You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison’ tag.

Inmate Jeff Curbow, 40, says he improved a watering system for the moss after others built a special hut for it at Cedar Creek Corrections Center in Littlerock, Thurston County. Credit: Ken Lambert / The Seattle Times.

Prison Photography always looks to visual sources that represent incarcerated peoples from a different perspective. Some of the best opportunities to do this is with images of prisoners employing their time in job placements, self-growth programmes and/or restorative justice & community education projects.

A Cedar Creek inmate and researcher in the Prison Moss Project studies mosses. Credit: Nalini Nadkarni of Evergreen State College

The Prison Moss Project, part of the Washington Department of Corrections‘ sustainability efforts uses prisoners time for the benefit of multiple causes. The project studies the growth of different mosses, cultivates the fastest growing species and sells them commercially as an alternative to mosses stripped from America’s temperate rain forests. Harvested mosses constitute a $265 million/year business. 90% of mosses come from Pacific Northwest forests. The majority of mosses are used for short lived floral-arrangement. Moss can take between 20 to 40 years to regrow even a small patch of a few square feet.

The beauty of this model based on simple scientific observation and applied methods is that it is replicable the world over. And, the business that results makes sense too.

A Cedar Creek inmate and researcher in the Moss-in-Prisons project tends the garden. Credit: Nalini Nadkarni

So, the benefits? First and foremost, the inmates at Cedar Creek, a minimum security facility in the rural southwest of Washington enjoy daily active learning. Prison staff have described the facility as one without idle time among its inmate population. Engaging the bodies and minds of frequently docile populations is the first step in combating recidivism.

Concurrently, tax-payers (economically-efficient prisons), tourists (untouched old growth forests) and global citizens (robust ecological legacies) all benefit too. Finally, all this pales in comparison to the rewards for the Pacific Northwest old growth forests, which in future will not suffer unsustainable tree-stripping and moss harvesting.

A Cedar Creek inmate and researcher in the Prison Moss Project in the purpose built greenhouses. Credit: Nalini Nadkarni

How did all this start? Two convergent forces came together. The first was a general move by the Washington Department of Corrections to improve its carbon footprint, sustainability and opportunities for its inmates. This involved composting, recycling, organic farming, beekeeping at selected facilities. This green awakening fell into step with Nalini Nadkarni‘s need for extended and immediate research into moss varietal growth patterns.

Nadkarni has been called the “Queen of the Forest Canopies”. I am not one for personality worship, but let’s just say her work is socially – as well as environmentally – responsible, she knows how to work media channels, her message is imperative and the Evergreen State College in Olympia is very lucky to have her on faculty. She co-founded the Research Ambassador Program at Evergreen, which seeks to combine academic and non-academic practitioners to widen the reach of environmental dialogue and deliver relevant forms of communication to different groups; from inner city youth, to business CEOs.

It’s all about respectful communication, and it’s all for the benefit of our environmental futures.

Daniel Travatte, 36, suits up to check on the Italian honey bees he cares for at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest, Wash. on Friday, Oct. 17, 2008. The bees are part of a program to help the prison be more environmentally green. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

Inmate, Daniel Travatte, tends the Italian honey bees he cares for at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest, WA. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

The media coverage of this programme has often focused on the story of a young inmate who, since release, secured a biochemistry PhD full ride scholarship at the University of Nevada, Reno. He was imprisoned after accidentally killing his friend with his sports rifle in his student apartment. Four years later, he has continued the exceptional academic track he seemed destined to follow. It is a testament to the Washington Department of Corrections and Nalini Nadkarni (his mentor during time served) that his life has been delayed rather than destroyed.

But, he surely is an atypical case and it is a case that obscures the facts about the sustainable projects in operation at Cedar Creek. Not every inmate is a PhD candidate, but every inmate is a willing recipient of education – especially environmental education which, in many cases, is totally novel. Environmental education carries an almost redemptive message in that your actions can directly benefit everyone in modest but crucial ways. Actions based upon this new learning can be very therapeutic. Responsibility for oneself and other human beings is not separate from responsibility for our shared environment.

Inmates Robert Day (left) and Brian Deboer (right) check on plants in one of the organic gardens at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest, Washington, on Friday. The minimum-security prison has adopted many environmental and cost saving practices. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

I have discussed sustainability efforts in California’s prison system before. In closing I’d like to repeat the sentiments of Cedar Creek superintendents who, in attempts to convince the public of the utility of this program, talk of the direct reduction in operating costs at the facility. If commentators such as myself want to espouse the rehabilitative value also then so be it. Doubters now have firm fiscal, quantitative evidence – in addition to qualitative inmate testimonies – to shape their support for sustainability programmes in prisons. WDC senior staff are adamant Cedar Creek is the correctional model to follow in the 21st century.

Inmate Robert Knowles pitches plant stalks into a compost pile Oct. 17 at the Cedar Creek Corrections Center in rural southwest Washington. The minimum-security prison has adopted many environmental and cost-saving practices. Credit: John Froschauer/AP

There are many resources out there on the Prison Moss Project and Nalini Nadkarni‘s ongoing evangelism. I personally would recommend in this order … Nalini Nadkarni’s recent TED presentation about the opportunities for academic & non-academic communities to unite for greater good; this extended video from KCTS (9 minutes); this interview with Nadkarni; a recent Mother Jones summary of her projects and two media reports (1), (2).

While not related to the work of a single photographer or project, the lines of argument proffered by Subtopia are so resonant that Prison Photograph Blog feels the diversion justified. Through summary of the four chosen articles, we can gaze upon the complexity and omnipotence of incarceration in our frantic, contested global society. Subtopia’s images will knock you on your arse!

The analysis of Bryan Finoki at Subtopia consistently join the dots between geopolitics & biopolitics; movement & paralysis; spatial theory and spatial reality. Unsurprisingly, for a writer in the 21st century, his interest in the production of structures & networks, often leads him to theories of militarised space.

I am in awe of Subtopia’s output. From lengthy and comprehensive issue-based summaries; to purposed surveys; from fine image-editing; to diverse links and sources in each post. Finoki serves up rigorous analysis, or entertainment, but usually both.

© 2009 Subtopia/Brian Finoki

Over the past couple of years Finoki has submitted a few pieces on “The Prison”. Subtopia’s preoccupation with power and spatial production means carceral sites/archipelagos are referenced frequently. Finoki has been keen to unravel the mysteries of the Global War on Terror (GWOT), its structures and its legacies – this always means dealing with detention, rendition, and construction (that can be visible, but more often invisible.)

Article One – Fantasy Prison is a meditation on potential prison architectures spurred by the 2007 Creative Prison project a collaboration between architect Will Alsop prisoners at HMP Gartree to redesign corrective and rehabilitative space. Two things struck me about the suggestions made by prisoners. 1) They were most afraid of attack from other inmates, and therefore an option to lock themselves IN was a shared high priority, and 2) They wanted to include a designated photo-room within the visitors center to allow for photography and variant backgrounds. I have posted before about manifestly curious prison-polaroid aesthetic. This article also threw up the crucial social responsibilities of architects & designers in a time of prison expansion, most notably the Prison Design Boycott launched in 2004 by the group Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR).

A rendering of Will Alsop’s new corrections landscape, developed in collaboration with prisoners, resembles a cross between Communist-era housing blocs and a series of South Beach condos. Courtesy Alsop Architects

I have been a fan of Alsop’s work since his 2005 hypothetical SuperCity project which would subsume my hometown in the North.

Article Two – Floating Prisons is a historical survey of sea-faring, carceral solutions by warring and colonising nations. Finoki maps the use of prison ships from 18th & 19th century economic necessity to transport human cargo to contemporary manoeuvrings in avoidance of international law. He makes reference to the convenience use of islands as sites of detention, the use of ships as temporary housing in leiu of land locked sites, and the dubious experiments in swapping refugees held in off-shore camps. The summary was to say that new legal definitions and controls are creeping in giving one the sense, “refugees and migrants are just an excess of biomass to be herded around on prison islands or in prison vessels, traded like geo-economic commodities, removed and disposed of like capitalist human waste, reinforcing the state of exception that goes on re-organizing the architectural spheres of global migration.” Phenomenal.

The Vernon C. Bain is a prison barge operated by the City of New York, housing 800 prisoners in a medium and maximum security facility. Built in 1992 at a cost of $ 161 Million means it would have been cheaper to send the inmates to Harvard instead. (Source)

Article Three – “Block D” enters the Pantheon of GWOT Space is a meditation on the totality of restricted space across the globe – in multiple nations – in order to sustain military operations. The point of the survey (which includes previously known sites such as Guantanamo, Baghdad’s ‘Green Zone’, Bagram Theater Internment Facility, US homeland immigrant detention facilities, and Taxi networks for rendition) is to add another site to the list: “Block D” in Pul-e-Charki Prison just east of Kabul, Afghanistan.

With persistent references to journalists’ work for the BBC, New York Times and Washington Post, Finoki summarises, ” ‘Block D’ or ‘Block 4’ as it is also apparently known: a newly built detention facility [is] quickly becoming understood as the Asian corollary of Guantánamo Bay. No matter, it is another utterly disturbing black hole in the universe of legally suspect and secret space.” Finoki doesn’t focus on the conditions of detention but rather America’s self-created legal imbroglio.

Nearly a year after writing, this analysis seems prophetic now, as the American public is slowly coming to realise that Obama’s closure of Gitmo doesn’t necessarily magic away the human rights issues … only shifts them somewhere slightly more obscured. As with Gitmo, one expects Block D to focus the new rounds of jousting between the same ideological stakeholders.

Pul-e-Charkhi prison, Kabul, Afghanistan. Construction began in the 1970s by order of then-president Mohammed Daoud Khan and was completed during the Soviet invasion (1979-89). The prison was notorious for torture and abuses under the control of Afghanistan's communist government following the invasion by the Soviet Union. (Source)

Article Four – The Spatial Instrumentality of Torture is a stomach-pounding dose of reality in the form of an interview with Tom Hilde, Research Professor in the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland. I will not offer a synopsis, just encourage you to read through it. The interview is illustrated in part by Prison Photography‘s favourite Richard Ross.

Hilde ends with the sobering words, “The secrecy of much of the US torture program, its physical spaces, and its extent has certainly kept public debate rather subdued. But I think the dualistic moral framework has been even more corrosive of a public understanding of torture in general and the consequences of American torture in particular. When a majority of Americans say that torture is acceptable for some purposes, I think they have the fantasy of the ticking timebomb, and likely racism in many cases, in the backs of their minds.”

Camp X-Ray, Guantánamo, Cuba. The facility has not been used since early 2002, and recent heavy rains at Guantánamo Bay have brought about overgrowth. Credit: Kathleen T. Rhem

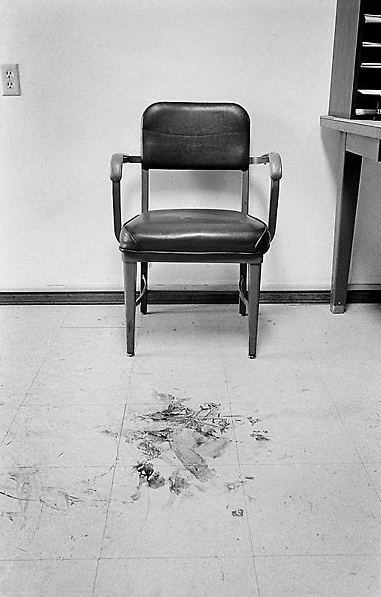

Alabama Death House Prison, Grady, AL, 2004. Silver print photograph. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Stephen Tourlentes photographs prisons only at night for it is then they change the horizon. Social division and ignorance contributed to America’s rapid prison growth. Tourlentes’ lurking architectures are embodiments of our shared fears. In the world Tourlentes proposes, light haunts; it is metaphor for our psycho-social fears and denial. Prisons are our bogeyman.

These prisons encroach upon our otherwise “safe” environments. Buzzing with the constant feedback of our carceral system, these photographs are the glower of a collective and captive menace. Hard to ignore, do we hide from the beacon-like reminders of our social failures, or can we use Tourlentes’ images as guiding light to better conscience?

Designed as closed systems, prisons illuminate the night and the world that built them purposefully outside of its boundaries. “It’s a bit like sonic feedback … maybe it’s the feedback of exile,” says Tourlentes.

Stephen Tourlentes has been photographing prisons since 1996. His many series – and portfolio as a whole – has received plaudits and secured funding from organisations including the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Massachusetts Cultural Council and Artadia.

Stephen was kind enough to take the time to answer Prison Photography‘s questions submitted via email.

Penn State Death House Prison, Bellefonte, PA, 2003. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Carson City, Nevada, Death House, 2002. Gelatin silver print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Blythe Prison, California. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Pete Brook. You have traveled to many states? How many prisons have you photographed in total?

Stephen Tourlentes. I’ve photographed in 46 states. Quite the trip considering many of the places I photograph are located on dead-end roads. My best guess is I’ve photographed close to 100 prisons so far.

PB. How do you choose the prisons to photograph?

ST. Well I sort of visually stumbled onto photographing prisons when they built one in the town I grew up in Illinois. It took me awhile to recognize this as a path to explore. I noticed that the new prison visually changed the horizon at night. I began to notice them more and more when I traveled and my curiosity got the best of me.

There is lots of planning that goes into it but I rely on my instinct ultimately. The Internet has been extremely helpful. There are three main paths to follow 1. State departments of corrections 2. The Federal Bureau of Prisons and 3. Private prisons. Usually I look for the density of institutions from these sources and search for the cheapest plane ticket that would land me near them.

Structurally the newer prisons are very similar so it’s the landscape they inhabit that becomes important in differentiating them from each other. Photographing them at night has made illumination important. Usually medium and maximum-security prisons have the most perimeter lighting. An interesting sidebar to that is male institutions often tend to have more lighting than female institutions even if the security level is the same.

Holliday Unit, Huntsville, Texas, 2001. Gelatin silver print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Springtown State Prison, Oklahoma, 2003. Archival pigment print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Death House Prison, Rawlins, Wyoming, 2000. Archival pigment print. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Arkansas Death House, Prison, Grady, AK, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. Are there any notorious prisons that you want to photograph or avoid precisely because of their name?

ST. No I’m equally curious and surprised by each one I visit. There are certain ones that I would like to re-visit to try another angle or see during a different time of year. I usually go to each place with some sort of expectation that is completely wrong and requires me to really be able to shift gears on the fly.

PB. You have described the Prison as an “Important icon” and as a “General failure of our society”. Can you expand on those ideas?

ST. Well the sheer number of prisons built in this country over the last 25 years has put us in a league of our own regarding the number of people incarcerated. We have chosen to lock up people at the expense of providing services to children and schools that might have helped to prevent such a spike in prison population.

The failure is being a reactive rather than a proactive society. I feel that the prison system has become a social engineering plan that in part deals with our lack of interest in developing more humanistic support systems for society.

PB. It seems that America’s prison industrial complex is an elephant in the room. Do you agree with this point of view? Are the American public (and, dare I say it, taxpayers) in a state of denial?

ST. I don’t know if it’s denial or fear. It seems that it is easier to build a prison in most states than it is a new elementary school. Horrific crimes garner headlines and seem to monopolize attention away from other types of social services and infrastructure that might help to reduce the size of the criminal justice system. This appetite for punishment as justice often serves a political purpose rather than finding a preventative or rehabilitative response to societies ills.

State Prison, Dannemora, NY, 2004. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Prison, Castaic, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Federal Prison, Atwater, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Utah State Death House Complex, Draper, UT, 2002. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. How do you think artistic ventures such as yours compare with political will and legal policy as means to bring the importance of an issue, such as prison expansion, into the public sphere?

ST. I think artists have always participated in bringing issues to the surface through their work. It’s a way of bearing witness to something that collectively is difficult to follow. Sometimes an artist’s interpretation touches a different nerve and if lucky the work reverberates longer than the typical news cycle.

PB. In your attempt with this work to “connect the outside world with these institutions”, what parameters define that attempt a success?

ST. I’m not sure it ever is… I guess that’s part of what drives me to respond to these places. These prisons are meant to be closed systems; so my visual intrigue comes when the landscape is illuminated back by a system (a prison) that was built by the world outside its boundaries. It’s a bit like sonic feedback… maybe it’s the feedback of exile.

PB. Are you familiar with Sandow Birk’s paintings and series, Prisonation? In terms of obscuring the subject and luring the viewer in, do you think you operate similar devices in different media?

ST. Yes I think they are related. I like his paintings quite a lot. The first time I saw them I imagined that we could have been out there at the same time and crossed paths.

PB. Many of your prints are have the moniker “Death House” in them, Explain this.

ST. I find it difficult to comprehend that in a modern civilized society that state sanctioned executions are still used by the criminal justice system. The Death House series became a subset of the overall project as I learned more about the American prison system. There are 38 states that have capital punishment laws on the books. Usually each of these 38 states has one prison where these sentences are carried out. I became interested in the idea that the law of the land differed depending on a set of geographical boundaries.

Federal Prison, Victorville, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Prison Complex, Florence, AZ, 2004. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

Lancaster State Prison, Lancaster, CA, 2007. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. Have you identified different reactions from different prison authorities, in different states, to your work?

ST. The guards tend not to appreciate when I am making the images unannounced. Sometimes I’m on prison property but often I’m on adjacent land that makes for interesting interactions with the people that live around these institutions. I’ve had my share of difficult moments and it makes sense why. The warden at Angola prison in Louisiana was by far the most hospitable which surprised me since I arrived unannounced.

PB. What percentage of prisons do you seek permission from before setting up your equipment?

ST. I usually only do it as a last resort. I’ve found that the administrative side of navigating the various prison and state officials was too time consuming and difficult. They like to have lots of information and exact schedules that usually don’t sync with the inherent difficulty of making an interesting photograph. I make my life harder by photographing in the middle of the night. The third shift tends to be a little less PR friendly.

PB. What would you expect the reaction to be to your work in the ‘prison-towns’ of Northern California, West Texan plains or Mississippi delta? Town’s that have come to rely on the prison for their local economy?

ST. You know it’s interesting because a community that is willing to support a prison is not looking for style points, they want jobs. Often I’m struck by how people accept this institution as neighbors.

I stumbled upon a private prison while traveling in Mississippi in 2007. I was in Tutweiler, MS and I asked a local if that was the Parchman prison on the horizon. He said no that it was the “Hawaiian” prison. All the inmates had been contracted out of the Hawaiian prison system into this private prison recently built in Mississippi. The town and region are very poor so the private prison is an economic lifeline for jobs.

The growth of the prison economy reflects the difficult economic policies in this country that have hit small rural communities particularly hard. These same economic conditions contribute to populating these prisons and creating the demand for new prisons. Unfortunately, many of these communities stake their economic survival on these places.

Kentucky State Death House, Prison, Eddyville, KY, 2003. © 2009 Stephen Tourlentes

PB. You said earlier this year (Big, Red & Shiny) that you are nearly finished with Of Lengths and Measures. Is this an aesthetic/artistic or a practical decision?

ST. I’m not sure if I will really ever be done with it. From a practical side I would like to spend some time getting the entire body of work into a book form. I think by saying that it helps me to think that I am getting near the end. I do have other things I’m interested in, but the prison photographs feel like my best way to contribute to the conversation to change the way we do things.

________________________________________

Author’s note: Sincerest thanks to Stephen Tourlentes for his assistance and time with this article.

________________________________________

Stephen Tourlentes received his BFA from Knox College and an MFA (1988) from the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, where he is currently a professor of photography. His work is included in the collection at Princeton University, and has been exhibited at the Revolution Gallery, Michigan; Cranbook Art Museum, Michigan; and S.F. Camerawork, among others. Tourlentes has received a John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, a Polaroid Corporation Grant, and a MacDowell Colony Fellowship.

________________________________________

This interview was designed in order to compliment the information already provided in another excellent online interview with Stephen Tourlentes by Jess T. Dugan at Big, Red & Shiny. (Highly recommended!)

Morgan Spurlock is a decent guy. I’d like to have a beer with him. He lays it out straight. Prisons & jails are boring and hopeless. He knows this because he spent 30 days in a county jail just outside of Richmond, Virginia.

Spurlock nails it. “One of the most surprising things about prison is that you are pretty much left on your own. all you can do is kinda suck it up and fall into a pattern. I’m gonna get up, gonna eat, gonna play cards, gonna watch TV, gonna do some push ups, do some sits ups, write a letter, read a book….”

He continues, “People will be in their rooms or down here – just hanging out, you know, on the phones. The punishment is the monotony. This is it. You don’t have to think. You’re in jail. There is no thinking involved. And you’re feeding the machine. And you feel like that … you don’t feel like a person in a lot of ways.”

Spurlock elaborates “I haven’t seen a tree in over two week;, I haven’t seen one blade of grass; I haven’t breathed fresh air. It gets to you being in here … it really does. I see people like George and Randy who keep making the same mistakes over and over and over again. What is the system doing for these guys? They’re stuck! I see this cycle that were putting people in and punishing people for problems we could be helping them with. And the prisons and jails are just becoming a dumping ground. It really is a place that feels hopeless.”

Spurlock even challenged his sanity by agreeing to a 72 hours stretch in solitary confinement. Spurlock couldn’t comprehend how Randy (mentioned earlier) spent a year in solitary.

Great series. Great episode. Sobering reality. Spend 45 minutes of your life and witness the monotonous and expensive warehousing of society’s misfits.

An interior view of the dining facility at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. Wathiq Khuzaie for Getty Images Europe.

Yesterday, my good friend Debra Baida sent me through the link to the New York Times Abu Ghraib – Baghdad Bureau Blog. This came at the same moment I was preparing a post to discuss the first images to come out of the renamed, refurbished and relaunched Baghdad Central Prison.

By far the best, and possibly the only, extended photo essay of Abu Ghraib Baghdad Central Prison is by Wathiq Khuzaie of Getty Images Europe. There is also this brief video from the BBC.

Iraqi security personnel stand guard at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. The Iraqi Ministry of Justice has renovated and reopened the previously named "Abu Ghraib" prison and renamed the site to Baghdad Central Prison. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe

New Era, New Penology

The BBC noted, “Along with the change of name, the Iraqi justice ministry is trying to change both image and reality, billing it as a model prison, open to random inspection by the Red Cross and other humanitarian organisations.”

This transparency is a refreshing change to the policy of Abu Ghraib’s former operators. The work is not yet complete though and the upgrade is ongoing. The BBC describes, “[The prison] will eventually be the city’s main jail, holding about 12,000 inmates. Initially, only one of its four sections will be used. There are already about 300 prisoners there to test it out and, once the prison has been officially inaugurated, that figure will rise to 3,500.”

So, not only do Iraqi authorities want to repurpose the institution, they want to make it the penal institution of “The New Iraq”. This is an ambitious policy riddled with dangers; the site is loaded with memory and controversy. As the New York Times notes, “the promise of a new era can also be a time for remembrance.”

I highly recommend one goes onto read accounts from Iraqis, correspondents and photographers who lived and recorded Abu Ghraib’s recent history, particularly photographer Tyler Hicks’ account of Saddam’s prison amnesty in October 2002 that turned from celebration to human catastrophe.

Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe

An interior view of one of the cells at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe

Two things struck me about the photographic series of the new prison. Firstly, the number of flags, insignia and national colours across walls, above fences and emblazoned on uniforms. The Iraqi authorities have stamped their identity all over this project. It is the presentation necessary to supersede Abu Ghraib’s reputation.

Secondly, the pastel palette of many of the interior shots – namely the ubiquitous lilac. I want to know who has the decision-making power at Baghdad Central Prison! However, I suspect lilac paint was cheap and readily available; so it wasn’t so much a decision – more a fact created by circumstance.

Interior view of the barbers shop at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe.

Following that logic, one could presume lilac and purple fabric & thread is also at a surplus in Baghdad…

Interior view of sewing machines at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe.

I don’t want to sound facetious, I was just shocked by the light purple, which according to colour theory is supposed to evoke emotional memory and nostalgia. Darker purples are supposed to represented, nobility, royalty and stability. From those evocations one is instilled with wisdom, independence, dignity and creativity.

If Baghdad Central Prison is to spur such emotional response in its inmate population it will succeed where many, many prisons have failed.

Basically, I am hopeful that the new prison can operate justly and succeed with the rehabilitation it emphasised this week. And despite all the lilac, soft-furnishings and current open media access – in reality it remains a prison with doors, locks and guards.

Interior view of cell doors at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. The Iraqi Ministry of Justice has renovated and reopened the previously named "Abu Ghraib" prison and renamed the site to Baghdad Central Prison. According to the Iraqi Ministry of Justice about 400 prisoners were transferred to the prison which can hold up to 3000 inmates. The prison was established in 1970 and it became synonymous with abuse under the U.S. occupation. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe.

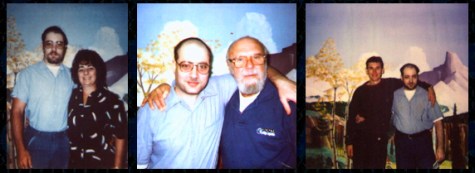

“Prison Polaroids: A Dispersed Portrait of American Life”

I was speaking to Sheila Pinkel recently about photography within prisons. She said only once had she been inside a prison with a camera of her own. We shared wonder at those photojournalists who through luck or nous gain access within US sites of incarceration.

Sheila explained that photography was conducted in the visiting rooms. Standard practice is for a correctional officer or fellow inmate to operate a Polaroid camera and sell the Polaroids at $2 each.

Imagine those Polaroids gathered together and the dialogue they’d rouse as a collection. But this portrayal of America is dispersed, and its dialogue is absent.

Susanville

Susanville

Dr Maria Kefalas, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Chicago noted the collection and display of Prison Polaroids in Promises I Can Keep, a book about mothers’ poverty in the US:

In the course of Kefalas’s fieldwork she was invited into more than a dozen living rooms that displayed a “Prison Polaroid”, sometimes held to the wall by a thumbtack or tucked into a framed family portrait on the television set. Prisoners, she learned, can have these taken for only (sic) a few dollars at the prison commissary and usually pen cheerful descriptions such as “Happy Birthday” or “I love you” on the back. When family members come to visit, the commissary photographer will, for a fee, commemorate the occasion with a keepsake Polaroid. One mother showed Kefalas a photo album of Polaroid photographs taken in the prisons’ visiting area – each commemorating one of the few times her daughter and her child’s father had been in the same room together over the course of the six years old’s life. the photos typically feature the inmate in his fluorescent orange department of corrections jumpsuit against a backdrop of a tropical beach scene, perhaps to give the illusion to the loved ones back home that their father is not in prison, but taking a much needed vacation.

San Quentin

San Quentin

After some digging I found this account:

In the processing room there is an inmate store where one can buy articles made by inmates and also buy these cards for $2, good for a snapshot of you and your friend taken in front of this large poster of a waterfall in the woods. I got one of these cards and when my friend and I went to get our picture taken I asked if we could have the dining room and everybody in it in the background. This was a big no-no, as people might be recognized in the photo. I didn’t know. We had our picture taken by an inmate with a Polaroid camera who later passed out the photos to the different tables. It turned out real nice.

San Quentin

Visitors are prohibited from bringing their own cameras or phones to the majority of US correctional facilities. Frequently the visitor buys two, one for the mantelpiece at home and one to return to the inmates cell. But there is no negative – just as there is no album. The Polaroids are dispersed across a nation. I think it would be fascinating to such Polaroids together.

Santa with VVGSQ members and supporters. San Quentin Prison visiting room - December 18, 2005. The VVGSQ has always supported the San Quentin Christmas Toy Program with toy donations as well as by running the program each year. The Warden has authorized the VVGSQ to sponsor this program and the group purchased the "Santa" suit, beard and wig that is used for an appearance of Santa to the children each year at the visiting room. The program benefits all the children who come to visit family at San Quentin during the Christmas season. Started in 1988, December 2008 will be the 20th year the program has been giving toys to the children who visit San Quentin.

In piecing together this online group of images, I found it difficult to come across images. This does not surprise me.

In what circumstances do people scan their Polaroids of a prison visit for online upload? Just a few; friends & family with blog updates; purveyors of the macabre; journals of the death-row inamtes; inmate support groups and children’s rights organisations.

Please alert me to any other sources.

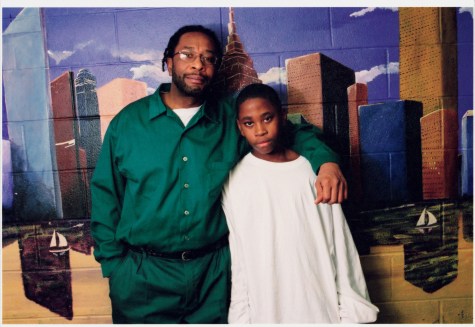

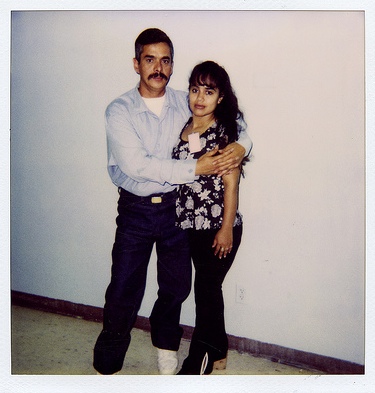

_______________________________

This is not a Polaroid but it is an image I came across here, with the enlarged image here. I had to include it. I challenge readers to find a better photographic portrait. The adult fights back tears and the child is solemn. Standing for the photo – for pride and for necessity – is a struggle for the father. The personalities are so strong, I wonder what words they have spoken to one another. Surely, the father’s outward show of emotion is typical of the sadness adults bear when behind bars, away from their children. I have no children. I can’t begin to know, even by comparison. These two portraits would excel as individual shots; to put them together is to light a firecracker under the seat of emotive curiosity.

Father and Son

I also found this image on Flickr, which has a stark backdrop by comparison.

Jail Visit?

Thoughts?

How about that as a potent exhibition just waiting to come together? Millions of Prison Polaroids in frames & drawers; homes & cells across America. The dispersed portrait of incarcerated Americans could be assembled in one place. The scale would be overwhelming and the juxtapositions endless. Let me know if the notion intrigues you as much as it intrigues me.

BURN Magazine, under the fiscal umbrella of the Magnum Cultural Foundation, have announced a $10,000 grant “to support [the] continuation of the photographer’s personal project. This body of work may be of either journalistic mission or purely personal artistic imperatives”

I am encouraging people to take on the difficult task of securing prolonged and necessary time with a prison/jail/detention-centre population in order to faithfully describe the stories and systems of its particular circumstance. On top of that your product must be “work is on the highest level”.

It’s a tall order but if you have carried out portrait or documentary photography in a site of incarceration before (I know many of you), then submit an application to continue that critical and valuable work. It will have to better than my attempt.

San Pedro Prison, La Paz. July 2008.

Hmm. On the same day I encourage photographers to attempt access into sites designed to be impenetrable, the government and police in my home country have introduced “laws that allow for the arrest – and imprisonment – of anyone who takes pictures of officers ‘likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism’.” (British Journal of Photography via In-Public)

BURN Magazine is a new(ish) venture by David Alan Harvey whose got a Magnum portfolio and his own internets.