You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison’ tag.

Andy Kershaw‘s view is a welcome counter to the presumptions of an unknown scenario I and others had considered:

“Most journalists were reporting breathlessly that Port-au-Prince’s main prison had collapsed. Good story. But not for the reasons we were told. The inexperience – and indeed arrogance – of every single reporter who drew our attention to the jail, missed the real significance of its destruction.

It was not that “violent criminals”, “murderers”, “gang bosses” “notorious killers” or “drug dealers” had “simply walked out the front gates”. (And just how did these escapees miraculously avoid being crushed to death in their cells?) Even if true, that was a minor detail to the people of Port-au-Prince, who had more urgent concerns.

The true significance of the prison’s implosion was that it represented for ordinary Haitians, like the wreckage of the presidential palace and the city’s former central army barracks, exquisite revenge upon the prime symbols of decades of state cruelty and oppression.

And many of the prison’s inmates were surely not the dangerous stereotypes of these lurid reports. Haiti’s jails were, notoriously, full of petty thieves and other unfortunates who shouldn’t have been in there anyway. I once had to go into that Penitentiaire Nationale, where I saw hundreds of men kept in cages, without room to lie down, shuffling around literally ankle deep in their own shit, to get out of there the son of a Haitian friend who’d been arrested so that the local police could extort money from his father for the release of his boy.”

via Colin

Currently, truth is also a large casualty in Haiti.

Kershaw’s version is as politically self-serving as most accounts coming out of Haiti, in the confusion following the earthquake citizens, aid-workers and journos are making fast assertions based on their own observations. We should expect that most of these assertions will need modifying in time.

Nevertheless, Kershaw’s is the only commentary that has countered the immediate furor and conjecture surrounding the vacated national prison.

Indeed, Kerhsaw makes it clear that the obfuscations of fact are the direct result of the typical blend of fear and uninformed judgement; judgement applied to prison populations of every nation.

Men rummage through the remains at the Haitian National Penitentiary that stands burnt and empty after a 7.0 magnitude quake rocked Port-au-Prince, in this United Nations handout photo taken and released on January 14. Photo Credit: United Nations, Reuters.

Source

The Port-au-Prince slum Cite Soleil was renowned for extreme violence and as stronghold for gang activity. Recently, activities there had calmed – as Reuters notes, “The pacification of Cite Soleil had been one of President Rene Preval’s few undisputed achievements since taking office in 2006, until the quake devastated Port-au-Prince.”

The National Penitentiary served to incapacitate the capital’s violent gang members and leaders. Between 3,000 and 4,000 former-inmates are now on the streets. The remains and records amid the rubble of the Ministry of Justice have been torched destroying the information needed to track down the former prison population. Law and order are fragile now, but still, violent incidents are few.

Undoubtedly, fear reigns. From the Guardian:

Haiti’s National Penitentiary became an essential apparatus in Preval’s abatement of gang command in Port-au-Prince’s poorer neighbourhoods. In 2004, it is alleged prison administration put down a non-violent protest with lethal force. President Rene Preval’s office argued that they used acceptable force in the interest of self-defense.

But the problem’s in Haiti’s prisons existed long before Preval’s insertion into power in 2004 and even before Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s third stint as president (2001 – 2004).

In 1997, Donna DeCesare won the Alicia Patterson Fellowship and, in 2000, used the opportunity to examine the links between criminal activity, US deportees and gang structure in Haiti.

From looking at her essay I can only presume Preval’s strategic battle with the gangs compounded problems of overcrowding. DeCesare’s essay touches necessarily upon issues of poverty, services, police shortcomings and judicial corruption … all the while following the fortunes of Touchè Caman, U.S. deportee and organizer for Chans Altenativ, an organisation to help Haitian deportees.

Brilliant journalism, but of course ten years old.

More immediately are the concerns of safety and health for Haitians in Port-au-Prince and the surrounding areas.

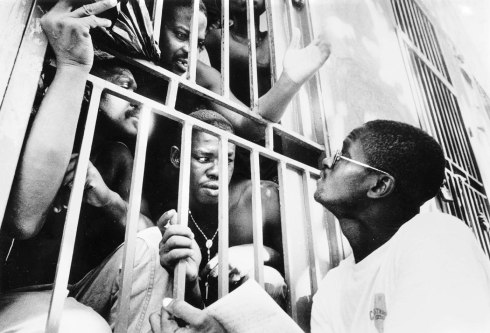

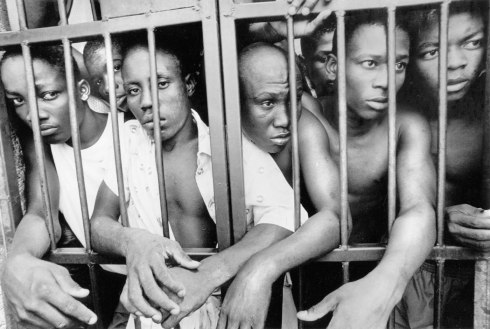

At the Haitian National Penitentiary, Touchè Caman does outreach for Chans Altenativ.looking for deportees among the inmates. “I never thought I’d be going back into a prison after the last time,” he tells me laughing. “It’s a lot different on the other side of the bars. Maybe Chans Altenativ can help a few of them when they get out.” © Donna DeCesare

At Forte Nacional, where children, women and youths are incarcerated, more than 40 youths share the same cell. There are no school classes or trade workshops here. Most of these boys are 16 years old. A few are younger. Some claim membership in Base Big Up and other gangs. One thing is certain, without training or rehabilitative programs of any kind to offer alternatives to street life, many of these boys will find their way into criminal gangs when they are released, even if they weren’t already involved. © Donna DeCesare

Belva Cottier and a young Chicano man during the Occupation of Alcatraz Island, May 31, 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

Today marks the fortieth anniversary of the start of the Indian Occupation of Alcatraz, an action that lasted over eighteen months until June 11th 1971.

Photographic documents of the time are surprisingly scant. Over the past few decades, Ilka Hartmann‘s work has appeared almost ubiquitously in publications about the Indian Occupation. We spoke by telephone about her experiences, the dearth of Native American photographers, the Black Panthers, Richard Nixon, the recent revival of academic research on the occupation and what she’ll be doing to mark the anniversary.

Your entire career has been devoted to social justice issues, particularly the fight for Native American rights. Did your interest begin with the Alcatraz occupation?

No, it began earlier. I came the U.S. in 1964 and that was during the human rights movement. I was a student at the time but I really wanted to go and work with the Native Americans on the reservations of Southern California. I was connected to the Indian community here through a friend who had emigrated to California earlier. I learnt very early about the conditions for American Indians. It reminded my of what I had learnt as a teenager about Nazi rule.

When the occupation began I wanted to go but I couldn’t because I was not Native American, but I waited until 1970.

Concurrently you were photographing the Black Panther movement – centered in Oakland – and the other counter culture movements of the late sixties in the Bay Area. How did they relate to one another?

They were all the same, each group struggling to advertise their conditions, the police brutality and the lack of educational and cultural institutions. I was involved in the fights for American Indians, African Americans, Chicano and Asian Americans in Berkeley. We were protesting as part of the Third World Strike. For me everything was connected and it was the same people who were speaking up later at Alcatraz.

My new book is actually about the relations between the different groups of the civil rights movement. There was a lot of solidarity between groups. The Black Panther Party understood this. Many people think that the Black Panthers were concentrated on their own politics but they understood solidarity and got a lot of help from non-Black people. If you look at my pictures of the Black Panther movement a lot of supporters were the white students of Berkeley. There is a saying, “The suffering of one, is the suffering of everybody”.

In the Bay Area people were so willing to help the Indians at Alcatraz and help in the Black Panther movement and they really felt things were going to change.

I was a student at UC Berkeley and stopped in February 1970. I went to Alcatraz in May of 1970. I had learnt to open my eyes and emotions at UC Berkeley through all the different groups we had.

How many times did you visit Alcatraz during the occupation? And how long did you stay each time?

I only went twice to the island. It is funny because I didn’t even know if my photographs would turn out. I had a camera that I’d borrowed from a friend with a 135 mm Pentax lens … and also a Leica that a friend have given me too. But I didn’t have a light-meter for the Leica so I didn’t know if the photographs I took in the fog would come out. It was so light. I was amazed that they came out. I also went over in a small boat that same year.

So I made contact sheets and tried to get them published which was a big problem because you had to really work on that. My first picture of the occupation was published in an underground paper called the Berkeley Barb then in June 1971 I was at KQED, a Northern California Television station, for an interview with an art editor. I had hitch-hiked there from the area north of San Francisco and I just opened my box of pictures to show him topics I was concerned about when over the intercom came an announcement “The Indians are being taken from Alcatraz.”

I saw some video guys run by, I grabbed my bag and camera and asked them if I could join them. They said, “Yes, ride with us and say you are with us.” We got into an old VW and drove around on the mainland to see the occupiers and that is how I got those shots of the removal. It was an incredible coincidence because I actually lived far from the city. It’s quite incredible. I only went two times during the occupation and then I got those shots afterward.

From then on I made contact with people and in that year I showed my pictures at an Indian Women’s conference, making very good friends with people in the American Indian movement. From then on I went to cultural events, powwows and so on and my pictures appeared in the underground press. I wrote articles and people contacted me for images. That’s how I made the connection.

So really you made no arrangements?

I didn’t make any arrangements. I followed everything from the first day in the papers and on that day in May … on May 30th the Indians asked all the journalists to go and I wanted to be there. That’s how it all started; they invited us there that day.

Did you realize at the time how profound an historical event it was?

Yes, I always felt how important it was. This was the first time they [Native Americans] spoke up. All over the world people wrote about it and the cause became known globally, and especially known in the United States. I believed in it … I still do.

What are your lasting memories of your time and work during the occupation?

It was a prison that had been closed so it was surrounded by barbed wire fence. Some of it had become loose and I took some pictures. The wire swung loose in the air and there was a sound across the island of the wind whispering over it. And if you looked out over the beautiful waters, you really got the sense – with the barbed wire – that the Indians were prisoners, as well as occupiers of the Bay. Prisoners of the Bay; which means prisoners of the World. In that sense I really had a strong feeling of the prison.

How did you react to the environment?

For me, strangely, the experience of going to Alcatraz has always been a very high and wonderful experience. It is hard for me to even explain. Of course I know it was a prison. On the tour of Alcatraz I got very upset, especially during the part when you’re taken downstairs to learn about the lesser known incarceration of Elders and also the cells for those people who didn’t want to go to war. So of course I know it is was a prison, yet when I go there I am struck by exuberance and hope about [Indian] people being able to make statements about their conditions.

I was a witness to that and wanted to be a conduit for those statements. There were no American Indian journalists, we were nearly all white. There was one Indian photographer, John Whitefox, who is now dead. But he lost his film. So we really saw it as our job, politically, as underground photographers and writers to cover what was part of the revolution and social upheaval.

Eldy Bratt, Alcatraz Island, May 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

Two Indian children play on abandoned Department of Justice equipment. Alcatraz Island, 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

San Francisco Bay has a strange history with islands, incarceration and subjugation. San Quentin was the focus of the Black Panther resistance – it is just ten miles north of the city. Angel Island was an immigrations station for Asians – it is known as the “Ellis Island of the West” and some Chinese migrants were kept there for years. And, then there’s Alcatraz. How do you reconcile all this?

It’s totally horrible to me. I come form Germany. Before I came I’d heard about Sing Sing on the river on the East coast. It was a horrible thought to me that they could put people in such prisons.

I drive past San Quentin most days, I have actually been inside and taken photographs. And of Angel Island – it is almost sarcastic to imprison people like that; it’s such a contradiction to the beauty of the Bay. It’s the hubris of human beings to do that to one another.

Of course there are people who should be in prison, like at San Quentin, but certainly the Chinese should not have been treated like that on Angel Island. The Indians and the anti-war demonstrators should absolutely not have been treated like that on Alcatraz. Actually the authorities were respectful to the antiwar demonstrators than they were to the Indians, but still both are an aberration of human nature to treat others like that. I don’t know what to do with murderers but I do know I am against the death penalty.

An Indian man arrives at Pier 40 on the mainland following the removal in June 1971. Indians of All Tribes operated a receiving facility on Pier 40, where donated materials were stored and where Indian people could wait for boats to transport them to Alcatraz Island. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

"We will not give up". Indian occupiers moments after the removal from Alcatraz Island on June 11, 1971. Oohosis, a Cree from Canada (Left) and Peggy Lee Ellenwood, a Sioux from Wolf Point, Montana (Right). Photo © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

How do you see the situation for Native Americans today?

When I started there was said to be one million American Indians and now statistics say there are one and a half million. This is down to two things: first, the numbers have increased, but secondly more people identify as Native Americans where they had tried to hide it before due to racism and prejudice.

I went on one trip with a Native American Family for six weeks across the southwest and I kept asking if the Indians were going to survive and there was some doubt, but now people really think the culture is growing and there has been a notable revival. There advances being made dealing with treatments for alcoholism and returning to free practices of traditional worship. I know that the Omaha are talking of a Renaissance of the Omaha culture. My friend and historian, Dennis Hastings, who was also an occupier of Alcatraz, said to me ten years ago “It could still go either way. Half the Native peoples are debilitated with alcoholism and the other half are vibrant and healthy.”

Great afflictions still exist but there are many more Indians who are able to function in the Western aspects of society and traditional ways of life. When I entered the movement there was only one [Native American] PhD; now there are over a hundred. There is hope now.

What we felt came out of Alcatraz was the influence that it had on Nixon. Because he was a proponent of the war I always used to think of him in only negative ways but that is a learning experience too. It is a shock that someone responsible for the deaths of so many people in the world, of so many Vietnamese, could do something good. He signed the American Indian Religious Freedoms Act (1978). Edward Kennedy also worked a lot on these laws.

We believe the returns of lands such as Blue Lake/Taos Pueblos in New Mexico and lands in Washington followed on from the occupation of Alcatraz. There is a famous picture of Nixon with a group of Paiute American Indians. I believe a former high school sports coach of Nixon’s from San Clememnte was Native American and so we think this teacher influenced him.

As a result of Alcatraz, as well as the land takeovers, the consciousness has been raised among non-Indians and this was very important. People in the Bay Area were very supportive of the occupation, until the point where people were not responsible; it got messy the security got too strong and there were drugs and alcohol. Bad things did happen but in the beginning all that was important to expose to the world was written about, particularly by Tim Findley and all the writers working to get this into the underground press.

Until about 15 years when Troy R. Johnson and Adam Fortunate Eagle wrote and researched their books we didn’t understand everything that had happened – we just knew it was exhilarating. We now have the information of policy changes and the knowledge of people who went back to the reservations; leaders such as Wilma Mankiller who was the principle chief of the Cherokee for a long time. Dennis Hastings was the historian of the Omaha people and brought back the sacred star from Harvard University.

Many people have done things to allow a return to the Native culture and it is so strong now – both the urban and reservation culture. American Indians are making films about urban America – part of modern America but also within their Indian backgrounds. Things have changed enormously.

The benevolence of Richard Nixon is not something I’ve heard about before!

Yes, You can read more about it in our book.

What will you be doing for the 40th anniversary?

I’l be going to UC Berkeley. I’ve been working on an event with a young Native American man who is part of the Native American Studies Program which was established in 1970 as a result of the Third World Strikes. I walked and demonstrated at that time many times. I’m very happy to be returning. LaNada Boyer Means who was one of the leaders of the occupation will be present. We’ll be thinking of Richard Aoki, who was a prominent Asian American in the Black Panther movement, who died just a few months ago.

When these people would lead demonstrations, I would photograph it and then I’d rush to the lab, work through the night to get them printed the next day in the Daily Cal and then have to teach my classes and then take my seminars and it would go on like that for weeks.

So, a young man Richie Richards has organized a 40th Anniversary celebration at Berkeley. It includes events that will run all week, films, speakers, I’ll be showing my slides and then on Saturday we’re going to Alcatraz for a sunrise ceremony. Adam Fortunate Eagle, who wrote the Alcatraz Proclamation, will lead the ceremony on the Island.

In addition at San Francisco State where the 1969 student protests originated their will be a mural unveiled to mark the occasion. There have already been recognition ceremonies for ‘veterans’ of the occupation this week in Berkeley and starting tonight there are events for Native American High School students from all over the area in Berkeley also. Interest has really rekindled recently. The text books have really changed so much and I think that is excellent for younger generations.

And many more to come …

Thanks so much Ilka.

Thank you, Pete.

_________________________________________

For this interview I used Ilka’s portrait shots from the occupation. There are many more photographs to feast on here and here.

Overcoming exhaustion and disillusionment, young Alcatraz Occupier Atha Rider Whitemankiller (Cherokee) stands tall before the press at the Senator Hotel. His eloquent words about the purpose of the occupation - to publicize his people's plight and establish a land base for the Indians of the Bay Area - were the most quoted of the day. San Francisco, California. June 11th 1971. Photo Ilka Hartmann

Wendy Watriss, co-director of Fotofest, really digs Chinese photography. In 2008, Fotofest set up camp in China reaching out for the sakes of diversity, discovery and commerce.

Today, Fotofest announced its International Discoveries II. They include Alejandro Cartagena, Wei Bi, Minstrel Kuik Ching Chieh, Christine Laptuta, Rizwan Mirza, Takeshi Shikama, Kurt Tong, MiMi Youn, and Vee Speers (although Peter Marshall points out Speers isn’t that “new”).

The most comprehensive information available remains the Fotofest Press Release (PDF)

The most tantalising prospect for me personally is Wei Bi. Partly because of his project and partly because there’s nothing out on the web about him.

I skanked this screenshot of the Fotofest website. Sorry FF!

Wei Bi, Untitled, 2008

Here’s the blurb: “Issues of justice are embedded in Chinese artist Wei Bi’s re-staging of his 80–day experience in a Chinese prison — a sentence received for making a photograph. His large black and white photographs are minimal, showing a surreal relationship between near expressionless guards and disoriented prisoners. Despite the constructed nature of his work, Mr. Wei insists his “photography is not aimed to reveal, but to record, recording the existence of my life.” Wei Bi’s work was “discovered” at the Guangzhou 2009 Photo Biennial in Guangzhou, China.”

How can we not be drawn to this work? He was imprisoned for his photography! Potentially, it is a narrative against adversity in which creativity triumphs.

If anyone reading this makes it to the exhibition please get in touch and tell me what you think of Bi’s prison photographs.

It sounds asinine to describe a prison as beautiful. Perhaps, the warm tones of the theatre-house in Kharkiv’s penal colony are a lure. But, I don’t want to budge on this; Maslov’s images are sumptuous.

Let us not forget though, the photographic series, however beautiful, is the product of specific circumstances. The more we know about these circumstances the better equipped we are to understand them and their content. Last week, Sasha and I talked over Skype about the details of the project.

How did you arrive upon the subject?

I had a couple of friends who had been running a theatre class in a prison in Kharkiv, Ukraine. I thought it was a great subject so I went along. Theatre performers aren’t what you expect to see in a prison. Being an actor is a ridiculous notion for criminals; you’re basically putting yourself in the position of the fool. The prison was maximum security so they were in there for serious crimes. At the beginning it was … kind of creepy, but then I got used to it.

I wanted to shoot with film. Initially, the warden said I’d have to use digital equipment, but I explained it was essential I used film and showed him some of my images. In the end, he permitted it.

It looks like you were you there for the final performances. How long had they been rehearsing and how many times did you visit?

They’d been working on the play for 9 months. I went in three times, but most of the shots from the project were taken on the day of the main performance.

What message did you hope to communicate with the project?

I go into all projects very open, without really knowing what it’s going to be like and if I will actually have anything at all in the end; what can I see? What can I tell? I think this is best.

Some of your subjects seem uncomfortable with the camera?

Yes. It is understandable as cameras aren’t something they are used to. Some don’t want to be seen for obvious reasons. Those acting in the troupe were more open to being photographed. I felt like during the new experience for them with this theatre they opened new horizons, but generally in prison the feeling is that the camera is not your friend.

I actually tried to shoot in two prisons, they other being a women’s prison but nothing came out of that project. The women acted very differently around the camera. Every time they saw the camera they’d change something. They’d usually smile. They would present themselves for the camera. The women always smiled. Once, I caught a glance of a female prisoners glaring at a male guard. It was a real wolf glare. I lifted the camera, but instantly she saw me and changed her look. Her eyes became those of kittens.

Perhaps this desire to perform or adapt for the camera by female prisoners is something you could work with in the future? Deborah Luster worked with the females in the Louisiana prison system making portraits of them in full theatrical costumes.

Yes, it would be interesting to shoot there again. But also, people aren’t totally truthful. They can’t talk about things that are difficult. I wasn’t allowed in their cells. The experience changed me. Not massively, but it did make me look at things a little differently.

In Ukraine can one assume certain things about the prison population? I ask this because in America’s medium security prisons where men can be serving long to life sentences, some may not be there because they are violent offenders. It is the non-violent men who are warehoused who seem to lose most through harsh sentencing. Does this mix of offender-types occur in Ukraine?

I cannot say. Of course, I never asked. One inmate did say to me, “You don’t have to pretend to respect me. You know I am in here because of something terrible I did.” But, I wasn’t pretending to respect anyone. These people were new for me, if you don’t consider the place where the [project] took place you are not able to form any prejudice.

Do you know what percentage of the men would eventually be released?

No, but I know some were due to be released very soon. One actor was due to be released one day before of the performance, but he preferred to stay for another week so that he could perform the show.

Right before show began I took a shot of a woman in the audience. I will never forget this moment. Later I found out she was a mother of one of the inmates in the troupe. She had come to tell him that his brother had died on the outside. She waited until after he’d finished the show because she didn’t want to ruin his performance. It was only afterward when I found this out I understood why she did not smile during the show.

And how was the show?

The dramatics were amazing to see. Many of the men struggled over and above their usual habits to get the lines out. The play was The House that Swift Built, which is a fiction about a house full of ridiculous items and fantastic people. Jonathan Swift tells unbelievable stories and plays practical jokes, the nature of existence in and outside the house is questioned. The players have the potential to transform their lives. Of course it was interesting to see this done by prisoners.

Still, many of the lines were delivered with arrogance. Even in soft conversation, the actors came across as brash. They are used to being in a defensive position so there was always a strange arrogance … or little aggression.

Did the inmates see your prints?

Yes, I sent prints to the prison. If there was a shot with two prisoners in it, I’d send two copies. I don’t know how they divided all the works among the guys but I know they got them.

Did you ever have to secure model release forms?

[Laughs] No. I only had to agree on the project with the warden. The fact my friends had been there a while also made my case easier. The warden was forward thinking by Ukrainian standards. He was interested in the publicity it would gain for his prison.

What are the general thoughts of prisons among the Ukrainian public?

That they are places you shouldn’t go. Prisons are tough everywhere. After you get out, you just have a new set of complexes.

How do former-prisoners fare in Ukraine? For example, ex-prisoners in the US have to petition to gain their right to vote back. How does it compare?

Ukrainian prisoners can vote in prison. But, more generally, prison is forever a stain on your character. Human rights violations occur in prisons all the time – stabbings, abuses of power by the guards. You hear about these things on the news. But these instances are just pieces of sand on the beach. It could be a much larger problem. Perhaps it is but we don’t hear about it.

Well, it is an amazing glimpse for us all to get at an arts program inside a Ukrainian prison. What equipment did you use?

I shot with a Kiev 6S, a 6×6 medium format camera. It is bulky and heavy. I really liked working with it but I was always very visible to the prisoners with this thing in my hands. And the sound that it makes is beyond any politeness.

What comes next?

I have two things on. I have just got back from Donbass, a region in Eastern Ukraine where I was doing a story on coal miners. It was an amazing experience, because for 20 years nothing has changed there except dramatic decline of population. There are small towns that lived off coal mines in Soviet period, but many mines were shut down or there are places where 5-6 thousands people worked and now there are 50-70 miners. It’s sad and fascinating area. The story will be out in a few weeks. I am also working on a show of photographic portraits for a gallery in Ukraine.

How do you pick your subjects?

I do what I think is important. I don’t plan too far ahead. I’ll be interested to see what happens in the near future with the industry.

You heard this month about Christopher Anderson saying, “The death of journalism is bad for society, but we’ll be better off with less photojournalism. I won’t miss the self-important, self-congratulatory, hypocritical part of photojournalism at all. The industry has been a fraud for some time.”

I didn’t but he could be right. There are trends in photography. When the trends change, there seems to be two types of response. The first is to chase and feed the trend. The second is – in the uncertainty – to stick to what is valuable to you, and that will usually be something you like. The best work will always come form that second approach. And as for the market; the market is like the ocean. It can change three or four times a day. There’s no use in trying to predict that.

True. Thanks Sasha

Thank You.

Sasha Maslov has shown this work before at Vewd and at his Lightstalkers profile.

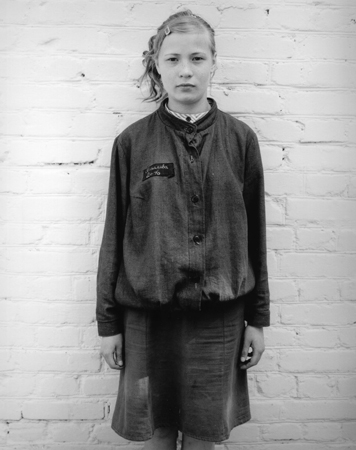

Untitled, Juvenile Prison Alexin, Russia 2003

Ingar Krauss traveled to places in the former Soviet Union, and made portraits of children the same ages, but living in state-run orphanages, juvenile prisons and camps. Many of these kids are not criminals but these “childhood institutions” are the only places society can find for them. (Jim Casper, LensCulture)

A couple of stand-out quotes from Krauss (also from LensCulture):

I recognized that I am especially interested in those children who already have a biography — orphans or criminal children. They have already a story to tell. They seem to be responsible in a way which is not childlike.

and

Looking at those pictures they seem always to ask: Why me? And in fact this is usually the first question they are asking when I am choosing from 200 orphans in an orphanage, this one or these two. And all I can answer them is that I recognized them, that I feel I know them. Not personally, of course, because I don’t know their stories the moment I decide who I would like to photograph, but in a fundamental way I think I know them.

Untitled, Juvenile Prison Rjazan, Russia 2003

Untitled, Juvenile Prison Alexin, Russia 2003

Untitled, Juvenile Prison Rjazan, Russia 2003

Ingar Krauss has also trained his lens on seasonal workers and economic migrants in Europe. His work from different series is collected in the book Ingar Krauss: Portraits.

Dread Scott‘s 2004 Lockdown pairs portraits with audio statements from the prisoners. The stories intend to represent the two million-plus inmates in American prisons. Dread’s belief is that America is defined by its criminal justice system and its incarcerated masses. This is not a position I would query.

Ostensibly, Lockdown is a less confrontational work than his renowned What is the Proper Way to Display the U.S. Flag? (1988) but the strength of the polemic, from which it stems, is no less.

Dread has drawn strong support as well as well-publicised contempt for his art and politics. Even the most respected progressive voices in politics, theory and photography have paused to question the coherence of his work. Dread, I trust, would expect no less than strong reaction to his work.

Among other identifiers, Dread is an avowed Maoist. He has stated, “This is a world where a tiny handful controls the great wealth and knowledge humanity as a whole has created.” In America more than any other ‘developed’ nation this statement applies. Dread’s political statement must be taken as delivered and used as the departure point for this work.

For our interview, I wanted to focus on Dread’s efforts and successes in accessing prisons, drawing testimony and mounting the piece. And to find out why these efforts were necessary.

Q & A

PP: How many prisons/jails did you visit while making Lockdown?

DS: I visited one prison and I went to another where I was turned away at the last minute. I also worked with some youth who had been in the system, but were not locked up at the time I photographed and interviewed them. This is also true of one adult ex-con I worked with.

PP: How many portraits are in the series?

DS: There are eleven that I show. Obviously I took more, but there are eleven that are good. I also would like to expand the project but I have no plans to do this at the moment.

PP: Did you choose the sitters or did they choose you?

DS: In most cases the prison chose them and told them that a photographer wanted to do a project involving prisoners. Then once I met with them I discussed more about the project and most of them wanted to be part of it.

PP: Were there prisoners who were simply not eligible for participation in Lockdown? If so, for what reasons?

DS: I wanted to get a somewhat broad sampling of the prison population. In many respects this was achieved, but because I was unable to work on the project as extensively as I would have liked, some types of prisoners aren’t in the project. For example, I didn’t get to any women’s facilities, any jails and I was not to visit any prisoners on Death Row.

PP: Did you ever photograph a prisoner having had no prior contact or discussion?

DS: Generally this is how the project was done – I would be introduced to them and photograph them in the same day.

PP: Who controlled the length of time you had to introduce your project to, and work with, each of the sitters?

DS: Ultimately, it was the prison that controlled the hours of the visit and how many I would be allowed. But once that was set, I could spend as much or as little time with any one prisoner.

PP: How did you organize yourself and your subjects during the projects as a whole? What forms did the communication take before, during and after the sitting for the photograph?

DS: With rare exception, I wasn’t able to communicate with the prisoners before the photography/interview session. The sessions were very intensive. I generally wasn’t able to spend more than an hour with each prisoner. Often I only had about 40 minutes so the work was done quickly. I would start by discussing what I was trying to do with the project and let them know that I wasn’t working with the prison and in fact that I was a revolutionary and I felt that the whole system was worthless. Which is not what the project was about but I wanted them to know where I was coming from. If after knowing more about me and the project they wanted to participate, we would move forward.

Generally, I would then photograph them and then I would interview them, which in many ways was just a conversation. As a preface to the interview I would say something like “It’s clear that the main requirement to get into jail today is that you be poor and Black or Latino. Who is in jail? I need to learn your story and want to tell it. Many people don’t know. And those that do know, people like you and your family aren’t talking about it enough. I need the truth. What happened? How did you end up here? I want to put faces on the slaves of these prisons, which are like modern day slave ships that don’t float.” Then we did the interview. As for more communication after the session, unfortunately the prison that I was working with made this impossible. I sent photographs of all the prisoners to them and I wrote again thanking them for participating. I never heard back from anyone. What I later learned when I met one of the prisoners when he was on the outside, he said that neither he nor anyone else ever got any photo or letter from me.

PP: How do you deal with impartiality?

DS: I am not impartial. I think that this is an unjust society and has exploitation woven into it’s very fabric – a society where a tiny handful control the wealth and knowledge that humanity as a whole has created. The imprisonment of two million+ people shines a lot of light on the society as a whole. I wanted to bring to light the people that are latterly hidden from society broadly and make a work that presented portraits of these hidden people and brought of out the insights they have about the society that imprisons them. Because these people and there ideas are written out of the popular discourse in society, I think that this project can reveal a lot about the society as a whole. The prisoners express their individual views and don’t necessarily share all of mine, but through the work as a whole, an audience has the opportunity to grapple with a lot about the foundations of this society and see and meet people who have a lot to say about it.

PP: What reasons did each of the inmates have for taking part? Were their reasons opinions that you also held or had previously held?

DS: Many of the prisoners initially met me because it was a break from their daily routine. Some were intrigued by the change and chance to work with some sort of photographer. Most didn’t know much about the project prior to meeting me. But once they met me they mostly decided to participate because they wanted to have both their individual story put out in the world, but also they saw this as a chance to be part of a broader conversation about a country that imprisons over two million people. There was also a small minority who were looking for some angle to shorten their time or hoped I was a vehicle to communicate with people outside.

PP: Did you take many pictures of the same sitter? Did the inmates of each portrait have a say in which print you chose for exhibition?

DS: Yes, I generally took about 20 pictures of each person. Sometimes a few more and occasionally less. Because the prison prevented me from communicating with them, they weren’t able to have any input into the portrait that I used.

PP: James Clifford has said, “Represented voices can be powerful indices of a living people – more so even than photographs, which, however realistic and contemporary, always evoke a certain irreducible past tense.” How important to this piece are the audio tracks; the ‘represented voices’ of the inmates?

The audio is essential. It is as much part of the project as the photographs and I will not exhibit the work without the audio. One thing that I wanted to do with Lockdown is bring the faces, voices and ideas of those who are hidden behind bars in the gallery and museum setting. People throughout society need to see who is imprisoned and know what insights they have in the world. So there is an important level of the ideas. But there is also a question of voice. It is very specific and allows the audience to encounter the prisoners in a much more real and complex way.

PP: Did each inmate prepare a statement or do you edit audio in post-production from single unrehearsed dialogues?

DS: The audio is carefully edited from much longer interviews. The interviews typically were about 30-40 minutes. And the audio in the work uses about 3-6 minute excerpts.

PP: How do you describe the relationship between the collected raw data (first-hand spoken testimony; photographic documentation; a unique name/identity) and the cultural frame you set it in (gallery, public space, political statement)?

DS: The portraits and interviews form the basis for the work but the art, once it is exhibited is just that – art. The art would be inconceivable without the photos and interviews, but they have been selected & edited and assembled to be a coherent work of art.

PP: Does your artistic voice compete with the oral testimonies/voices of the men you photograph?

DS: While the testimonies of the individuals are important as an individual expressions, Lockdown is the opinionated view of its author. I am not mischaracterizing any of the individual stories, but I have put them within the overall meditation on a society that imprisons over two million people that is Lockdown. So my voice dominates on a certain level. The work is really the collective voices and photograph, not the individual stories. It is made up of individuals, but I think that the whole adds up to more than the sum of the parts. It is because of this, the way the work is structured overall, that it is not a “documentary” where one person’s story is next to their photograph and it is about all of the individuals. It is about what they, through the work as a whole, address as a group.

PP: About your work, you have said, “the continuum of history is a recurring theme in many of my works” and therefore inviting comparisons between past and present events. Do you use artistic devices, photographic or otherwise, to assist the viewers with these comparisons?

DS: Yes, but I don’t see the continuum of history as being so foregrounded in this work. Some of my projects will have a lynching paired with police brutality or an electric chair. This isn’t so much the case with this work. Though I did decide to make the portraits black and white which roots somewhat in the past and situates the theme of the work as being tied to a longer history as well as roots the project in a certain photographic tradition.

PP: Are you following a photographic tradition? If so, which elements of past photographic works inform Lockdown. If not, where then should people find their visual cues for reading the photographs?

DS: In making this work, I really appreciated Danny Lyons’ Conversations with the Dead. My project is different but it is on this continuum. Also, Avedon’s In the American West. Again, I’m doing something different. I think Avedon is exoticizing his subjects a bit, but they are really great portraits and he does reveal things about the people he shoots that many outside of the culture don’t know about. Meat packers and guys on oil rigs aren’t often part of Chelsea conversations. Also, Roy DeCarava’s influenced this work. Particularly how he respected many of the people he photographed. As the project is not just a photo project, I drew on other artistic traditions. Actually the text and image work from the 80s has informed me on works like this. I just use audio text rather than written. What I am doing is new, but it wouldn’t exist without these influences.

_______________________________________________________________

Dread Scott works in a range of media including installation, photography, screen printing, video and performance. Dread first received national attention as a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1989, President Bush Sr. declared his installation What is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag? “disgraceful,” and the entire US Senate denounced the work when they passed legislation to “protect the flag.” As part of the popular effort opposing compulsory patriotism, he, along with three other protesters, burned flags on the steps of the US Capitol. This resulted in a Supreme Court case and a landmark decision.

In 1992, Dread was a fellow at the Whitney Independent Study Program. In 1995, he was awarded a Mid Atlantic\National Endowment for the Arts Regional Fellowship in Photography. In 2000, he participated in the Institute on the Arts and Civic Dialogue directed by Anna Deavere Smith at Harvard University. He has been awarded a Mid Atlantic/NEA Regional Fellowship in Photography, a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Sculpture (2001) and Fellowship in Performance Art/Multi-disciplinary Art (2005), and a Creative Capital Foundation grant. In 2000 he participated in the Institute on the Arts and Civic Dialogue directed by Anna Deavere Smith at Harvard University. That year he also worked on a Special Edition Fellowship at the Lower East Side Printshop.

His work has been exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the New Museum of Contemporary Art, Robert Miller Gallery in New York, Brooklyn Museum, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum and the DeBeyerd Center for Contemporary Art in the Netherlands. His public sculptures have been installed at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, New York and Franconia Sculpture Park in Minnesota.

In 2008, the Museum of Contemporary African Disporan Art in Brooklyn, NY hosted Dread Scott: Welcome to America.

This interview provides more extensive coverage of Dread Scott’s oeuvre and politics.

Klavdij Sluban and Jim Casper of LensCulture talked about Klavdij’s photography workshops in juvenile prisons across the world.

Early in the interview, Klavdij discloses his personal sadness that prisons exist. This emotion may be raw but it is not naive; Klavdij is balanced and realistic about what he can achieve with a camera in these specific distopias. He also says in seven words what I established this blog to say “Jails are a world to be discovered.”

He went to the prisons not as photographer, but as a concerned citizen. He realised if he were to go inside it would need to be with some reciprocity … so he took cameras and used them.

In terms of engagement and commitment to a population – the youth prison population of the world – Klavdij Sluban could and should be considered a ‘Concerned Photographer’. He deserves that loaded epithet.