You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘San Quentin’ tag.

LEFT: Henry Montgomery, who has served 23 years in prison for homicide, serves the ball during a match at San Quentin State Prison. RIGHT: Guards stand watch over inmates in San Quentin’s recreational yard, which now includes a tennis court. © Rick Loomis LA Times

TENNIS AND THE CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS

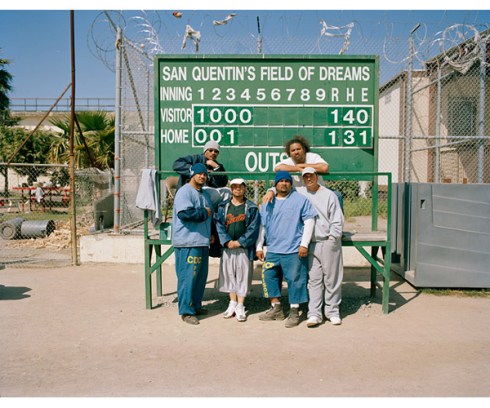

Last year, whilst featuring photo essays (here & here) on the San Quentin Giants baseball team, the photographer Emiliano Granado mentioned seeing tennis matches.

San Quentin sits on a Marin County promontory; every day, in the surrounding well-heeled communities deuce and lemonade are being served, but it was a stretch even for my imagination to envision games, sets and matches playing out inside those walls.

Kurt Streeter – for the Los Angeles Times – went to San Quentin to play a match and profile Don DeNevi, San Quentin’s 72 year old recreation director. DeNevi is largely responsible for the construction of the prison’s tennis court. Read Tennis is serious sport in San Quentin Prison.

THE PHOTOGRAPHS

Rick Loomis created a photo essay Tennis Inside the Walls of San Quentin of his own; the two works of journalism are a nice compliment.

LEFT: Henry Montgomery, 43, center, laughs with other inmates during a break in play. RIGHT: Raphael Calix watches the activity on one of the blocks at San Quentin. Calix is a regular on the tennis court. © Rick Loomis/Los Angeles Times

Green has strong emotional correspondence with safety. Green is the most restful color for the human eye; it can improve vision. Green suggests stability and endurance. Green is used to indicate safety when advertising drugs and medical products. Dull, darker green is commonly associated with money, the financial world, banking, and Wall Street. Dark green is associated with, greed, and jealousy. Aqua green is associated with emotional healing and protection.

Source

I was looking over the following images of the protest/vigil outside San Quentin Prison on the night of Stanley ‘Tookie’ Williams’ murder by the state of California.

The verdant tones of green dominate and they reminded me – like some ironic twist of a krypto-knife – of California’s death-chamber itself. San Quentin has since constructed itself a new fan-dangled killing suite … and it needed to. The Golden State had taken to injecting people with poison within its old hexagonal gas chamber.

The site became an insult to the escalating industry of death, out of sync with the newest sterile modes of person-erasure. The heavy air-locked lantern no longer suitable for the clinical 21st century methods of snuff so developed by scientists, physicians and judges.

The pea green pod that transports, transforms and accelerates passage to elsewheres; An echo of an echo-death-chamber..

One switch, one injection, one mistake, one outcome.

Two switches, two injections, two mistakes (original crime vs. retaliatory murder), two outcomes (original verdict vs. appeals all boiled in a single decision-cauldron).

A theatre reenactment. Perfect palette.

Source

Back in San Quentin, the gurney straps itself to itself.

Source

As a ten year old, I remember the same night time visions of green tinted destruction. John Major was in power and war seemed just.

I’ve seen them again recently …

Different century, same annihilation.

People will disintegrate, body parts will fall off, limbs will be poisoned and charred.

Democracy will teleport itself for its own arrogance, implicating a dictatorship and a sorry hybrid shall limp to an uncertain future.

And the toll shall be personal, unsuspected, for the love of the state and its rhetoric.

And the children will be the unhindered beneficiaries of a world not of their own, but the world of their violent predecessors, their decisions, amalgamations, actions and murders.

Kids become sad reminders that nostalgia, film photography and wildlife cinematics were forsaken before they could be rightfully demanded back. A new sterile age sports no death cells, no faces, no conscience, no history.

Immunology becomes the new high stakes industry …

…

…

By the way, have you ever noticed that the beat in Boards’ Kid for Today is the clickclack of a slide projector carousel?

Daniel Etter‘s project from Hohenschonhausen piggybacks on the story of Norbert Krebs to shape the narrative. Krebs was imprisoned in Hohenschonhausen – the primary Stasi Prison in the GDR – for questioning the reliability of election results. He now leads guided tours. In sites such as these, it is a solemn privilege to hear the first-hand experiences of anyone persecuted by prior political powers.

It is as much a dilemma for communities and nations as it is an opportunity to write and affirm history, when former prisons are repurposed. Prison museums, peace museums and memorials are all common solutions to the troublesome, contested and understandably hated sites.

Prison museums are very common – here’s a (non exhaustive) list of links.

US

Alcatraz Island

Texas Prison Museum

Angola Prison Museum, Louisiana

San Quentin Prison Museum

Folsom Prison Museum

Eastern State Penitentiary

Sing Sing Prison Museum

Old Montana Prison Museum

Burlington County Prison Museum

Museum of Colorado Prisons

Wyoming Frontier Prison

Elsewheres

Dartmoor Prison Museum, England

Lancaster Castle, England

The Clink Prison Museum, London

Robben Island Museum, South Africa

Port Arthur Historic Site, Tasmania, Australia

Fremantle Prison, Western Australia

Abashiri Prison Museum, Japan

The Changi Museum, Singapore

Kresty Prison Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

If your interest is piqued, consult this huge inventory of prison museums from across the globe.

And here’s a random selection of photographs of a selection of prison museums.

Note: I have touched upon Hohenschonhausen before here and here.

I’d like to feature here two very separate projects. If you’ll allow me, I want to overview Matej Kren’s Book Cell and think of the book literally as a sculptural physical constraint. At the same time, I’d like to introduce Herman Spector’s program of bibliotherapy at San Quentin Prison and frame the book as a pedagogical tool for control.

For his 2006 installation of Book Cell at the CAMJAP in Prague, Matej Kren stated:

The Book Cell Project repeats the recurring procedure, in the work of this artist, of piling up thousands of books, creating an architectonic structure where we are invited to step inside.

The memory and knowledge accumulated in the books gathered, closed and inaccessible, diverse and precious will be potentially recovered in the end, when all of the books can return to their function of being read, but meanwhile they will have been worked on as sculpting matter and as the spirit of the place where the artist intends to hold us: an hexagonal enclosure with a passage defined by mirrors that assure the vertigo of a fall, the ad infinitum fragmentation, the panic of spatial disorientation characteristic of a virtual infinity.

The fact that these structures are made from the library/archive of the hosting institution makes me shudder. CAMJAP claims a pride in this making the structures site specific.

Prague is a great literary city and the absurdity of being confined by books would be appreciated by Kafka, and yet Krens offers us a way out that Kafka never would. He intends that books return to use and are reborn into cultural thought.

Kren’s literal use of bound knowledge in the fortification of space calls to mind other powerful (if less poetic) uses of books in controlling inmate populations. I’m thinking specifically of Herman Spector’s program of Bibliotherapy at San Quentin State Prison

From 1947 until 1968, Herman Spector was employed as senior librarian at San Quentin. He put in place a meticulous, long-term program offering 7-days-a-week library access and a choice from over 33,000 titles. By the end of his tenure he stated (not estimated, for he knew every book checked out) that 3,096,377 books had circulated through his system. His project drove up prisoner literacy and had inmates reading 98 books/year.

The project sounds nothing but positive and indeed it brought about much self improvement. But, remember this was a grand experiment with a captive audience and Spector had total control over the reading lists – and latterly, the outward correspondence and writing by San Quentin inmates. Spector employed censorship as readily as he conducted reading groups and assigned classic texts.

Five years ago I was fortunate to meet Eric Cummins, whose book The Rise and Fall of California’s Radical Prison Movement details Spector’s manipulations at San Quentin (Chapter Two: Bibliotherapy & Civil Death). It is the most thorough examination of that great experiment. Cummins writes:

‘Books, for Spector, were the “deathless weapons of progress” by which prisoners could be “paroled into the custody of their better selves … by feeding on hallowed thoughts.” And, “The hermitage of a small, dank cell,” Spector wrote, “if provided with books, can yield a rich harvest of sheer delight and practical values.“‘ (Page 26)

‘Though the prison’s official censor was the associate warden for care and treatment, the actual work fell to Spector. Except for mail, which was read in the cell blocks or the mail room, the senior librarian censored all writings by inmates that left the prison and decided what publications would be purchased for the library.‘ (Page 24)

‘Spector stated his own censorship policy as follows: “Those which emphasise morbid or antisocial attitudes, behaviour, or disrespect for religion or government or other undesirable materials are not purchased.” Like most other librarians of the treatment era, Spector gave little thought to the danger of political, class or cultural bias implicit in his prison censorship policies, and he wasted no time worrying that denying prisoners law books might be unfair or even unconstitutional. Books that gave inmates access to the law were to be confiscated at the gates. Books that criticised church or state were seditious.‘ (Pages 25/26)

It wasn’t only reading that was controlled and owned; writing too:

‘The reduced civil status of prisoners was reaffirmed in 1941 in a section of the penal code titled “Civil Death,” penal code 2600-2601. As a consequence of the Civil Death statute, the California Department of Corrections regarded all writing produced by state prisoners as state property, just as a chair or table made in the prison industries belonged to the state.‘ (Page 25)

Almost constantly throughout his tenure, Spector was at odds with the prison administration who were either unable to grasp, or unwilling to endorse, his aggressive methods of control. When Spector left his post over 25 years of meticulous notes and records were destroyed.

Bibliotherapy and censorship, as Cummin’s concludes, ‘separated prisoners from the power of their own words. Even so, the underlying assumptions of bibliotherapy would soon have a tremendous influence on the lives of certain of the brightest of San Quentin’s inmates, for they would take the notion of reform through reading and writin, the foundation of Herman Spector’s faith, as their own first principle … turning the notion of civil death on its head, reconnecting themsleves to the power of words previously denied them.‘ (Pages 31/32)

Conclusion

Spector’s project founded,at San Quentin, a tradition of literacy that would engender the works of Caryl Chessman, Eldridge Cleaver and the expanded political prison writing movement of the 1970’s. In some ways, the approaches of autodidactism and self determination of the Black Panthers began with the obsessive endeavours of the eccentric biblio-evangelist Herman Spector.

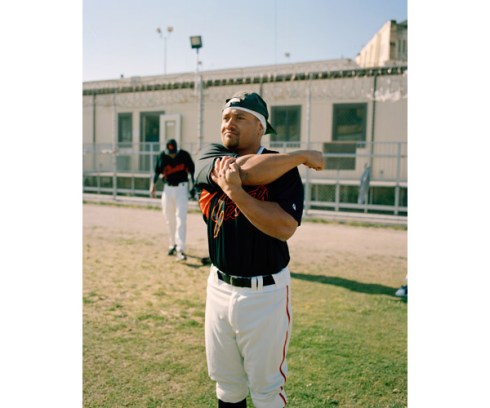

Two months ago I interviewed Emiliano Granado about his experience photographing the San Quentin Giants.

Pitcher for San Quentin Giants. Credit: David Bauman/PE.com

In my research I came upon a lot of media coverage, but I recently unearthed this gem of a slideshow by David Bauman. Enjoy.

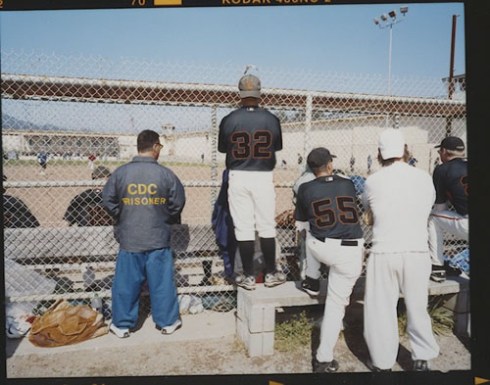

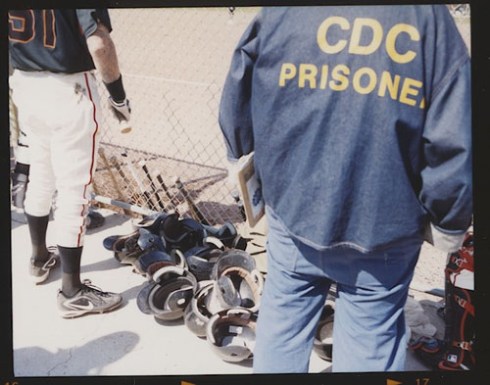

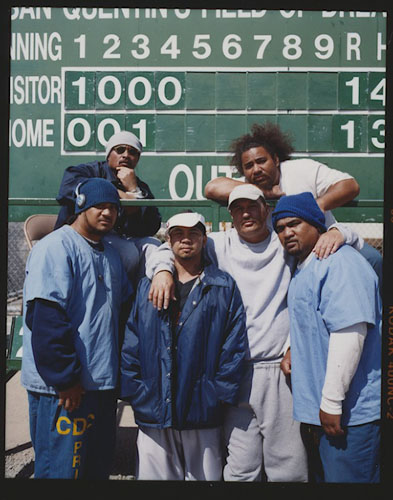

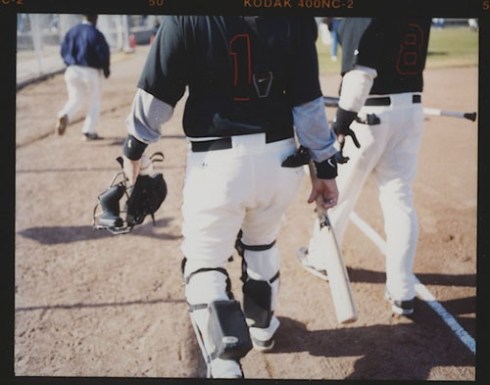

Last week, I threw up a quick post featuring Emiliano Granado’s website images of his photographs of the San Quentin Giants. Here, Granado shares previously unpublished contact sheet images, his experiences and lasting thoughts from working within one of America’s most notorious prisons.

What compelled you to travel across the US to photograph the story at San Quentin?

This was actually a magazine assignment for Mass Appeal Magazine. However, the TOTAL budget was $300, so it really turns out to be a personal project after the film, travel expenses, etc. So, the simple answer to the question is that I’m a photographer. I’m curious by nature. Part of the reason I’m a photographer is to study the world around me. I like to think of myself as a social scientist, except I don’t have any scientific method of measuring things, just a photograph as a document.

With that in mind, it would be crazy of me to NOT go to San Quentin! I’d never been in a correctional institution but I’ve always been fascinated by them. If you look through my Tivo, you’ll see shows like COPS, Locked Up, Gangland, etc. I was also a Psychology major in college and remember being blown away by Zimbardo’s prison experiment and other studies. Basically, it was an opportunity to see in real life a lot of what I’d seen on TV or read in books. And as a bonus, I was allowed to photograph.

What procedures did you need to go through in order to gain access?

I was amazed at the lack of procedure. The writer for the story had been in touch with the San Quentin public relations people, but that was it. There was plenty of other media there that day. It was opening day of the season, so I guess it made for a minor local news story.

I’m pretty sure SQ prides itself in being so open and showcasing what a different approach to “reform” looks like.

It is my opinion that San Quentin is one of the best-equipped prisons in California to deal with a variety of visitors. Did you find this the case?

Definitely. Access was very easy. They barely searched my equipment! Parking was easy. I was really surprised at how easy and smooth the process was. Not to mention there were many other visitors that day (an entire baseball team, more media, local residents playing tennis with inmates, etc).

Did your preparation or process differ due to the unique location?

Definitely. I usually work with a photo assistant and that couldn’t be coordinated, so I was by myself. I packed as lightly as I could and prepared myself for a fast, chaotic shoot. Some shoots are slow and methodical, and others are pure chaos. I knew this would be the latter.

One thing I didn’t think about was my outfit. SQ inmates dress in denim, so visitors aren’t allowed to wear denim. Of course, I was wearing jeans. The officers gave me a pair of green pajama pants. I’m glad they are ready for that kind of situation.

You are not a sports shooter per se. You took portraits of the players and spectators of inmate-spectators. How did you choose when to frame a shot and release the shutter?

Correct. I’m definitely not what most people would consider a sports photographer. I don’t own any of those huge, long lenses. However, I photograph lots of sporting events. I think of them as a microcosm of our society. There are lots of very interesting things happening at events like this. Fanaticism, idolatry, community, etc. Not to mention lots of alcohol and partying – see my Nascar images!

Hitting the shutter isn’t entirely a conscious decision. That decision is informed by years of looking at successful and unsuccessful images. It’s basically a gut instinct. There are times that I search for a particular image in my head, but mostly, it’s about having the camera ready and pointed in the right direction. When something interesting happens you snap.

There are photographers that come to a shoot with the shots in their head already. They produce the images – set people up, set up lighting, etc. Then there are photographers that are working with certain themes or ideas and they come to the location ready to find something that informs those ideas. I’m definitely the latter. There is a looseness and discovery process that I really enjoy when photographing like this. It’s like the scientist crunching numbers and coming to some new discovery.

A lot of photo editors say the story makes the story, not the images. Finding the story is key. Do you think there are many more stories within sites of incarceration waiting to be told?

I’m not sure I agree with that. I always say that a photograph can be made anywhere. Even if there is no story, per se. I definitely agree that a powerful image along with a powerful story is better, but a photograph can be devoid of a story, but be powerful anyway.

Every person, every place, everything has a story. So yes, there are millions of untold stories within sites of incarceration. Hopefully, I’ll be able to tell some of them.

Having had your experience at San Quentin, what other photo essays would you like to see produced that would confirm or extend your impressions of America’s prisons?

Man, there are millions of photos waiting to be made! I’m currently trying to gain access to a local NYC prison to continue my work and discover a bit more about what “Prison” means. Personally, I’d love to see long-term projects about inmates. Something like portraits as new inmates are processed, images while incarcerated, and then see what their life is like after prison. Their families, their victims, etc. And of course, if any photo editor wants to assign something like that, I’d love to shoot it!

Anything you’d like to add to help the reader as they view your San Quentin Baseball photographs?

Yes. When I walked in to the yard, I didn’t know what reaction I would get from the inmates. Everyone was super friendly and willing to be photographed. Everyone wanted to tell me their story. I’m not sure how different their reaction would have been to me if I didn’t have a camera, but I was pleasantly surprised. At first, I felt like an outsider and fearful, but after an hour or so, I felt comfortable and welcome. It was a weird experience to think the guy next to me could be a murderer (and there were, in fact, murderers on the baseball team), and not be afraid. There was this moral relativism thing going on in my head. These people were “bad,” yet they were just normal guys that had made very big mistakes. I left SQ thinking that pretty much any one of us could have ended up like them. Given a different set of circumstances or lack of access to social resources (e.g. education, money, parenting, etc) I could very easily see how my own life could have mirrored their life.

And finally, can you remember the opposition?

I don’t remember who they were playing, but I do remember that their pitcher had played in the Majors and even pitched in a World Series. I believe the article that finally ran in Death + Taxes magazine mentions the opposition.

ALL IMAGES © 2009 EMILIANO GRANADO

Authors note: Huge thanks to Emiliano Granado for his thoughtful responses and honest reflections. It was a pleasure working with you E!

Housekeeping. At the end of my previous post on Emiliano’s work, I postured when San Quentin would get more sports teams for the integration of prisoners and civilians. Emiliano has answered that for me in this interview. He observed locals playing tennis and also states San Quentin also has a basketball team.

With Emiliano‘s permission I have lifted these images straight from his website. We are working together on an interview for a second post on his work (scheduled for next week). It will include previously unpublished and untouched images from his contact sheets. Please stay tuned for that. Meanwhile enjoy my personal selection of six preferred prints.

ALL IMAGES © 2009 EMILIANO GRANADO

_____________________________________________

The San Quentin Giants are well known in the San Francisco Bay Area. I have met a couple of guys in the past who’ve played inside the walls during regular season – it is not unusual.

In an ideal world, the to and fro of public in and out of prison would be without restriction, threat or security protocol. This way, society could fear inmates less and inmates would not be institutionalised to the extent they are today.

I realise this is pie-in-the-sky thinking as the minority of seriously dangerous prisoners necessarily dictate the need for stringent controls. Still it doesn’t mean that increasingly trusted and regular contact between inmate and no-inmate populations cannot be our ideal to shoot for. Smaller and purposefully designed institutions would certainly be the first step in this sea change.

The scheduled games for the San Quentin Giants baseball team are the closest approximation to genuine & normalised interaction between inmate and non-inmate populations. When will San Quentin get a basketball team? Or any other teams for that matter?

____________________________________________

Check out these sources for further information on the San Quentin Giants. Press Enterprise – Long Article and Audio, Mother Jones article – Featuring Granado’s photography, California Connected – Video, Christian Science Monitor – Long article and video, NPR Feature – Audio.

And, if you are really engrossed you can always purchase Bad Boys of Summer, a recent documentary from Loren Mendell and Tiller Russell.

Herman Krieger – stalwart of the Oregon photography community and Eugene resident – is a self-made specialist in the art of captioning. However, more than his quirky words, I appreciate the great lengths he goes to in order to document sites of the prison industrial complex.

View from Boise Gun Club, New Idaho State Prison. Herman Krieger

Krieger described the circumstances of the series, “The idea of making a photo essay on prisons and their settings came after driving from Tucson to Phoenix. The view of the prison in Florence, Arizona struck me as an odd thing in the middle of the landscape. At that time I was only looking at churches for the series, Churches ad hoc“.

With Lifetime Mortgage, Vacaville, California. Herman Krieger

“I then made some photos of prisons in Oregon and California. Others were made during a trip by car from Oregon to New York. I would have made a longer series, but I was too often hassled by prison guards who noticed me pointing a camera at a prison. They claimed that it was illegal to take a photo of the public building from a public road, and threatened to confiscate my film”, explained Krieger.

Room Without a View, Pelican Bay, California. Herman Krieger

Pelican Bay was opened in 1989 and constructed purposefully to hold the most violent offenders, usually gang members. Along with Corcoran State Prison, in the late 1980s, Pelican Bay ushered in a new era of Supermax facilities in California. They are remote (Pelican Bay is just miles from the Oregon border) and they are expansive. Their distant locations prohibit regular visits from inmates’ family members – a detail probably not lost on the CDCR authorities who sought to transfer, contain and stifle the aggressions of Californian urban areas.

Bayside View, San Quentin, California. Herman Krieger

Having lived in San Francisco for three years, the policies, activities, controversies and executions at San Quentin State Prison were always well reported in the Bay Area press. One of the most frustrating repetitions of the San Quentin coverage was the journalist’s compulsion – regardless of the story – to remind readers of the huge land value of San Quentin and the opportunities for real estate on San Quentin Point.

Open for Tourists, Old State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger.

Over the Hill, New State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger

America is a large country. It should be no surprise that prisons are built in isolated areas – it makes economic sense to build on non-agricultural hinterlands and it makes strategic sense to purpose build facilities on flat open ground. More significantly, to locate these “people warehousing units” out of society’s view, allows convenient cultural and political ignorance for the authorities & citizens that sentenced men and women to America’s new breed of prison.

Krieger’s photographs summarise the key intrigues and detachment “we” feel as those excluded from prison operation and experience. Krieger, in some of his other images, gets closer to the prison walls and yet I deliberately featured these six prints precisely because of their disconnect. What terms, other than those of distance and exclusion, can we legitimately use in dialogue about contemporary prisons?