You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Photographers of Prisons’ tag.

An interior view of the dining facility at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. Wathiq Khuzaie for Getty Images Europe.

Yesterday, my good friend Debra Baida sent me through the link to the New York Times Abu Ghraib – Baghdad Bureau Blog. This came at the same moment I was preparing a post to discuss the first images to come out of the renamed, refurbished and relaunched Baghdad Central Prison.

By far the best, and possibly the only, extended photo essay of Abu Ghraib Baghdad Central Prison is by Wathiq Khuzaie of Getty Images Europe. There is also this brief video from the BBC.

Iraqi security personnel stand guard at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. The Iraqi Ministry of Justice has renovated and reopened the previously named "Abu Ghraib" prison and renamed the site to Baghdad Central Prison. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe

New Era, New Penology

The BBC noted, “Along with the change of name, the Iraqi justice ministry is trying to change both image and reality, billing it as a model prison, open to random inspection by the Red Cross and other humanitarian organisations.”

This transparency is a refreshing change to the policy of Abu Ghraib’s former operators. The work is not yet complete though and the upgrade is ongoing. The BBC describes, “[The prison] will eventually be the city’s main jail, holding about 12,000 inmates. Initially, only one of its four sections will be used. There are already about 300 prisoners there to test it out and, once the prison has been officially inaugurated, that figure will rise to 3,500.”

So, not only do Iraqi authorities want to repurpose the institution, they want to make it the penal institution of “The New Iraq”. This is an ambitious policy riddled with dangers; the site is loaded with memory and controversy. As the New York Times notes, “the promise of a new era can also be a time for remembrance.”

I highly recommend one goes onto read accounts from Iraqis, correspondents and photographers who lived and recorded Abu Ghraib’s recent history, particularly photographer Tyler Hicks’ account of Saddam’s prison amnesty in October 2002 that turned from celebration to human catastrophe.

Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe

An interior view of one of the cells at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe

Two things struck me about the photographic series of the new prison. Firstly, the number of flags, insignia and national colours across walls, above fences and emblazoned on uniforms. The Iraqi authorities have stamped their identity all over this project. It is the presentation necessary to supersede Abu Ghraib’s reputation.

Secondly, the pastel palette of many of the interior shots – namely the ubiquitous lilac. I want to know who has the decision-making power at Baghdad Central Prison! However, I suspect lilac paint was cheap and readily available; so it wasn’t so much a decision – more a fact created by circumstance.

Interior view of the barbers shop at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe.

Following that logic, one could presume lilac and purple fabric & thread is also at a surplus in Baghdad…

Interior view of sewing machines at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe.

I don’t want to sound facetious, I was just shocked by the light purple, which according to colour theory is supposed to evoke emotional memory and nostalgia. Darker purples are supposed to represented, nobility, royalty and stability. From those evocations one is instilled with wisdom, independence, dignity and creativity.

If Baghdad Central Prison is to spur such emotional response in its inmate population it will succeed where many, many prisons have failed.

Basically, I am hopeful that the new prison can operate justly and succeed with the rehabilitation it emphasised this week. And despite all the lilac, soft-furnishings and current open media access – in reality it remains a prison with doors, locks and guards.

Interior view of cell doors at the newly opened Baghdad Central Prison in Abu Ghraib on February 21, 2009 in Baghdad, Iraq. The Iraqi Ministry of Justice has renovated and reopened the previously named "Abu Ghraib" prison and renamed the site to Baghdad Central Prison. According to the Iraqi Ministry of Justice about 400 prisoners were transferred to the prison which can hold up to 3000 inmates. The prison was established in 1970 and it became synonymous with abuse under the U.S. occupation. Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images Europe.

BURN Magazine, under the fiscal umbrella of the Magnum Cultural Foundation, have announced a $10,000 grant “to support [the] continuation of the photographer’s personal project. This body of work may be of either journalistic mission or purely personal artistic imperatives”

I am encouraging people to take on the difficult task of securing prolonged and necessary time with a prison/jail/detention-centre population in order to faithfully describe the stories and systems of its particular circumstance. On top of that your product must be “work is on the highest level”.

It’s a tall order but if you have carried out portrait or documentary photography in a site of incarceration before (I know many of you), then submit an application to continue that critical and valuable work. It will have to better than my attempt.

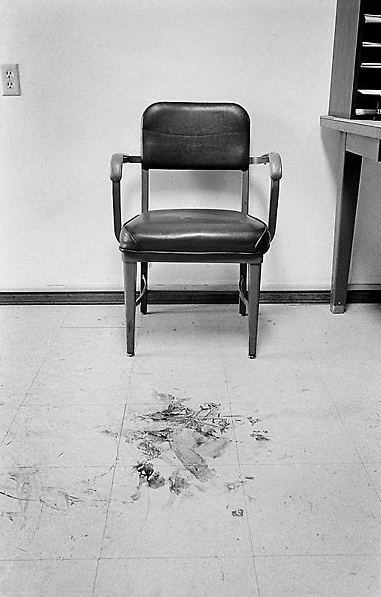

San Pedro Prison, La Paz. July 2008.

Hmm. On the same day I encourage photographers to attempt access into sites designed to be impenetrable, the government and police in my home country have introduced “laws that allow for the arrest – and imprisonment – of anyone who takes pictures of officers ‘likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism’.” (British Journal of Photography via In-Public)

BURN Magazine is a new(ish) venture by David Alan Harvey whose got a Magnum portfolio and his own internets.

At the 2009 World Press Photo Awards, it was the work of Roger Cremers‘ tourist behaviours at Auschwitz-Birkenau that caught my eye.

In a photography climate that frequently pours cynicism and scorn on global tourism, Cremers is on tricky ground. He can thank Martin Parr for making his path a little more tricky. How do we not dismiss Cremers’ work as stating the obvious?

Cremers does not reduce his tourists to unthinking crowds. Instead, he isolates his subjects; they’re in their own thoughts, their own photo-trance and their own space. There is no throng at Auschwitz and nor is there in Cremers’ images … except for the tightly-packed shuttle bus.

Many of the prisons and concentration camps of the Third Reich have since been incorporated into the culture & heritage industry. Auschwitz receives 750,000/year and Dachau 900,000/year (Young, 1993). In the fifteen years since, one would expect figures to have risen.

Lennon & Foley’s excellent book Dark Tourism argues these sites ‘constitute attractions and they cannot simply be classified as “Genocide Monuments” since a monument in this context conveys a different meaning’. Furthermore, ‘these sites present major problems in interpretation … major problems for the language utilized in interpretation to adequately convey the horrors of the camps. Consequently, historical records and visual representation is extensively used.’

Used not only by the site curators, but created by the visitors for later return. I am not comfortable saying that visitors to Auschwitz consume in the same way tourists do at other sites. I believe the subjects of Cremers photographs are creating their own visual memories of the site AND I believe Auschwitz visitors do so with a consciously different sensibility than at other sites.

I visited Auschwitz in 2000. Words were redundant, the scale of the crime overwhelming and agog meditation my modus operandi. It would be cognizant of the average visitor – knowing they may never return to the site – and unable to muster words, to muster a few images.

Recommended: the Guardian Photo Editor’s summary of the World Press Photo Awards, 2009

Update: Prison Photography collated a Directory of Photographic & Visual Resources for Guantanamo in May 2009.

Guantanamo Prisoner, Political Graffiti. Banksy

Anyone who says the recent media tour of Guantanamo isn’t a public relations exercise by the lame duck has not had their eyes open. Global media were given a tour of camps 4, 5 and 6 at Gitmo and all the footage was screened and vetted before release.

Video: Here is the Guardian’s three minute offering. With any hope Obama will put this illegal operation out of action in 2009.

Artistic legacy of Guantanamo

Guantanamo Protesters outside the US Embassy, London

Meanwhile, we can think of the potency that the orange jump-suit has gained. It’s another icon of the Bush presidency. With regard it’s establishment and its bare-faced operations, Guantanamo was far outside of the public’s imagination. Our culture stomached the guilt and under the Bush administration it was never likely Guantanamo prison would be brought back into line with international law. Activist and non-activist art protested Guantanamo by subverting the camp’s own visual vocabulary.

UHC Collective. "This is Camp X-Ray". Art Installation, Manchester, 2003. Guards with replica guns were on duty 24 hrs and followed a regime copied from media reports.

Back on my home turf in Manchester, UHC, a notoriously bold and inventive art collective, scaled up a version of Camp X-Ray on an unused lot in Withington. It was complete with guard towers, fake guns and orders and activity that replicated the media’s reports of Guantanamo, Cuba. See other UHC Projects here, and read the BBC report here.

Road to Guantanamo (2006). A Michael Winterbottom Film, Spanish Release

And while we are not focusing entirely on photography, slightly off topic with video, I cannot recommend Road to Guantanamo highly enough. The film tells the ridiculous story of three young British-Pakistanis who were in the wrong place at the wrong time (southern Afghanistan, November 2003), and ended up in Guantanamo for 2 years. Your jaw will not leave the floor.

Herman Krieger – stalwart of the Oregon photography community and Eugene resident – is a self-made specialist in the art of captioning. However, more than his quirky words, I appreciate the great lengths he goes to in order to document sites of the prison industrial complex.

View from Boise Gun Club, New Idaho State Prison. Herman Krieger

Krieger described the circumstances of the series, “The idea of making a photo essay on prisons and their settings came after driving from Tucson to Phoenix. The view of the prison in Florence, Arizona struck me as an odd thing in the middle of the landscape. At that time I was only looking at churches for the series, Churches ad hoc“.

With Lifetime Mortgage, Vacaville, California. Herman Krieger

“I then made some photos of prisons in Oregon and California. Others were made during a trip by car from Oregon to New York. I would have made a longer series, but I was too often hassled by prison guards who noticed me pointing a camera at a prison. They claimed that it was illegal to take a photo of the public building from a public road, and threatened to confiscate my film”, explained Krieger.

Room Without a View, Pelican Bay, California. Herman Krieger

Pelican Bay was opened in 1989 and constructed purposefully to hold the most violent offenders, usually gang members. Along with Corcoran State Prison, in the late 1980s, Pelican Bay ushered in a new era of Supermax facilities in California. They are remote (Pelican Bay is just miles from the Oregon border) and they are expansive. Their distant locations prohibit regular visits from inmates’ family members – a detail probably not lost on the CDCR authorities who sought to transfer, contain and stifle the aggressions of Californian urban areas.

Bayside View, San Quentin, California. Herman Krieger

Having lived in San Francisco for three years, the policies, activities, controversies and executions at San Quentin State Prison were always well reported in the Bay Area press. One of the most frustrating repetitions of the San Quentin coverage was the journalist’s compulsion – regardless of the story – to remind readers of the huge land value of San Quentin and the opportunities for real estate on San Quentin Point.

Open for Tourists, Old State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger.

Over the Hill, New State Prison, Wyoming. Herman Krieger

America is a large country. It should be no surprise that prisons are built in isolated areas – it makes economic sense to build on non-agricultural hinterlands and it makes strategic sense to purpose build facilities on flat open ground. More significantly, to locate these “people warehousing units” out of society’s view, allows convenient cultural and political ignorance for the authorities & citizens that sentenced men and women to America’s new breed of prison.

Krieger’s photographs summarise the key intrigues and detachment “we” feel as those excluded from prison operation and experience. Krieger, in some of his other images, gets closer to the prison walls and yet I deliberately featured these six prints precisely because of their disconnect. What terms, other than those of distance and exclusion, can we legitimately use in dialogue about contemporary prisons?