You are currently browsing petebrook’s articles.

Everybody in Portland knows about the recent closure of Newspace Center for Photography. Those beyond the city might not, but they can imagine the damage to the photo community when one of the last accessible darkrooms for film shuttered almost overnight. A hole was left.

I was very fond of Newspace. I’m not a photographer so never used its darkroom facilities but its active lecture series and artist-in-residence program brought many great practitioners to town. It was also the final venue for Prison Obscura in Spring 2016. (Installation shots). I’ve fond memories of the staff, support, volunteers, openings and exhibitions at Newspace. A hole was left.

There’s a larger backstory to the saga, some raw emotions and accusations that better board planning could’ve averted the disaster. But instead of focusing on ‘What if’ or ‘What might have been’ a core group of photo-geeks sunk their efforts, cash and hope into creating a replacement. They showed up at Newspace’s fire-sale of equipment, snagged as much as they could and loaded it onto a flotilla of trucks. They’ve built out a brand spanking new darkroom and are ready for business. Introducing The Portland Darkroom.

The Portland Darkroom wants to keep film photography alive and accessible. Rose City needs this resource. They’ve launched a Kickstarter campaign to help fund the first year of operations and get them off to a running start.

I can’t wait to get in the space and meet the photo-peeps who’ve made this happen. Who knows, maybe I’ll resurrect the Eye On PDX series I did with Blake Andrews 2012-2014 to celebrate, and ask questions of, our local image-makers?

Head over to The Portland Darkroom website and sign up for updates. Place some money in the pot. Go on! In return for your support, there’s prints, workshops, stickers, postcards and oodles of thanks from the founders. Head over to The Portland Darkroom Kickstarter page and check out the perks.

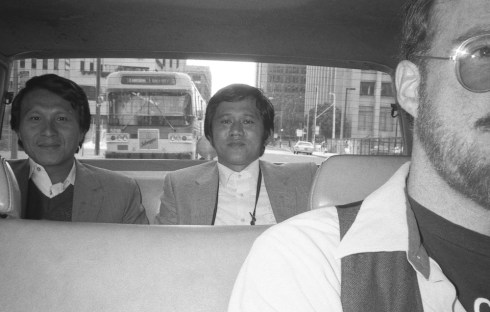

I learnt about Bill Washburn‘s series Taxi years ago (on a recommendation from Blake Andrews). The pictures stuck with me, especially during a recent two-year stint living in San Francisco. Now I’m back in Portland and Bill Washburn is my neighbour and I’m so happy to have been able to write about Taxi for Timeline: These vivid 1980s photos show gritty San Francisco cab life in the days before Uber.

“As a taxi driver, I had a very privileged viewpoint,” says Washburn who drove a cab between 1982 and 1986 to supplement his income during art school. “It was an opportunity to get to know San Francisco intensely. It was a dynamic city, I worked it all, not just downtown.”

Washburn’s unorthodox portraits are strange nostalgic triggers for a city we may not have known then but know now, through daily headlines, of a city drastically changed by decades of housing market spikes, mass displacement and gentrification. There’s loss as well as discovery in these photos.

I asked Kelly Dessaint, cab-driver, San Francisco Examiner columnist and author of I Drive SF, what he thought of Washburn’s images.

“It’s always a mystery who’s going to climb in the back of your taxi,” says Dessaint. “The uncertainty of where a ride will take you can be exhilarating and terrifying. Sometimes simultaneously. These photos really capture the randomness of taxi driving, as well as the awkward intimacy that comes from sharing an enclosed space with a stranger for a prolonged period of time.”

Dessaint, who drove for both Uber and Lyft before signing up with City Cabs, laments the loss of spontaneity and unpredictability brought on by ridesharing

“With app-based transportation,” he explains, “the pick up and drop off points, along with the route, are recorded. You know the passenger’s name before they get in the car. They know yours. It’s not a random encounter like when someone flags you on the street. And with the rating system, the passenger is always in control. Drivers know that if they step out of line, they can easily get deactivated. Which limits spontaneity and creates a passive experience for the driver. As a taxi driver, you’re always in control.”

The power of these photos may lie in the fact that they show conversation not merely transaction; that they depict a time before profiles, stars and likes. For Washburn, now in his seventies, the differences and decisions are obvious.

“I’ll never take an Uber or a Lyft. I’d feel like a traitor,” says Washburn.

See more and read more here.

For my first piece for Timeline, I put a spotlight on a collection of mugshots, rediscovered and researched by artist Shayne Davidson. This adds to a her research of hundreds of antique mugshots depicting shoplifters, grifters, counterfeiters, “a wife murderer”, pickpockets and many more.

Made by the St. Louis Police Department between 1857 and 1867, the archive, held at the Missouri History Museum, comprises the oldest extant examples of mugshots in the U.S. Davidson has compiled many of the portraits into a new e-book Captured and Exposed (More).

Quote:

It’s hard to imagine U.S. law enforcement today without its wealth of tracking and surveillance technologies. From facial recognition to the databases being populated with drivers’ license photos of non-criminal citizens, from police scanners tracking all mobile devices in a five-block radius to lampposts that are listening in, federal investigators and police departments nationwide have never had more tools to capture images, scrape data, and monitor movements of people.

But these “smart” technologies (and the laws that allow their use) have developed only relatively recently, and incrementally. It’s not always been so sophisticated. A hundred and fifty years ago, shortly after the invention of photography, some police departments began making images of convicted criminals.

Read the full piece and see more portraits: America’s Oldest Mugshots Show the Naked Faces of the Downtrodden, Criminal and Marginalized

KNIVES, BY JASON KOXVOLD

In 2004, the Schrade Knife factory in Ellenville, NY closed its doors for the last time. Operations were moved to China and, almost overnight, 500 locals lost their jobs. Suppliers and services in the area lost business too and the towns of Ellenville, Napanoch and Wawarsing where photographer Jason Koxvold lives have had to adapt to avoid massive economic injury. In 2015, Koxvold began documenting his hometown and its residents. Since the closures of factories in this pocket of the Hudson Valley, Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch is the biggest employer in the town.

The project Knives, says Koxvold, “serves as a microcosm of the larger issues facing the United States, grappling with the effects of automation and outsourcing, cuts in services, and the rise of identity politics.”

It includes portraits of prisoners, employees and former prison officers. The motif of the knife functions as a literal description of a disappeared economy and identity marker for the people of Wawarsing, but it also acts as a metaphor to the silent violence of both globalisation and incarceration. Whereas a gun mows people down in a hail of bullets, a knife cuts through and guts with a quiet, single swift action. The damage can be deep, precise. An unspectacular assault that is so often lethal.

I admire the way Koxvold has gone about peeling back the layers of his home-region. He managed to gain access into the local prison photographing prisoners. Without trying, he found many locals who had worked in the prison. He often picked up visual threads that ended up looping back to the fact of incarceration.

Koxvold is currently crowdfunding monies for the photobook Knives. We chatted about how the prison industrial complex manifests itself in his work, how it functions in the community and how exactly he got inside.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Do prisons work?

Jason Koxvold (JK): As a Norwegian citizen, my answer would be yes. As a permanent resident of the United States, my answer is not as well as they should.

With that said, during the making of this project I’ve become aware of the work of the Bard Prison Initiative, and programs like that are to be applauded; but in general in this country, it’s my understanding that prisons are seen as a punishment more than an opportunity to rehabilitate. That approach is unsustainable.

PP: You’re crowdfunding to raise money for Knives book. There’s no mention of the prison in the Kickstarter video but you’ve explained to me that the prison is “woven more deeply through the work than uncaptioned photographs might suggest.” Can you flesh that out a bit?

JK: Because the prison has been a feature of the town for so long, and there weren’t many other opportunities for employment in the region, it turned out that some of the men I photographed for this project had worked as prison guards for large portions of their lives.

Specifically, one of the characters had worked in a prison for 25 years, and possessed a wealth of knowledge about the place. His is the knife with “JUSTICE” engraved into the blade, which seems perverse in some regard; he’s written comments on internet forums defending the use of the phrase “Nigger Chaser” in the name of a knife. So this history of the application of violence is etched deeply into the soul of the town, even as it now finds itself emasculated and adrift.

PP: At what point did Eastern Correctional Facility in Napanoch become a subject in Knives?

JK: Fairly early on in my research it became clear that it would be impossible to ignore it.

PP: Why is the prison was important?

JK: The prison looms over the town in some way; it’s an imposing, gothic style building that can be clearly seen from all approaches, despite being a secretive location. At first – not knowing much about the penal system here – I was under the impression that the prison housed inmates from the region, and assumed that would include some former Schrade employees, but primarily they are from New York City. That also changes the makeup of the town to some degree, as spouses and families move to the area to make visitation less onerous.

PP: What did you do to depict the prison?

JK: I made portraits of three men inside the prison, and some exteriors of how the prison relates to the landscape and the town around it.

PP: What did you do to connect (or not) with those incarcerated and working there?

JK: My initial outreach was to the NYS Department of Corrections public affairs office, to explain my project and what I hoped to achieve. I wrote letters to a group of inmates, outlining my idea and asking if they would like to participate.

PP: You say Knives raises more questions than answers. I like it when you say you’re interested in ambition, failure, hubris. But still, it seems like the failure for us to imagine a different but improving future leads people to think that jobs might come back, and I think that accounts for Trump’s appeal in the Rust Belt. Whether he could spark an impossible resurgence or not, matters less than the fact he promises he will. As best as you can estimate, what is the future for Wawarsing?

JK: The town is working to turn things around; tourism, which was a huge business in the Catskill region in the middle of the 20th century, is what people are pinning their hopes on, and the area has seen considerable growth in that regard in recent years. There’s a great theatre, Shadowland Stages, that produces several plays a year. For some time there was talk of a new casino, but ultimately another town won the bid. In place of that, there’s now a multimillion dollar sports complex in the works.

PP: What difficulties or successes did you encounter while pursuing a narrative about Eastern Correctional Facility?

JK: My original intent included making portraits of prison guards and interiors of the prison, specifically with the intent of drawing contextual lines between this secure, sanitized inner environment and the world outside, but I was limited to the visiting area and employees were off-limits.

Even determining who was currently incarcerated at Eastern was challenging; I had to file a Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) request, which operates under an archaic system. After some correspondence, I scheduled visits to make portraits of three inmates, not knowing what they would look like or what to expect; they were very patient and generous with their time.

JK: Interestingly, photographing the exterior of the prison was more challenging than getting inside. I tend to be quite specific about weather for my exteriors, but DOCS doesn’t necessarily have the infrastructure for rapid approvals of media visits, and certain areas that I strongly wanted to photograph were absolutely off limits.

PP: What are local attitudes toward the prison?

JK: My sense is that there’s a grudging acceptance of it. People probably wish it was elsewhere, but at the same time it provides jobs for the town.

PP: You grew up in Britain. Do you see the U.S. in a particularly different way?

JK: I grew up around Windsor and Egham, but I’ve spent the whole of my adult life in the United States. I formally arrived a few months before 9/11, and unfortunately, I think that terrible event achieved its goal. 15 years of war – which is the subject of my other major project, currently in progress – has changed the country radically for the worse, in my opinion.

PP: What next for the work?

JK: My intent is to have the book ready to go to press quite rapidly after the Kickstarter is complete; it will include some new images that haven’t been shared before; and some of the work will be shown at the Davis Orton Gallery in June and July.

PP: Good luck, Jason. Thanks for chatting.

JK: Thank you.

BIO

Jason Koxvold (b. 1977) is a fine art photographer based between Brooklyn and Upstate New York. Follow his activities through his website, Instagram, Twitter and Vimeo.

Support the Kickstarter for the Knives photobook.

Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly announces the opening of the Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement office on Wednesday. Susan Walsh/AP

–

I haven’t the time to flag every callous and legally-questionable move made by the Trump administration (no-one has) but the establishment of the cynically-titled Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement (VOICE) office stands out as a deplorable act of race-baiting, even by Donald’s standards.

The office, which states its purpose as that to assist victims of crimes committed by immigrants, is a in fact a vehicle for Trump’s continued propaganda against immigrants.

Victims of all crimes need assistance. Given that there are fewer victims of crimes by undocumented persons than there are victims of crimes by citizens–because immigrants (documented and undocumented) commit crimes at a lower rate than citizens–VOICE doesn’t even make sense; it pours resources toward a small subset of post-crime law enforcement response.

Trump is demonising immigrants, casting them as dangerous and a threat. This is a lie. Data shows that immigrants are less likely to commit crime, especially violent crime.

The law should function in a way to sanction against all crimes, in all places, perpetrated by any persons against any persons in the same way. Law enforcement should not be advertising, annotating and publicising crimes by a specific group. To do so is the abandonment of impartiality, the abandonment of a key function of the law. To do so is tyranny.

A response from the Immigrant Justice Network landed in my inbox this morning. I’d like to share it.

After 100 hundred days of losing in the courts, legislature, and before the global community, the Trump administration has hit a new low in its attempt to validate an indefensible platform built on racial hatred, fear-mongering, and public deception. The administration has failed to secure credible sources to support its racist claims about immigrants and crime. While the administration has had to resort to inventing lies or “alternative facts” on other issues, with today’s formal launch of the VOICE initiative by DHS, the Trump administration has hit a new low in its exploitation of human loss to serve its own narrow interests.

Operating on the same racist logic that has fuelled the country’s discriminatory policing and mass incarceration of people of colour, VOICE is a shameful propaganda vehicle whose sole aim is to promote fear, social divisions, and the myth of *immigrant criminality*. It says as much about the President’s attitudes towards immigrants as it does about his views towards everyday Americans, whom he thinks he can frighten into passive complicity.

VOICE has no place in our society. As a network that fights for the civil, human, and legal rights of all immigrants, the IJN vehemently denounces this shameful exploitation of tragedy for political advantage.

— Signed Mizue Aizeki (Immigrant Defense Project), Angie Junck (Immigrant Legal Resource Center), and Paromita Shah (National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild) on behalf of the Immigrant Justice Network (IJN)