You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prison’ tag.

Joseph Rodriguez‘s work is essential. If I and others can promote his photography humanity then we’ve done some good.

Last week PDN ran a post about the value of the “Digital Curator“. It was a well threaded argument about things we already know: that if an online presence (blogger) does his/her thing for long enough and with a consistent (their own) voice they’ll begin to garner readers, respect and influence.

[WARNING: link blitz, but all justified]

Thankfully, we have (I believe) a healthy photography blogosphere in which plenty of photographers present their own STUFF; megaliths go vernacular; academics question and answer; fine art specialists point us in the direction of good practice & theory; insiders offer editorial, publishing, gallery, collector, buyer or industry viewpoints; universities promote; non-profits take new angles; curmudgeons grumble; old media gets hip; young guns splash out with collective and interview projects & some hover untouchably above.

In September, duckrabbit joined the fray. You may know already, but I am a fan of duck’s blog (by Ben Chesterton). I am not a fan because I agree with everything Ben has to say, but because he says it without frills and then will spend the time necessary to engage the consequent discussions. Such commitment is a priceless commodity.

duckrabbit deals primarily with photojournalism and multimedia and so Ben’s coverage doesn’t always dovetail with the preoccupations of other photographic genres – which is fine, we all have our favourite corners.

To get to the point. I am nodding furiously toward the coverage of Joseph Rodriguez on duckrabbit for three reasons:

1) Because Rodriguez (along with Leon Borensztein) made me realise how vital the relationship between photographer and subject is in creating images. Rodriguez is worth more time than duck or I could ever commit.

2) Because this is the latest in principled stances duckrabbit has taken, AND it happens to highlight the stories of formerly incarcerated.

3) Because I am committed to writing more about Rodriguez in the next month … and need to let you know.

duckrabbit’s first feature of his new series ‘Where It’s At’ (stuff that kicks a duck’s arse) is Rodriguez’s work on Re-entry after prison. Rodriguez worked with Walden House (I remember fondly the stained glass of the San Francisco WH, Buena Vista Park). As duckrabbit puts it, “Rodriguez records lives lived and he never measures the lives of those he shoots against a photographic award, magazine spread or advertising contract. His eye is never on the future, it is always in conversation with the now.”

Go to duck’s post and watch Rodriguez’s 7 minute multimedia piece on re-entry. California is where I cut my teeth in the prison policy and prisoners’ rights fields, so for me, it is especially resonant … and vital.

Also worth noting is Benjamin Jarosch, Rodriguez’s current assistant.

While we are on the topic of different realities in urban America, keep an eye out for this film at your local cinemaplex indie-theatre.

In the next few weeks I’ll be making comment and whirring the brain cogs over Rodriguez’s photographic endeavour Juvenile Justice . Stay tuned.

Rodriguez has won acclaim from all the important people that need to take notice, including Fifty Crows, which incidentally started up a blog recently. Everyone reading this should follow Fifty Crows because they support photographers who get in knee deep … and then some.

Peace.

San Pedro Prison in Bolivia has ceased tours for foreign visitors.

I regret my one missed opportunity. I’d been mildly obsessed with the La Paz prison for a couple of years before I arrived outside its gate and got turned away. That was July, 2008. I had read in Lonely Planet it was a piece of cake to get in and get a tour. Apparently not in my case. I surmise, that I had experienced the beginning of the end for La Paz’s most bizarre tourist attraction.

It’s definitely over now. This from yesterday’s Guardian;

Tours have never been officially recognised and the vagaries of securing visiting privileges for foreigners stems from the fact that prison guards have different rules/corruptions and relationships to outside ‘tour-guides’. Basically, foreigners had to be lucky or connected to get inside.

Flickr searches prove that “wide-eyed travellers” have visited in all the months since my failed attempt.

The reason for the end of this bizarre tourist ritual? Seemingly, tourists got too cocky and too brazen. The new prison warden ended the debacle. This was a peculiar decision (on first glance) given years of international coverage and tolerance by the authorities, but basically, everyone involved had become too comfortable – objectionably so – with the institution-turned-circus.

The group most guilty for giddy spectacle was of course the tourists. In February the self-titled “Wild Rover Group” posted this video.

And it was the tipping point. The video doesn’t show anything that wasn’t commonly known, but it spells it all out with clarity and (critically) to an unrestricted worldwide audience.

This thorough dissection of the events by a Bolivian source, explains;

It is surprising that a single video should be the tipping point, especially after a decade of widely circulated photographs. Nevertheless, the circus could no longer be ignored, nor controlled.

Interest online was mirrored by interest on the ground. Tourists filled the square outside wishing to visit; such numbers could no longer be surreptitiously ghosted in the side-door.

Vicky Baker explains,

Here’s the local media shining a big spotlight on activities with long-overdue questioning and coverage of the tours. Foreigners reacting to the attentions, flipping off the camera and scampering away under jackets were only ever going to look bad!

Unrest

Governor, Jose Cabrera, is emphatic, “The prisoners have to understand that this is a penitentiary.”

The tourism, while exploitative, was a reliable source of revenue for the prisoners and their families. By shutting down the tours, incomes for over a 1,000 men, women and children was dragged out from under them.

San Pedro was/is indelibly tied to society outside. Family members come and go daily to bring goods and services to the self-made micro-economy. The decision to close the tours down was exacerbated by new restrictions on visiting privileges. Discord grew.

As the Bolivian news crews were present to film the hoards of foreign tourists in the square, they captured the three hours of unrest from start to finish. Families, including children, of the prisoners were caught in the tear gas clouds. Unfortunate scenes.

The riot was a predictable end point to the new warden’s crude (but probably) necessary shut-down of this dubious spectacle. Many Bolivians didn’t like the fact the nation’s biggest prison was a site of titillation for foreign visitors; many were understandably ashamed and angered.

Paradoxically, one of the factors that allowed mass visitation was the accommodation of family members to spend unlimited amounts of time with incarcerated husbands & fathers during daylight hours. The institution had a generous (and unAmerican) protocol for the relaxed coming and goings of non-inmates.

What Next?

Money and the necessities it brings are key to solving the tensions. According to a prisoner interviewed by La Rázon, “70% of the [250 peso] fee goes to the police and the people who organize the foreigners for the tours,” the rest being split up among prisoners. This monetary ecosystem may not have been fair but it was consistent.

The new warden has since negotiated and agreed new rules for San Pedro, presumably taking into account the stymied income for all inside. Time will tell. As an indication of how fragile authority is at the prison, the new warden has adopted a fast rotation of guards to prevent foreigners … the suggestion being, a guard needs only to get comfortable at his gate post before he can start manipulating bribes to get tourists in again.

I’ll leave you arguments for permanent closure of San Pedro to foreigners with the thoughts of two Bolivians;

and

True.

The Remains

The photographic legacy is wide and varied. Amateur snaps prevail here, here, here and here. Enthusiasts occasionally turn their skills, and professionals such as Hector Mediavilla have focused on cocaine manufacture and drug addiction in San Pedro Prison.

If I ever have kids I’ll read them Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine at bedtime. I’ll use Klein’s words as proxy for my own in imparting the necessary cautions of governments and guns in our f*#ked up world.

(Hold up, there’s reason enough why not to have kids.)

Chapters two and three deal with the growth of Chicago School economics and its pernicious experiments and infiltration into the ‘Southern Cone’.

Throughout the 60s and 70s, the US & the CIA facilitated right-wing opposition movements, juntas, military coups and consequent torture programs in Chile, Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina.

During this time between 100,000 and 150,000 people were killed or ‘disappeared’. Estimates are wide and varied because the murders were out of control, accountability suspended and the terror doled out faster than it could be monitored.

During the Dirty War in Argentina, the terror of each night repeated the previous; a seven-year state-sanctioned massacre that bled into every neighbourhood under the cover of darkness.

The inhumanity is incomprehensible, but Klein attempts to describe the various methods used at times by different forces in each of the countries. Uruguay had a particular penchant for isolation;

Prisoners in Uruguay’s Libertad Prison were sent to la isla, the island: tiny windowless cells in which one bare light bulb was illuminated at all times. High value prisoners were kept in absolute isolation for more than a decade.

“We were beginning to think we were dead, that our cells weren’t cells but rather graves, that the outside world didn’t exist, that the sun was a myth,” one of these prisoners, Mauricio Rosencof, recalled. He saw the sun for a total of eight hours over eleven and a half years. So deprived were his senses during this time that he “forgot colors – there were no colors.”

(Page 93)

In a foot-note Klein remarks:

‘The prison administration at Libertad worked closely with behavioral psychologists to design torture techniques tailored to each individual’s psychological profile – a method now used at Guantanamo Bay.’

We are all agreed: Michael Jackson’s death is a sad event. Firstly because he was young, secondly because he runs through our cultural DNA and thirdly because we never really managed to fully understand him.

Jackson’s life and work were wrapped up in the confuddling of race and the obliteration of its prerequisites for discussion. I am not talking only about his self-manipulated skin colour. I am talking about the fact he was accused of antisemitism for contested lyrics in the 1996 release They Don’t Really Care About Us and the fact he was accused of exploiting the poor of Rio de Janeiro for its music video.

This song is only one time Jackson was simultaneously cast as victim and perpetrator by the media and public all making use of his eccentricity to grind their own agendas.

The controversy led Jackson (for the only time in his career) to film a second video for one of his songs, taking his crotch grabs off the favela streets and into the prison chow hall. One or both of the versions was banned by MTV – I am not quite sure, but it doesn’t matter.

Jackson threw enough contorted imagery at these two videos to satisfy a life’s worth of political action. The prison version is a montage of famous photojournalist and media images; death, natural disaster, street brutality, Vietnam napalm, hate crimes, Rodney King, African pestilence, riots, nuclear detonation and the Ku Klux Klan?

I am undecided as to how Jackson’s convolution of imagery helps an informed debate on inequality in society. How much does a famine of the 80s in an unnamed African nation have to do with US urban riots?

It should be said, that for his manic prison tableaux, Jackson did accurately reflect reality in the casting of a disproportion number of men of colour.

Lee Grant contacted me a few months ago to tell me of her project Belco Pride – an institutional portrait of the now empty Belconnen Remand Centre. ‘Belco’ was a small facility designed for 17 people, but according to Lee housing approximately 70 toward the end. Officially, the capacity is/was “under revision”.

The remand prisoners have since been relocated to the Alexander Maconochie Centre, which is talked up as Australia’s first prison built in accordance with the Geneva Convention (more on that in a later post).

After inmate rehousing, but before total closure, Grant took another opportunity to tour the facility, “thanks to an open day … billed, believe it or not, as a family event. And the families were out in force …”

Therefore, I was happy to see Lee post a few of her images from the ongoing series. I particularly liked these two pairings which are a wry juxtaposition.

Shortly thereafter my enjoyment turned to bafflement.

In Lee’s description of the open day she mentioned that the phrase “Arbeit macht frei” was clearly visible to all arriving visitors. This flat out shocked me. On Lee’s blog, I commented,

There is no correlation between Nazi concentration camps and modern Australian prisons. The inclusion of the phrase is confusing and offensive.

I had originally mistaken the facility, thinking the quote was on view at an opening for the new prison and not, as the case was, a closing of the old. Still, wonder remains at this crude and ill-advised allusion.

Lee responded;

[I will be sure to post any developments – be they images or elaborations on this peculiar alignment of geography, phrase and history.]

Like Lee, I do not want to judge individuals working in Corrective Services. Instead, I’ll simply say that systems in which workers operate along lines of strict procedure are likely to harbour casual and offensive attitudes. Workers are as disciplined as inmates in all prisons. So when individuals are subject to a system – relieved of actual decision making – there is no incentive to challenge objectionable attitudes.

For the best of the rest, check out Lee Grant’s Op Shop series, which proves that you can change the country and you can change the moniker (charity shop, UK; thrift store, USA) but the look, personnel, wares and atmosphere remain the same.

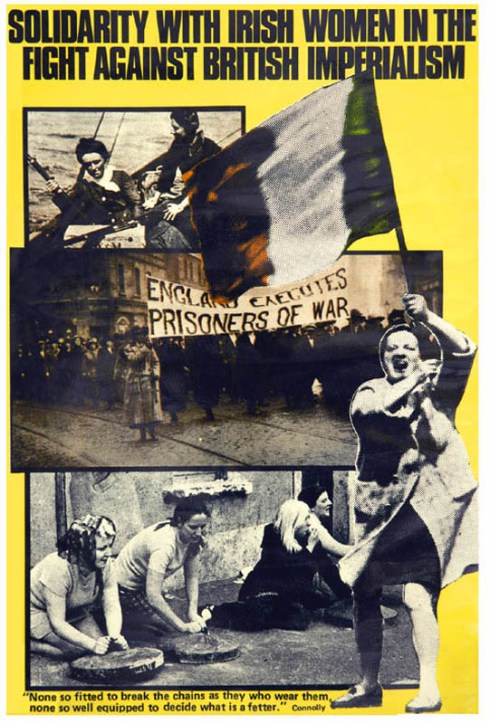

The inspiring Just Seeds Collective which peddles art to fund prison rights activism pointed me via its blog toward the Poster Film-Collective of London.

The Poster Film-Collective is a unique archive of graphics for African, Cultural, International, Irish, British and Women’s causes. With direct politics and robust graphics, poster arts are a nostalgic favourite for many art historians.

‘The Troubles’ of Northern Ireland are a very difficult topic for me to discuss; but not because I am close or emotionally compromised and not because I know or knew anyone involved. I grew up just the other side of the Irish Sea, but Belfast may as well have been the other side of the world to me. I was raised Catholic and my Mum’s family are from the Republic of Ireland. Yet, as a child my family rarely discussed the situation in Northern Ireland. Even in 1996, when the IRA bombed the Arndale shopping centre in Manchester (just down the M61 from my home town) the conflict was still too abstract and ancient for my teenage mind to comprehend.

I think any political labels or alliances that would fall upon my family were deflected by a distant dismay at the violence of the time. ‘The Troubles’ of Northern Ireland are not something I feel comfortable idealising; rather limply I retreat to the cliche that one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter. All sides (there were more than two) were guilty of arrogance, obstinacy and extreme violence. The ideological brutality played out on the streets was matched by that meted out in the prisons, most notably Long Kesh, later renamed The Maze.

It is a lingering guilt for me that ‘The Troubles’ have always been historical … historicised. It is this guilt that accounts for the fact I’ve not before discussed Donovan Wylie’s The Maze on Prison Photography. Wylie is saturated in Irish history – it is his life’s vocation. On the other hand, I would be a fraud if I attempted to summarise the complex events of a physically-close-culturally-distant conflict.

It is with similar guilt I refer readers – in the first instance – not to news reports or academic reflection but to a 2008 film. But, I do so because Steve McQueen’s Hunger is a breath-taking portrayal of a life-taking episode in the history of Maze prison. It is a wonderful observation of British prisons, Irish Republican solidarity and inmate management in the face of political protest.

McQueen, in his directorial debut, specialises in long uninterrupted shots which grip time (and all its anguish) and forces the politicised narratives through the mangle. He flattens and simplifies the visuals drawing out the incredible fragility of human skin, snow-flake, fly, lamb, ribcage … McQueen is surely a great photographer too.

Through Donovan Wylie’s work I learnt of Dr. Louise Purbrick’s excellent continuing research “concerned above all with the meanings of things and how those meanings are contained or revealed, experienced and theorised.” Purbrick wrote the essay for Donvan Wylie’s book, Maze. That was in 2004. In 2007, Purbrick extended the survey, jointly editing the book Contested Spaces. It analysed the “divided cities of Berlin, Nicosia and Jerusalem, the borderlands between the United States and Mexico, battlefields in Scotland and South Africa, a Nazi labour camp in Northern France, memorial sites in Australia and Rwanda, and Abu Ghraib.”

Purbrick worked with another academic Cahal McLaughlin on the oral history & documentary film project Inside Stories featuring Irish Republican Gerry Kelly, Loyalist Billy Hutchinson and ex-warder Desi Waterworth. And it is here I start (and I encourage you to start), with personal testimony when trying to understand ‘The Troubles’.

Donovan Wylie has continued his visual archaelogy of Irish history with Scrapbook.

Born in Belfast in 1971, DONOVAN WYLIE discovered photography at an early age. He left school at sixteen, and embarked on a three-month journey around Ireland that resulted in the production of his first book, 32 Counties (Secker and Warburg 1989), published while he was still a teenager. In 1992 Wylie was invited to become a nominee of Magnum Photos and in 1998 he became a full member. Much of his work, often described as ‘Archaeo-logies’, has stemmed primarily to date from the political and social landscape of Northern Ireland.

Born in Belfast in 1971, DONOVAN WYLIE discovered photography at an early age. He left school at sixteen, and embarked on a three-month journey around Ireland that resulted in the production of his first book, 32 Counties (Secker and Warburg 1989), published while he was still a teenager. In 1992 Wylie was invited to become a nominee of Magnum Photos and in 1998 he became a full member. Much of his work, often described as ‘Archaeo-logies’, has stemmed primarily to date from the political and social landscape of Northern Ireland.

LOUISE PURBRICK is Senior Lecturer in the History of Art and Design at the University of Brighton, UK. She is author of The Architecture of Containment in D. Wylie, The Maze (Granta, 2004) and, with John Schofield and Axel Klausmeier, editor of Re-Mapping the Field: New Approaches to Conflict Archaeology (Westkreuz-Verlag, 2006). She also works on the material culture of everyday life and has written The Wedding Present: Domestic Life beyond Consumption (Ashgate, 2007) (Source)

CAHAL McLAUGHLIN is Senior Lecturer in the School of Film, Media and Journalism at the University of Ulster. He is also a documentary filmmaker and is currently working on a Heritage Lottery Funded project, ‘Prison Memory Archive’.

Admittedly, Wordsworth was a Romantic English poet of the Victorian Age with some highfalutin ideals and a penchant for a Christian God. But he also had some pretty radical ideas about the health of the human soul being dependent on its environment.

“Heaven lies about us in our infancy! Shades of the prison-house begin to close upon the growing Boy.”

Along with the dirt and the consolidation of British class frameworks, the industrial revolution also ushered in the politics of institutions and discipline. Wordsworth lamented a society in which the economies of labour stacked the odds against the young and unschooled.

The prison was a notion of culture; as visible in the cities as it was felt in the soul. Piers Lewis summarised it as such:

Got any conventions or received ideas you’d like to take the opportunity to shed?