You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

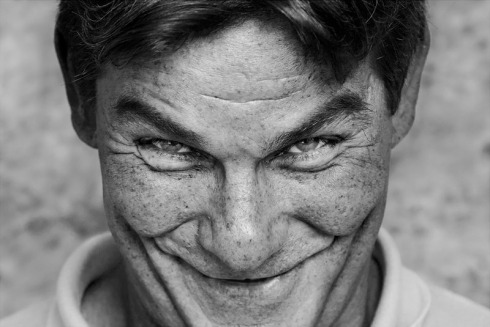

“Tex Johnson, 60” by Ron Levine, courtesy of the artist.

Later this week, I’ll be attending the inaugural prison arts and activism conference, Marking Time.

Hosted by the Institute for Research on Women at Rutgers, and across multiple venues, the event brings together an incredibly committed and skilled cohort of practitioners throughout many disciplines — from dance to yoga, from occupational health to sculpture, and from film making to social work.

I’ll be moderating a panel discussion Imagery and Prisons: Engaging and Persuading Audiences, with Gregory Sale, Lorenzo Steele, Jr., and Mark Strandquist on Wednesday afternoon. In addition, a version of Prison Obscura will be on show at the Alfa Art Gallery in downtown New Brunswick.

To emphasise the breadth and depth of expertise I’ve copied out the schedule below. I have made bold and linked the names of artists, activists and academics’ names with whose work I am already familiar … and admire.

I pepper the post with artworks made by photographic artists attending Marking Time.

Marking Time runs 8th-10th Oct. Registration for the conferecne is free.

See you in New Brunswick this Wednesday?!?!

“Allen and Tanasha, 1998.” Family album. Courtesy of the Fleetwood family.

WEDNESDAY 8TH OCT.

Session 1: 9: 30 – 10:45 am

PANEL: Creative Arts and Occupational Health (ZLD)

Susan Connor and Susanne Pitak Davis (Rutgers University Correctional Healthcare) “Finding Meaning Thru Art”

Karen Anne Melendez (Rutgers University Correctional Healthcare) “The Concert Performance with Adult Females in Correctional Health Care”

Moderator: Michael Rockland (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

WORKSHOP: Steps Taken: Footprints in the Cell (NBL)

Rachel Hoppenstein (Temple University)

Ann Marie Mantey (Temple University)

Session 2: 11:00 – 12:15 pm

PANEL: Law, News, and Art (ZLD)

Regina Austin (Penn Law School)

Ann Schwartzman (Pennsylvania Prison Society)

Tom Isler (Journalist/Filmaker)

Moderator: Tehama Lopez

WORKSHOP: Utilizing Dance as a Social Tool: Dance Making with Women in Prison (NBL)

Meredith-Lyn Avey (Avodah Dance)

Julie Gayer Kris (Avodah Dance)

LUNCH: 12:15 – 1:15 pm

Session 3: 1:15 – 2:30 pm

PANEL: Imagery and Prisons: Engaging and Persuading Audiences (ZLD)

Gregory Sale (Artist)

Lorenzo Steele, Jr. (Founder, Behind these Prison Walls)

Mark Strandquist (Artist)

Moderator: Pete Brook (Freelance Writer/Curator)

PRESENTATION: The Political and Educational Possibilities of Exhibitions (NBL)

David Adler (Independent Curator)

Sean Kelley (Eastern State Penitentiary)

Rickie Solinger (Independent Curator)

Session 4 2:45 – 4:00 pm

PANEL: About Time (ZLD)

Damon Locks (Prison and Neighborhood Arts Project)

Erica R. Meiners (Northeastern Illinois University/Prison and Neighborhood Arts Project)

Sarah Ross (School of the Art Institute of Chicago/ Prison + Neighborhood Arts Project)

Fereshteh Toosi (Columbia College Chicago)

Moderator: Donna Gustafson (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

PANEL: Best Practices: Arts, Prisons and Community Engagement (NBL)

Robyn Buseman (City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program)

Shani Jamila (Artist, Cultural Worker, Human Rights Advocate)

Kyes Stevens (Alabama Prison Arts and Education Project)

EVENING EVENTS

4:00 – 5:00 pm Artist Talk: Jesse Krimes (ZLD)

5:00– 5:45 pm Welcome Reception (ZL)

7:30 – 9:00 pm Opening Keynote: Reginald Dwayne Betts (KC)

Welcome Remarks: IRW Director Nicole Fleetwood

Introduction of Keynote: Dean Shadd Maruna, School of Criminal Justice – Rutgers, Newark

“Exercise Cages, New Mexico” by Dana Greene, courtesy of the artist.

“That Renown New Mexico Light” by Dana Greene, courtesy of the artist.

THURSDAY OCTOBER 9TH

Session 1: 9: 30 – 10:45 am

PANEL: Theater in Prisons (ZLD)

Wende Ballew (Reforming Arts Incorporated, Georgia) “Theatre of the Oppressed in Women’s Prisons: Highly Beneficial, Yet Hated”

Lisa Biggs (Michigan State University) “Demeter’s Daughters: Reconsidering the Role of the Performing Arts in Incarcerated Women’s Rehabilitation”

Karen Davis (Texas A&M) “Rituals that Rehabilitate: Learning Community from Shakespeare Behind Bars”

Bruce Levitt and Nicholas Fesette (Cornell University) “Where the Walls Contain Everything: The Birth and Growth of a Prison Theatre Group”

Moderator: Elin Diamond (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

PANEL: Prison Architecture, Space and Place (NBL)

Svetlana Djuric (Activist) and Nevena Dutina (Independent Scholar) “Living Prison”

Maria Gaspar (Artist) “The 96 Acres Project”

Vanessa Massaro, (Bucknell) “It’s a revolving door”: Rethinking the Borders of Carceral Spaces”

Moderator: Matthew B. Ferguson (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

Session 2 11:00 – 12:15 pm

PRESENTATION: Sustaining Engagement through Art: The US and Mexico (ZLD)

Phyllis Kornfeld (Independent Art Teacher, Author, Activist, Curator) “Thirty Years Teaching Art in Prison: Into the Unknown and Why We Need to Go There”

Marisa Belausteguigoitia (UNAM) “Mural Painting in Mexican Carceral Institutions”

WORKSHOP: The Arts: Essential Tools for Working with Women and Families impacted by Incarceration (NBL)

Kathy Borteck-Gersten (The Judy Dworin Performance Project)

Judy Dworin (The Judy Dworin Performance Project)

Joseph Lea (The Judy Dworin Performance Project)

Kathy Wyatt (The Judy Dworin Performance Project)

LUNCH: 12:15 pm – 1:15 pm

Session 3 1:15 – 2:30 pm

PRESENTATION: Visualizing Bodies/Space: A Performative Picture of Justice System-Involved Girls & Women in Miami, FL (ZLD)

Nereida Garcia Ferraz (Artist/Women on the Rise!)

Jillian Hernandez (University of California-San Diego/Women on the Rise!)

Anya Wallace (Penn State University/Women on the Rise!)

Moderator: Ferris Olin (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

PANEL: 25 Years of the Creative Prison Arts Project: Connecting Incarcerated Artists with the University of Michigan Community (NBL)

Reuben Kenyatta (Independent Artist)

Ashley Lucas (University of Michigan)

Janie Paul (University of Michigan)

PRESENTATION: The Art of Surviving in Solitary Confinement (RAL)

Bonnie Kerness (American Friends Service Committee Prison Watch Program)

Ojore Lutalo (American Friends Service Committee Prison Watch Program)

“Theda Rice, 77” by Ron Levine, courtesy of the artist.

Session 4 2:45 – 4:00 pm

PANEL: Restorative Arts and Aging in Prison (ZLD)

Aileen Hongo (Educator/Activist)

Anne Katz (University of Southern California)

Ron Levine (Artist)

WORKSHOP: The SwallowTale Project: Creative Writing for Incarcerated Women (NBL)

Angel Clark (Photographer/Filmmaker)

Bianca Spriggs (Artist/Poet)

Session 5 4:15 – 5:30 pm

PANEL: Resisting Guantanamo through Art and Law (ZLD)

Aliya Hana Hussain (Center for Constitutional Rights)

Matthew Daloisio (Witness against Torture)

Aaron Hughes (Independent Artist)

Moderator: Joshua Colangelo-Bryan (Dorsey & Whitney LLP)

WORKSHOP: Bar None: The Possibilities and Limitations of Theater Arts in Prison (NBL)

Max Forman-Mullin (Bar None Theater Company)

Julia Taylor (Bar None Theater Company)

EVENING EVENTS

5:45 – 6:45 pm Reception (NBL)

7:00 – 9:00 pm: Artist Talks: Russell Craig, Deborah Luster, Dean Gillispie, Jared Owen (AAG)

“Self Portrait” by Russell Craig, acrylic on cloth, 2014, courtesy of the artist.

“LCIW, St. Gabriel, Louisiana, Zelphea Adams” from One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana, by Deborah Luster, courtesy of the artist.

FRIDAY OCTOBER 10TH

Session 1: 9: 30 – 10:45 am

PANEL: Prison Lit (ZLD)

Helen Lee (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) “Eldridge Cleaver’s SOUL ON ICE: A Rhetoric of Confrontation in Prison Writing”

Suzanne Uzzilia (CUNY Graduate Center) “Lolita’s Legacy: The Mutual Imprisonment of Lolita Lebrón and Irene Vilar”

Carolina Villalba (University of Miami) “Radical Motherhood: Redressing the Imprisoned Body in Assata Shakur’s Assata: An Autobiography”

Moderator: Monica Ríos (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

PANEL: Photographic Education Program at Penitentiary Centers in Venezuela: From the Lleca to the Cohue (ZMM)

Helena Acosta (Independent Curator)

Violette Bule (Photographer)

Moderator: Katie Mccollough (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

PANEL: Narrating Injustice: Youth and Mass Incarceration (BSF)

Sean Saifa M. Wall (Independent Artist) “Letters to an Unborn Son”

Richard Mora and Mary Christianakis (Occidental College) “(Re)writing Identities: Past, Present, and Future Narratives of Young People in Juvenile Detention Facilities”

Beth Ohlsson (Independent Educator) “Reaching through the Cracks: Connecting Incarcerated Parents with their Children through Story”

Moderator: Annie Fukushima (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

Session 2 11:00 – 12:15 pm

PANEL: Gender, Sexuality, and Systemic Injustices (ZLD)

Michelle Handelman (Filmmaker, Fashion Institute of Technology) “Beware the Lily Law: Tales of Transgender Inmates”

Tracy Huling (Prison Public Memory Project) “‘She was incorrigible…’ Building Public Memory About A Girl’s Prison”

Carol Jacobsen (University of Michigan) “For Dear Life: Visual and Political Strategies for Freedom and Human Rights of Incarcerated Women”

Moderator: Simone A. James Alexander (Seton Hall University)

“Beware the Lily Law” by Michelle Handelman, high-definition video, sound, Installation at Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia. Photo credit: Laure Leber, 2014.

PANEL: Life Sentences: Memoir-Writing as Arts and Activism in a Maximum Security Women’s Prison (ZMM)

Courtney Polidori (Rowan University)

Michele Lise Tarter (The College of New Jersey)

Samantha Zimbler (Oxford University Press)

Moderator: Fakhri Haghani (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

PANEL: The Politics of Imprisonment (BSF)

Dana Greene (New Mexico State University) “Carceral Frontier: The Borderlands of New Mexico’s Prisons”

Marge Parsons (Prisoners Revolutionary Literature Fund) “Free the Spirit from Its Cell”

Jackie Sumell (Independent Artist) “The House That Herman Built”

Treacy Ziegler (Independent Artist) “Light and Shadow in a Prison Cell”

Moderator: Angus Gillespie (Rutgers-New Brunswick)

LUNCH: 12:15 pm – 1:15 pm

Session 3 1:15 – 2:30 pm

PRESENTATION: Shakespeare in Prison (ZLD)

Tom Magill (Educational Shakespeare Company Ltd)

Curt Tofteland (Shakespeare Behind Bars)

PANEL: Building Effective Prison Arts Programs (ZMM)

Laurie Brooks (William James Association) “California Prison Arts: A Quantitative Evaluation”

Jeff Greene (Prison Arts Program at Community Partners in Action) “Beyond Stereotype: Building & Supporting Extraordinary Arts Programs in Prison”

Becky Mer (California Appellate Project/Prison Arts Coalition) “National Prison Arts Networking in the US: Lessons from the Prison Arts Coalition”

Moderator: Lee Bernstein

PANEL: Genre and Aesthetics in Prisons (BSF)

T.J. Desch Obi (Baruch College, CUNY) “Honor and the Aesthetics of Agon in Jailhouse Rock”

Anoop Mirpuri (Portland State University) “Genre and the Aesthetics of Prison Abolition”

Jon-Christian Suggs (John Jay College, CUNY) “Behind the Red Door: Real and Fictional Communism in Prison”

Ronak K. Kapadia (University of Illinois at Chicago) “US Military Imprisonment and the Sensorial Life of Empire”

Moderator: Jed Murr

Session 4 2:45 – 4:00 pm

PANEL: Twenty Years of Teaching Visual and Literary Arts in a Maximum-Security Prison (ZLD)

Rachel M. Simon (Marymount Manhattan College in Bedford Hills Correctional Facility)

Duston Spear (Marymount Manhattan College in Bedford Hills Correctional Facility)

WORKSHOP: Alternatives to Violence Workshops in Prison: Liminal Performances of Community and/as Activism (ZMM)

Chad Dell (Monmouth University)

Johanna Foster (Monmouth University)

Eleanor Novek (Monmouth University)

Deanna Shoemaker (Monmouth University)

WORKSHOP: More Than a Rap Sheet: The Real Stories of Incarcerated Women (BSF)

Amanda Edgar (Family Crisis Services)

Jen LaChance Sibley (Family Crisis Services)

Jenny Stasio (Family Crisis Services)

CLOSING REMARKS (ZLD): 4:00 – 4:30 pm

OPENING RECEPTION FOR PRISON OBSCURA (AAG):4:30 – 6:30 pm

EVENING EVENTS: 7:00 – 9:30 pm (SH)

Tales from the Cell, Mountainview Program

The Peculiar Patriot, Liza Jessie Peterson

Women on Our Own, acapella group of formerly incarcerated musicians

Films to be shown all day on October 9 & 10 at the Ruth Dill Johnson Crockett Building, 162 Ryders Lane (Douglass Campus), schedule to be determined.

—————————————————-

Key for venue codes:

AAG: ALFA ART GALLERY

BSF: BLOUSTEIN SCHOOL FORUM

KC: KIRKPATRICK CHAPEL

NBL: NEW BRUNSWICK PUBLIC LIBRARY COMMUNITY ROOM

RAL: RUTGERS ART LIBRARY

SH: SCOTT HALL

ZL: ZIMMERLI MUSEUM LOBBY

ZLD: ZIMMERLI MUSEUM LOWER DODGE GALLERY

ZMM: ZIMMERLI MUSEUM MULTIMAX ROOM

——————————————————-

Photographer Milcho Pipin went into the Central Penitentiary of the State of Paraná, in Curitiba, Brazil. It’s a fairly sizable prison with nearly 1,500 prisoners.”Despite frequent overcrowding problems and precarious infrastructural condition, this penitentiary is by no means the worst in Brazil,” says Pipin.

From within this tough institution, Pipin wanted primarily to “capture expressions of male and female prisoners and to understand and share their feelings,” he says.

In collaboration with Dr. Maurício Stegemann Dieter, a criminology specialist, Pipin produced the series Locked Up. Both answered a few short questions I had.

Scroll down for Q&A.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Why did you want to photograph in Central Penitentiary of the State of Paraná?

Milcho Pipin (MP): It all started because of my father. He was a police inspector of foreign crime / border control in Macedonia for 30 years. He went through a lot of cases. His sense of comprehensibility to all social classes inspired me to photograph in prison.

PP: What are attitudes toward prisons and prisoners in Brazil?

Dr. Maurício Stegemann Dieter (MSD): Hostile and cynical.

PP: What do Brazilians think of incarceration in the U.S.?

MSD: Except for some researchers (criminology and criminal law professors, mostly), they don’t have a clue.

PP: What did the staff think of you and your camera?

MP: As the director of the prison informed us, it had been over 40 years since media had access inside, it was pretty shocking to me. That’s why when we entered, the staff was not really sure who we were, how we got there and what was our purpose being inside with a photo equipment.

I explained that there was nothing to do with any political purpose and that it was an artistic project only — to photograph the lives behind those concertina wires. Later, the staff mood changed and they were really helpful showing around the prison and introducing us to the prisoners.

PP: How long can babies stay with their mothers? Until what age?

MSD: From birth up to 6-months. After that, they meet daily for up to 4 hours.

PP: Of the 1480 prisoners, how many are men and how many are women?

Maurício Dieter (MD): 1116 men and 364 women, each in a separate penitentiary.

PP: What did the prisoners think about your photography?

MP: The first day was the hardest. We had a short briefing with the prisoners about the project and I felt their lack of interest as they were not yet sure that we were not there for political purpose.

I explained [to a large group] that the only thing I wanted to do was to take their portraits as they expressed their feelings, and then to show the outside world. Most of them left the briefing, just 7 or so stayed.

I showed my print portfolio to those who stayed and I heard one prisoner saying: “Oh good, ok, let’s do this!” As I started photographing one by one, they spread the news and the interest to have their photo taken became viral in the next days. Almost all of them were friendly with us, with a few exceptions.

PP: Did the prisoners see your photos and/or receive prints?

MP: They saw the photos on the camera display a few moments afterwards. I gave them my website link, so the family could see them online. I did promise prints though, and for sure they will soon receive them. There are still a lot of photos in a finalizing phase so I can start printing and delivering them with pleasure to all the prisoners that collaborated in this project.

PP: Milcho, how do you hope your photographs might alter attitudes?

MP: Hmm, through my photographs I hope people will be able to visualize, feel and understand that we are all at the risk of committing a crime, purposely or not, at any moment of our lives, and of being convicted and facing a sentence. That’s why we should appreciate our freedom, because it’s just one of those big things we usually don’t appreciate until we lose it.

We never know, our future is a dice.

FIN

BIOGRAPHY

Milcho Pipin was born in Bitola, Macedonia. Based in Curitiba, Brazil, Pipin started photography in 2001 as he journeyed across five continents. He focuses on editorial, commercial, documentary and fine art photography. Pipin is founder and creative director of VRV, international creative agency.

All images: Milcho Pipin, and used with permission. Use, manipulate or alteration of any photo without written permission of Milcho Pipin is prohibited.

D’Juan Collins tries on a shirt at Goodwill in Harlem, NY on Feb. 14, 2014. D’Juan was charged with drug possession and spent 6 years of an 8-year sentence in prison. He was released in July 2013 and is currently in a custody battle with the New York foster care system for his 7-year-old son, Isaiah.

INTRODUCING PHYLLIS DOONEY

Often when I want to publish images I want to add thoughts of my own and, in all honesty, direct the message a little. Today’s feature is an exception. Photographer Phyllis Dooney approached me with a complete pitch and story. From the issue to the subject, from Dooney’s motivation to her text and images, there is nothing I can add. This piece is entirely Dooney’s.

The series titled Collapsar follows D’Juan Collins who served six years in a New York State Prison, during which time he lost custody of his son. He’s done everything within his power to reestablish a stable life and yet the prospect of losing his son permanently looms larger than ever before.

D’Juan Collins goes to the local branch of the New York Public Library in the Bronx, NY on Dec. 16, 2013. D’Juan is there to get on the internet, a service his 3/4 housing does not provide. He has launched www.saveisaiah.com to raise awareness for his issues with the foster care system and to raise funds.

COLLAPSAR

Words by Phyllis Dooney.

“You need a man to teach you how to be a man.”

— Tupac Shakur, Tupac: Resurrection

D’Juan Collins wants to be an active parent in his son Isaiah’s life. At the same time, D’Juan realizes that fatherhood, in the form of genuine leadership, nurturing and daily guidance, is a challenge for him. His three-quarter housing is not a fit home for his son. D’Juan needs more income than his job, selling tickets in Times Square, can amount to.

D’Juan is a 44-year-old black man from inner-city Chicago, who now resides in the Bronx. Like his absent father before him, D’Juan both used and sold drugs as a psychological and economic solution. Eventually this behavior landed him in prison. In July 2013, D’Juan was released from prison after serving six years of an eight-year sentence for possession of crack-cocaine.

D’Juan shopping for ties at Goodwill in Harlem, NY on Feb. 14, 2014. D’Juan has a job interview as a paralegal and is shopping for appropriate clothing.

Isaiah Fischer-Collins, 7, plays with his paternal grandmother, Dianna Collins, and uncle in a hotel room in Brooklyn, NY on Dec. 21, 2013. Dianna was granted visitation rights from ACS to spend holiday time with her grandson for the weekend. However, Dianna is not an approved visitation supervisor by ACS which means that when she looks after Isaiah the family remains fractured because D’Juan cannot be present as well.

D’Juan joins forces with the organization Fostering Progressive Advocacy in a protest on the steps of City Hall in New York, NY on April 16, 2014. Most of the participants are calling attention to ACS because ACS has not placed their children with biological family members.

Fostering Progressive Advocacy members protest on the steps of City Hall in New York, NY on April 16, 2014.

Isaiah Fischer-Collins, 7, with his paternal grandmother, Dianna Collins, Brooklyn, NY on Dec. 21, 2013.

While in prison, D’Juan petitioned the court system and New York’s ACS to place his now 7-year-old son, Isaiah, with his biological grandmother, Dianna Collins. For a variety of reasons, this never came to pass and Isaiah has been stuck in the foster care system for over six years now. D’Juan is drug-free, has a regular job and is looking for new housing. He is granted two hours a week to see his son via supervised visits at Graham Wyndham, a branch of the foster care system. In the meantime, it appears that Isaiah is acting out at school and against authority figures.

In the face of this adversity, D’Juan has launched a campaign (saveisaiah.com) to get his child back. At present, D’Juan has non-custodial parental rights only. If he gets full custody back for himself or the boy’s paternal grandmother, D’Juan feels that at best he can make sure Isaiah does not feel abandoned by his biological family and will have the confidence and emotional security to succeed in life. At the very least, like many disadvantaged fathers with a checkered past, he can teach his son what not to do.

The verdict is due to come in 2015 and it is quite possible that the foster mother will be granted the court’s permission to adopt Isaiah. If the custody goes to the foster mother, in lieu of the recent decision by the Court of Appeals of New York in the Hailey ZZ case, the court lacks the authority to order visitation for the biological family, including the father. D’Juan and his extended family may never see the child again.

D’Juan speaks on the phone to the biological mother of his 7-year-old son in the Bronx, NY on Feb. 11, 2014. D’Juan is appealing to her for help to ensure the foster mother cannot adopt their joint son but the biological mother is on and off drugs which makes her an unreliable source of strength and assistance.

The view from D’Juan’s bedroom in the Bronx, NY on Jan. 24, 2014.

Residents, Buzz, Reed and D’Juan, relax in their 3/4 house in the Bronx, NY on Feb. 1, 2014.

D’Juan Collins’ fragrance “Innocent Black Men” sits on his dresser in the Bronx, NY on Jan. 18, 2014.

D’Juan Collins checks himself in the mirror before heading out of the 3/4 house in the Bronx, NY on Dec. 10, 2013.

D’Juan reaches out to potential customers in Times Square, NY on Jan. 13, 2014. D’Juan has limited job opportunities as a felon and currently sells tickets to make ends meet.

On June 15, 2008, Father’s Day, at the Apostolic Church of God in Chicago, then-Senator Barack Obama delivered a speech addressing a well-known American archetype, the absent black father. His message and tone were accusatory, catering to a public opinion.

In his opening sentences, Obama begins by saying, “…too many fathers also are missing — missing from too many lives and too many homes. They have abandoned their responsibilities, acting like boys instead of men… You and I know how true this is in the African-American community.”

D’Juan represents the legions of “missing” black American men who are caught up in the trappings of intergenerational underachievement as a result of poverty and the effects of the “War On Drugs.” Forty years ago, American inner cities had already begun to feel the impact of globalization and de-industrialization with the loss of jobs matching the skill-sets of inner-city minority men. Today, the minorities living in these areas make up generations of boys and men who have not had access to the education and training to compete in today’s global economy.

80% of our black American men in major cities have criminal records and therefore most are stuck in a cycle of incarceration and recidivism. More African American adults are under correctional control today than were enslaved in 1850. Astonishingly, rates in crime have more or less stayed the course in the US over the past 40 years, but with the changes in sentencing laws, under the auspices of the “War On Drugs,” rates of incarceration have increased by 500%.

D’Juan is part of this statistical nightmare.

D’Juan looks around for potential customers in Times Square, NY on Feb. 10, 2014.

A view of the Bronx from the elevated train in New York, NY on Dec. 14, 2013.

D’Juan Collins, 43, washes his sheets by hand in the bathroom of his 3/4 house in the Bronx, NY on Feb. 1, 2014.

D’Juan uses his laundry bucket to do pull-ups in his 3/4 house in the Bronx, NY on Jan. 18, 2014.

Ellen Edelman of Families, Fathers & Children weighed in about the generational impact of incarceration on the black American family, “When incarceration is a narrative in a family, just as a talent is a narrative where there may be several generations who are musical or good at sports, or with behaviors that are very negative, like drugs or alcohol use, it tends to be a generational narrative.”

Mass incarceration – particularly as a response to drug related crimes – has served to effectively warehouse our black youth and males, pulling them out mainstream American life and separating them from their families. Formerly incarcerated men emerge from prison more ill-equipped to confront the demands of daily life. Minority men, with a very traditional definition of manhood and fatherhood, are particularly emasculated when they have not met the expectations of the husband-father-provider. Reintegration after prison is characterized by the same symptoms of depression, hopelessness and anger that preceded the prison sentence or worse. Maladapted coping skills become the family’s legacy that in turn becomes the community’s legacy and ultimately, as the numbers continue to escalate, America’s legacy.

Studies have shown that without intervention 70% of children with incarcerated parents will follow in their parent’s footsteps and go to prison.

Says Malcolm Davis of The Osborne Association in New York City: “Incarceration creates a ripple effect. When a father goes to prison continuously, the kids see that as the normal and they emulate that, ‘I wanna be just like my dad and Dad goes to prison, Dad comes home, Dad looks good, stays home for a little while, but goes back to prison.’ There is a second side of it where we see the kids without any fatherly guidance in their life so they turn to the streets. They turn to the streets for love, for attention, for support, and the cycle continues.”

D’Juan Collins washes his hands in the soup kitchen before Sunday service at Manhattan Bible Church in New York, NY on Jan. 19, 2014.

D’Juan Collins, 43, sings and prays at the Manhattan Bible Church in New York, NY on Jan. 19, 2014. D’Juan is fighting the New York City foster care system to regain custody of his 7-year-old son, Isaiah.

Nearly six years after now-President Obama’s Father’s Day speech at the Apostolic Church of God, black fathers continue to be amiss in their family’s lives. Young boys continue to take to the streets to seek out the structure, support, and affirmation that is oftentimes lacking in single-parent and foster care households. One can only hope, with the White House’s “My Brother’s Keeper” initiative and Senators Paul Rand and Cory Booker’s bipartisan call for criminal justice reform that family narratives like D’Juan’s will speak of upward mobility among our black American men and boys, freed from the pitfalls of abandonment, poverty, substance abuse and our national response to them, incarceration.

D’Juan and girlfriend Melinda relax in bed in his 3/4 house in the Bronx, NY on April 12, 2014.

BIOGRAPHY

Phyllis B. Dooney is a New York-based photographer and storyteller. After graduating from Pitzer College with a combined degree in Eastern Religion, Art History, and Fine Art, she began her career as a photo art director in the commercial sector. Currently, Phyllis works as a social documentary photographer and her work has appeared in The New York Times, Time Out New York, The Boston Globe, VISTA Magazine, The Huffington Post, and elsewhere online and in print.

Christopher Onstott is a freelance photojournalist, photo editor, and videographer working out of his native Portland, Oregon. Before he turned to image-making, he bounced around in various jobs — most of the sales. He was once high-interest loan officer, pizza delivery boy and used-car salesman. At the age of 24, he took a leap of faith and signed up for a college photo program.

I may have left Portland, but I still have friends there and interviews in the can, so here is Christopher and I talking about PDX, rural Oregon, disaster kits, the grounding effect of portraiture, setting up a business, and specifically setting up a business with your love.

In summer of last year, Christopher went inside Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP) as part of the Oregon Project Dayshoot+30. Our discussion begins there. The two images (above and directly below) are from inside OSP. Other images included are from Christopher’s portfolio.

Q & A

Prison Photography (PP): Tell us about your decision to shoot in Oregon State Penitentiary (OSP).

CO: It was with Oregon Project Dayshoot+30 which was the 30 year anniversary of a day of photographing Oregon by 90 photographers back in 1983. I own the original book One Average Day and the images that stood out to me were the penitentiary photos. In between the usual ‘day in the life’ shots, vineyards, cattle and farmer photos were photographs of a guy in his cell smoking cigarettes.

PP: What was the intrigue?

CO: Prisoners are the under-represented group in Oregon. If you think of Oregonians, you don’t think of prisoners. But they’re residents here.

PP: There’s 14 or 15 thousand people in Oregon’s state prisons these days. Thousands more in county jails.

CO: The Oregon Project Dayshoot+30 was a good reason to get access to OSP which I wouldn’t usually get access to.

I contacted the public liaison office, told them about the project, sent them to the site, sent them a couple of photos of the book that I’d taken on my phone. “Here’s what they did 30 years ago, can I come and shoot?” essentially. They did a security background check and we set up a time. I had only an hour window to shoot. The rest of the day I photographed around Salem.

CO: When I got to the prison, the gentleman I’d been emailing with was not the man I met. The man I’d been in communication with was off work sick. So, immediately there was this disconnect between what I’d asked for and what was being presented to me.

It wasn’t a good experience.

PP: How so?

CO: I wanted to photograph the residents of OSP with a documentary approach, in the vein of the original project. But, my escort’s perception was I wanted take an updated version of the photo from 30-years-ago!

He asked, “So, you want to take this picture?” as he pointed at a print-off of a camera-phone picture of a image in a book! He walked me to a cell, there were two prisoners. He told me I could only photograph one and he gave me 3 minutes. [Laughs]

PP: You had your own art director!

CO: “The image your holding is an example,” I said. “But let’s look at the whole penitentiary.” He said we were not cleared for that, because all the prisoners were about to move for count. There was no flexibility. My escort was accountable to his boss and he didn’t know what had been said before.

PP: What did the subject think about you photographing?

CO: He was totally okay with it. He thought it was cool. I got the impression he knew he was going to be photographed. He was on LWOP (Life Without Parole). Pretty docile.

PP: You think he’s seen the photograph?

CO: I don’t know. I emailed the prison a copy of the photograph in a thank you email.

PP: when you were in OSP, did you cover your tattoos up?

CO: I wore short sleeves. I don’t really think of myself as being tattooed.

PP: Believe me, the prisoners and staff noticed! Do you think there was more to be seen at OSP?

CO: Definitely, just walking in we passed so many people. There was activity and work details everywhere. I was eyeing pictures everywhere but I couldn’t take them. It’s an entire town in there, right? A cultural complex. There’s a million photographs to be made. But I was only to capture a very slim sliver of life.

Still it’s important that there’s at least a representation of prisoners as residents of Oregon 30 years from now.

PP: Shifting gears. You grew up in Oregon.

CO: Grew up in Portland, spent a year in Texas, went to college in Washington State, spent a year in Texas, worked for 4 years at the Spectrum and Daily News in St George, Utah. I couldn’t imagine living anywhere else. The weather sucks five months out of the year.

PP: There’s lots of buzz about Portland, right now.

CO: Oregon really is two different states of mind.

You’ve got the Willamette Valley and the city of Portland and then you’ve got the rest of the state. The one area that doesn’t get attention is Southeastern Oregon. Not a lot of roads, no freeways, hardly a population density. Very rural.

PP: How do you characterize the Portland photo scene?

CO: I think it’s really supportive. We’ve got ASMP Oregon and Newspace. Photographers will move work back and forth and offer one another help. But, on the otherhand, there’s a lot of photographers, so it can be competitive at the same time.

PP: Journalism, editorial?

CO: Magazines. There’s a lot of international attention on the city so we’ve people coming here asking for images. Those stories tend to lean the way of food, style travel; not hardcore news stories. There’s no tornadoes or hurricanes here!

PP: Maybe an earthquake?

CO: I’ve got my 72-hr disaster kit and spare film ready [laughs].

PP: Have you always been a photographer?

CO: No. I’ve been pizza delivery driver. Worked in my dad’s automotive shop. I was a used car sales man for four years. I’ve been a high interest loan officer. I was a bartender for two years. When my father passed away in 2001, I inherited his camera and I was left with “What do I do now?”

My father always told me to be a salesman. But I couldn’t stomach earning a living by getting one over on people. I’d never been to college, so after he died. I decided to go back to college. I was a freshman at 24-years-old! I did Photojournalism at Olympic College in Bremerton, Washington.

I took a picture of a girl’s basketball game and they ran it big in the paper and that was me hooked. [laughs]

PP: What’s easier to sell? Photographs or used cars?

CO: They’re both really hard!

PP: How do you feel about photography. Is it as bad as it’s often made out? Are you a glass half full or a glass half empty thinker.

CO: I think the glass is awesome. The fact you can wake in the morning, pick up a camera and go make a living. I don’t care if your shooting fashion or street photography or using your iPhone, you just have to make pictures. We’re a society that is devouring images.

PP: But a photographer still has to package and shape stories. Can’t just churn them out!?

CO: You still gotta be good. My degree was in visual rhetoric; saying something with an image. Manage that and you’ve accomplished something as a photographer. If you’re a one trick pony, then you’re not gonna last.

PP: I recently met Randy Olson and Melissa Farlow recently.

CO: Randy was my mentor at Missouri Photo Workshop last year.

PP: They’re a couple. There’s a few photo couples out there.

CO: Jenn Ackerman and Tim Gruber.

PP: Two great photographers. Yourself and Leah Nash are a couple. Is there any element of professional competition between you two?

CO: The secret to being in a relationship with another photographer is to be open to criticism and not to take it personally. If you want to grow, take honest feedback from someone who knows you really well and how you operate.

Leah and I edit one another’s work and we don’t take it personally. There’s no relationship argument to be had over photographs.

We’ve agreed not be chasing the same jobs. We’ve formed a separate company, NashCO (Leah Nash & C. Onstott) outside of our own work stylistically that’s focused on corporate and commercial work.

PP: What you working on now?

CO: Street photography. I’m carrying my camera everyday capturing people in moments.

I’ve been working on a personal project of portraits for 5-years now. Using my Hasselblad. It’s slower. Because when I was at the newspaper I was running around photographing people but not really meeting them, you know? I was encountering into people who … I wouldn’t say were marginalized … but they were people who wouldn’t normally be paid attention to by the news. I wanted to slow down.

CO: In news you’re photographing people in the highest points of achievement in their life, or at the lowest points of their life. The big award, the win at the big race, or the battle with cancer. Most of the time, we’re overlooking the median, the mean of existence.

CO: I want to give those everyday people and experiences some attention. In Nevada, New York, Utah, Washington, Oregon, California. Any time I travel, I try to make portraits.

Pick out the person who is trying not to be photographed and ask their name and their story. Often they reply, “Why me?” and my response is “Because you’re interesting.”

I’ve been the only photographer at some of the newspapers I’ve worked at. I was shooting car accidents, house fires and high school sports. My way to decompress from that is to take pictures that I wasn’t taking on the job.

PP: Instagram?

CO: Used to Instagram a lot. When I got my [digital] Leica I stopped posting on Instagram so much. I try to follow people who are making good pictures because I want to be inspired. I don’t want to see pictures of peoples kids.

PP: Where do you shoot?

CO: I’ve been shooting a lot around my neighborhood, the Alberta neighborhood, because it is a gentrified ghetto. There’s a lot of collision. Walk up Alberta or Killingsworth Streets and there’s a photograph every 10 metres. But here’s the hub of Portland’s gentrification.

PP: What else keeps your eye busy?

CO: Portland Squared. It’s a project that Leah started a couple of years ago. 50 photographers. one square mile divided up into fifty squares and you spend the day shooting a square and ASMP event. Last year, they did a bigger square. 2 x 2 miles and 70 photographers. for 24 hours.

PP: Whose work do you admire here in town?

Jason Langer’s work blows my mind. Chris Hornbecker who did the Timbers billboards.

Beth Nakamura’s stuff is awesome; she’s just a kick-ass daily newspaper photographer. Her blog is great too.

PP: Anything else to add?

CO: Don’t move to Portland! There’s too many photographers here! [Laughs]

PP: Ha! Thanks, Christopher.

CO: Thank you, Pete.

SOCIALS

Keep up with Christopher Onstott through his website, Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Follow NashCO on Facebook, Vimeo and web and blog.

EYE ON PDX

Eye On PDX is an ongoing series of profiles of photographers based in Portland, Oregon. See past Eye On PDX profiles here and here.

PREAMBLE: PHOTOGRAPHING FROM WITHIN

One of the most interesting street photographers in America right now is Gabe Angemi. He shoots daily and prolifically. He makes pictures with an iPhone, mostly, but on other cameras too. Angemi is a firefighter in Camden, New Jersey. His profession allows him to get close.

Elevated angles of passing moments in some of Angemi’s photos are reminiscent of images in the many curated Google Street View (GSV) projects. GSV projects tend to divide people. You love them or you hate them. Doug Rickard’s A New American Picture was one of the earliest, one of the best promoted and most divisive of the GSV projects. Why am I mentioning this? Well, Rickard got some flak because he drove-by shot America’s poorest neighbourhoods from behind his computer screen.He didn’t hit the streets himself, but drifted past scenes from the up-high vantage point of a 15-eyed Google car camera rig.

In his look at inequality in America, Rickard *travelled* the streets of Camden. Some of Angemi’s images may look similar but the intent and engagement is vastly different. I’m somehow reassured to know that Angemi is getting down of his rig, chatting with locals, watching the ebb and flow of energies, and shaping the city. He’s also responding to emergencies, securing vacants and putting out fires.

Angemi’s diaristic portrait of the city is raw. But it reflects a place in which 40+% of the population live below the poverty line; a city hall from which three past mayors have been convicted of corruption; a city which can’t support its own schools; and a city in which police misconduct was so rife that law enforcement was placed in the receivership of state forces.

Camden has one of the highest crime rates in the U.S. and is often described as the most violent city in America. In 2012, Camden had 2,566 violent crimes per 100,000 people which is five times the national average. Camden is a rough town, but it is more than its poverty. Angemi consistently puts the hardships and everyday events into a wider context.

Whereas Rickard simply restated that poverty exists in America, and in Camden in particular, Angemi is seeing and sharing it daily. He’s mapping change in Camden and he’s also trying to make it a safer place. That makes him one of the most interesting street photographers in the country.

Angemi pushes his stuff out on a popular but private Instagram account, @ANGE_261.

Scroll down for our Q&A

Q&A

Prison Photography (PP): Are you always using an iPhone? Are you always shooting on the job? Or do you use other cameras and venture out other times?

Gabe Angemi (GA): Not always. But the iPhone is just always there you know? It’s super easy. Occasionally though, it sucks. I also use a 35mm Olympus camera I got from Clint Woodside at Dead Beat Club, and a couple of Polaroid cameras. I’ve been using a Fuji X100 mostly as of late.

Recently, I gave Bruce Gilden and some friends from Magnum a tour of Camden, for a few hours on back-to-back days. I can’t shoot like that; the big cameras and the assistant will never suite me. I love that it’s out there and artists like Bruce are killing it, but I’ll keep making it work with what I got. I suppose that points to why the iPhone works so well for me, it’s just easiest. My photography is more timing, perspective and place than anything else. I suppose I just never had the money to buy a camera that’s *serious*. One day I’ll get a legit one I suppose.

PP: How long have you been a Camden firefighter?

GA: I’ll have been on the job in CMD for 16 years come December. I was recently promoted out of the Rescue Company to Engine Co. 11 in the city’s Cramer Hill section.

PP: How do you take pictures while you’re on call?

GA: I take my job very seriously. Being Johnny on the spot at a fire scene doesn’t jive well with making good photos. I’ve started making photos more and more off duty. The access though — it was invaluable to get me where I could be making interesting photos.

When I was shooting at work years ago, I needed quick and easy so it never interfered with my duty or performance. Hence, the iPhone. Clearly, I can’t have a big ass camera around my neck while I’m fighting fire!

GA: I rarely shoot on the job these days, it is illegal per department policy now. If I take a photo on duty it is with the intent of using it for a training presentation or a PowerPoint.

PP: Because you train other firefighters in fire abatement, right?

GA: Right. And nothing but harmless stuff goes on my social media. Ethical considerations are a big factor. Problems are to be avoided. I had to talk to an attorney about it extensively a few years back.

PP: When did you decide to start shooting in the city?

GA: I started shooting the day I was hired, using an old film camera. Maybe even before that, when I’d stop in a firehouse to see my dad.

Initially, I was just shooting and documenting “us.” Somewhere along the line, I turned the camera towards the city, the issues, the people, the good, the bad. It all seems so normal now but its surely not. Camden’s a fascinating place. I like to be involved in friction, and trying to solve it. I shoot the friction in places that used to be what America was all about, and still is, but for entirely different reasons.

PP: Camden is a tough town. Lots of surveillance, lots of blocks where tensions between citizens and cops are high. How do you and your uniform and your camera fit into that?

GA: I think that collectively, the fire department is looked upon endearingly. The residents have family and friends on the job. The locals know we are not there to break their balls or be indignant. We’re just there to help.

It’s funny how most of the outsiders are the ones who confuse us with the police while were on the street. I mean, I get it, it’s a dark blue uniform, but we are clearly not the police; we do not carry weapons.

Anyone who sees us — from the corner boys to the politicians — should know we don’t judge, assume or push buttons that aggravate anything. We mind our own business, we just want to help.

I’m not dumb though, I’m not always going to fit in, and clearly I’m not going to try to fit me and my camera into a spot that isn’t going to work out. ‘Round pegs, round holes,’ as one of our Deputy Chiefs always said. It carries over from my career to my art.

Tensions are indeed high, and yes, the city is heavily surveilled. The municipality and county had acquired some state of the art detection and monitoring equipment by way of federal grants. The whole city sometimes feels like a prison. Cameras are everywhere, and there’s now a shot detection system that can pinpoint gunfire down to a city block.

GA: Tensions aren’t necessarily a consistent thing, but more like an ebb and flow depending on what’s going on in a particular part of town. Some spots are always hot, others rise and fall. I’m no authority mind you, and I won’t claim to be an aficionado on the vibe on the street between citizens and the law. I pay close attention, but I’m not in any position to really know anything about the police and their plight. It’s not my job. All I really know about them is they have a tough job, and it’s damn dangerous. So is ours.

PP: What’s the reactions of the locals?

GA: My camera gets me smiles, waves, fun poses, friends, conversations and past barriers or preconceived notions. It also gets me dirty looks, threats and projectiles. Obviously, I prefer the former, but just like my job, I take the good with the bad.

PP: What’s your approach?

GA: I ask sometimes to shoot, sometimes I don’t. I build relationships with people I meet on the street when I’m working and try to create a bond or trust so that I can go to their space and photograph them. Sometimes it takes time, other times it can go down right away. Personalities abound; it’s very cool.

PP: Is Camden been talked about, written about, and/or depicted in the right ways?

GA: No.

PP: You’ve a professional experience of the poverty, disrepair, vacancy and the destruction/burning of houses. Can you describe what you’ve witnessed in your work and how you’ve secured and watched properties burn never to be replaced? It seems your job — in real time — has tracked the decline of Camden.

GA: Many of the buildings I was shooting initially for teaching purposes are no longer standing. Anyone that does what I do for any length of time should start to inadvertently become aware of the developing issues and predict whats coming or whats soon to happen. I’ve watched the city disappear over the last 16 years. When you drive around and see vacant lots, you become aware that it was once a thriving community, with street lights and brick and mortar row homes lining the sidewalk. People lived here.

Now, whole stretches of fenced in empty lots do not even have the fences anymore, they have been torn out and cashed in at one of the many local scrap yards. You can hear huge sections of fence being dragged through the street — day or night. The sound of hammers and improvised hacksaws emanate from behind rows of boarded up windows, working to remove any type of metal with a high price per pound. One can often smell gas leaking from stolen basement pipes in vacant buildings, thieves are disinterested in even turning the gas petcock off. Used tires are everywhere, lining the streets like weeds. Plastic bags from the bodegas blow like urban tumbleweeds.

PP: Extreme poverty.

GA: At work, When we are out preplanning vacant row homes, we see needles, used condoms, the insides of ball point pens, lighters, baggies, piles of clothes, stacked mattresses, tinfoil “sculptures,” shit buckets, piles of feces in corners, the carcasses of what would have been a pet in the suburbs … I could go on with this list for a half hour.

We speak to the neighbors, the mail man, the utility provider, squatters, prostitutes, everyone. We just assume the time is coming, you can just sense when a particular spot is going to burn. Then you’d catch the house, or the block, or the building, you turn the corner in the rig at 3am and the street is lit up like your on the surface of the sun.

Its always astonishes me, how it works. Not all of my peers are as tuned in I suppose, or they just prefer to ignore it. That would go for fireman working in any socioeconomically challenged urban city…

But, I think my artistic tendencies and growing up on a skateboard led me to observe closer. I can sorta relate a bit better, growing up in counter-culture mindset. I used to skate, bike, walk or drive around Philadelphia looking at everything from a skateboarding perspective. How could I creatively use the landscape to have fun on my skateboard? Now, I do the exact same thing, but in terms of forcing my way in and out of structures, in terms of understanding who or how many people might be living in a building that is supposed to have no one living in it. I’m constantly training myself to get a better understanding of how poverty affects people out here.

Where are they at? What are they willing to do or endure. I feel that everyone [in precarious or vacant houses] are my responsibility regardless of their job, tax bracket, or societal position. So I pay real fucking close attention and decide what I can and can’t do to make a difference. It’s best to see things up close so you know what you can safely do in the dead of night, maybe half asleep, when you need to be up on your game. We don’t get to warm up. We go full throttle, from a stand still-ice cold position.

The work kills our bodies. We might as well be the buildings were in and out of, becoming more and more structurally unsound over time. I mean fuck, I want to see my girls the next day too, so theres always this friction. I’m not sure exactly how to articulate what I see there, but its fascinating. Its also predictable and above anything else, a travesty. Sitting back is bullshit.

GA: I always say that Camden should have been Philadelphia. A lot of things and people have conspired both consciously and subconsciously over time, both with premeditation and without, to make this place what it is today. There’s so many issues its overwhelming.

I talk to the folks next door or nearby to where we are operating. It’s heartbreaking. Hearing a woman tell me she’s got kids in her house three doors down from where we just put a fire out. They knew it was coming, they saw squatters in and out, they saw addicts using the houses to get high and shelter themselves. They have perpetual anxiety about not if but when [their place might burn down].

There’s a documentary film called Burn, and one of the featured guys in it has a great quote, “I wish my head could forget what my eyes have seen during 30 years of firefighting in Detroit.” That poor bastard has seen some terrible things. I wish I could say I, or any of the guys I work with, were any different. This job can mess your life up, I watched it do it to friends, both mentally and physically. It’s a battle for sanity. We’re getting kicked from all angles, BUT I owe everything I have to the City of Camden Fire Department, and I try to earn that shit every time I go to work, and every time I take, or teach a class. We work hard for what we get, we do a great job, and I’m proud of the work we do.

Camden civilians see more fires than most fire departments.

PP: Fire is a symptom of poverty, right?

GA: I believe so. Our workload is indicative of that. It’s the same in other depressed communities — Detroit; Gary, IN; Flint, MI; Jackson, MS; Stockton, CA; East St. Louis; Bluefield, WV; Baltimore; as well as sections of Philadelphia, Chicago, Oakland, New Orleans. There are so many places dealing with poverty. It would be hard to argue that fire isn’t tied into a cycle of poverty.

PP: What do you colleagues think of your photography?

GA: I’m not really sure! I struggle to keep it separate, and I struggle to combine it. I have a lot of support from guys I spent years of my life with — they support me and it, even if they don’t get it. I’m sure there are guys who don’t know me too well who are not feeling it or very receptive. Some guys have talked to me about it and now understand. All I can do is keep on being me. I’m not looking to hurt, upset, take advantage or manipulate anyone. I want to throw-up when some one says I’m exploiting people. I’m far more invested in this town and its people.

PP: What’s next?

GA: I’d like to make a book, Pete. One of these days, I hope to put together a book dummy.

I would also like to do shooting elsewhere. I’d love to find a grant that would allow me to do what I do in Camden, in other cities. I could go hook up with friends in other fire departments and make photos.

But honestly, I’m trying to adjust to a new role in my job. And be a father to my young daughter. My wife is soon to give birth to a second daughter, so time and energy are harder and harder to come by!

Hopefully next year, I’m going to find myself sitting on the co-op board for Camden FireWorks, a great South Camden artistic endeavor. Those involved hope to start some revitalization on South Broadway out of the old CFD Engine Co. 3 fire house. Heart of Camden acquired it and put a ton of time, energy and grant money into refurbishing it into artist studio spaces, gallery and printing press with a program of lectures and classes.

PP: Anything else you want to add?

GA: I hope that no one ever interprets my opinions, intentions or photography as negative toward Camden. I’m invested here. My father was a CMD fireman for 33 years and busted his ass through two riots and decades of a fire-load that would make most of today’s firefighters quit. I feel that the city looks like it does now by some twisted and fateful design. I give back in my own ways, and try to make Camden a better place.

I can’t get by with out my family, they are the best ever! Thanks Nicole, Maria, Lillian, and Lucia. You allow me to make art, make photos and constantly deal with my obsessive nature and all that comes with it.

I owe a ton more to too many of my friends and influences to write here but they know who they are. ARTNOWNY and the Philadelphia art scene are awesome.

Oh, and firefighters rule! We are here for you.

PP: Cheers, Gabe.

GA: Thank you, Pete.

Today, the Philly Mag published a leaked document about the devastating decline in newspapers. It was created by Interstate General Media, owners of the Philadelphia Inquirer. It showed massive slumps nationwide but particular downturns in the fortunes of Philadelphia’s newspapers.

The slump has been rumbling on for over a decade now but the details in the leaked document make Will Steacy‘s project Deadline even more timely. Steacy is currently raising money to make a photobook and here’s why I think it deserves your support.

DEADLINE, by WILL STEACY

I was once Skyping with an artist on a residency in Europe. During the call, in the background, Will Steacy‘s head popped round the open door. Given the time difference, it was early morning for my friend, and for Steacy.

Pre-coffee, Steacy took the time to say hello. I noticed under Steacy’s arm a stack of the newspapers. Printed news from print newsrooms across the globe. Steacy told me it was his daily ritual to read, for hours, the news stories printed on actual paper. It shouldn’t have seemed so surprising, but in this era of digital information Steacy’s insistence on printed news was, in my mind, unusual. And comforting.

It makes sense that Steacy would not only notice — but also feel attachment — to the dying news daily in his once-hometown of Philadelphia. His photographs document an atrophying Philadelphia Inquirer newsroom. The number of staffers decrease, the presses go silent, the buzz of a breaking news scoop vibrates a little less.

The series is called Deadline, and Steacy is currently crowdfunding on Kickstarter to create a photobook version.

I tweeted last week that Steacy was “photographer, labor guy and workaholic” and deserving of your support. He’s worked on the series for 5 years. His father was an editor with the Philadelphia Inquirer for over 20 years before he was laid off in a round of cutbacks in 2011, and his family has been in the news industry for generations. Steacy talks of the newspaper as a form and as a bastion of an institution holding politicians, corporations and the like accountable to society as a whole. Steacy also believes the decline of the newsroom is a labour issue and more than just profits should dictate the operations of free press outlets.

Under corporate ownership every Inquirer asset is on the table in the strategy to stay alive. Ask any local, and they’ll tell you the Philadelphia Inquirer ain’t what it used to be. The focus on local coverage to secure it’s regional readership hails a goodbye to the days when the Inquirer racked up Pulitzers for fun.

The Philadelphia Inquirer still lives but it’s downsized from 700 to 200 staff, sold and moved out of its iconic headquarters, The Inquirer Building. This move, as documented by Steacy, is arguably one of the best visuals we have to grasp the size of the changes occuring now in news publishing.

While Deadline is specific to the Inquirer, the story is all too common. Large papers such as the Rocky Mountain News have shuttered completely in recent years. This devastating shift in news publishing was reflected in Philly Inquirer’s Hard Years Are Microcosm of Newspapers’ Long Goodbye, an article by my Raw File WIRED colleague Jakob Schiller, last year.

Deadline combines great images, great research, local and national narratives and a personal connection. The Kickstarter rewards are imaginative too: newsroom pencils and pin badges, and a limited edition artwork printed on the same presses that rolled out the Inquirer for decades.

Get over to Kickstarter and fund it!

Kickstarter reward at the $25-level. Poster: “A MIRROR OF GREATNESS, BLURRED” (Edition of 50, hand numbered, signed by artist, 20″ x 24″)

‘Claudia. 4 years’ © Julia Schönstädt

Statement of Being by Julia Schönstädt is a series of portraits and interviews with prisoners in Germany. According to Fotografia Magazine — which is running a series of six portraits currently — Schönstädt’s aim is “to dispel the stigma of the criminal and simply make the subject human.”

Schönstädt has worked with subjects of different age, gender, race and criminal prosecution. Some are sympathetic characters, others less so. Three women in their fifties are addicted to drugs; two see it as a problem, the other not. Harry is only 23 and doesn’t really seem to care if he goes back to prison or not. Then there’s the older guys who seem to be reforming themselves or aging out the game.

Most of the statements are insightful and honest. For example, when asked if prison helps people, Claudia (above) weighs her owns needs against those of others. There was positives for Claudia in the mere fact she was forced to come off drugs, but she accepts without that small mercy, prison is roundly a tough, tough place for most:

I know that I was in a personal situation where prison gave me space to breathe at first. If I would be torn out of my normal life now, and that can happen to anyone, that they get falsely accused, I would probably find that very traumatic. You are very helpless. You have very few possibilities to influence or shape things. You are completely dependent on the good will and concession of the officers. And part of it is also always luck, depending on what kind of people you will be put together with, and the groups that form. I think for a person who isn’t in an emergency situation as I was in, this is very dark.”

In every case, Schönstädt does a good job of revealing the interviewee. I suspect the excerpts are taken from longer conversations allowing Schönstädt to focus on the meat of the message. It’s a well-made project. But I am not without criticisms.

Schönstädt asks “Are You Ready To Listen?” but the query “Are You Ready To Look?” seems as appropriate.

Within in her presentation of both text and image, Schönstädt’s question seems to sideline the importance of the image . (This is not to say that we cannot conceive of a metaphor of “listening” to images, but for the purposes of my argument, I think it’s useful if think of listening as something related to written, read and spoken words.)

The question elevates the words of her subjects. Great. I’m all for portrait sitters having a platform to speak in their own voice. But I get the sense that here photography is used as filler and that the B&W portraits behave as illustration to the words, and as supplement. This is, of course, sad. We know photography can do many things and, I believe, it can be an activating agent in a project. In a purported photography project such as Statement of Being it absolutely must be activating.

But are we ready to look? When I do and inspect Schönstädt’s portraits I’m left wanting. They’re flat.

‘Volkert, 13 years’ © Julia Schönstädt

Now, we all know how difficult it is to make a good portrait, but these are so tightly cropped and made monochrome, I feel like I’m looking at a really earnest effort by an artist to depict someone, as opposed to looking at that someone. Schönstädt’s politics are aligned with mine and her use of multiple media is praiseworthy, but I don’t feel she has managed to do what great photography does, which is to get out the way of itself. Proximity doesn’t always mean intimacy.

I wonder if Schönstädt made the decision to get close so that she could remove evidence of the prison environment from her pictures? To give her subjects best chance at presenting as a person first and not as a criminal as default? I understand the urge but it’s not necessarily a solution. Nor is it necessarily a problem. For example, Robert Gumpert has used B&W imagery but drawn back and made the most of sterile pods in the San Francisco jail system to make compelling portraits. In short, I’d like to see more variation in Schönstädt’s portraiture.

‘Oliver, Life Sentence’ © Julia Schönstädt

I’m currently writing an essay “How To Photographs Prisoners Without Shaming Them.’ Most of the essay focuses on pairing photography with other media. In some bodies of prison portraiture it is either stated or obvious that the photographer collaborated with the subject over the composition and presentation. Given that Schönstädt’s portraits are identical in direction, I wonder if this was the case?

I am not saying Schönstädt doesn’t respect her subjects the opposite is clearly the case, but photography is more about the viewer than the practitioner and we must always be aware of existing stereotypes and prejudices when making photographs. The audiences’ reaction trumps the author’s intent. The audience’s reception is what defines a work ultimately.

Take the above image of Oliver as an example. Some might read his face as mischievous. Others, no doubt, will read it as menacing and devilish. I don’t think the appearance of a sinister looking male helps win sympathy. This is tragic for a project which is wholly sympathetic to the prison population.

Oliver speaks frankly and sensibly:

I became violent very early on. First there were money-related crimes starting at 7 or 8 years old. Violence came a bit later, but when I was 7 or 8 years old I stole and so on. Unfortunately, it wasn’t until I was 22 that I was held responsible for the first time.

It really struck me that something wasn’t right with me or with my story when a great deal of my family passed away – my grandfather, grandmother, and father [after being imprisoned]. I was married then and my wife divorced me. She stayed with me for 5 years but then she got to a point where she couldn’t take it anymore. And all that lead me to think something isn’t quite right here. Then I went to see a psychiatrist and got even more reasons to think about everything.

I had relatively little empathy for people, that’s just the way I grew up. I was raised in a violent environment. But that doesn’t mean that I was consciously punished by being beaten, more in a way you would also train a pitbull. […] I didn’t feel like that was something that wasn’t okay. I experienced my childhood as something really nice. Only through a person from the outside, I realised that it wasn’t all that normal, the way I grew up. And through realising that, I was able to reflect much better.

Oliver is in full grasp of his antisocial behaviour and has made steps in therapy to address it. He’s locked down for life but trying to improve himself. He is not devilish. How do I know this? Again because of Schönstädt’s keen efforts. Listen to Oliver speak in the video below and ask if the mood and personality of his still portrait tallies with that of the video portrait. Are we ready to look?