You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Historical’ category.

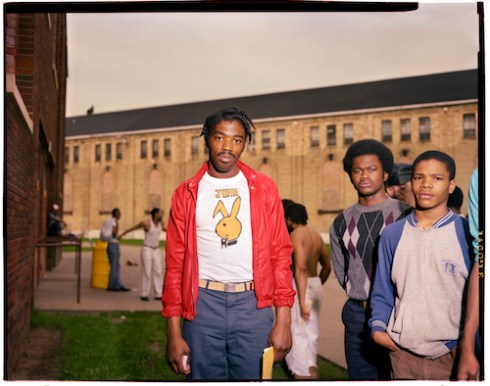

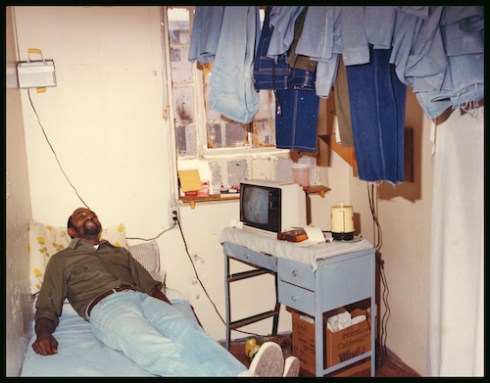

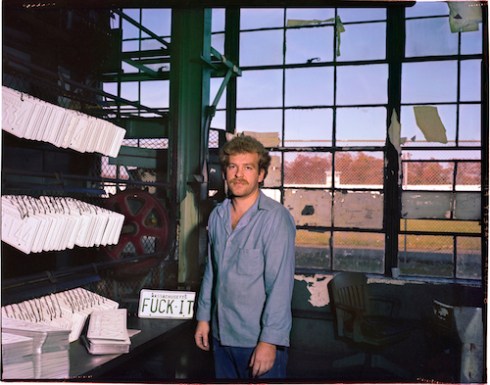

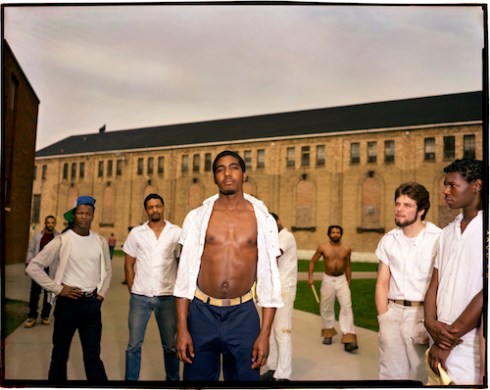

I’ve been stumbling across some mind-blowingly novel prison photographs recently. This incredible Facebook Album by Steve Milanowski fell on my radar and the colour is something special.

Milanowski photographed at three prisons during the eighties — Walpole, Massachusetts (1981, 1982); Ionia, Michigan (1984); and Jackson, Michigan (1985). In 2012, he began shooting the outside of Waupun Correctional Institution in Wisconsin. In each case, Milanowski was working independently and not on assignment.

As colourful and characterful as these images are it’s worth bearing in mind that prisons of this era were beginning to creek. Dangerous overcrowding existed in Michigan prisons in the early eighties, and Jackson in particularly was renowned as a tough prison with gangs and enforced convict codes.

These prison photographs have, up to this point, only had limited circulation. Some feature in Milanowski’s book Duplicity, others on his website. A few photographs have appeared in museum exhibitions around the country. I wanted to know more, so I dropped Steve a line with some questions.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Prison Photography (PP): Where did your interest in prisons come from?

Steve Milanowski (SM): It dates back to my childhood: my dad was an attorney in Michigan and very occasionally had clients that he had to visit in prison. When I was in 5th and 6th grades, maybe twice, he took me along (taking me out of classes) on the prison/client visits. For a 6th grader, these visits were absolutely unforgettable. Indelible. This was an environment that was utterly foreign to my existence. It was almost as if my eyes weren’t fast enough to take it all in. To a kid, nothing in the world looks like a prison.

PP: What was the purpose of your visits the these four prisons?

SM: Simply to make new photographs in places that have mostly been, in the past, photographed with visual cliche and with the perceived grittiness of black and white films.

PP: How did you gain access?

SM: My first permission was with Walpole in Massachusetts. I sent a letter to the Walpole warden; it was written on MIT stationary. I was a graduate student at MIT and I think the name helped in getting me access. I found that once one gets permission to photograph in a prison — that permission leads to more permission. I used the Walpole photographs in gaining access to Jackson and Ionia prisons. No negotiations were needed; they all gave me fairly easy access. Initially, I only asked for single-visit access.

PP: How would you characterize the atmosphere of the prisons?

SM: The atmosphere was taut, tough and difficult at most turns — very regimented and formal. In some instances, I was assigned a female escort which made my shooting more difficult because the inmates had no hesitation in shouting out awful, obscene things; and, the female escorts seemed bent on proving that they were not bothered or intimidated by these nasty shout-outs.

PP: How does this body of work relate to your other projects and your philosophy/approach to photography generally?

SM: I consider my work to be the work of a portraitist. My prison portraits are stylistically in line with the portrait work that I pursue “out in public” at public demonstrations, holiday parades, festivals, fairs, and competitions.

PP: What were the reactions of the staff to your photography?

SM: I never really sought out their reactions. My photographs did seem to always successfully get me more access though.

PP: What were the reactions of the prisoners?

SM: Never really got reactions, per se. But with each portrait, I offered a free print if they wrote me a request and visually described themselves; some inmates wrote back and praised the images. Some seemed to want to start a pen pal relationship, just because, it seemed, some inmates had few contacts with the outside world.

PP: What is your personal opinion of prisons? Have they changed since you visited in the eighties?

SM: Prisons, then and now, in America, seem to continue to be warehouses; I think most Americans are aware of the fact that we, as a nation, have one of the largest prison populations in the world — and that we incarcerate at a level that far exceeds almost all other nations.

Have prisons changed? One change I’ve noticed with great concern is the concept and use of Supermax prisons which seems to be uniquely American. With older prisons as well as Supermax prisons, we seem to never be willing to spend much money on reducing recidivism.

The conservative right loves to convey the idea that they are tough on crime — tough prisons, tough sentencing, and the idea of “throw away the key.” So, our prison populations grow, and we build more prisons than any other nation. We’ve seen the expansion. And the Democrats? They do their best to avoid being tagged as “soft on crime.”

PP: What are Americans’ feeling toward crime and punishment?

SM: Americans very much ignore prisons and prison life — unless they live near a prison where the prison is the source of some level of local employment. Americans seem to only take notice of prisons when there is a problem, an escape, a prison disturbance (that receives national media attention), or when there is some breakdown in the system.

There seems to be a real void in political or community leadership especially in the realm of education as a path to reducing crime and reducing prison populations; the idea gets plenty of lip service.

PP: What role has photography in telling publics about prisons? Is it an effective tool?

SM: I think photography can help — and be an effective tool in informing the public about prisons and who inhabits American prisons; but, I’m not sure at all that our society wants to look at prisons and prison life … its too easy to ignore.

PP: What camera and film did you use?

SM: 4×5 Linhof and 4×5 Kodak and Fuji color negative. Sometimes a Pentax 6×7 with Fuji and Kodak color negative film. And, always combining flash with ambient light.

PP: The color you introduce is unusual for prison photographs. From looking at your other work, it is clear you revel in colour portraits. Were you aware that you were making unique images; splashing color all over these darkened corners of US society?

SM: Unique images? Well you have hit on something that was a primary intention: I wanted to make photographs that told you something new. Pictures you hadn’t seen before. Prison photography is rife with cliches. I thought if I were given access to prisons, I’d make different photographs. I was not arrogant about this — just determined to make images that had not been seen before.

I was determined, self-directed and wanted to get as many photographs as I could accomplish in, typically, a 1 to 2 hour visit. I limited my talk and conversations — I was on a mission.

BIOGRAPHY

Steve Milanowski is a photographer and, with Bob Tarte, co-author of Duplicity, a monograph of his own portraits. Milanowski earned his BFA from The Cranbrook Academy of Art and his MS from The Creative Photography Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His photographs are part of the permanent collections of The Museum of Modern Art, National Gallery of Art, The Houstin Museum of Fine Arts, The High Museum of Art, and The Polaroid Collection and numerous public collections. MoMA published his work in Celebrations and Animals; his work was also included in MoMA’s recent survey of late 20th century photography in the newly reinstalled Edward Steichen galleries.

Photo: Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange

In 1981, freelance photographer Karen Ruckman stepped inside the notorious medium-security Lorton Prison to teach prisoners photography. Lorton was a sprawling barrack-like institution nestled in a rural pocket of the Virginia suburbs. Lorton, a Federal facility, closed in 2001. For decades it was where Washington D.C. sent its convicted felons. Initially, the administration didn’t think the program would last more than a few sessions and the students were cautious. Ruckman successfully won grants, donations from Kodak, cash from private donors, and support from then Mayor’s wife Effi Barry to support the photography workshops. Ruckman taught at Lorton until 1988.

When I recently learnt about Ruckman’s work, I was floored. For the longest time I have said that photography workshops inside of American mens prisons ended in the late seventies and mass incarceration had precluded the mere chance. Ruckman’s work at Lorton has forced me to reevaluate my timeline. I hope Ruckman’s work also brings you encouragement.

In 1985, Ruckman invited cameraman Gary Keith Griffin to film the class at work. Now, she and Griffin are working on a documentary about this unique moment in prison arts education. Ruckman and Griffin have followed some of the men since their release and the film, tentatively titled InsideOut, is slated for release in 2015 — the 30 years after Gary made those first reels.

Ruckman has routinely worked with populations considered to have less of a voice in our society – battered women, the poor, and at -risk youth for example. She also taught photography in the D.C. women’s jail, but that single summer program doesn’t feature in the film.

Karen Ruckman and I spoke about her access, the program’s successes and obstacles, the need for diverse image-makers in criminal justice and the lessons the project contains for us all three decades on.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

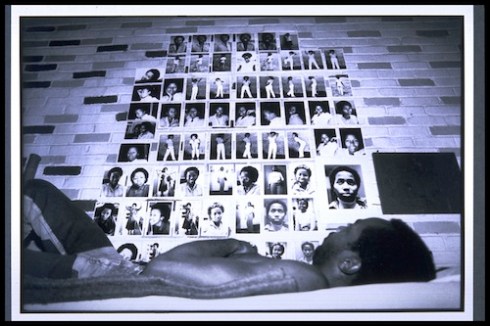

Photo: Calvin Gorman. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Calvin Gorham

Q&A

Prison Photography (PP): I wasn’t aware of any prison photography workshop programs after the 70’s and so to find your work at Lorton is a revelation. It’s 25 years since the program ended, so let’s start with the basics, how did you get involved? Where did the idea come from?

Karen Ruckman (KR): I was doing work for the Volunteer Clearinghouse here in D.C. and they sent me to the prison to photograph volunteers who were tutoring inmates. I went to Lorton with George Strawn, the head of volunteer services and he asked if I’d be interested in teaching a class. I hadn’t really thought about it, but it happened to coincide with the funding for proposals coming in to the D.C. Arts Commission and I applied for a career development grant and I got it, much to my surprise.

I went down once a week and taught photography with a focus on career development. I approached it as a basic photography class and I brought in guest speakers, photographers from various newspapers, friends of mine in the community who were photographers. It went very well. The men worked hard, so after that I applied for another grant. Actually, D.C. had a category called ‘Arts in Prison’ during the 80s. I got my later funding through that grant category.

PP: Which photographers visited the class?

KR: Craig Herndon, from the Washington Post; Bernie Boston, from The Los Angeles Times, Gary Keith Griffin who works primarily in video and is working with me on the feature documentary now. I had executives from NBC who came in too, as well as local artists and fine arts photographers.

PP: What other arts program were being taught in D.C. prisons at the time?

KR: There were several theater programs and a woman who taught painting. That’s pretty much it.

Photo: Bernard Seaborn. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Bernard Seaborn

PP: How did the program develop over the 8 years? Did the funding, scope or size of the class change?

KR: I had a cap on how many students I could have but I ended up doing two classes. Prisoners who had been in the earlier classes then became mentors to the new guys. Over time, I became more of a facilitator: bringing in supplies, bringing in expertise, working with them, training them and then they took on the job of mentoring each other.

They also ran the dark room when I wasn’t there. We built a dark room in a closet that was in the prison school where classes took place. I had a teaching assistant, Chuck Kennedy, who came with me from the community but I also had a prisoner who was a teaching assistant so the guys could work during the week. The program grew with more men participating, more prisoners developed skills. The inmates took on more of a teaching role; it was always my goal that they would.

PP: How many students would you say you taught over the seven years?

KR: I tried to figure this out once some years ago! More than 100 but less than 200. We had new intakes for each class and some guys stayed in year after year. They’d been charged for felonies in D.C. Some had written bad checks, others had been charged for murder.

PP: Lorton is now closed?

KR: It was closed in 2001. It was a rather controversial move. The prison was actually located in Virginia on hundreds of acres of land. There were different facilities there including two youth centers, Central, the medium security facility where I taught, and maximum. Virginia had been wanting that land for quite some time.

Lorton’s buildings needed a lot of work, and rather than renovate, they closed it. The Federal government transferred the land to Virginia and now D.C. prisoners are farmed out across all of the country.

PP: Ouch! That can’t be good for rehabilitation.

KR: It’s terrible, yes. And so there’s no programing, and they’re in federal facilities all over the country.

Photo: Sidney Davis. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Sidney Davis

PP: What was the reaction and the response from the prison authority? Today, of course, these programs don’t exist and often the language-of-security is used to deny all sorts of things within prisons, and the camera in particular is quickly labelled as a security hazard. What was the feelings of the Lorton authorities at that time?

KR: I had to take on the job of educator. Many didn’t understood the need for the men to go outside the classroom to photograph, and the usefulness of exhibitions. They understood the photo class but part of that, part of each class was doing a show. We always did one in the community and one in the prison — it was a massive job of educating staff about how we could go about producing the program successfully.

I was very fortunate because Effi Barry, the mayor’s wife, had just opened an art gallery and I had her support. I always went top down. It took me a lot of time to go through the necessary channels and to get the permissions. The administrator at Central Facility, Salanda Whitfield, was a really nice guy who supported the program. He died some years ago.

Mr. Whitfield let the program come in, he let us break the rules, because of course cameras weren’t allowed, and of course inmates were not allowed to take photographs. Even with his backing I still had lots of paperwork to do in order to make the classes function well.

I found some resistance from the guards who felt like the inmates were getting something that was too nice, that wasn’t fair, that they shouldn’t get. So, my real problem when I had problems was always from the guards.

Photo: Michael Moses El. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Michael Moses El

Photo: Calvin Gorman. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Calvin Gorham

PP: Before you began the project, did you consider yourself an activist in that field of criminal justice?

KR: No, I was an activist generally but not particularly in prison reform.

PP: Did you ever have visitors that were inspired by the program and wanted to replicate it elsewhere? Or were you working in a bubble?

KR: I guess I worked in a bubble. I mean, I had visitors and help from others. I had photographers come in, other artists as well, but, no, I didn’t have anyone that wanted to replicate it.

PP: Did you understand at the time that you were doing something very pioneering?

KR: I don’t think so. I mean it was a really interesting time. Many of us were doing things in the community and were trying to think sideways, and I felt like it was something exciting. I had a passion about taking the camera to people who couldn’t normally tell their stories. By giving the men in my program this powerful communication tool, it was an opportunity for them to tell people who they were, it was a humanizing agent.

For the documentary, and since 2001, we’ve followed up with two of the men who were in Lorton and the program.

Michael Moses El had a fascination with guns. He found that when he came into the program that he was able to transfer this fascination with guns to the camera. It was a very exciting thing for him.

Calvin Gorham is an artist. He’s a singer; a soulful person and he used photography as an artistic tool to communicate how he felt. He said he saw a lot of dark things in the prison and he photographed to express that.

PP: And so there’s no doubt in your mind that photography is a rehabilitative tool?

KR: It’s a powerful rehabilitative tool. There are so many levels one could do with it as a storytelling device. Now, with digital imaging, possibilities are unlimited. Yes, absolutely. I worked with other groups in the city. In 1988, I also worked with women at D.C. Jail, then in the 90s with women at a pre-release halfway house. Also, women in various shelters and at-risk kids.

PP: And so tell us about the documentary, it’s been thirty years since you’ve been doing this work, how and why did you decide a documentary was necessary?

KR: In 1985, Gary Griffin, a friend and colleague, bought his first TV camera. Gary thought it would be valuable if we could do video about the program. So I got permission again, days of paperwork, but we went in with a crew for a week in 1985.

Some of the footage in the trailer is from ’85. We never were quite sure what it was going to be. We did put together a fundraising piece because I was always having to raise money.

Photo: Michael Moses El. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Michael Moses El

PP: Right, you were constantly communicating with free society how important your work was and asking for help?

KR: To do the programing, I had to constantly write proposals and fundraise. I was somewhat burnt out by the end of the 80s. The funding for the prison program became very difficult to get. I went on to work with other groups and do different things. The guys would stay in touch with me, they had my business phone and they’d call me when they got out of prison and tell me what they were up to.

But, I still have the wonderful images. I was at a workshop in Santa Fe in the late 90s and showed some of the images to National Geographic photographer Sam Abell. I also had an audio tape from one of the graduations that I put with the images and it was a very powerful slideshow (of sorts) — one of the men at one of the graduations gave a marvelous speech about photography.

Sam was excited by the images and very supportive. He said. “You’ve got to do something with this.”

I decided along with my video production friends to do a reunion. We knew Lorton was closing. I tracked down as many of the guys as I could. We had about 20-25 at the reunion. Gary documented the reunion and then we documented some of the men periodically. We later settled on following Michael and Calvin.

Photo: Calvin Gorman. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Calvin Gorham

PP: Why Michael and Calvin?

KR: Number 1, they were interested in participating. Number 2, they’re very interesting people — Michael is business-oriented, very focused about his life. Calvin’s a musician, we have a lot of footage of him singing. We’ve seen them almost every year since 2001. Gary and I think 30 years is a good amount of time. When we get this feature documentary completed by 2015 it will have been 30 years since Gary began filming.

PP: The documentary is a few things, it seems? A record of a moment; the on-going stories of Michael and Calvin; and a call to action asking people to think about photography’s relationship to educational and rehabilitation?

KR: It is. It’s a character study that presents the power of photography, the power of art, and how important both can be in changing lives.

Only a few of the men now make pictures professionally, but they all make pictures still. The documentary is about the program and how the learning experience has stayed with the participants throughout their lives; how it continues to resonate and define their world view in a positive and powerful way.

The discipline required working in the dark room was critical. For example, one participant, David, spent two years learning how to make a good print. And he ultimately made beautiful prints. Two years. It was very impactful.

Photo: David Mitchell El. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + David Mitchell El

PP: Can you give us your thoughts of storytelling, self-representation and empowerment?

KR: It was always their story to tell. I came in, I gave them cameras. I didn’t take a lot of pictures. I was there as a facilitator. I gave them the tool to tell their stories. I think that’s enormously important.

During that period — and even now — there’s something that is bothersome to me when people go in and take pictures of powerless people. It’s important for people to tell their own story; that doesn’t just shift the viewer, it shifts the person telling the story.

PP: It does seem obvious that if one puts a camera into the hands of someone in the community that you’re trying to bring new information about and to the wider world, but there’s still so many people in the photo world who reject that.

KR: Yes. This is off topic, but probably the most amazing experience I had when I took exhibitions to the community was when I hung a show by women at a shelter for victim’s of domestic violence. We did a show of their work at the D.C. library, in the mid-90s. Visitors would ask me who took the photographs, and when I explained the women photographers were survivors of domestic violence, people would just stop and walk out of the room.

How do we relate to issues that we’re uncomfortable about? Do we not want to see these individuals?

PP: Well, what were attitudes like then about crime? What was the reputation of Lorton? What was the general community’s view of Lorton prison?

KR: Lorton and the D.C. community were very connected in the eighties. So many people from the city were incarcerated there that Lorton was just like a subset of the community. So, there wasn’t as much stigma with prisoners as I encountered among other groups that I worked with, at least in D.C. at that time.

Lorton was considered a very dangerous place. The facilities were old even when I was there. The men lived in dorms and there was one guard per dorm at night so you can imagine that there was some violence. I personally, I didn’t get too involved in that. I tried to go in and do my program with them without judgement.

Photo: Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange

PP: And then tell me about the dark room? Were there any issues with taking chemicals and other apparatus in?

KR: The dark room was fabulous! I brought the supplies and the men ran the dark room. Kodak gave me film and photographic paper. I bought chemicals. We had lots of applicants, but I could only take so many, so it was considered a reward for someone to get into the photography program.

PP: On what criteria did you decide admission?

KR: They had to have good behavior to be allowed in the program. When it started out I only admitted men that were within three years of parole because the lessons were about career development; it was my hope to actually help guys get jobs once they got out. After a while, we relaxed that rule and a few guys still had a lot of time to serve.

PP: And could students be removed from the program at the whim of the warden or the staff?

KR: Well, I lost a few people because they misbehaved in prison and were sent to the hole (solitary confinement), or to another prison. That happened.

PP: When you release the documentary have you got any plans for distribution. How do you plan to reach audiences?

KR: I’m taking that a step at a time. We are going to finish a 30-minute short this winter that we’ll take to film festivals. A local organization, Docs In Progress, is hosting a showing of the trailer. I’ll contact our local PBS station, but with the feature-length film I have to plan a more structured distribution plan. It’s very important to get it out. I’ve stayed in connection with people in the D.C. community, people like Marc Mauer at the Sentencing Project and others who care about the issue.

PP: What’s your personal position on prisons? What role does incarceration play in our society?

KR: There are people who commit violent crimes and they belong in prison. Some of the men that I worked with said that being in prison gave them an opportunity to really look at themselves and take a timeout and to correct their behavior. There is a role for prison if they have rehabilitation programs.

Of course, we all know that there are way too many people that are incarcerated and there are people that are incarcerated that just shouldn’t be there, so it’s very frustrating. Things haven’t changed all that much since the eighties except we’ve incarcerated more people.

D.C. incarcerates an enormous number of people. With the poverty and lack of good public education here. That’s the story of the documentary. Calvin’s son went to prison and Michael’s son went to prison. So, we talk about that story, it’s that legacy that’s just, it should be broken. Marian Wright Edelman‘s work with the Children’s Defense Fund deals with this issue, and has a program called the Cradle to Prison Pipeline.

Photo: Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange

PP: Do you think the American public gets reliable information on prisons?

It’s my sense that most people aren’t interested in prisons. When I tried to raise money for the program it was very hard. There’s little compassion. Around drugs and drug culture there’s some alternative sentencing programs happening but by and large, I don’t think people are interested. I mean, now, we have for-profit prisons which is even more atrocious because now we have to maintain the population so that profit lines can be maintained.

PP: I ask because, to my mind, if there were more photography programs like yours occurring in our prisons today, there would exist a more nuanced view of prisons; prisoners’ views. We’d all be in a better place in terms of being informed.

KR: Yes, absolutely. The program had a humanizing effect, both on the participants and in how they were viewed by the community. It provided a bridge, and it didn’t cost the tax payers much. I secured small grants and fundraised and so it was for tax payers a really good deal. That’s true of most arts programming.

PP: Often program funding is based on measurable impacts but a lot of time with prisons you can’t measure those so easily because some people are not getting out for ten or twenty years. You can’t correlate arts rehabilitation with recidivism because the prisoners don’t get out in any short space of time. So, what stories do you have about your students? Any stand out stories that convince you of the efficacy of a photography program?

KR: The men would be the ones to tell you. Sadly, a lot of the guys die; they don’t make it. Some of them die soon after they get out.

I think about Calvin and Michael — the program gave them discipline and an opportunity to evolve productively. Michael told us about a time soon after his release when he was very tempted to commit a violent act against another man. Something stopped him. It was, he said, it was the discipline and working relationships that he had developed during the program. He didn’t want to end up back at Lorton.

A couple of the guys do a lot of professional photography. It’s very hard to answer that question because people want to ask, “Okay, well how many guys got a job as a photographer?”

PP: How many people generally get jobs as photographers!

KR: Actually, Michael was hired by US News and World Report to shoot a cover story on poverty, and he took some amazing pictures. They were going to use one of his photos for the cover but when they found out he was an ex-offender they wouldn’t run his photo. He’s still very bitter about that.

PP: What’s his past history got to do with the suitability of a photograph?

KR: It was many years ago; it was the late 80s.

PP: But that’s complete discrimination.

KR: I was told by several photographers at the Post that they would be uncomfortable to have ex-offenders there because they would be afraid that they would steal equipment. These are the attitudes that make it really tough for ex-offenders to get jobs in fields other than construction or the food industry, though a few of them do get jobs driving Metro buses.

PP: Is there anything I’ve missed?

KR: I appreciate you finding and highlighting the work. We’re excited about finishing the film. The project has ended up — without me realizing it — a life work.

FOLLOW

You can follow Karen and Gary’s development of the film via the InsideOut website, on its Facebook page, Tumblr page and via Karen’s Twitter.

TRAILER

“The U.S holds more prisoners and employs more prison staff than any other nation on earth. But there is no central location where the public, policy makers, students or researchers can benefit from the many years of first-hand experience of prisoners and prison workers,” read the email that landed in my inbox last week.

The American Prison Writing Archive (APWA) is an in-progress, internet-based, digital archive of non-fiction essays recently established by the Digital Humanities Initiative at Hamilton College, Clinton, New York.

APWA addresses a need and it could be of immeasurable value. It’s early days; the archive has yet to fill. Digital storage provides an almost limitless potential for growth. The accumulation of material is also without deadline.

Sure, there are many great places such as the PEN American Center, The Beat Within, Prison Legal News, The Angolite, San Quentin News, Prison Writing blog, where one can find expert prison writing, but how much of this is searchable by key terms? On what page of a Google search does it land? There’s so much good but untapped writing on prisons out there that to have a feasible search tool (designed by library-scientists) is very exciting.

FROM THE SOURCE

“We seek authors who write with the authority that only first-person experience can bring,” says APWA about it’s one parameter for submissions. I think that insistence gives the project weight and legitimacy.

While the APWA is open to all styles, they encourage first hand accounts from prisoners, prison employees, and prison volunteers of life and work conditions within American prisons.

Often prisoners and prison employees are in opposition, but with submissions from both groups who knows what cross-pollination of perspectives might emerge?

From here, I’ll leave you with APWA’s own description of the project:

All topics are of interest, including descriptions of sources of stress, ways of coping, health care, causes of violence and ways to reduce violence, material conditions, education, employment conditions and the challenges these conditions present, the environment for volunteers, the aging prison population, visions of a better way to operate (personally, politically, institutionally, etc.), reflections on the work of dealing with time inside (for workers as well as prisoners), the challenges of physical and psychological survival, public perception and popular depictions of prisoners and prison workers, the politics and economics of mass incarceration, what works and why it works, and what doesn’t work and why it doesn’t work (i.e. practical views on reform), etc. We are open to any testimony about the issues that matter to prison staff, administrators, corrections officers, teachers, volunteers, and prisoners.

We value writing that takes thoughtful, constructive positions even on passionately felt ideas.

The APWA is intended for researchers and for the general public, to help them understand American prison conditions and the prison’s practical effects and place in society. All the work in the APWA will be accessible to anyone, anywhere in the world with access to the Internet. The APWA will open the American prison to public observation, and showcase the thinking and writing being produced inside.

Once included in the APWA, work will be retained indefinitely. Contributors can write under pseudonyms or anonymously. We reserve the right to edit or reject work that advocates violence, names names in ongoing legal cases, or libels named individuals. The APWA is not currently accepting poetry or fiction.

We accept art (on a single 8.5×11 page) only if accompanied by an essay. A signed permission sheet must be included to post work on the APWA. By signing on the signature line below, you are granting us permission to include your work in the APWA. The questionnaire information will be used to offer researchers points of reference (for example, to study the specific concerns of staff who are veterans, or of Black and Latino men in maximum-security facilities).

There is no deadline. We seek the widest possible gathering of American prison writing, and we will read, scan, and transcribe essays into the APWA on a continuing basis. Previously published work is acceptable if authors retain copyright. Please let us know where and when your essay appeared in print.

Non-fiction essays, based on first-hand experience, should be limited to 5,000 words (15 double-spaced pages). Clearly hand-written pages are welcome. We charge no fees. We will read all writing submitted.

There is a PDF form to submit with your essay. It includes the usual stuff — name, age, address, date, prison facility. It also includes an optional questionnaire to help the archivists digitally tag and organise essays.

Please share the project, the link, and the address below far and wide.

Mail essays to: APWA, 198 College Hill Road, Clinton, NY 13323.

Elainaise Mervil. Source: The Tallahassee Project via VICE

I was recently speaking with an advocate who visited women’s prisons in California to learn about their circumstances and build cases for release. She said to me, “There needs to be more media in prisons. The women with whom I have conversations totally complicate peoples’ ideas about who a criminal is.”

Unquestionably, photographic media plays a role in telling stories. Some photographs better than others. If storytelling is about connection and about empathy, then what better photographs than the family snap or the amateur portrait?

This week, the unavoidable ordinariness of prisoners’ portraits was in evidence on VICE.

Jamie Lee Curtis Taete did us the service of republishing images from the book The Tallahassee Project: One Hundred Prisoners Of The War On Drugs, by John Beresford, M.D.

“The majority of the women shown in the book were charged with ‘conspiracy’ based on the statements of informants who spoke to authorities in exchange for reduced sentences,” says Curtis Taete.

From a woman whose old phone, still in her name, was used by a drug dealer to a women who drove drugs across state lines. Yes, there may have been a poor decision or lack of inquiry involved but there was also coercion (usually by a male friend or family member) and the result is a long, long mandatory-minimum sentence. Such is the War On Drugs which has been largely responsible for an eightfold increase in the female prison population in the U.S.

It’s likely many women implicated in drugs investigations are mere runners and may not even possess the information needed to bargain with the authorities. The result is destroyed families and ruined lives. 16 years, 24 years and even life for a failure to cooperate with authorities. How do these numbers even make sense? They don’t. They are shameful.

Below, I include a particularly insightful contribution to The Tallahassee Project book [my underlining] by Elainaise Mervil (pictured above).

Inmate ID Number: 20982-018

Sentenced to 20 years for conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute cocaine base and cocaine hydrochloride .

Estimated release date: 08-07-2014

I am a Haitian lady who has left 4 minor children behind to do this mandatory sentence. I have no criminal history. I am a first-time non-violent offender. It seems the government is tearing families apart and the children are the ones that are really made to suffer for this “War on Drugs.” P.O.W.

I fell into the wrong crowd in Orlando, Florida. I have never had any problems with the law and only am now learning to read and write the English language. I am a native of the beautiful country of Haiti. I love America, but I believe that the judicial system needs some change and review.

Conspiracy is such an all-encompassing category that if no other charge may be brought forth, one is charged with conspiracy and subjected to the 10-year mandatory minimums which increase rapidly in direct proportion to hearsay evidence whether true or not true. It appears that a person who is found in possession of narcotics will receive less time than a person who was not found in possession of anything, since conspiracy seems like the only viable charge.

Conspiracy was originally designed to target “king pins” who are usually sheltered by runners, etc. But what has happened instead is that the king pins are the ones who receive the most favorable deals since they have the most to provide to the government for substantial assistance motions as they possess many many contacts. The “little man” who does not know as much suffers since his assistance is not as valuable; hence, falling victim to the harsh treatment under the law by being required to serve a decade-plus in prison.

I applaud this use of photography. Let’s see more activists and journalists in prisons gathering such image and word to amplify the voices of those callously thrown away by our society.

–

UPDATE, 05/14/2013: Harpers Books confirmed that the collection was bought by an individual at Paris Photo LA.

–

At Paris Photo: Los Angeles, this week, a collection of California prison polaroids were on display and up for sale. The asking price? $45,000.

The price-tag is remarkable, but so too is the collection’s journey from street fair obscurity to the prestigious international art fair. It is a journey that took only two years.

The seller at Paris Photo LA, Harper’s Books named the anonymous and previously unheard-of collection The Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive. Harper’s has since removed the item from its website, but you can view a cached version here. The removal of the item leads me too presume that it has sold. Whether that is the case or not, my intent here is not to speculate on the current price but on the trail of sales that landed the vernacular prison photos in a glass case for the eyes and consideration of the photo art world.

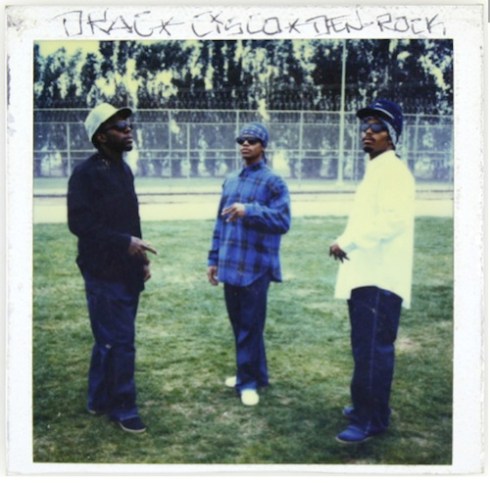

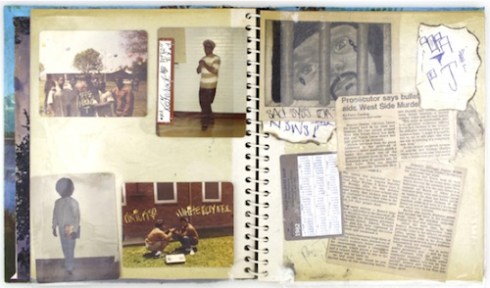

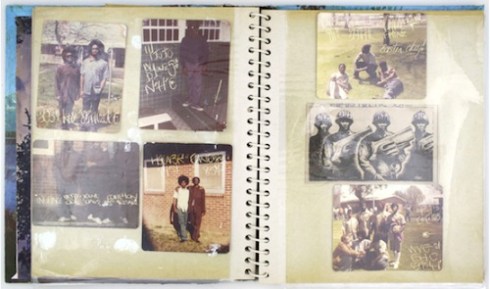

The Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive on display at Paris Photo LA in April, 2013.

FROM OBSCURITY TO COVETED FINE ART COMMODITY

In Spring 2012, I walked into Ampersand Gallery and Fine Books in NE Portland and introduced myself to owner Myles Haselhorst. Soon after hearing my interest in prison photographs, he mentioned a collection of prison polaroids from California he had recently acquired.

You guessed it. The same collection. Where did Myles acquire it and how did it get to Paris Photo LA?

“I bought the collection from a postcard dealer at the Portland Postcard Show, which at the time was in a gymnasium at the Oregon Army National Guard on NE 33rd,” says Haselhorst of the purchase in February, 2011.

As the postcard dealer trades at shows up and down the west coast, Haselhorst presumes that dealer had picked up the collection in Southern California.

Haselhorst paid a low four figure sum for the collection – which includes two photo albums and numerous loose snapshots totaling over 400 images.

“I thought the collection was both culturally and monetarily valuable,” says Haselhorst. “At the time, individual photos like these were selling on eBay for as much as $30 each, often times more. I bought them with the intention of possibly publishing a book or making an exhibition of some kind.”

Indeed, Haselhorst and I discussed sitting down with the polaroids, leafing through them, and beginning research. As I have noted before, prison polaroids are emerging online. I suspect this reflects a fraction of a fledgling market for contemporary prison snapshots. Not all dealers bother – or need to bother – scanning their sale items.

Haselhorst and I were busy with other ventures and never made the appointment to look over the material.

“In the end, I didn’t really know what I could add to the story,” says Haselhorst. “And, I didn’t want to exploit the images by publishing them.”

Another typical and lucrative way to exploit the images would have been to break up the collection and sell them as single lots through eBay or at fairs, but Haselhorst always thought more of the collection then the valuation he had estimated.

In January 2013, Haselhorst sold the collection in one lot to another Portland dealer, oddly enough, at the Printed Matter LA Art Book Fair.

“Ultimately, after sitting on them for more than two years, I decided they would be a perfect fit for the fair, not only because it was in LA, but also because the fair offers an unmatched cross section of visual printed matter. It was hard putting a price on the collection, but I sold them for a number well below the $45,000 mark,” he says.

Haselhorst made double the amount that he’d paid for them.

The second dealer, who purchased them from Haselhorst, quickly flipped the collection and sold it at the San Francisco Antiquarian Book Fair for an undisclosed number. The third buyer, also a dealer, had them priced at $25,000 at the recent New York Antiquarian Book Fair.

From these figures, we should estimate that Harper’s likely paid around $20,000 for the collection.

Harper’s Books’ brief description (and interpretation) of the collection reads:

Taken between 1977 and 1993. By far the largest vernacular archive of its kind we’ve seen, valuable for the insight it provides into Los Angeles gang, prison, and rap cultures. The first photo album contains 96 Polaroid photographs, many of which have been tagged (some in ink, others with the tag etched directly into the emulsion) by a wide swath of Los Angeles gang members. Most of the photos are of prisoners, with the majority of subjects flashing gang signs.

[…]

The second album has 44 photos and images from car magazines appropriated to make endpapers; the “frontispiece” image is of a late 30s-early 40s African-American woman, apparently the album-creator’s mother, captioned “Moms No. 1. With a Bullet for All Seasons.”

[…]

In addition, 170 loose color snapshots and 100 loose color Polaroids dating from 1977 through the early 1990s.

In my opinion, the little distinction Harper’s makes between gang culture and rap music culture is offensive. The two are not synonymous. This is an important and larger discussion, but not one to follow here in this article.

HOW SIGNIFICANT A COLLECTION IS THIS?

Harper’s is right on one thing. The newly named ‘Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive’ is a unique collection. Never before have I seen a collection this large. Visually, the text etched directly into the emulsion is a captivating feature of many of the polaroids.

We have seen plenty of vernacular prison photographs from the 19th and early to mid 20th century hit the market. Recently, a collection of 710 mugshots from the San Francisco Police Department made in the 1920’s sold twice within short-shrift. First for $2,150 in Portland, OR and then for $31,000 in New York just four months later! At the time of the sale, AntiqueTrader.com suggested it “may [have] set new record for album of vernacular photography.”

As a quick aside, and for the purposes of thinking out loud, might it be that polaroids that reference Southern California African American prison culture are – in the eyes of collectors and cultural-speculators – as exotic, distant and mysterious as sepia mugshots of last century? How does thirty years differ to one hundred when it comes to mythologising marginalised peoples? Does the elevation of gang ephemera from the gutter to traded high art mean anything? I argue, the market has found a ripe and right time to romanticise the mid-eighties and in particular real-life figures from the era that resemble the stereotypes of popular culture. It is in some ways a distasteful exploitation of people after-the-fact. Perhaps?

WHERE DOES THE $45,000 PRICE-TAG COME FROM?

Just because the so-called ‘Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive’ is rare, doesn’t mean similar collections do not exist, it may just mean they have not hit the market. This is, I argue, because no market exists … until now.

If the price tag seems crazy, it’s because it is. But consider this: one of the main guiding factors for valuations of art is previous sales of similar items. However, in the case of prison polaroids, there is no real discernible market. Harper’s is making the market, so they can name their price.

“All in all, it’s pretty crazy,” says Haselhorst, “especially when you think about how I bought it here in Portland over on 33rd, just a few miles from our gallery.”

All these details probably make up only the second chapter of this object’s biography. The first chapter was their making and ownership by the people in the photographs. Later chapters will be many. Time will tell whether later chapters will be attached to astronomical figures.

Harper’s suggests that rich “narrative arcs might be uncovered by careful research.” I agree. And these are importatn chapters to be written too.

I hope that more of these types of images with their narratives will emerge. If these types of vernacular prison images are to command larger and larger figures in the future, I hope that those who made them and are depiction therein make the sales and make the cash.

As it stands the speculation and rapid price increases, can be interpreted as easily as crass appropriation as it can connoisseurship. If these images deserve a $45,000 price tag, they deserve a vast amount of research to uncover the stories behind them. Who knows if the (presumed) new owner has the intent or access to the research resources required?

Along that same vein, here we identify a difference between the art market and the preservationists; between free trade capitalism and the efforts of museums, historians and academics; between those that trade rare items and those that are best equipped to do the research on rare items.

Whether speculative or accurate, the $45,000 price is way beyond the reach of museums. Photography and art dealers who are limber by comparison to large, immobile museums are working the front lines of preservation.

“Some might say that selling [images such as these] is exploitation, but a dealer’s willingness to monotize something like this is one form of cultural preservation,” argues Haselhorst. “If I had not been in a position to both see the collection’s significance and commodify it, albeit well below the final $45,000 mark, these photographs could have easily ended up in the trash.”

Loose Polaroids from the Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive as displayed by Harper’s Books at Paris Photo LA, Los Angeles, April, 2013.

A cover to one of the two albums that make up the Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive.

“I imagined you’ve seen lots of prison everything so it’s a bit intimidating to send you anything for fear I’m just repeating,” said the anonymous tip off in my inbox. The link was to a film entirely new to me. It blew me away and will you too.

Jonathan Borofsky, famous in recent years for a bunch of monstrous sculptures of 2-D men (usually hammering the air), made Prisoners in 1985. It’s one of the best prison films I’ve seen, mainly because Prisoners doesn’t weave too persistently one particular tale or one particular journey. To be reductive, I’d argue that this is the unique artist’s treatment of the subject in stark contrast to the straight documentarian’s treatment.

Generally, prison documentaries are often about trial and adversity; they necessarily have to depict struggle and hope from all angles. In other words, documentaries are often part-advocacy and answers. Borofsky just had questions. The answers the 32 California prisoners had for him in interviews will stay with you.

Part horror testimony, part philosophy, part confession, part therapy, Borofsky’s Prisoners is a tour de force. It was made in the mid-eighties just as the era of mass incarceration took hold. Back then prisoners had the same issues – poverty, drug addiction, histories of childhood abuse and adulthoods of transgression, bad circumstance and bad choices – there were just fewer of them.

The opening of the film includes atmospheric music and cuts of the more bizarre statements. It jolts. But don’t think Borofsky is setting these men and women up for a fall. Yes, his artistic hand is all over this, but he gives each of the prisoners plenty of time to pierce through our bullshit and take us right to their reality. If it seems weird, it is probably because Borofsky’s subject live weirdness every day. Borofsky let’s them speak. He shows their common institutionalisation but does not pity them.

Hugely compelling.

I recently visited the International Center for Photography (ICP). I was encouraged to see a photo from Abu Ghraib alongside one of Robert Capa’s Normandy landing photos and Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs from a liberated Nazi concentration camp. All were featured in the enjoyable and current A Short History of Photography exhibition, showcasing works acquired during the tenure of outgoing Director Willis “Buzz” Hartshorn.

Just as Capa and Bourke-White’s photographs are iconic of the WWII conflict, the Abu Ghraib digital photos are iconic and the images of America’s War On Iraq.

Both Capa and Bourke-White, in these instances, were photographers in the thick of it, in the moment, to deliver important news of the day to corners of the globe. Of course, the rise of citizen journalism has put pay to the idea that roving career photographers are now the first to a scene of international significance.

Without doubt the Abu Ghraib images – given their historical and cultural significance and dissemination – are rightfully in the ICP collection. That is not the issue; my questions were about the label:

Unidentified Photographer: [Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh, nicknamed Gilligan by U.S. soldiers, made to stand on a box for about an hour and told that he would be electrocuted if he fell, Abu Ghraib prison, Iraq], November 4, 2003. INKJET PRINT. Museum Purchase, 2003 (113.2005)

Museum purchase? Who would be a recipient of payment for the image? I suspected it might be a case of language and not action. Ever interested by provenance and the accession of items into museum collections, I emailed ICP the following questions:

– Is “Museum Purchase” just a standard note you attach to works or did ICP actually hand over money to someone or some body for the image?

– Did ICP print it off the internet?

– When deciding to acquire it into the collection, what decisions were made about the file, the printing, the paper, the ink?

Kindly, Brian Wallis, the Deputy Director/Chief Curator at ICP responded:

The Abu Ghraib photograph now included in the “A Short History of Photography” was originally printed for the ICP exhibition “Inconvenient Evidence: Iraqi Prison Photographs from Abu Ghraib” (Sept. 17-Nov. 28, 2004).

At the time, only about twenty JPEGs were available, either on the Internet or from files supplied by the New Yorker.* We printed all images then available for the exhibition. They were printed on a standard Epson office printer, on standard 8½” x 11″. office paper, and pinned directly to the wall in the exhibition, in part to emphasize the ephemerality and informational nature of the pictures.

They were printed directly from the web with the understanding that these photographs, taken by U.S. government personnel, were in the public domain. We did not pay for them. The credit line in the current exhibition describes them as “museum purchase” in part because there is no other official museum description for how we obtained them; one could say we purchased the supplies used to print them.

So, no money exchanged hands. A relief of sorts. What one would expect.

I suppose ultimately, I have to give ICP some recognition for its 2004 reflex response to the pressing visual culture issue of the day; for presenting a set of images that for all intents and purposes falls outside of the normal acquisition avenues of major institutions.

ICP’s home-brew solution to show the Abu Ghraib, non-rarefied, non-editioned and thoroughly contemporary set of images is against the grain of many other museums chasing gate receipts through edutainment.

Left: Photo of allied forces landing on Normandy beaches, by Robert Capa; right: Photo of torture at Abu Ghraib, by unknown photographer.

– – – – – – – –

*Seymour Hirsch, who wrote Torture at Abu Ghraib (May, 2004) for the New Yorker, also provide the text for ICP’s Inconvenient Evidence exhibition – the catalogue for which you can download as a PDF

– – – – – – – –

All images: Pete Brook and taken without permission.