You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Visual Feeds’ category.

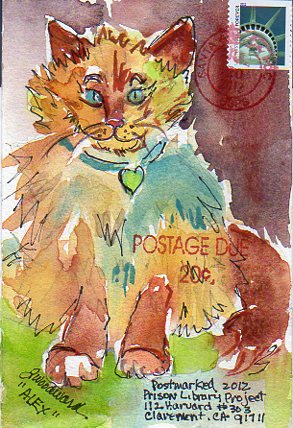

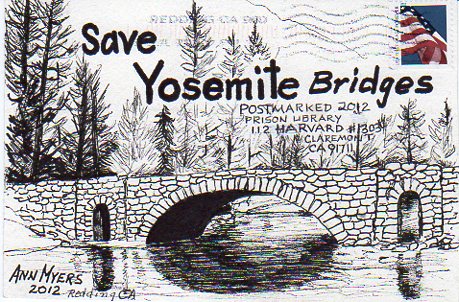

The Prison Library Project will be having a mail art exhibition in October 2012 and invites inmates, families and those who look to improve the lives of those incarcerated to participate:

The Prison Library Project receives hundreds of letters every week from inmates across the country. These letters requesting books and dictionaries, are often beautifully illustrated. In the spirit of these talented prison artists the Postmarked show was created, using the envelope as a canvas to create and share mail art.

The art of letter writing and the use of “snail mail” is on the decline, a casualty of the electronic age. But who among us does not smile when we received a letter in our mailbox? Who doesn’t thrill to find art instead of junk mail and bills? The Postmarked show is a chance for all of us to reconnect with the magic of “snail mail” while helping a population whose voice, if heard at all, is limited to the humble envelope, letter and pen.

Interested participants may decorate, illustrate or create art on an envelope and mail it in for the Postmarked mail art exhibition and fundraiser. Send submissions to:

Postmarked 2012

Prison Library Project

112 Harvard #303

Claremont CA 91711

Entries must be postmarked by September 30, 2012.

Only the side with the official USPS Postmark/barcode will be displayed. Mail art may be painted, stamped, collaged, printed, decorated or constructed. It may be any shape and size that will go through the mail and receive an official postmark.

“Mail may get worn or torn through the mail, but the handling process is an important part of the theme,” says organiser, Rachel McDonnell

Mail will be opened only by the person who purchases the art envelope.

Exhibition: October 5 – November 2 at the Claremont Forum Bookshop & Gallery. Opening Reception: Friday, October 5 Final Bid Party: Friday, November 2, 6:30 – 8:00pm

For more information, see PLP’s Postmarked blog or contact Rachel McDonnell at rachel@claremontforum.org

The Prison Library Project is a prison book and literacy program which sends thousands of books, study aids, educational and spiritual resources to inmates nationwide.

Artist’s impression of projected cellphone imagery.

ART

Stop, a video installation will put faces to the numbers – hundreds of thousands – of people who are unjustly detained by police.

Stop is proposed by New York based Dread Scott and by Joann Kushner, an artist working in Liverpool, UK. As described by Dread Scott:

“Stop will be a projection of portraits of several youth from East New York, Brooklyn and Liverpool, UK. Brooklyn will be on one wall and Liverpool will face them on the other. The life-sized projections will stand and face each other, the audience will be in the middle. Over time, each of the young adults will reveal how many times they have each been stopped by the police during their lifetime. The youth will be having a virtual “conversation” across an ocean with each other as well as with the audience.”

PHOTO

Yesterday, I posted a long conversation with Nina Berman about Stop & Frisk. Berman had not found any other fellow photographers working on the issue of Stop & Frisk. I found one other photographer (who’s work is ongoing and wishes not to publicize it yet) and one artist – Dread Scott.

Dread’s a lovely guy; I’ve written about his work on the prison industrial complex before and I interviewed him last year during PPOTR. Here’s what he says about this Stop & Frisk and this project:

“Last year, New York police stopped almost 700,000 people as part of their “Stop and Frisk” policy. The overwhelming majority, about 90%, were doing nothing wrong at the time and were completely innocent. Most were young and Black or Latino. A similar policy exists in Liverpool and developed after NY police chief William Bratton was invited to be a consultant in another UK city, Hartlepool, in 1996.”

It should be added that UK Prime Minister David Cameron wanted to appoint Bratton as Commissioner of London’s Metropolitan Police Service following the London Riots of August 2011. Cameron was later overruled by Home Secretary Theresa May, who insisted that only a British citizen should be able to run the Service.

Dread has led photography and art workshops with young adults from East NY Brooklyn (a neighborhood with one of the city’s highest police Stop and Frisk rates) and Joann has been working with similar youth in Liverpool. Using cell phones, students have made a powerful series of photographs about their neighborhoods and lives.

Stop will be exhibited in Rush Arts Gallery, NYC from September 13th, 2012.

START KICKING

Kickstarter has definitely reached its saturation point; The Onion’s take made me laugh hardest.

But you don’t even need to feel guilty about this one; Dread’s already reached his target (sure, he’d like a little extra: who doesn’t?)

What’s more important is the message of his work. Until now, I’ve never seen connections made between the US and the UK – between New York and Liverpool – over the Stop & Frisk issue. The issue is rarely framed within the context of youth; we don’t think of the victims as kids … but in many cases they are.

Stop & Frisk is a canary issue. How the controversy resolves itself will be an indication of whether we have progressed; if we are interested and involved in the welfare of others, or if we remain indifferent. It’s driven by Homeland Security dollars and it messes with peoples’ lives. It’s born out of a divided society, just as prisons were. Now the heavy-handed response is on peoples’ doorsteps.

David Adler has been collecting prisoner made portraiture since 2006.

Adler’s work is very similar to Alyse Emdur‘s Prison Landscapes (readers will know Emdur is a favourite of mine.) But in fact, Adler and Emdur approach the visual culture and the act of collecting the photos very differently. I’ll be publishing an interview with Adler shortly, but to summarise, Emdur is thinking about social justice whereas Adler is thinking about the economics of the system. Both consider the painted backdrops as significant contributions to American artistic production.

Adler thinks of his work as a theoretically infinite, open-source project, that anyone could take on. Conversely, Emdur considers her presentations as collaboration with each of her subjects.

More to come.

Meanwhile, if you’re in NYC, Adler’s exhibition Prisoner Fantasies: Photos from the Inside is showing at the Clocktower Gallery in Lower Manhattan, until the end of August. Also, you can read a brief interview with Adler, by Harry Cheadle for VICE.

[Yes, the visual similarity between this post and the last was intentional.]

I Heart Gordon Stettinius’ humour. Especially in light of the horrendous Olympian portraits, this work seems like a good time to reflect on why and how we make (bad) portraits.

PRISON MAP

Prison Map is the most complete visualisation project of America’s prison system that I’ve come across. No surprise that it takes the form of satellite imagery and no surprise it was made with the aid of computer code.

Prison Map is the work of Josh Begley, an Interactive Telecommunications graduate student at NYU. He developed the project as part of Jer Thorp‘s Data Representation class.

The title is a little misleading. “It’s not a map,” says Begley, “It’s a snapshot of the earth’s surface, taken at various points throughout the United States. It begins from the premise that mapping the contours of the carceral state is important.”

A premise I can agree with. In my meagre attempts to comprehend the size and impact of contemporary prison construction, I’ve compared state-commissioned aerial photography with the fine art photography of David Maisel. I’ve also admired the Incarceration Nation project by non-profit Thousand Kites using roving Google Earth imagery to describe penal architectures (although the manual labour behind Incarceration Nation always seemed to big and ultimately wasteful; an irony not lost for a project commenting on the wasteful prison industrial complex.)

Begley had made cursory use of the CDCr’s own aerial photographs for his earlier Prison Count, but that project is shallow by comparison to Prison Map.

SIGNIFICANCE

Prison Map both orders and exposes the sprawl of prisons in our society; Begley was motivated by the frustration that words and figures often fall short. Again, it is a premise I’m very sympathetic to. What difference does it make if the figure you use to describe an invisible problem has an extra zero or not?

“When discussing the idea of mass incarceration, we often trot out numbers and dates and charts to explain the growth of imprisonment as both a historical phenomenon and a present-day reality,” says Begley. “But what does the geography of incarceration in the US actually look like? What does it mean to have 5,000 or 6,000 people locked up in the same place? What do these carceral spaces look like? How do they transform (or get transformed by) the landscape around them?”

TOOLS

Begley used the Correctional Facility Locator, a project of the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI)*, as his primary tool. The Correctional Facility Locator database includes the hard-to-locate latitude and longitude coordinates of every carceral facility counted in the 2010 US census.

Begley notes that the Correctional Facility Locator is the first and only database to include state and federal prisons alongside local jails, detention centers, and privately-run facilities. 4,916 facilities in total. It is the only such database of which I’m aware.

Using the Google Maps API and the Static Maps service, Begley and Thorp wrote a simple processing sketch that grabbed image tiles at specified latitudes and longitudes, saving each as a JPEG file. The processing sketch cycled through 4,916 facilities.

Some of the captured images were more confusing than instructive – and dealing with nearly five thousand images proved unwieldy – so Begley selected “only” 700 (14%) of the best photos. If you want to see Begley’s entire data set, you can do so here.

USES

The question that this project raises is what can be done with this visualised data to effect change and propel social justice? Artist Paul Rucker used maps created by Rose Heyer (also of PPI) to compose Proliferation. Begley has culled the images; what digital collaging, comparative analysis and collaborations can be constructed with the images?

Perhaps information is more important than images? Toward the end of his TEDxVancouver Talk, Jer Thorp (Begley’s NYU professor) talks about how data represents real life events and their associated emotions. Movements mapped to, fro and between prisons may begin to describe the mass movement within mass incarceration. Specifically dealing with New York State, the Spatial Information Design Lab at Columbia University investigated these types of visualisation with its Million Dollar Blocks project.

An App about the forced migrations within the prison industrial complex is waiting to be built. The first stumbling block is access to data. The prison system is not renowned for being open with its information.

– – – – – – – –

If you’d like to know more, Josh Begley can be contacted at josh.begley[at]nyu.edu

– – – – – – – –

Thanks to Sameer Padania for the tip.

– – – – – – – –

*PPI is one of the most imaginative research groups illuminating the dark recesses of our carceral landscape. PPI Director, Peter Wagner, was a PPOTR interviewee last year offering passion and intelligent analysis of the prison industrial complex. I’ve been aware – and made use – of many PPI resources in the past, but until now was unaware of the Correctional Facility Locator. Kudos to PPI.

Last year, in the article Photographing the Prostitutes of Italy’s Backroads: Google Street View vs. Boots on the Ground, I compared the work of artists Mishka Henner and Paolo Patrizi both of whom were making images of prostitution on the back roads of Spain and Italy.

I argued that the photographs by Patrizi, due to their physical and emotional proximity had more relevance. Patrizi actually went to the roadside locations whereas Henner, making use of Google Street View, had not.

Around the same time, Joerg Colberg posted some thoughts about Henner’s No Man’s Land.

Shortly thereafter, Mishka Henner emailed me and mounted an impassioned defense of his work. Henner felt he had been “thrown to the cyber-lions.” Not wanting to see anyone with his or her nose bent, I offered Henner a platform on Prison Photography for right of reply.

CONVERSATION

PB: What was your issue with the commentary on No Man’s Land?

MH: There’s a section of the photo community judging No Man’s Land according to a pretty narrow set of criteria. So narrow they’re avoiding one of the elephants in the room, which is what role is left for the street photographer in the age of Google Street View? Comparing No Man’s Land to other projects on sex workers could be interesting but the way it’s done here is resulting in a pretty narrow discussion about whether it’s valid, ethical or just sensationalistic. I don’t see how that helps move documentary forwards. All the projects you mention, including mine, assert themselves as documents of a social reality. But in your discussion, this is secondary to how they make you feel and Colberg even argues Patrizi’s approach makes you care. My motivation isn’t to make you feel or to care – it’s to make you think.

MH: No Man’s Land uses existing cameras, online interest groups, and one of the subjects interwoven in the history of photography. And I think the ability to combine these elements says something about the cultural and technological age we live in. In some photographic circles, that’s the way it’s being discussed and I’m surprised Colberg and yourself have dismissed it in favour of more reactionary arguments that seem to hark back to what I see as a conservative and nostalgic view of the medium.

PB: Well, if preference for boots on the ground and a suspicion of a GSV project is reactionary, then okay. Why did you use GSV for No Man’s Land? Are you opposed to documentary work?

MH: This is documentary work, how can it not be? And what’s this suspicion of GSV? Would you have been suspicious of Eugene Atget walking the streets with his camera? I’m sure many were at the time but that suspicion seems ridiculous now. And your response is reactionary because it validates and dismisses work according to quite spurious and nebulous criteria. What does it matter if I released the shutter or not? A social reality has been captured by a remote device taking billions of pictures no one else ever looked at or collected in this way before. You’re only seeing this record because I’ve put it together. The project is about the scale of a social issue, not about trying to convince a viewer that they should have pity for individual subjects. Yet in these circles, the latter uncritically dwarfs the former as though it’s the only valid approach.

MH: Paolo Patrizi’s A Disquieting Intimacy is evidently an accomplished visual body of work, as is Txema Salvans’ The Waiting Game but to argue they offer a deeper insight into the plight of sex workers is, I think, generous to say the least.

MH: The assumption underlying much of the critiques of No Man’s Land (in particular Alan Chin’s) is that there’s no research and it’s a lazy, sensationalistic account of something fabricated. But what if I told you it was researched and took months to produce; what basis would there be then for dismissing it? Doesn’t research inform 90% of every documentary photographer’s work (it did mine, maybe I wasn’t doing it right)?

What’s left unsaid in these critiques is that No Man’s Land doesn’t fit a rather narrow and conservative view of what one community believes photography should be. The fact we’re drowning in images and that new visions of photography are coming to light are a scary prospect to that community, hence the reactionary and defensive responses. But there’s more to these responses than simply validating boots on the ground. You’re prioritising a particular way of seeing and rejecting another that happens to be absolutely contemporary.

PB: I think we can agree Patrizi is accomplished. I was deliberately lyrical in my description of his work and I meant it when I was personally moved by Patrizi’s work. That is a personal response.

MH: That’s fine, but what does Patrizi tell us that is missing from No Man’s Land? Is the isolation and loneliness of a feral roadside existence and the domestication of liminal spaces really that much more evident in one body of work than the other? Surprisingly – given your sympathy for Patrizi’s’ approach – even the women’s anonymity is matched in each project. No captions, no locations, no names, and no personal stories. Just a well-researched introductory text that refers in general terms to the women’s experiences. I think you’re viewing the work through rose-tinted spectacles.

PB: I can’t argue with your point about anonymity. There may be an element of gravitating toward [Patrizi’s] familiar methods. This might be because reading the images resultant of those methods is safe for the audience; they find it more easily accessible, possibly even instructive in how they should react?

MH: Working in documentary for many years, I can’t deny I aimed for these lofty aspirations. But I now consider the burden of sympathy expected from a narrow language of documentary to be a distracting filter in the expression of much more complex realities. Pity has a long and well-established aesthetic and I just don’t buy it anymore. In themselves the facts are terrible and I don’t need a sublime image to be convinced of that. In the context of representing street prostitution, striving for the sublime seems a far more perverse goal to me than using Street View and much more difficult to defend.

MH: Alan Chin’s comments surprised me because I wouldn’t expect such a knee-jerk reaction from an apparently concerned photographer. But his work is a type of documentary that I’m reacting against; a kind of parachute voyeurism soaked in a language of pity that reduces complex international and domestic scenarios into pornographic scenes of destruction and drama. It’s the very oxygen the dumb hegemonic narrative of terror thrives on and I reject it. Why you would pick his critique of my work is beyond me – we’re ships passing in the night.

PB: I quoted Chin because he and I were already been in discussion with others about the many photo-GSV projects. He represented a particularly strong opposition to all the GSV projects including No Man’s Land.

MH:No Man’s Land is disturbing, I agree. And it troubles and inspires me in equal measure that I can even make a body of work like it today. But it isn’t just about these women, it’s also about the visual technologies at our disposal and how by combining them with certain data sets (in this case, geographic locations logged and shared by men all around the world), an alternative form of documentary can emerge that makes use of all this new material to represent a current situation. It appeals to me because it doesn’t evoke what I think of as the tired devices of pity and the sublime to get its point across.

PB: It’s not that I don’t like No Man’s Land, but I prefer Patrizi’s A Disquieting Intimacy; it is close(r) and it is technically very competent work. There’s plenty of art/documentary photography that doesn’t impress me as much as Patrizi’s does. A clumsy photographer could’ve dealt with the topics of migration and the sex industry poorly. I don’t think Patrizi did.

MH: I don’t know what you mean by clumsy. If by clumsy you mean a photographer who shows us what they see as opposed to what they think others want to see then bring it on, I’d love to see more of that. No Man’s Land might seem cold and distant, it might even appear to be easy (it isn’t), but it’s rooted in an absolutely present condition. What you consider to be its weakness – its inability to get close to the photographic subject, its struggle to evoke pity – is what I consider to be its strength.

PB: The detachment is the problem for all concerned. People may be using your work as a scapegoat. This would be an accusation that I could, partly, aim at myself. Does your work reference the frustration of isolation and deadened imagination in a networked world?

MH: At first, I reacted strongly to your description of my work as anemic but now I think it’s a pretty good description of the work. And it’s an accurate word for describing what I think of as the technological experience today, our dependence on it and its consequences.

PB: Consequences?

MH: I know, like most working photographers, that for all the fantasies of a life spent outdoors, much of a photographer’s workload happens online. And if you’re a freelancer, the industry demands that you’re glued to the web. It’s not the way I’d like it to be; it just happens to be the world I’m living in. And anyone reading this online on your blog is likely to share that reality. So it seems natural and honest that as an artist, I have to explore that reality rather than deny its existence.

PB: For audiences to grasp that you’re dealing – with equal gravity – two very different concerns of photography (the subject and then also contemporary technologies) opens up a space for confusion. Not your problem necessarily, but possibly the root of the backlash among the audience.

MH: Well, it’s surprising to me that few critics have actually discussed the work in relation to the context in which it was produced, i.e. as a photo-book. If even the critics are judging photo-books and photographs by their appearance on their computer screens, then I rest my case.

PB: What difference does the book format make to your expected reactions to the body of work?

MH: For one thing the book takes the work away from the online realm and demands a different reading. That in itself transforms it and turns it into a permanent record. Otherwise I’d just leave the work on-screen. I recently produced a second volume and intend to release a third and then a fourth, continuing for as long as the material exists.

PB: On some levels, people’s reactions to your work seem strange. If people are so affronted, they should want to change society and not your images?

MH: Too often, I find that beautifully crafted images of tragedy and trauma have become the safe comfort zones to which our consciences retreat. It’s something people have come to expect and it doesn’t sit easily with me. When I think of No Man’s Land, I keep returning to Oscar Wilde’s preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray:

No artist has ethical sympathies.

An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style.

All art is at once surface and symbol.

Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril.

Those who read the symbol do so at their peril.

It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.

Diversity of opinion about a work of art shows that the work is new, complex and vital.

When critics disagree the artist is in accord with himself.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

No Man’s Land will be on show – from May 3rd until 27th – at Blue Sky Gallery, 122 NW 8th Avenue, Portland, OR 97209. Tuesday – Sunday, 12-5 pm.

Video still from a surveillance camera in Richmond Heights Jail, St. Louis, Missouri. Anna Brown has just been carried into the cell and laid on the floor. She is dying.

Over on BagNewsNotes, Karen Hull has written a brief but poignant piece about the death of Anna Brown, a young, Black homeless woman. In particular, Hull considers the role surveillance cameras have played in the investigation into Brown’s death.

In September, 2011, Brown died in a jail cell in St. Louis, Missouri. She had visited three hospitals earlier in the evening complaining of pain in her legs but she was turned away by each of them. When she protested and insisted she needed treatment she was arrested and booked into jail. 15 minutes after they closed the door she was found dead. Brown had not used drugs, yet an officer later casually remarked and assumed she had.

Hull:

Race, health care, and surveillance culture come simultaneously into play here. That the healthcare system can be reckoned as something other than a force for good is balanced by the good of a typical “evil”: surveillance. Without surveillance film, it’s possible the death of this young woman would have gone unnoticed. […] as much controversy as there is surrounding CCTV, rest assured that in the future, we will increasingly witness via surveillance.

The footage was attained by the St. Louis Dispatch via a sunshine request.

Full surveillance video of Anna Brown’s demise here. MSNBC provides the backstory.

NOT UNIQUE

Unfortunately, the mistake of authorities to think of a distressed woman as manic instead of in need of urgent medical attention is not unprecedented. In 2009, Cayne Miceli suffering an asthma attack was dragged away from a New Orlean’s hospital and put into a five point restraint in the Orleans Parish Prison. She was disruptive, fearful and loud, but the medical staff at the jail should have known the immediate threat to her life. She died of hypoxic brain injury, cardiac arrest and asthma, brought on by the horizontal position of her restraint.