.

The Red Hook Photo Project New York offers photography opportunities specifically to a community blighted by crime. The photo project is run by the Red Hook Community Justice Center which operates many programs to improve the lives of teens within the geographically and socially isolated Red Hook Neighbourhood.

Only slight tweaks would be necessary to these types of programs for them to be effective as rehabilitative tools among prison populations. The central driving philosophy is to offer individuals a method of self-representation they’ve never been afforded previously.

A Backwards Eye © Gwendolyn Reed, Red Hook Community Justice Center Photo Project

It seems the main factor, aside of funding, for rehabilitative programs establishing themselves in prisons, is the philosophy of individual wardens. San Quentin Film School was pitched repeatedly across 47 states until Warden Robert Ayers decided to launch it at San Quentin. Likewise Burl Cain, at Louisiana State Penitentiary (Angola) has become well known for maintaining a varied roster of programs to keep inmates occupied. They include the renowned (and ethically questionable) Rodeo, an American Football league and a hospice program in which inmates volunteer to carry out the palliative care tasks.

On this evidence, it would make sense that criminal justice reformers and those interested in increasing the visibility of prisons should actively seek out wardens currently supporting novel, or even pilot, projects. Wardens currently accommodate programs in education, the arts, dog-training, first aid, video and much more. Photography could be added to that list.

There is a lot of mainstream media programs featuring American prisons – Lockdown, Americas Hardest Prisons, Inside American Jail – but of course these are all made for cable distribution and ultimately profit; their common denominator is a heightened sensationalism.

© Wayman, Inner City Light Student Photography Project

Documentary projects upholding rehabilitation and education as their core purpose are a distinctively different type of exposure. There would be no need for regional or national television channels to provide financial backing as an end (marketable) product would not be the motivation. That said, if the narratives of such documentary projects could be shown to enhance the image of an institution the prison authority might be open to trying them. The prison warden has the decision making power, so if under a wardens leadership a prison is given (positive) exposure it makes sense that the warden would be interested.

All successful rehabilitative arts programs presumably share a cooperative approach from the outset. Wardens and authorities are not to be feared or misunderstood, but can be convinced, cajoled and open to novel suggestions and programs.

Matt Kelley has suggested that the criminal justice reform community take note of wardens who are open to more transparency within their institution. Could coordinated media access drive a movement against the “invisibility” of prisons in America today?

The ideal program I envisage, would have only a small operating budget allowing pre-screened inmates to learn the practical skills of photography and apply them for the purposes of self representation.

If San Quentin can mount a film school I am sure any prison in the future can develop a Photography School? What do you think?

I Reach © Stephene Brathwaite, Red Hook Community Justice Center Photo Project

If an individual and the law don’t agree to the point the individual is imprisoned, one hopes lawful imprisonment changes the individual, right? For the better, right?

Unfortunately, American prisons have proved the opposite of rehabilitative or hopeful of positive change. Recidivism rates in America are between 60% and 68% (depending on the source).

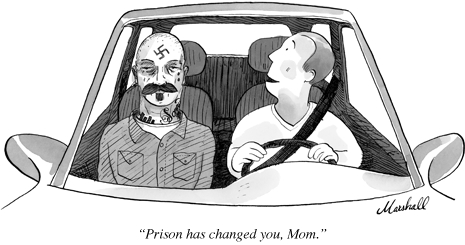

"Prison has changed you, Mom" © 2009 Marshall for the New Yorker

Spurred possibly by the fiscal-driven prisoner releases across the nation, Marshall penciled this pearl.

Some of the best comedy is simultaneously tragedy. The truth is America’s prison archipelago has bruised the lives of the current 2.2 million prison population, the lives of family members AND our lives and communities. Inmates returning to society haven’t been suitably prepared or shown new paths. Change has been for the worse in majority of cases.

I was astonished to read this AlertNet article. It excavates the background to Lovelle Mixon’s massacre in Oakland that killed four people.

I cannot agree with the article’s logic 100%. It would be a sad day if I ever presumed the individual totally powerless and unable to act upon non-violent decisions, but as the author writes:

“Though Mixon’s killing spree is a horrible aberration, his plight as an unemployed ex-felon isn’t. There are tens of thousands like him on America’s streets. In 2007, the National Institute of Justice found that 60 percent of ex-felon offenders remain unemployed a year after their release.”

It is not easy to resist the urge to think of mass-murderous crimes as the singular actions of an individual.

I appreciate Earl Ofari Hutchinson‘s article because it brings together the many invisible and minor trials in life that collectively make daily stress unbearable. I finished the article amazed that there are fewer desperate crimes akin to Mixon’s. An uncomfortable thought.

Again, Hutchinson reminds us that the problems of incarceration, recidivism, education, unemployment and crime are inseparable:

Washington, D.C. is a near textbook example of that. Nearly 3,000 former prisoners are released and return to the district each year. Most fit the standard ex-felon profile. They are poor, with limited education and job skills, and come from broken or dysfunctional homes. Researchers again found that the single biggest factor that pushed them back to the streets, crime, violence and, inevitably, repeat incarceration was their failure to find work.

Q. Why do we warehouse people, break them, and then return them to society in a poorer position to cope?

A. Punitive and immovable laws, collective arrogance & utter denial.

With an estimated 600,000 prisoners either released or due for release in 2009, it’s about time we make a small change in our accomodations – especially given the size of change we expect of former prisoners.

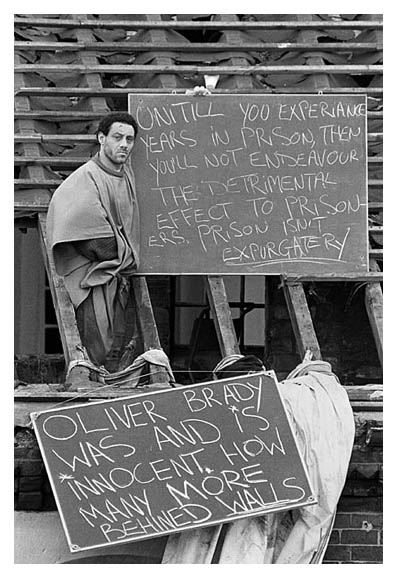

© 2009 Ged Murray

To append my last post about iconic photographs of rooftop inmates during the Strangeways riot of 1990 is a nod to the work of Ged Murray. Previous lamentations at the lack of Strangeways photography were premature on my part … I just had to keep digging.

© 2009 Ged Murray

These are my choice shots from a series of 20 Strangeways images on Ged Murray’s website. The image below of the two inmates in discussion is iconic (according to my brother). The silhouetted tower is instantly recognisable.

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

© 2009 Ged Murray

This last image of an inmate with signs took a large portion of my time. I am still thinking it over. Unerringly, I like the image. The shot bypasses the potency of icon and dilutes our consumption of events; returning our appreciation to more modest levels, focusing on the individual lives involved during a brief but pivotal moment in the history of British governmental prison policy.

© 2009 Ged Murray

__________________________________

Thanks to Ged Murray for his permission to publish the images.

The Strangeways riots in 1990 led to breakthroughs in the prison system. Photograph: Don McPhee for the Guardian

On April 1st 1990, began Britain’s largest prison riot in history. Strangeways may not mean a lot outside of the UK, but within, Strangeways, Manchester is synonymous with the romanticised image of the Northern criminal. The photographs of prisoners on the roof are iconic. Britons watched with shock.

Photo: Ged Murray for the Observer

Prison conditions had rarely been in public debate. Our level of shock was only equivalent to our level of apathy, prior. The general public were in awe of the unprecedented institutional collapse.

Prisoners occupied the roof for 25 days in front of round-the-clock media coverage. The protest ended when the final five prisoners surrendered themselves peacefully on 25th April.

The estimated damage was pegged between £50 and 100 million. The true cost for the HM Prison Service was lord chief justice, Lord Woolf’s subsequent damning report, which cited inmate frustration and poor prison conditions as a main reasons for the riot.

Photo: Ged Murray for the Observer

According to the Guardian – which includes a transcript of the prevailing exchange between proctor and prisoners – the stirrings of unrest began in the chapel following the 10am service. Prison officers evacuated the chapel and then (arguably) too hastily other areas of the prison. Inmates using keys taken from chapel guards released other inmates. Soon the overcrowded and understaffed facility was no longer in the control of government authority.

Strangeways roof protest photographs are iconic because their subject was so unexpected. Britain had harboured class and political confrontation much in the past. But in the miners strikes and clashes with police, football hooliganism, the general strike violence could be in some way predicted. The circumstances for those prior tensions had been played out through media narrative. UK Prisons were neglected; they were in desperate conditions and we – the public – were oblivious.

Don McPhee

Photographs of the Strangeways riot are hard to come by but I have gleaned a few from the web. In doing so I came across the work of the late Don McPhee.

I strongly urge you to watch this slideshow of his work.

McPhee had a 2005 exhibition at the Manchester Art Gallery and is a fondly remembered northern talent. He was a crucial part of the alternative editorial voice of the Guardian at that time. That distinctly Northern paper is now internationally distributed & respected.

Miners sunbathing at Orgreave coking plant. Photograph: Don McPhee

_______________________________________________________

Here is the inevitable percolating legacy of Strangeways in public dialogue.

Here, Eric Allison makes a succinct argument for British prison reform.

And here is the UK Parliament debate in 2001, ten years after the January, 1991 publication of Woolf’s report reviewing the response to the report recommendations.

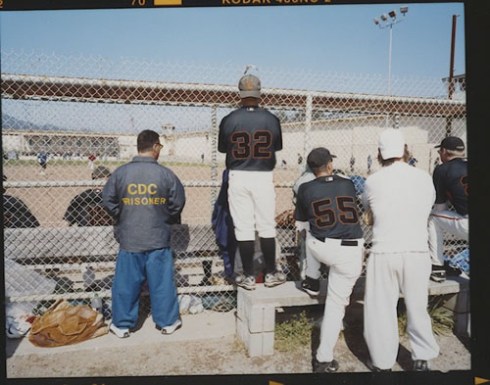

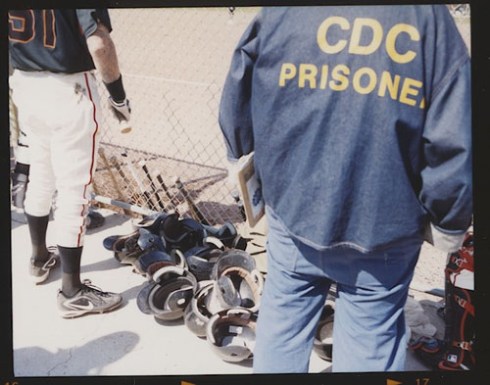

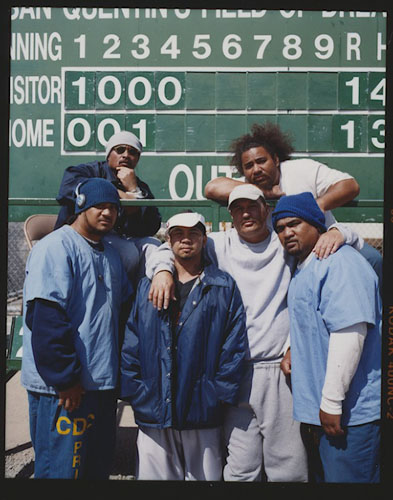

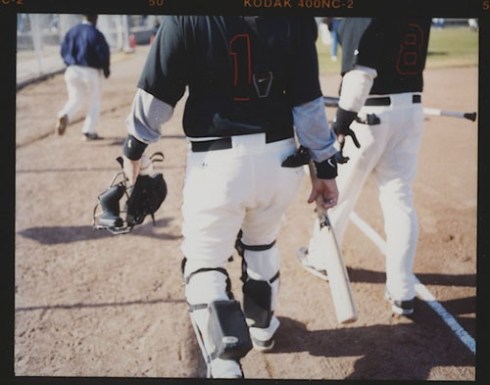

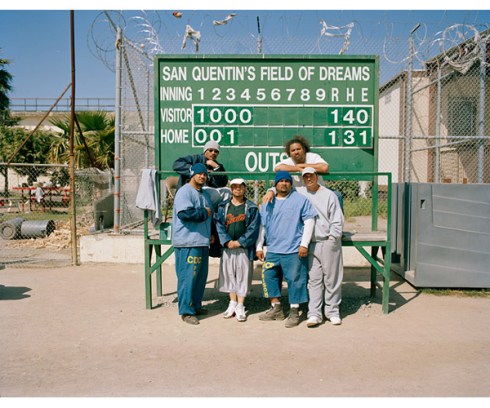

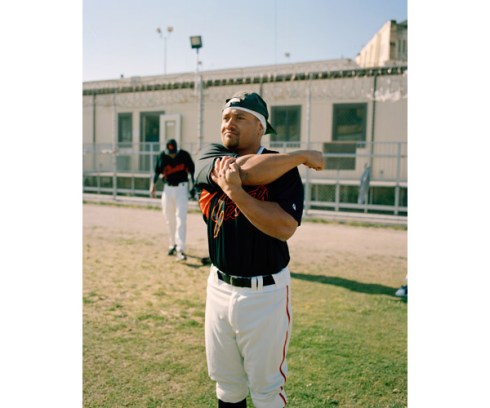

Last week, I threw up a quick post featuring Emiliano Granado’s website images of his photographs of the San Quentin Giants. Here, Granado shares previously unpublished contact sheet images, his experiences and lasting thoughts from working within one of America’s most notorious prisons.

What compelled you to travel across the US to photograph the story at San Quentin?

This was actually a magazine assignment for Mass Appeal Magazine. However, the TOTAL budget was $300, so it really turns out to be a personal project after the film, travel expenses, etc. So, the simple answer to the question is that I’m a photographer. I’m curious by nature. Part of the reason I’m a photographer is to study the world around me. I like to think of myself as a social scientist, except I don’t have any scientific method of measuring things, just a photograph as a document.

With that in mind, it would be crazy of me to NOT go to San Quentin! I’d never been in a correctional institution but I’ve always been fascinated by them. If you look through my Tivo, you’ll see shows like COPS, Locked Up, Gangland, etc. I was also a Psychology major in college and remember being blown away by Zimbardo’s prison experiment and other studies. Basically, it was an opportunity to see in real life a lot of what I’d seen on TV or read in books. And as a bonus, I was allowed to photograph.

What procedures did you need to go through in order to gain access?

I was amazed at the lack of procedure. The writer for the story had been in touch with the San Quentin public relations people, but that was it. There was plenty of other media there that day. It was opening day of the season, so I guess it made for a minor local news story.

I’m pretty sure SQ prides itself in being so open and showcasing what a different approach to “reform” looks like.

It is my opinion that San Quentin is one of the best-equipped prisons in California to deal with a variety of visitors. Did you find this the case?

Definitely. Access was very easy. They barely searched my equipment! Parking was easy. I was really surprised at how easy and smooth the process was. Not to mention there were many other visitors that day (an entire baseball team, more media, local residents playing tennis with inmates, etc).

Did your preparation or process differ due to the unique location?

Definitely. I usually work with a photo assistant and that couldn’t be coordinated, so I was by myself. I packed as lightly as I could and prepared myself for a fast, chaotic shoot. Some shoots are slow and methodical, and others are pure chaos. I knew this would be the latter.

One thing I didn’t think about was my outfit. SQ inmates dress in denim, so visitors aren’t allowed to wear denim. Of course, I was wearing jeans. The officers gave me a pair of green pajama pants. I’m glad they are ready for that kind of situation.

You are not a sports shooter per se. You took portraits of the players and spectators of inmate-spectators. How did you choose when to frame a shot and release the shutter?

Correct. I’m definitely not what most people would consider a sports photographer. I don’t own any of those huge, long lenses. However, I photograph lots of sporting events. I think of them as a microcosm of our society. There are lots of very interesting things happening at events like this. Fanaticism, idolatry, community, etc. Not to mention lots of alcohol and partying – see my Nascar images!

Hitting the shutter isn’t entirely a conscious decision. That decision is informed by years of looking at successful and unsuccessful images. It’s basically a gut instinct. There are times that I search for a particular image in my head, but mostly, it’s about having the camera ready and pointed in the right direction. When something interesting happens you snap.

There are photographers that come to a shoot with the shots in their head already. They produce the images – set people up, set up lighting, etc. Then there are photographers that are working with certain themes or ideas and they come to the location ready to find something that informs those ideas. I’m definitely the latter. There is a looseness and discovery process that I really enjoy when photographing like this. It’s like the scientist crunching numbers and coming to some new discovery.

A lot of photo editors say the story makes the story, not the images. Finding the story is key. Do you think there are many more stories within sites of incarceration waiting to be told?

I’m not sure I agree with that. I always say that a photograph can be made anywhere. Even if there is no story, per se. I definitely agree that a powerful image along with a powerful story is better, but a photograph can be devoid of a story, but be powerful anyway.

Every person, every place, everything has a story. So yes, there are millions of untold stories within sites of incarceration. Hopefully, I’ll be able to tell some of them.

Having had your experience at San Quentin, what other photo essays would you like to see produced that would confirm or extend your impressions of America’s prisons?

Man, there are millions of photos waiting to be made! I’m currently trying to gain access to a local NYC prison to continue my work and discover a bit more about what “Prison” means. Personally, I’d love to see long-term projects about inmates. Something like portraits as new inmates are processed, images while incarcerated, and then see what their life is like after prison. Their families, their victims, etc. And of course, if any photo editor wants to assign something like that, I’d love to shoot it!

Anything you’d like to add to help the reader as they view your San Quentin Baseball photographs?

Yes. When I walked in to the yard, I didn’t know what reaction I would get from the inmates. Everyone was super friendly and willing to be photographed. Everyone wanted to tell me their story. I’m not sure how different their reaction would have been to me if I didn’t have a camera, but I was pleasantly surprised. At first, I felt like an outsider and fearful, but after an hour or so, I felt comfortable and welcome. It was a weird experience to think the guy next to me could be a murderer (and there were, in fact, murderers on the baseball team), and not be afraid. There was this moral relativism thing going on in my head. These people were “bad,” yet they were just normal guys that had made very big mistakes. I left SQ thinking that pretty much any one of us could have ended up like them. Given a different set of circumstances or lack of access to social resources (e.g. education, money, parenting, etc) I could very easily see how my own life could have mirrored their life.

And finally, can you remember the opposition?

I don’t remember who they were playing, but I do remember that their pitcher had played in the Majors and even pitched in a World Series. I believe the article that finally ran in Death + Taxes magazine mentions the opposition.

ALL IMAGES © 2009 EMILIANO GRANADO

Authors note: Huge thanks to Emiliano Granado for his thoughtful responses and honest reflections. It was a pleasure working with you E!

Housekeeping. At the end of my previous post on Emiliano’s work, I postured when San Quentin would get more sports teams for the integration of prisoners and civilians. Emiliano has answered that for me in this interview. He observed locals playing tennis and also states San Quentin also has a basketball team.

With Emiliano‘s permission I have lifted these images straight from his website. We are working together on an interview for a second post on his work (scheduled for next week). It will include previously unpublished and untouched images from his contact sheets. Please stay tuned for that. Meanwhile enjoy my personal selection of six preferred prints.

ALL IMAGES © 2009 EMILIANO GRANADO

_____________________________________________

The San Quentin Giants are well known in the San Francisco Bay Area. I have met a couple of guys in the past who’ve played inside the walls during regular season – it is not unusual.

In an ideal world, the to and fro of public in and out of prison would be without restriction, threat or security protocol. This way, society could fear inmates less and inmates would not be institutionalised to the extent they are today.

I realise this is pie-in-the-sky thinking as the minority of seriously dangerous prisoners necessarily dictate the need for stringent controls. Still it doesn’t mean that increasingly trusted and regular contact between inmate and no-inmate populations cannot be our ideal to shoot for. Smaller and purposefully designed institutions would certainly be the first step in this sea change.

The scheduled games for the San Quentin Giants baseball team are the closest approximation to genuine & normalised interaction between inmate and non-inmate populations. When will San Quentin get a basketball team? Or any other teams for that matter?

____________________________________________

Check out these sources for further information on the San Quentin Giants. Press Enterprise – Long Article and Audio, Mother Jones article – Featuring Granado’s photography, California Connected – Video, Christian Science Monitor – Long article and video, NPR Feature – Audio.

And, if you are really engrossed you can always purchase Bad Boys of Summer, a recent documentary from Loren Mendell and Tiller Russell.