You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Rehabilitative’ category.

WORK DETAIL

At the back-end of 2011, I paid a visit to Nigel Poor and Doug Dertinger at the Design and Photography Department at Sacramento State University where they both teach. We talked about a history of photography course that Nigel and Doug co-taught at San Quentin Prison as part of the Prison University Project. At the time, there was no other college-level photo-history course other class like this in the United States. I have no reason to believe that that has changed (although I’d happily be proved wrong — get in touch!) We cover curriculum, student engagement, logistics, and the rewards of teaching in a prison environment.

Toward the end of the conversation we move on to discuss an essay by incarcerated student Michael Nelson. It was a comparative analysis between a Misrach photo and a Sugimoto photo. The highly respected TBW Books recently released Assignment No.2 which is a reissue of Michael’s essay. Packaged in a standard folder and printed on lined yellow office paper, Assignment #2 caught the photobook world a little off guard. Reviewers that dared to take it on admitted to being flummoxed a little. And then won over.

Back in 2011, TBW’s interest hadn’t yet been registered and Poor was still in production of the audio of Michael reading the work for public presentation. TBW Books publisher Paul Schiek has talked about the production of Assignment No.2, but Nigel Poor less so. This is the back-story to one of the most unique photo books of recent years — a book that combines fine art and fine design with an earnest recognition of a social justice need.

–

Scroll down for the Q&A.

–

Q & A

PP: How did you come to teach at San Quentin?

Nigel Poor (NP): I was always interested in teaching in a prison, and I just really never had the time to do it. While I was on a sabbatical [in 2011] I got an email from the Prison University Project saying they were looking for someone to teach art appreciation. I thought it would be a perfect time to teach there and form a class around the history of photography. I really wanted to do something with Doug so we got together to write this class.

PP: What do you look at?

NP: The history of contemporary photography — focusing on the 1970’s to the present. The course is 15 weeks like a regular semester. We met once a week for three hours. We started with early photographers — August Sander, Walker Evans and Robert Frank just to put some context and talk about how these photographers are often quoted and we move forward and show people like Sally Mann, Nan Goldin, Nick Nixon, Wendy Ewald.

Doug Dertinger (DD): Nigel tended to teach about the photographs that dealt with people, portraits, and social issues. My photographs tended to be the ones that dealt with land use and then also media. We struck a nice balance.

DD: The first two classes were strictly on aesthetic language, form, how to experience images, how to talk about them. The first assignment asked them to describe a photograph that doesn’t exist, that they wished they had that would describe a significant moment in their life. In that way they would create a little story for us and we would get to know something about them but they’d also have to use all the language about how you talk about a photograph. It was a really wonderful way to get them to think about making themselves part of the story of the photograph. Even if a photograph isn’t about you, you can bring your experience to it. It’s not solipsism; it is a way of entering photography. The exercise allowed them to take emotional chances with photographs.

In later classes, in 2012, Poor printed out famous photographs on card stock and asked her students to annotate directly upon the images. Click the William Eggleston analysed by Marvin B (top) to see a larger version of it. Kevin Tindall analysed Lee Friedlanders’ Canton, Ohio 1980 (middle), and Ruben Ramirez looked at David Hilliard’s tripychs (bottom).

–

PP: Were there any issues with your syllabus? Did you have to adapt it? Omit anything? Compared say to here at Sacramento State?

NP: I always tell my students, wherever we are, that it is an NC-17 rating. I naively thought I could just show the same images in San Quentin [as at Sac State] but when we started going through the process we were told that we couldn’t show any images that had to do with drugs, violence, sex, nudity, and children. Which is about 95% of photography!

At that point, I wasn’t quite sure how that was going to work but Jody Lewen [Director of the Prison University Project] is an incredible advocate and she didn’t want to presume censorship — Jody wanted the burden of explaation as to why we couldn’t show a particular image to be on the officials of the California Department of Corrections. She set up a meeting with the with Scott Kernan, the [then] Under-Secretary of the California Department of Corrections, and the [then] warden of San Quentin Prison, Michael Martell.

Kernan and Martell wanted me to show all the images that I was using for the class. I basically give them a mini-course in photography from 1970 to the present. We talked for close to two hours. I ended up getting permission to show everything except for four images.

PP: Not the worst case of censorship then?

NP: No. It was kind of a triumph. And, it must be said, without their help — especially Scott Kernan — I don’t think we would have gotten the class in.

PP: Can you describe the philosophy for the course?

NP: The central idea is to expose students to photography but really ask them to think about it quickly in an accessible and emotional way. Nor Doug or I teach from a theoretical or academic point of view. We argue that the images exist and they come to life because of the conversations we have around them. Students learn basic things about framing, form, content, but I really want them to explore all the areas of the photograph.

At the beginning, I describe the photograph as something akin to a crime scene; we are detectives trying to piece all the visual clues together to uncover subtext — perhaps, even secrets of the images that maybe the photographer isn’t even aware of.

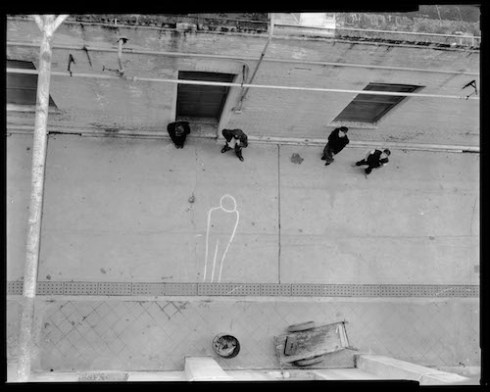

In 2012, Poor was shown an archive of 4×5 negatives of photographs made by the prison administration in the 70s and 80s. The amount of information attached to the images is minimal. Poor broke the archive into 12 loose categories. One from the ‘Violence & Investigations’ category (top) and one from the ‘Ineffable’ category (bottom).

–

PP: Let’s come back to that. Because I want to bring Doug in here. Doug, what did you think when Nigel asked you to co-teach this program inside San Quentin Prison?

DD: I thought great. My parents are doctors and spent the last five years of their careers teaching at Federal Prison System. I taught in prison back in 1993 — one summer just general education stuff. So, when Nigel said that she was going to do this, well, I knew I wanted to partner with Nigel and thought it would be fun, in a way, to see what the what’s going on inside San Quentin.

PP: How do these students fair compared to your students in *free* society?

NP: They really understand the power of education and the importance of being present. I never had a student fall asleep at San Quentin or look at me with that blank expression! They were so hungry, open to conversation. It makes you worry about finding that same intensity outside of the prison setting.

DD: The men they already knew what they were about in a sense and so they came to the class with questions about photography and they understood that photography could reveal the world to them in ways that they were hungry for. A lot of students that I’ve had outside are still trying to figure out what they’re about and they haven’t yet come to their own necessity.

And, some of the men [in San Quentin] somehow understood that learning to talk about images, learning to see the world in a more complex way, could actually change them. I wish there was a way that didn’t sound trite to explain it but I could see transformations in them from the conversations that we had. Every Sunday when I left teaching there I would drive home in silence just contemplating the conversations that we had and how I felt I was becoming a better person for spending time with them. I would like to humbly think that they were too. It was a real back and forth.

Was it Wordsworth that said the imagination is the untraveled traveler? It seemed like when we went to class we all went on these journeys that were very significant for all of us. They were ready to travel.

In Nigel’s final class, she asked her students to annotate on print outs of photos from the newly discovered prison archive, in a manner similar to that they had with famous photographs from the art historical canon. Above are two examples.

–

PP: Earlier you mentioned Sally Mann. I presume a photographer that the authorities think is controversial, a photographer that wider society considers controversial and divides opinion. How did the discussion about Sally Mann’s work pan out?

NP: Some of them definitely had questions about the intent: Why would the mother want to photograph her three children romping around naked on their beautiful farm? But what I wanted to talk about how those images are highly staged and stylized. They’re not documentary images of how her children grew up. They are images about maybe desire about childhood, maybe the photographer inserting herself very clearly into these images. What is Sally Mann saying about the complexities of childhood or how children do have sexual feelings and act out in various ways? The images are about creating a tableau in a sense. It isn’t just about this mother who may have made images that made her children uncomfortable; it’s about creating stages to talk about emotional states of being.

PP: Well, I would think that many of the students are interested in notions of fact, truth, whether you can trust an image. Apart from the body, ones word is pretty much all you have when you’re incarcerated.

NP: We had a discussion very early on about the image always being a fabrication. It’s one person’s opinion putting a frame around the world and we always have to keep that in mind whether it’s documentary work or artist’s work. A lot of them got upset about that because I think they wanted to trust that something was reliable and truthful.

NP: And that may reflect a little bit on what happens to them, as people give evidence, or they want to assert their innocence, or not necessarily their innocence but how something unfolded in their life — this idea that everything is flexible and fluid was a little bit unnerving at times. They couldn’t look at the picture and think that’s exactly what the photographer meant and a few of them got prickly about it. It would come up off-and-on, you know. Can we use the word truth in reality when we’re talking about images and then by extension can you use those words when you’re talking about your own experience?

DD: That was a continuing topic throughout the whole semester. It was interesting too that they I don’t know how to describe it but they knew when they looked at a picture that there were all these elements in there. They explained it to us once: They get one picture from home once every 6 months, they pour over every detail of it and the desire is to create a narrative that they can fully believe and fully immerse themselves in. It was hard for them to understand that at first, at least, that there could be five different opinions about what a photograph was and each one kind of had equal weight.

Detail of Assignment No.2. Courtesy TBW Books.

NP: We don’t have a truth to give [the prisoners]. We’re going to give them our experience and talk about how we see the pictures but we’re going to learn something from them by the way they interpret images. I would see a photograph in a different light, often, after I heard what they had to say about it. I was the teacher in the classroom but it was very much about the power of group conversation. You have to outline what you want to discuss but you never quite know where the conversation’s going to go and I think that gave them a sense of power.

DD: I wonder if it was us not being, in a sense, “guards of meaning” that allowed them to say, ‘Oh, Nigel and Doug can be trusted to be privy to what we think, and they’re going to let us say things, and they’re going to correct themselves in relation to what we’re saying. We can participate, we have equal voice.’

PP: What do your students have to contribute to society?

NP: Before you have an experience in prison as a teacher or someone who’s going in as a civilian volunteer, prisoners are a group of invisible people. Even though I think I’m a thoughtful person, I had assumptions from what I read in the paper, in movies, in news.

PP: What you saw in photographs?

NP: Yeah! That these are going to be scary men, that if you turn your back are going to hurt you, that they’re animals they need to be separated from us and that they’re one-dimensional.

PP: Not so?

NP: When you go in there and you start talking and you see that these are complex, fascinating, thoughtful people; they’re citizens. They are part of our society. Yes, some of them have done terrible things but we have to think about reform and education, and the huge issues of, yes, redemption and forgiveness. How do we deal with those things? I think the only way you can thoughtfully talk about rehabilitation and forgiveness and make change is if you have a personal experience in there — you’re going to change your mind.

Details of Assignment No.2. Courtesy TBW Books.

NP: We need to find ways to use what’s in there to contribute to our society — to tap their experiences and thoughts. I became a better person by going in there and spending time. I learnt what it means to be human.

PP: That is similar to the feedback that I’ve got from other educators who’ve worked in prisons. Do you feel you are a conduit to the outside world. Do you have an added responsibility to share these stories, to share these men and their experiences with the wider public?

NP: I’m a pretty shy person and sometimes it’s difficult for me to talk at parties or whatever. But, now, I call myself the San Quentin bore. All I want to do is talk to people about this amazing experience, what these men are like. I feel very strongly about it, it’s not about me; it’s about this world that’s veiled and it’s about these men that are made invisible.

PP: You are not only a teacher, you are now an advocate. I hear you’re about to give a student the opportunity to “present” his work to the public?

NP: One of the assignments we had for the students was to give them two images from by two different artists and to ask them to analyse them. The only things the student knew about the works were the artists’ names, the dates, and the titles.

One student, Michael Nelson was given an image from Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theater series and a Richard Misrach image of a drive-in theatre from his Desert Canto series.

Richard Misrach. Drive-In Theatre, Las Vegas (1987), from the series American History Lessons.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. La Paloma, Encinitas (1993), from the series Theaters.

NP: While Michael was doing the assignment he was put in the hole, isolation, segregation for four weeks. He wrote an amazing paper talking about those two images. So beautiful that I wanted to get it to Richard Misrach which I was able to do and Richard was blown away by the piece.

Richard had been invited to be part of an event in San Francisco called Pop-Up Magazine which invites 20 to 30 different artists, once a year, to tell six minute stories. Richard’s idea was to read the paper that Michael wrote which was incredible. BUT! Then we started talking about it more, the organizer of Pop-Up decided he wanted Michael to read the paper. So, I went into San Quentin and recorded him reading his beautiful paper.

PP: Fantastic.

NP: It will be edited together. Richard will introduce it, show the two photographs and then play the recording of the student reading. It’s thrilling that this man who’s been in prison for more than half of his life is going to have the chance to be heard by 2,500 people.

PP: Nigel, Doug, Thanks so much.

PP: Nigel, Doug, Thanks so much.

NP/DD: Thank you.

ASSIGNMENT NO.2 (2014)

In an edition run of 1000, Assignment No. 2 will give many more people the opportunity to experience Michael’s words.

By Michael Nelson, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Richard Misrach.

12 x 9.5″ closed / 12 x 30″ open.

20 pages.

2 full color plates.

All proceeds go to the Prison University Project.

Buy here.

–

I was interviewed by ACLU recently: Prisons Are Man-Made … They Can Be Unmade.

The Q&A focuses around the exhibition Prison Obscura and you’ll notice a return to many of my favourite talking points. Still, the work never ends, and I know that ACLU will push out — to an expanded audience — my argument that we should all be more active and conscientious consumers of prison imagery. My thanks to Matthew Harwood for the questions.

AS220 Youth

There are very few organizations like AS220 Youth.

Sure, there’s lots of teen-focused arts organizations across the country but few have achieved the long-lasting and diverse roster of programming and results that AS220 boasts. AS220, similarly to many orgs use arts to connect and empower youth. Very few organizations, however, go into juvenile prisons to deliver photography education. AS220 does.

Very few organisations go into juvenile lock-ups to begin programming in order that they may continue it upon release of the teen with whom they work . AS220 does.

Such continuum is practical AND hopeful. It says ‘We are with you, wherever you are. We share your goal to live free once more.’

AS220 Youth, based in Providence, Rhode Island, gave me the warmest welcome a few years ago. They opened the door so that I could do a workshop with their incarcerated students. I gave a public lecture on my developing ideas about prison imagery. I interviewed the staff and helped students with portfolio reviews. My eyes were open to what a community can be.

Not only did the people stay in my thoughts, the work did too. In late 2013, I included light-paintings made by youth incarcerated at the Rhode Island Training School in Seen But Not Heard (Belgrade, Serbia) a photography exhibition about U.S. juvenile detention. If AS220 Youth did not exist we wouldn’t see these views of the world created by kids who are locked up.

I’ve written about AS220’s youth programs before. I have noted how rare it is that photo programs are inside juvenile detention facilities. AS220 is doing things no-one else can do, or have the imagination to do. You’ve no reason not to help them out.

For the first time in AS220 Youth’s 15-year history, it is conducting a individual giving campaign. They’ve turned to IndieGoGo to push alternative revenue streams having seen public money dry up. AS220 Youth has about half the staff this time last year, and yet it is serving more students than this time last year.

“Since I have been working at AS220 Youth,” says Youth Photography Coordinator, Scott Lapham, “five of my students have been accepted and have gone to or are going to RISD, one to Hampshire, one to the School of Visual Arts, one to Savannah College of Art and Design and one to Mass Art. All of these students are from poor/poverty backgrounds and all but one are students of color. While I couldn’t be prouder of those stats an equally ambitious and important accomplishment is working with students from what we have termed Post Risk backgrounds to achieve emotional and economic stability as adults.”

Bravo to Lapham, his colleagues and the AS220 students.

MONEY, MOVIES, PHOTOS

Help them continue their valuable work: visit the AS220 Youth Futureworlds IndieGoGo page.

Check out more about AS220 Youth program Photo Mem. See the students’ portfolios.

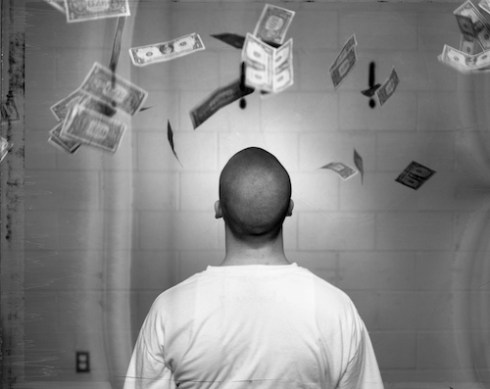

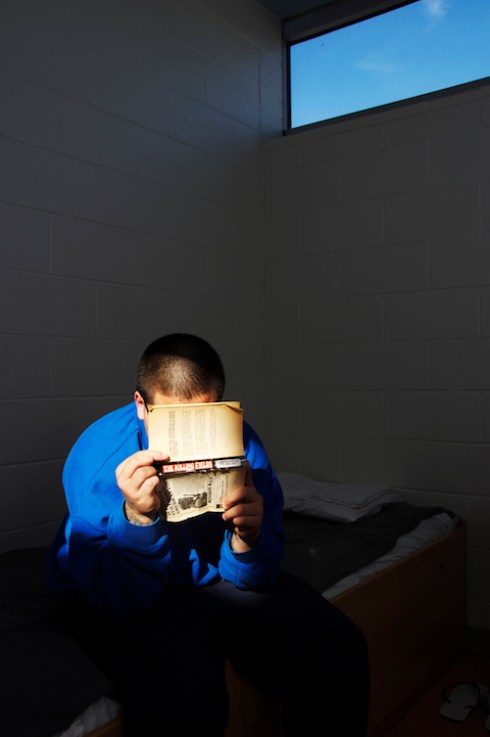

Above is a video about a public art project AS220 Youth made. Throughout this post are images made by youth incarcerated at the Rhode Island Training School.

Image source: Insouciant Writing

THE WRITING ON THE WALL

If you’re in NYC between now and May 22nd go see The Writing on the Wall, an installation by Hank Willis Thomas and Baz Dreisinger. It opened yesterday at the President’s Gallery at John Jay College.

The Writing on the Wall debuted in September 2014, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit (MoCAD) where it was part of the Peoples’ Biennial.

There’s an opening reception tomorrow night, Weds, April 22nd, from 5:30 to 7:30pm.

THE BLURB

The installation is made from essays, poems, letters, stories, diagrams and notes written by individuals in prison around the world, from America and Australia to Brazil, Norway and Uganda. The hand-written and typed pieces were accrued by Dr. Dreisinger during her years teaching in US and international prisons, in the context of both the Prison-to-College Pipeline program she founded at John Jay and her forthcoming book Incarceration Nations: Journeying to Justice in Prisons Around the World.

On a basic and literal level, The Writing on the Wall is about giving voice to the voiceless and humanizing a deeply de-humanized population. It represents a kind of modern-day hieroglyphics, projecting a hidden world into a very public space and allowing a people too often spoken of and for—by politicians and a punishment-hungry public—to speak for themselves, in the most intimate of ways. It is a tribute to the power of the pen, a deliberate verbal intrusion and an assertion that some words need very much to be seen in order to be heard. Indeed the writing is not just on the wall but on the floor, on every inch of the installation space, such that the viewer, unable to look away, is compelled to confront a crisis: global mass incarceration. The piece thus fittingly references the Biblical story in which the writing on the wall, as interpreted by the prophet Daniel, foreshadowed imminent doom and destruction.

Just as mass incarceration is a living, growing global phenomenon, The Writing on the Wall is an ever-evolving installation. With every iteration, it grows and assumes a new shape, because the documents comprising it—material written by those living behind bars—continue to land in Dr. Dreisinger’s hands and mailbox.

THE BIOGRAPHIES

Hank Willis Thomas is a photo conceptual artist working with themes related to identity, history, and popular culture. He received his BFA from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and his MFA in photography, along with an MA in visual criticism, from California College of the Arts (CCA) in San Francisco. Thomas has acted as a visiting professor at CCA and in the MFA programs at Maryland Institute College of Art and ICP/Bard and has lectured at Yale University, Princeton University, the Birmingham Museum of Art, and the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. His work has been featured in several publications including 25 under 25: Up-and-Coming American Photographers (CDS, 2003) and 30 Americans (RFC, 2008), as well as his monograph Pitch Blackness (Aperture, 2008). He received a new media fellowship through the Tribeca Film Institute and was an artist in residence at John Hopkins University as well as a 2011 fellow at the W.E.B. DuBois Institute at Harvard University. He has exhibited in galleries and museums throughout the U.S. and abroad. Thomas’s work is in numerous public collections including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Guggenheim Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art. His collaborative projects have been featured at the Sundance Film Festival and installed publicly at the Oakland International Airport, the Oakland Museum of California, and the University of California, San Francisco. He is an Ellen Stone Belic Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media, Columbia College Chicago Spring 2012 Fellow.

Baz Dreisinger is an Associate Professor in the English Department at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. She is the founder and Academic Director of the college’s Prison-to-College Pipeline Program (P2CP), which offers credit-bearing college courses and reentry planning to incarcerated men at Otisville Correctional Facility. She is also a reporter on popular culture, the Caribbean, world music, and race-related issues for the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and Wall Street Journal, among other outlets; she produces on-air segments for NPR and is the co-producer and co-writer of the documentaries Black & Blue: Legends of the Hip-Hop Cop, which investigates the New York Police Department’s monitoring of the hip-hop industry, and Rhyme & Punishment, about hip-hop and the prison industrial complex. The author of Near Black: White to Black Passing in American Culture (2008) and the forthcoming Incarceration Nations: A Journey to Justice in Prisons Around the World (2015), Dreisinger earned her Ph.D. from Columbia University and has been a Whiting Fellow and a postdoctoral fellow in African-American studies at UCLA.

THE DETAILS

President’s Gallery, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY 899 10th Avenue, Haaren Hall, 6th Floor , NY 10019.

Hours: 9am-5pm, Mon-Fri.

Contact: gallery@jjay.cuny.edu or 212.237.1439.

American photographer Willow Paule has spent half her time, in recent years, in Indonesia. She recounts in PsychoCulturalCinema how she slowly learnt about the past incarcerations of her two friends. Their conversations together led to more questions. Paule writes:

Through my research and conversations with these former prisoners in Indonesia, I discovered that they had faced rampant corruption, extortion, and violence in prison. I found that people were often convicted without solid evidence, that they sometimes possessed only small amounts of narcotics or marijuana but were given long drug distribution sentences, while large time dealers got off with lighter sentences. The person with the fattest wallet got the best treatment.

I learned that mentally ill people often became police targets, and periodically drugs were planted on them in order for police to meet arrest quotas. Once they were locked up, they didn’t necessarily receive adequate care, and they sometimes created turmoil in the cramped cells they shared with the general population. Many people told me disheartening stories about human rights abuses in Indonesian prisons.

My focus is the U.S. prison system, but as I say, dryly and reductively, on my bio page, “problems exist in other countries too.” Paule knows this all too well. She recorded the art that her two friends created as a matter of survival and also their difficult reentry into society. There, as here, jobs are difficult to come by for former prisoners and the stigma of prison lingers long.

The extent to my knowledge on the Indonesian prison system spans the length of Paule’s article. The system sounds dire.

“Prison sentence lengths were decided depending on bribe amounts and prisoners had to pay for a cell or face daily beatings and electrocution in solitary confinement,” writes Paule.

Connecting Paule’s years-old inquiry to today, in the U.S., is Paule’s desire to repeat the methodology and record the stories of returning citizens in America.

There’s no shortage of people in this country with whom Paule could meaningfully connect and weave their history and story over a long period as she did in Indonesia. It takes more than just images though; I encourage Paule and all young photographers to use audio, family archives, collaborative processes and — as Paule did here — a focus on non-photo 2D artworks. Most of all, I encourage young photographers to empower not only individuals impacted by incarceration through the telling of their stories but also to empower small local communities by exhibiting and programming the work with those most closely implicated in the issue.

Simply put, a show at the local community centre is as important as one in the brand name gallery downtown. The former deals in hearts and minds, the latter in sales.

TEACHING PHOTOGRAPHY INSIDE

I’ve known about Vance Jacobs work in a Medellin Prison for as long as it has been in published form, but this recent post by StoryBench reminded me of the excellent and brief video reflection Jacobs gives about his time teaching prisoners to use cameras to document their own lives. Originally, Jacobs was going to be the only person photographing, but at the eleventh hour the sponsoring NGO for thre project changed the concept and he was asked to educate a dozen men in prison.

“You could tell it had been a long time since the prisoners in my class had received this much attention. But I also had high expectations and those expectations led to it being a very important experience. They started taking a tremendous amount of pride in their work and they started to understand that criticism could be a really important part of their work and theta they could grow from it,” says Jacobs.

This type of introspection and self-documentation is vital, in my opinion.

At the final exhibit inside the prison of 35 images, 5 went missing. “To have a photo stolen was a badge of honor,” says Jacobs. “It meant someone thought they were worth stealing.”

BIO

Vance Jacobs, a San Francisco-based photojournalist and filmmaker whose work has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic Books and Esquire magazine. He talks about his creative process and behind the scenes details of his different shoots at his ‘Behind the Lens’ YouTube channel. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

See features on Jacobs’ work at GOOD, WonderfulMachine, Photographer on Photography and PDN Online.

The Big Graph (2014). Photo: Courtesy Eastern State Penitentiary.

Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site Guidelines for Art Proposals, 2016

Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia has announced some big grants for artists working to illuminate issues surrounding American mass incarceration.

READ! FULL INFO HERE

ESP is offering grants of $7,500 for a “Standard Project” and a grant of $15,000 for specialized “Prisons in the Age of Mass Incarceration Project.” In each case the chosen installations shall be in situ for one full tour season — typically May 1 – November 30 (2016).

DEADLINE: JUNE 17TH

THE NEED

ESP has, in my opinion, the best programming of any historic prison site when it comes to addressing current prison issues. Last year, they installed The Big Graph (above) so that the monumental incarceration rates could tower over visitors. Now, ESP wants to explore the emotional aspects of those same huge figures.

“Prisons in the Age of Mass Incarceration will serve as a counterpoint to The Big Graph,” says ESP. “Where The Big Graph addresses statistics and changing priorities over time, Prison in the Age will encourage reflection on the impact of recent changes to the American criminal justice system, and create a place for visitors to reflect on their personal experiences and share their thoughts with others.”

ESP says that art has “brought perspectives and approaches that would not have been possible in traditional historic site programming.” Hence, these big grant announcements And hence these big questions.

“Who goes to prison? Who gets away with it? Why? Have you gotten away with something illegal? How might your appearance, background, family connections or social status have affected your interaction with the criminal justice system? What are prisons for? Do prisons “work?” What would a successful criminal justice system look like? What are the biggest challenges facing the U.S criminal justice system today? How can visitors affect change in their communities? How can they influence evolving criminal justice policies?” asks ESP.

While no proposal must address any one or all of these questions specifically they delineate the political territory in which ESP is interested.

“If our definition of this program seems broad, it’s because we’re open to approaches that we haven’t yet imagined,” says ESP. “We want our visitors to be challenged with provocative questions, and we’re prepared to face some provocative questions ourselves. In short, we seek memorable, thought-provoking additions to our public programming, combined with true excellence in artistic practice.”

“We seek installations that will make connections between the complex history of this building and today’s criminal justice system and corrections policies,” continues ESP. “We want to humanize these difficult subjects with personal stories and distinct points of view. We want to hear new voices—voices that might emphasize the political, or humorous, or bluntly personal.”

GO TO AN ORIENTATION

ESP won’t automatically exclude you, but you seriously hamper your chances if you don’t attend one of the artist orientation tours.

They occur on March 15, April 8, April 10, April 12, May 1, May 9, May 15, June 6.

Also, be keen to read very carefully the huge document detailing the grants. It explains very well what ESP is looking for including eligibility, installation specifics, conditions on site, maintenance, breakdown of funding (ESP instructs you to take a livable artist fee!), and the language and tone of your proposal.

For example, how much more clear could ESP be?!

• Avoid interpretation of your work, and simply tell us what you plan to install.

• Avoid proposing materials that will not hold up in Eastern State’s environment. Work on paper or canvas, for example, generally cannot survive the harsh environment of Eastern State.

• Be careful not to romanticize the prison’s history, make unsupported assumptions about the lives of inmates or guards, or suggest sweeping generalizations. The prison’s history is complicated and broad. Simple statements often reduce its meaning.

• A proposal to work with prisoners or victims of violent crime by an artist who has never done so before, on the other hand, will raise likely concern.

• Do not suggest Eastern State solely as an architectural backdrop. Artist installations must deepen the experience of visitors who are touring this National Historic Landmark, addressing some aspect of the building’s significance.

• Many successful proposals, including Nick Cassway’s Portraits of Inmates in the Death Row Population Sentenced as Juveniles and Ilan Sandler’s Arrest, did not focus on Eastern State’s history at all. They did, however, address subjects central to the topic we hope our visitors will be contemplating during their visit.

• If you are going to include information about Eastern State’s history, please make sure you are accurate. Artists should be sensitive to the history of the space and only include historical information in the proposal if it is relevant to the work. Our staff is available to consult on historical accuracy.

• Overt political content can be good.

• The historic site staff has been focusing explicitly on the modern American phenomenon of mass incarceration, on questions of justice and effectiveness within the American prison system today, and on the effects of race and poverty on prison population demographics. We welcome proposals that can help engage our visitors with these complex subjects.

• When possible, the committee likes to see multiple viewpoints expressed among the artists who exhibit their work at Eastern State. Every year the committee reviews dozens of proposals for work that will express empathy for the men and women who served time at Eastern State. The committee has accepted many of these proposals, generally resulting in successful installations. These include Michael Grothusen’s midway of another day, Dayton Castleman’s The End of the Tunnel, and Judith Taylor’s My Glass House. The committee rarely sees proposals, however, that explore the impact of violence on families and society in general, or the perspective of victims of crime. Exceptions have been Ilan Sandler’s Arrest (2000 to 2003) and Sharyn O’Mara’s Victim Impact Statement (2010). We hope to see more installations on those themes in the future.

PAST GRANTEES

Check out the previous successful proposals and call ESP! Its staff are available to discuss the logistics of the proposal process and the history and significance of Eastern State Penitentiary.

DEADLINE: JUNE 17TH, 2015

Additional Resources

Sample Proposals

Past Installations

For more information contact Sean Kelley, Senior Vice President and Director of Public Programming, at sk@easternstate.org or telephone on (215) 236-5111, with extension #13.

Prison Obscura is currently at the mid-point of its New York showing at Parsons The New School of Design. At this moment, I wanted to share with you a few installation shots made by Marc Tatti for Parsons.

I also took the opportunity to re-issue the Prison Obscura catalogue essay (originally published by Haverford College) on Medium. Read Can Photographs of Prisons Improve the Lives of Prisoners?

I have hi-res images of all artworks and installation shots. Should you need any, drop me a line.

Enjoy the weekend!

All images: Marc Tatti.