You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Documentary’ category.

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

A WITNESS TO “HELL”

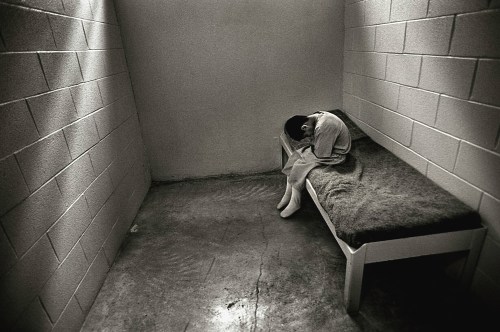

“Prisons are the stuff of fantasy, but there’s nothing spectacular about the reality I experienced there,” writes French photographer Grégoire Korganow in the artist notes for his current show Prisons: 2011 – 2014 at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) from Feb 4th-May 4th, 2015.

“What really turns the ordinary into a nightmare and creates the hell of incarceration,” he continues, “are the multiple and repeated acts of degrading treatment — demeaning rules, solitude, promiscuity, insalubrity, idleness, absence of prospect, discomfort.”

According to Korganow, a suicide attempt is made every three days in French prisons.

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

Parloir, 2012. © Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL.

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO BECAME PRISON INSPECTOR

MEP is presenting 100 of Korganow’s photographs for the first time. He began making photographs in French prisons in 2010 during the filming for the documentary film by Stéphane Mercurio, In the Shadow of the Republic which describes the work of Jean Marie Delarue, The Comptroller General of Places of Deprivation of Liberty (CGPL).

When filming wrapped up, Delarue asked Korganow, if he’d his team and make a document and inventory of contemporary French prisons. It was an unprecedented, unorthodox and remarkable opportunity. Between January 2011 to January 2014, Korganow photographed twenty prisons — remaining in each for between five and ten days.

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

“I penetrated to the heart of incarceration in France,” says Korganow. “I could photograph everything, inside the cells, the exercise yard, visiting rooms, showers, a solitary confinement … day or night. No place was forbidden.”

Delarue and Korganow had an agreement. Any and all of Korganow’s images could be used to illustrate CGPL reports. Then, at the end of Delarue’s term in May 2014, Korganow was free to publish the work under his own editorial.

“This is a first in France,” says Korganow. “Never before has a photographer moved so freely in prisons.”

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

TENTATIVE FIRST FOOTSTEPS INSIDE

Korganow admits to apprehension in the beginning.

“I wondered how those detained would welcome me. I too had a caricature of the prison and was afraid of not being able to return in connection with them.” Korganow wrote for Vice. “My relationship with detainees were frank. I spent a lot of time listening to them because the prison is a place that suffers from a lack of listening. I did not judge or ask them what they had done. I was benevolent, sometimes even when some inmates were unsympathetic to me. Fights between detainees are common. They start with a pair of coveted sneakers, a debt of cigarettes or a dirty look. I noticed that they were often brief, silent and extremely brutal.”

“It’s this closeness of confinement I’m trying to capture in colour, up close and personal, with no effects,” explains Korganow to MEP. As best he can Korganow avoids focusing on faces and individuality. He doesn’t want viewers to get stuck on speculations of who and what the prisoners are and did. Instead he tries to unleash an emotive narrative that describes the oppression of the place.

“I use little touches, soak up the geography of the prison, the light, sounds, smells and stories of the inmates. I capture the inexpressible, time standing still, life shrinking, fading,” he says. I offer the possibility to feel [the prison].”

Baumettes Jail in Marseille was the worst Korganow encountered — deplorable dirt, odor, noise or “Hell!” as he describes it. The photos were later published in the French outlet under the title ‘Prison of Shame’.

WITHIN A TRADITION OF FRENCH PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

Korganow has made the most of his phenomenal access producing an unrivaled and varied of body of work about the French prisons. Nothing as engaging has emerged since Mohamed Bourouissa’s Temps Mort, Mathieu Pernot, Les Hurleurs, and (going way back) Jean Gaumy’s Les Incarcérés.

TimeOut Paris feels Korganow’s study deserves a place alongside the great social documentary of the medium — beside Lewis Hine’s factories, Charles Nègre’s asylums and Jacob Riis’s slums.

“It’s a hard-hitting show, but without drama or ‘miserabilism’,” writes TimeOut.

It’s a bleak picture for sure. Pay attention to any individual aspect of the work and you’ll be rewarded. The color of his images is dirty. In an effective way. Does that make sense? To me, the work, the scene and the entire enterprise feels tainted.

True colors fall away and dissipate under the weight of the hardware, walls and grills they coat. Everything is tinged, chipped damaged. Colour plays second fiddle to line. Form and line themselves describe constant claustrophobia.

Ronde de nuit, 2010. © Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL.

Salle d’attente, 2012. © Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

Subtly, at first, and then over time building to a cacophony is Korganow’s use of windows, apertures and grates. His near anonymous subjects peer out and through portholes. In many cases, this use of inside/outside metaphor and a yearning for the great beyond comes across as trite but not in Korganow’s Prisons. He succeeds in his aim to describe the foreign, oft-fantasied world of prisons. He presents a world defined by its fabric and that fabric assumes it’s own operative force. Korganow recalls meeting a 36 year old prisoner. He’d been locked away aged 19, on an original sentence of 3-years.

“He had accumulated an incredible amount of penalties for offenses committed within the prison abuse, violence, arson, etc,“ wrote for Vice. “He who refuses to submit to the authority of the prison administration will probably never be released. He is buried alive.”

When the not so young man spoke to Korganow, his release date was 2040.

—

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

Distribution des cantines, 2010. © Grégoire korganow pour le CGLPL.

© Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

—

BOOK

The book Prisons – 67065, by Grégoire Korganow, is published by Neus Les Belles Lettres. The “67065” in the title refers to the number of prisoners in the French system at the time of publication.

—

BIOGRAPHY

Grégoire Korganow graduated in Applied Arts from the Ecole Estienne, Paris. Following his studies, in 1991, he documented change in the former Soviet bloc. His photographs of the 1993 riots in Goutte d’Or, Paris, propelled him into the press limelight. Korganow makes images “as an invitation to look at the flaws, paradoxes, contemporary disorders. He is interested in off-screen, with the remote. The body, stigma, and social transformations are central in his work.” He has photographed housing crises (1994), undocumented persons (1995), the Mapuche Indians of Chile (2003), Iraqi victims of war (2010) and alcoholics (2011) .

Korganow’s practice spans photo, film band broadcast media, as well as criticism of those same forms. IN 2001, he was co-founder of Air Photo magazine. He was a creative director of the Being 20, the Alternative photobook collection. He’s worked with directors Stéphane Mercurio and Christophe Otzenberger. Also, attracted by the off-screen, he’s photographed the 2002 French presidential election, production stills for movie production, and fashion shows

In 2008, his series Wings and Next about the lives of families of detainees, showed at Rencontres d’Arles. Between 2011 and 2014, as Controller of Places of Deprivation of Liberty, he made a long form survey of confinement in France titled Prisons.

Korganow’s work has been published in L’Express, Télérama, Marie Claire, Geo, National Geographic, and The New York Times. He was a member of the Métis Agency (1998-2002) and is now a member of Rapho (2002-).

—

Cour de promenade, 2010. © Grégoire Korganow pour le CGLpL

—

Site Unseen: Incarceration flyer. Featuring the work of Jack L. Morris, a California prisoner who has been in solitary confinement for almost 25 years.

Do artworks made on opposite sides of prison walls work together in a gallery space?

Yesterday, at the Los Angeles Valley College, in Valley Glen, CA the exhibition Site Unseen: Incarceration came down form the walls. It was an exhibition bringing together prisoner-made art with artworks made by outside artists about prisons. (Catalogue in PDF, here)

Some artists I knew — Alyse Emdur, Anthony Friedkin, Los Angeles Poverty Department, Sheila Pinkel, Richard Ross, Mark Strandquist, and Margaret Stratton. Others are new to me — Robert V. Montenegro, Jack L. Morris, Brendan Murdock, Gabriel Ramirez, Gabriel Reyes, Robert Stockton and David Earl Williams.

Shamefully, all those names with which I am unfamiliar I quickly learnt are prisoners. Why shame? Well, it’s all about consistency. I value activism that is built upon close alliance with, and information, from prisoners. There are no better experts on the system than those subject to it. At the very least, I should know and support the leading Prison Artists.

However, when it comes to painting and illustration, I have adopted lazy double standards. Without examination, I have demoted prisoner made art — commonly referred to by the catch all “Prison Art” — to an inferior status. I have prejudged most Prison Art. For my own comfort, I have bracketed Prison Art as naive and limited. I’ve conveniently focused on scarcity of supplies inside prison of prison to cursorily explain the lo-fi aesthetic of Prison Art.

My “logic” blinded me to the invention, resourcefulness and resistance inherent to almost all prison art. Hell, we’ve got prisoners making work out of M&Ms.

Site Unseen: Incarceration, therefore, is a nice kick back in the right direction. If we don’t have prisoners’ own artwork upon which to meditate then we lose site of the issues fast. As much as I have championed the work of Emdur, Ross, Strandquist and the Los Angeles Poverty Department, I want to now celebrate the works of Jack L. Morris, Brendan Murdock, Gabriel Ramirez, Gabriel Reyes and David Earl Williams.

I wish also to applaud Sheila Pinkel for bringing together inside and outside, and for committing the oppressed and their allies to one another upon gallery walls.

Sheila Pinkel. Site Unseen: U.S. Incarceration (2014). 7’ x 14’ Archival ink jet prints. Pinkel remarks, “Site Unseen: U.S. Incarceration includes the major laws that have resulted in the expansion of the prison system, the Sentencing Reform Act (1984), Mandatory Minimum Sentencing Law (1986) and Three Strikes Law (1994). It is important to note that in the 1960s, during the civil rights era, rate of incarceration was declining as people adopted the ‘rehabilitation not incarceration’ attitude. However, after the Rockefeller Drug Laws took hold, incarceration in the United States began to grow exponentially. Also included is demographic information about the high rate of incarceration of non-white people and women, the great number of people being held in solitary confinement and the massive amounts of money being made by investors in the prison industrial complex. The backdrop for the graph is a set of images from U.S. history taken in the 19th and 20th centuries that reflect the treatment of minorities and prisoners. The poor, non-white and uneducated make up the majority of incarcerated today.

Origins of the Show

In 2004, Pinkel exhibited for the first time her mammoth work Site Unseen: U.S. Incarceration (above). While the shared title between this catalyst work and the exhibition confuses matters a little, it demonstrates the degree to which Pinkel is bound to prison reform. Passion + politics is usually a good recipe for art.

Pinkel’s motivations for mounting the show are many — concerns for Mumia Abu-Jamal’s case; an awareness of slavery (past and present); the doctrines of ownership and manifest destiny; sensitivity to the quiet traditions of aboriginal people; a raised consciousness toward the unparalleled use of torturous solitary confinement; and the profit making industries of the prison industrial complex; and more besides.

The urgent issues within the reform and abolitionist movements are so great that often they can drown each other out, or obscure one another. Perhaps, that is where silent 2D artworks come to play their part. Perhaps, a gallery space in which viewers can mediate their own responses is a hushed but vital contribution to the reform debate?

David Earl Williams. Parrots (1996). 22” x 28” Ball point pen.

It is helpful for me to interrogate the idea that gallery shows and art have an effect upon political realities. I make a conscious effort to justify my workand others’ and to continually ask if analysing images and creative output from prisons changes the daily experience of the United States’ 2.3 million prisoners.

I conclude, often, that conscientious and intellectually honest analysis of images from prisons plays its role in the wider discussion needed to drag us out of this prison crisis.

Prison Sketches in the Absence of Prison Photos

Undoubtedly, in the past few years, solitary confinement has emerged as one of the main, digestible and terrifying issues behind which reformers could win arguments, gain traction and mindshare. The public now know that 80,000 people on any given day are subject to psychological torture within our prisons.

Many of the photographs of Supermax and solitary units — and there are not many — have come about because of court ordered entry to facilities. With the exception of Social Practice make-believe, artists and photographers have, for the most part, failed to image these dark, hidden spaces for the public. I’m apportioning no blame here, just pointing out fact. With that understanding, then, it is significant that the majority of prison artists in Site Unseen are either in solitary or on death row.

Brendan Murdock. Tower (2012). 9” x 12” Linoleum cut print.

One of the artists in Site Unseen is Jack L. Morris, a creative spirit with whom Pinkel has had a lasting personal and professional relationship. In 2011, Pinkel began corresponding with Morris. At that point, he’d been incarcerated for 31 years. In 1978, aged 18, Morris was sentenced to a 15 years to life for being an accomplice to a murder. When the California Department of Corrections (CDCr) opened Pelican Bay Sate Prison (the first state-run Supermax in the nation) in 1989, Morris was transferred. He’s been in solitary confinement since.

“During this time he has not seen sunlight or touched another person,” says Pinkel.

Jack L. Morris. Turtle (2012). Dimensions: 12” x 12” Medium: pen, pencil, peanut butter oil, pastel color.

Pinkel points out that the decision-making power to place someone in solitary is solely in the hands of the correctional officers. Checks and balances against abuse in this ‘Us vs. Them’ equation are largely absent. Pinkel believes that Morris, like many prisoners in the SHU, is subject to a Kafkaesque situation in which solitary is inescapable. While policies are shifting after attention from Sacramento politicians, it remains incredibly difficult to get out of the SHU if CDCr has classed you as a gang member.

“Jack has not been involved in gang activity and has had no ability to be involved in it since he has been in solitary. However, he is repeatedly denied release from solitary and has had his designation increased to active gang affiliation,” says Pinkel. “At the moment, there is no legal way for him to get out and, to my mind, there is no good being served by his continued incarceration, either in solitary or in prison at all.”

Alyse Emdur. Anonymous backdrop painted in New York State Correctional Facility Woodburn (2012). Dimensions:42” x 52” Inkjet print.

Clearly, Pinkel has an affiliation. Put that aside though and consider Morris for his work and you can’t help but be impressed. In order to prevent himself “losing his mind”, Morris created poems, drawing and letters. Pinkel published them in the book The World of Jack L. Morris: From the SHU.

“Together,” says Pinkel, “they form a complex picture of a talented person who believed most of his life that he was not intelligent.”

And so we arrive here. At Morris’ and other art from inside. To be mesmerised by the intricacy of the work is understandable, but more-so we should be quietly and slowly scrutinising the work and using it as a gateway to a psychology we must surely hope we, or any of our loved ones, ever come to know.

Prison illustrations work very similarly to photographs in some ways, in that tropes recur and we find ourselves glossing over them. We presume that the system gives rise to them same type of images of flora, fauna, cars, tattoo-inspired designs, versions of women, motorcycles, sad clowns, tears and blood. These things are prevalent, but individual touches exist in the gaps and it is there we may identify the individual artist.

Gabriel Ramirez. De Profundis … Dreams (Before 2007). 11.5” x 15” Medium: Pencil on manilla envelope.

The worst thing prison art and photography, alike, can be is misunderstood as aesthetic cliche and used as excuse to bypass the social conditions from which they arise. Prisoner art from solitary is the most reliable source of imagery on which we can rely to learn about extreme confinement. We just need to give it space to percolate. A gallery can do that.

There’s a perverse clash of time appreciation at work in order for prison art to have an effect. The artist labors for days and weeks on a single piece and goes to great lengths to deliver it outside the institution. On the outside, we’re spoilt for images and it’s almost luck or strange happenstance for us to spend more than a few seconds with an image. But, it is possible and a gallery can do that.

Mark Strandquist. Windows From Prison (2014). Banners 5’ x 11’. Digital prints on vinyl.

Strange Brew

As might evident, I am largely in support of Site Unseen. However, looking over the catalogue, I am a bit skeptical toward the mix of works. Does Mark Strandquist’s work (above) that relies heavily on public education and engagement work when he cannot transform the gallery into a workshop space or collaborate with local reform groups? Are we getting to the point that a prison show cannot exist without the work of Richard Ross!? (I’m friends with Richard and had breakfast with him this morning; he won’t mind the snark). It just seems Ross might be an easy option.

Is Site Unseen a prison art show supported by outside sympathisers, some of whom happen to be artists? Or is it a genuine attempt to level the field and present artists inside and outside as equivalents? The latter is a tough proposition. I have seen it done though. The Cell and the Sanctuary (Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History) managed to knit insider and outsider artists works together, but they managed it effectively because they were all either students or faculty in the William James Association’s Arts In Corrections program at San Quentin. A visual thread ran through The Cell and the Sanctuary that is not as immediately apparent in Site Unseen.

Margaret Stratton. Ship’s Passenger Log, December 1916, Ellis Island, New York City, June 29, 1999, 10:35 a.m. (1999). 16” x 20”. Archival digital print.

The main culprit, for me, is the work of Margaret Stratton (above). I’ve constantly wondered what use have images of decaying/ abandoned prisons for connecting us to pressing contemporary prison issues. I can find value in most other works in Site Unseen as they’ve a clear umbilical cord to the tumorous, pulsing Prison Industrial Complex. We can sense the toxic bile of the system in the majority of the works. We can wonder at the ability to stay sane and creative from within such a system. I get none of that awe from Stratton’s work.

I understand Stratton’s B&W images employ a different route to the issue and I don’t want to suggest there’s any inherent flaw in the work or its tactics. The fault, if any, lies with the decision to include this type of work that I identify as an outlier within the collected works.

Four Convicts, Folsom Prison, CA (1991). Dimensions: 11” x 14” Black and white gelatin silver print.

Another , but slightly less obvious, outlier is Anthony Friedkin’s photo of four Folsom prisoners in the early 90s. It is a captivating portrait for sure (one that I featured very early on Prison Photography) but it is hardly representative — of either recent photographs from prisons, or the U.S. prison population as a whole. Friedkin is best known for his illuminating access into, and photographs of, gay culture in San Francisco and Los Angeles. His respectful treatment of these derided communities was light years ahead of mainstream political consciousness. Friedkin lived among the LGBQT community and the intimacy and support shows through in his work.

I cannot think that Friedkin had a mere fraction of that sort of access to the prison population. I suspect he made his image above on a single visit to Folsom Prison. I have not seen any other photographs from prison by Friedkin. And so, this image, is neither representative of Friedkin’s work. It is ham, distant and reliant on the tropes of prison cliche. Not only is it out of place, it is out of time.

Gabriel Reyes. Like a Hook (Before 2007). 8.5” x 11”, Ball point pen on paper.

As far as I am concerned, any and all mentions of Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscapes and the Los Angeles Poverty Department’s performances (below) are absolutely essential and cannot be reiterated enough. Each are powerful statements on the nature of power and the over-reach of state control.

LAPD’s dramatisations are informed by the experiences of people who have been incarcerated and Emdur’s collected portraits and large format photos of prison visiting room backdrops originate from a keen engagements with the visual logic of carceral systems.

Robert Stockton. Fight (Before 2007): 8.5” x 11”. Pen, additional color.

Prisons and criminal justice reform are gaining attention in the news and public consciousness (a good thing), but just because the conversation is being had and the appetite for a show like Site Unseen might be more ready, the challenging logistics of putting together a curated show of this kind remain unchanged. Kudos to Pinkel for bringing togther artists from inside and outside prison invested in the same goal of making the U.S. a less dangerous, punitive and misunderstood place.

At first glance, the mix of ‘prison art’ on one hand and ‘art made about prisons’ on the other might appear incongruous, but that attitude is exposed as flawed very quickly. As the majority of works in Site Unseen emerge as responses to this country’s brutal, class-dividing prison system, I must conclude that they can do nothing but work together. And so must we if we’re to scale back on decades of fear, bad law and failed policy. If you need resolve and fire-in-your-belly for the task then merely look to the work of those who are subject to confinement. You’ll find it, quietly roaring, there.

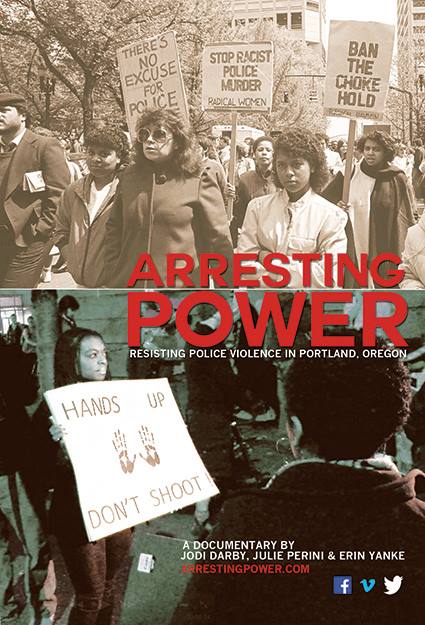

ARRESTING POWER

Portland’s a pretty small town. When I lived their I was a fellow panelist with Julie Perini. Jodi Darby once beat me, by mere seconds, to a killer secondhand sweater in a donation pile on the street. I’ve never met Erin Yanke. The three producers have recently completed Arresting Power, a documentary about resistance to police violence in Portland, Oregon.

I supported the Kickstarter to get the film over the finishing line, so I am happy to see it out in the world. On Friday, May 8th, Arresting Power will screen at the Kala Art Institute in Berkeley, CA.

Arresting Power – Resisting Police Violence in Portland, Oregon provides a historical and political analysis of the role of the police in contemporary society and the history of policing in the United States. It provides a framework for understanding the systems of social control in Portland with its history of exclusion laws, racial profiling, gentrification practices and policing along lines of race and class. It serves to uncover Portland’s unique history of police relations and community response.

Arresting Power features interviews with the families of people who were killed by Portland police, victims of police misconduct, local historians and community organizers. Utilizing archival newsreel from the Oregon Historical Society’s moving image archive, the film explores the history of police reform and abolition movements that have been active throughout the past 50 years.

Watch the trailer here.

——–

Friday, May 8, 7pm

Kala Art Institute

2990 San Pablo Avenue, Berkeley, CA

Sliding scale $5 – $15

Refreshments will be served

Screening followed by Q&A with the filmmakers

American photographer Willow Paule has spent half her time, in recent years, in Indonesia. She recounts in PsychoCulturalCinema how she slowly learnt about the past incarcerations of her two friends. Their conversations together led to more questions. Paule writes:

Through my research and conversations with these former prisoners in Indonesia, I discovered that they had faced rampant corruption, extortion, and violence in prison. I found that people were often convicted without solid evidence, that they sometimes possessed only small amounts of narcotics or marijuana but were given long drug distribution sentences, while large time dealers got off with lighter sentences. The person with the fattest wallet got the best treatment.

I learned that mentally ill people often became police targets, and periodically drugs were planted on them in order for police to meet arrest quotas. Once they were locked up, they didn’t necessarily receive adequate care, and they sometimes created turmoil in the cramped cells they shared with the general population. Many people told me disheartening stories about human rights abuses in Indonesian prisons.

My focus is the U.S. prison system, but as I say, dryly and reductively, on my bio page, “problems exist in other countries too.” Paule knows this all too well. She recorded the art that her two friends created as a matter of survival and also their difficult reentry into society. There, as here, jobs are difficult to come by for former prisoners and the stigma of prison lingers long.

The extent to my knowledge on the Indonesian prison system spans the length of Paule’s article. The system sounds dire.

“Prison sentence lengths were decided depending on bribe amounts and prisoners had to pay for a cell or face daily beatings and electrocution in solitary confinement,” writes Paule.

Connecting Paule’s years-old inquiry to today, in the U.S., is Paule’s desire to repeat the methodology and record the stories of returning citizens in America.

There’s no shortage of people in this country with whom Paule could meaningfully connect and weave their history and story over a long period as she did in Indonesia. It takes more than just images though; I encourage Paule and all young photographers to use audio, family archives, collaborative processes and — as Paule did here — a focus on non-photo 2D artworks. Most of all, I encourage young photographers to empower not only individuals impacted by incarceration through the telling of their stories but also to empower small local communities by exhibiting and programming the work with those most closely implicated in the issue.

Simply put, a show at the local community centre is as important as one in the brand name gallery downtown. The former deals in hearts and minds, the latter in sales.

A church choir sings during a sparsely attended Sunday mass in Shushi. Shushi was primarily an Azeri city of cultural significance. Once home to 30,000 people, only 3,000 people call it home now.

My article When a Country Is Not a Country about Narayan Mahon’s series Lands In Limbo just went up on Vantage, for Medium.

Mahon travelled to Abkhazia, Northern Cyprus, Transnistria, Nagorno Karabakh, and Somaliland — five nations that are not formally recognised by the international community as states.

Lands In Limbo defies genre. It is partly documentation, but not complete documentary. Some of the images look like news photos but Mahon has a stated artistic intent. Here is an inquiry about huge geopolitical forces in a globalized 21st century … but it is based upon momentary street photos and portraits.

“I wanted to see what these countries’ national identities looked like, [learn] what’s it’s like to live in such an isolated place,” says Mahon.

Read the full article and see Mahon’s image large at Vantage.

Friends enjoy an afternoon on the Black Sea coast of Abkhazia. Much of the Abkhaz coastline is littered with rusting ships and scrap metal.

An Abkhaz man, known as “Maradona,” yells obscenities about Georgian politicians and declares the freedom of Abkhazia.

A man walks into a small store in the center of Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno Karabakh. Stepanakert lost nearly half it’s population to forced deportation of Azeris during the breakaway war.

A man stands among snow covered pig heads in Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno Karabakh.

Karabakhi soldiers stand guard at a war memorial in Kharamort, a village that was once evenly populated by ethnic Azeris and Armenians. The village is now half the size since the Azeris fled and their homes were burned.

During and after the breakaway war with Azerbaijan, Karabakhi-Armenians burned and destroyed not only Azeri villages and town quarters but also desecrated Azeri muslim mosques and cemeteries. This is common practice throughout the Caucasus, used as a deterrence for people wanting to return to their homes.

Men and women walk through the bustling central market in Hargeisa, passing war-damaged buildings.

Shabxan, a young Somali girl living in rural Somaliland, does chores in the home.

A young Somali boy checks himself out and fixes his hair in the mirrors of a small barbershop in Hargeisa.

TEACHING PHOTOGRAPHY INSIDE

I’ve known about Vance Jacobs work in a Medellin Prison for as long as it has been in published form, but this recent post by StoryBench reminded me of the excellent and brief video reflection Jacobs gives about his time teaching prisoners to use cameras to document their own lives. Originally, Jacobs was going to be the only person photographing, but at the eleventh hour the sponsoring NGO for thre project changed the concept and he was asked to educate a dozen men in prison.

“You could tell it had been a long time since the prisoners in my class had received this much attention. But I also had high expectations and those expectations led to it being a very important experience. They started taking a tremendous amount of pride in their work and they started to understand that criticism could be a really important part of their work and theta they could grow from it,” says Jacobs.

This type of introspection and self-documentation is vital, in my opinion.

At the final exhibit inside the prison of 35 images, 5 went missing. “To have a photo stolen was a badge of honor,” says Jacobs. “It meant someone thought they were worth stealing.”

BIO

Vance Jacobs, a San Francisco-based photojournalist and filmmaker whose work has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic Books and Esquire magazine. He talks about his creative process and behind the scenes details of his different shoots at his ‘Behind the Lens’ YouTube channel. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

See features on Jacobs’ work at GOOD, WonderfulMachine, Photographer on Photography and PDN Online.

10, 11, 12, 13 & 14. © Steve Davis.

TRY YOUTH AS YOUTH

Currently on show at David Weinberg Photography in Chicago is Try Youth As Youth (Feb 13th — May 9th), an exhibition of photographs and video that bear witness to children locked in American prisons. As the title would suggest, the exhibition has a stated political position — that no person under the aged of 18 should be tried as an adult in a U.S. court of law.

In the summer of 2014, selling works ceased to be David Weinberg Photography’s primary function. The gallery formally changed its mission and committed to shedding light on social justice.

Try Youth As Youth, curated by Meg Noe, was conceived of and put together in partnership with the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. Here’s art in a gallery not only reflecting society back at itself, but trying to shift its debate.

The issue is urgent. In the catalogue essay Using Science and Art to Reclaim Childhood in the Justice System, Diane Geraghty Professor of Law at Loyola University, Chicago notes:

Every state continues to permit youth under the age of 18 to be transferred to adult court for trial and sentencing. As a result, approximately 200,000 children annually are legally stripped of their childhood and assumed to be fully functional adults in the criminal justice system.

This has not always been the case in the U.S. It is only changes to law in the past few decades that have resulted in children facing abnormally long custodial sentences, Life Without Parole sentences and even (in some states) the death penalty. In the face of such dark forces, what else is art doing if it is not speaking truth to power and challenging systems that undermine democracy and our social contract?

Noe invited me to write some words for the Try Youth As Youth catalogue. Given Weinberg’s enlightened modus operandi, I was eager to contribute. Here, republished in full is that essay. It’s populated with installation shots, photographs by Steve Davis, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, and video-stills by Tirtza Even.

–

Scroll down for essay.

–

Image: Steve Liss. A young boy held and handcuffed in a juvenile detention facility, Laredo, Texas.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Image: Steve Liss. Paperwork for one boy awaiting a court appearance. How many of our young “criminals” are really children in distress? Three-quarters of children detained in the United States are being held for nonviolent offenses. And for many young people today, family relationships that once nurtured a smooth process of socialization are frequently tenuous and sometimes non-existent.

–

Try Youth As Youth Catalogue Essay

–

WHAT AM I DOING HERE?

–

Isolated in a cell, a child might wonder, “What am I doing here?” It is an immediate, obvious and crucial question and, yet, satisfactory answers are hard to come by. The causes of America’s perverse addiction to incarceration are complex. Let’s just say, for now, that the inequities, poverty, fears and class divisions that give rise to America’s thirst for imprisonment have existed in society longer than any child has. And, let’s just say, for now, that the complex web of factors contributing to a child’s imprisonment are larger than most children could be expected to understand on a first go around.

As understandable as it might be children in crisis to ask “What am I doing here?” it should not be expected. Instead, it is we, as adults, who should be expected to face the question. We should rephrase it and ask it of ourselves, and of society. What are WE doing here? What are we doing as voters in a society that locks up an estimated 65,000 children on any given night? In the face of decades of gross criminal justice policy and practice, what are we doing here, within these gallery walls, looking at pictures?

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility, Albany, Oregon, by Richard Ross. “I’m from Portland. I’ve only been here 17 days. I’m in isolation. I’ve been in ICU for four days. I get out in one more day. During the day you’re not allowed to lay down. If they see you laying down, they take away your mattress. I’m in isolation ‘cause I got in a fight. I hit the staff while they were trying to break it up. They think I’m intimidating. I can’t go out into the day room; I have to stay in the cell. They release me for a shower. I’ve been here three times. I have a daughter, so I’m stressed. She’s six months old. At 12 I was caught stealing at Wal-Mart with my brother and sister. My sister ran away from home with a white dude. She was smoking weed, alcohol. When my sister left I was sort of alone…then my mother left with a new boyfriend, so my aunt had custody. She’s 34. My aunt smoked weed, snorts powder, does pills, lots of prescription stuff. I got sexual with a five-year-older boy, so I started running away. So I was basically grown when I was about 14. But I wasn’t doing meth. Then I stopped going to school and dropped out after 8th grade. Then I was in a parenting program for young mothers…then I left that, so they said I was endangering my baby. The people in the program were scared of me. I don’t know what to think. I was selling meth, crack, and powder when I was 15. I was Measure 11. I was with some other girls — they blamed the crime on me, and I took the charges because I was the youngest. They beat up this girl and stole from her, but I didn’t do it. But they charged me with assault and robbery too. This was my first heavy charge.” — K.Y., age 19.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

I have spent a good portion of the past six-and-a-half years trying to figure out just what it is that images of prisons and prisoners actually do. Who is their audience and what are their effects? If I thought answers were always to be couched in the language of social justice I was soon put right by Steve Davis during an interview in the autumn of 2008.

“People respond to these portraits for their own reasons,” said Davis. “A lot of the reasons have nothing to do with prisons or justice. Some people like pictures of handsome young boys — they like to see beautiful people, or vulnerable people, whatever. That started to blow my mind after a while.”

My interview with Davis was the first ever for the ongoing Prison Photography project. It blew my mind too, but in many ways it also prepared me for the contested visual territory within which sites of incarceration exist and into which I had embarked. Davis’ honesty prepared me to face uncomfortable truths and perversions of truth. It readied me for the skeevy power imbalances I’d observe time and time again in our criminal justice system.

The children in Try Youth As Youth may be, for the most part, invisible to society but they are not far away. “I was just acknowledging that this juvenile prison is 20 miles from my home,” says Davis of his earliest motivations. If you reside in an urban area, it is likely you live as near to a juvenile prison, too. Or closer.

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Image by Steve Davis. From the series ‘Captured Youth’

Prisoners, and surely child prisoners, make up one of society’s most vulnerable groups. Isn’t it strange then that rarely are they presented as such? Often depictions of prisoners serve to condemn them, but not here, in Try Youth As Youth.

As we celebrate the committed works of Steve Davis, Tirtza Even, Steve Liss and Richard Ross, we should bear in mind that other types of prison imagery are less sympathetic and that other viewers’ motives are not wed to the politics of social justice. A picture might be worth a thousand words, but it’s a different thousand for everyone. We must be willing to fight and press the issue and advocate for child prisoners. Our mainstream media dominated by cliche, our news-cycles dominated by mugshots and the politics of fear, and our gallery-systems with a mandate to make profits will not always serve us. They may even do damage.

Image: Steve Davis. A girl incarcerated in Remann Hall, near Tacoma, Washington State.

Given that the works of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross circulate in a free-world that most of their subjects do not, it is all our responsibility to handle, contextualize and talk about these photographs and films in a way that serves the child subjects most. It is our responsibility to talk about economic inequality and about the have and have-nots.

“No child asks to be born into a neighborhood where you can get a gun as easily as a popsicle at the convenience store or giving up drugs means losing every one of your friends,” said Steve Liss “They were there [in jail] because there was no love, there was no nourishing, there was anger in startling doses, and there was poverty. Tremendous poverty.”

Image: Steve Liss. Alone and lonely, ten-year-old Christian, accused of ‘family violence’ as a result of a fight with an abusive older brother, sits in his cell.Every day the inmates get smaller, and more confused about what brought them here. Psychiatrists say children do not react to punishment in the same way as adults. They learn more about becoming criminals than they do about becoming citizens. And one night of loneliness can be enough to prove their suspicion that nobody cares.

Davis, Even, Liss and Ross understand the burden is upon us as a society to explain our widespread use of sophisticated and brutal prisons more than it is for any individual child to explain him or herself. The image of an incarcerated child is an image not of their failings, but of ours. We must do better — by providing quality pre and post-natal care for mothers and babies, nutritious food, livable wages for parents, and support and safety in the home and on the streets. Most often, it is a series of failures in the provision of these most basic needs that leads a child to prison.

“Poverty would be solved in two generations. It would require an enormous change in our priorities. Look at how we elevate the role of a stockbroker and denigrate the role of a school teacher or a parent, those who are responsible for raising the next generation of Americans,” says Liss.

(Top to Bottom) Installation shot; video still; and drawings from Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez’s Natural Life, 2014.

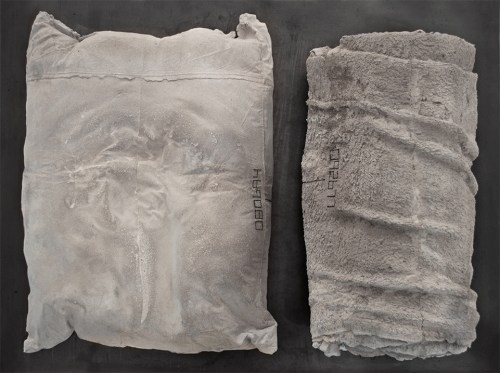

Tirtza Even & Ivan Martinez. Natural Life, 2014. Cast concrete (segment of installation). A cast of five sets of the standard issue bedding (a pillow, a bedroll) given to prisoners upon their arrival to the facility, are arranged on raw-steel pedestals in the area leading to the video projection. The sets, scaled down to kid size and made of a stack of crumbling and thin sheets of material resembling deposits of rock, are cast in concrete. Individually marked with the date of birth and the date of arrest of each of the five prisoners featured in the documentary, they thus delineate the brief time the inmates spent in the free world.

Each of the artists in Try Youth As Youth have seen incredible deprivations inside facilities that do not — cannot — serve the needs of all the children they house. Ross speaks of a child who has never had a bedtime. A social worker once told Davis of one child in the system who had never seen or held a printed photograph.

Documenting these sites is not easy and brings with it huge responsibility. Tirtza Even has grappled with the weight of her work “and how much is expected from them is a little heavy.” In some cases, these artists are the outside voice for children. Liss acknowledges that expectations more often than not outweigh the actual effects their work can have.

“People ask how do you get close to kids in a facility like that. That isn’t the problem. The problem is how do you set up enough artificial barriers so you don’t get too close. So you’re not just one more adult walking out on them in the final analysis,” he says. “I, at least, convinced myself into thinking it was therapeutic for the kids. At least someone was listening to them.”

So far, the efforts of Davis, Even, Liss and Ross have been recognized by those in power. Liss’ work has been used to lobby for psych care and an adolescent treatment unit in Laredo, Texas. Ross’ work was used in a Senate subcommittee meeting that legislated at the federal level against detained pre-adjudicated juveniles with youth convicted of committed hard crimes.

“That’s a great thing for me to know that my work is being used for advocacy rather than the masturbatory art world that I grew up in,” says Ross.

Sedgwick County Juvenile Detention Facility, Wichita, Kansas, by Richard Ross. “Nobody comes to visit me here. Nobody. I have been here for eight months. My mom is being charged with aggravated prostitution. She had me have sex for money and give her the money. The money was for drugs and men. I was always trying to prove something to her…prove that I was worth something. Mom left me when I was four weeks old — abandoned me. There are no charges against me. I’m here because I am a material witness and I ran away a lot. There is a case against my pimp. He was my care worker when I was in a group home. They are scared I am going to run away and they need me for court. I love my mom more than anybody in the world. I was raised to believe you don’t walk away from a person so I try to fix her. When I was 12 my mom was charged with child endangerment. I’ve been in and out of foster homes. They put me in there when they went to my house and found no running water, no electricity. I ran away so much that they moved me from temporary to permanent JJA custody. I’m refusing all my visits because I am tired of being lied to.” — B.B., age 17.

Richard Ross’ works in the Try Youth As Youth exhibition at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

The walls of David Weinberg are not the end point of these works’ journey. An exhibition is not a triumph it is a call to action. The work begins now.

Programming during the exhibition — phone-ins to prison, discussions with ACLU lawyers and experts in the field, conversations with formerly incarcerated youth — will all direct us the right way. The gallery space works best when it sutures artists’ creative processes into a larger process that we can shape as socially informed citizens. Our process of building healthy society.

“Kids need us,” says Liss. “They need our time, they need our involvement, and they need our investment. If you own an automotive shop, open it up to kids and the community. It does take a community.”

There are a host of wonderful arts communities doing work, here in Chicago, around criminal justice reform and social equity — Project NIA, 96 Acres, AREA, Prison + Neighborhood Art Project, Lucky Pierre and Temporary Services to name a few.

The arts can trail-blaze the conversation we need to be having. Photography and film are the ammunition with which we arm our reform arguments. First we see, then we do. If art is not speaking truth to power, then really, what are we doing here?

–

Installation shot of Try Youth As Youth at David Weinberg Photography, Chicago.

–

David Weinberg Photography is at 300 W. Superior Street, Suite 203, Chicago, IL 60654. Open Mon-Sat 10am-5pm. Telephone: 312 529 5090.

Try Youth As Youth is on show until May 9th, 2015.

–

Text © Pete Brook / David Weinberg Photography.

Images: Courtesy of artists / David Weinberg Photography.

Last month, I popped round to Stockholm Studios in NYC and was wrapped in blankets, ginger tea and the ends of a busy shoe rack. And so it was Episode 2.13 of the LPV Show was born.

Tom Starkweather manned the mixing desk while Bryan “Photos On The Brain” Formhals probed with the important matters of the day. I can’t really remember what we talked about in the first half of the show — certainly Prison Obscura, and I recall revealing my fear of Big Brother. We also had a good laugh about all those headlines in photography writing that describe very literally the content of the photographs and immediate crush the mystery and wonder of it all. After demolishing those low-hanging topic-fruits, we moved onto more serious stuff and tried to position Peter Van Agtmael’s Disco Night Sept 11. We concluded it was one of the best — if not the best — photobooks about modern war to have emerged in the 21st century.

LPV just busted out four posts that relate: the show itself, a selection of images from Prison Osbcura, a selection of spreads from Disco Night Sept 11, some photographs of my mug and the recording in session, and (bizarrely, but lovingly) an LPV curation of my Instagram images.

It’s a right laugh getting together in ACTUALLY IN PERSON and having a conversation. You should try it!

It’s also nice to know that there is a small amount of accountability attached to your answers as it will be published and exist, for all of time, in Big-Brother-Big-Data-Centers in the deserts of the Southwest.

My thanks to Bryan and Tom for inviting me round.