You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Press’ category.

The Sybil Brand Institute for women, Los Angeles. Photo Credit: LA County Arts http://www.lacountyarts.org/civicart/01_First_District/1_ela_s_sbi_ppdt_davis.htm

The fixations of Prison Photography on the infrastructural order of sites can as easily be applied outside of carceral space. The Center for Land Use Interpretation has terminus container ports, petrochemicalscapes, first responder training sites, landfill waste streams, pacific coastlines, nuclear proving grounds and even the Trans-Alaska pipeline covered by roving reconnaissance.

There is even a brief field report from the Angola Prison Museum, but I’ll have to come back to that.

I’d like to present the archive for the CLUI’s 2001 exhibit, On Locations: Places as Sets in the Landscape of Los Angeles.

Have you ever questioned the fabric of prison environments in TV or film? There were plenty prison (visiting room) scenes in The Wire, but I was too engrossed in episodes to pay the backdrop any mind. Well, this should get you thinking.

Filming in active prisons is generally not permitted for obvious reasons, and as a result, prison sets are built in soundstages, back lots, and inside other locations. A few prisons in Los Angeles are currently closed, and are regular filming locations. The Sybil Brand Institute, at the County Sheriff’s complex in City Terrace, east of downtown, was the primary Los Angeles County correctional facility for women before it closed in 1997. Though still managed by the sheriff’s department, it is now used exclusively for filming.

Credit: CLUI. Sybil Brand Institute's visiting area has appeared in several films.

Built in 1963, Sybil Brand was a minimum to maximum security facility, with a design capacity of 900, and a peak occupancy of 2,800. It once housed Susan Atkins (whose confessions to a cellmate at the prison led to the arrest of Charles Manson and family), and Susan McDougall of Whitewater scandal fame. When Sybil Brand closed, inmates were transferred to the new Twin Towers complex. The County may renovate the building and open it again as a prison, but in the meantime it offers modern looking prison rooms including cafeterias, hallways, recreation areas, visiting areas, infirmaries, and cells from solitary confinement to dormitories. As it was a women’s prison, the interior walls have a pink color, which is usually painted over for filming.

Productions film here at a rate of two or three per month. The film Blow, about cocaine dealers, recently spent five weeks shooting all over the prison. Other productions include Arrest and Trial, Gangland, X-Files, and America’s Most Wanted.

Though older and more run down, the City of Los Angeles jail in Lincoln Heights is also closed, and is used regularly as a film location, appearing in NYPD Blue, Unsolved Mysteries, and other film and television projects.

Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times. VISITING ROOM: L.A. County Sheriff's Deputy Jack McClive peers through safety glass, while standing in the visiting room, during a tour of the Sybil Brand Institute Women's Jail in Monterey Park.

… or put another way, the apparently unassailable problem that is Guantanamo only amounts to 2% of the actual problem.

This is only one of the many astounding facts I learnt from following the Guardian’s Slow Torture series.

I particularly valued this half hour podcast in which an expert panel of legal professionals discuss the cyclical, “odious” and often ludicrous procedures for trials based on ‘secret evidence’. Clive Stafford Smith has many valuable things to say about American legal protocols. He has represented detainees at Guantanamo Bay and says that, in the overwhelming majority of cases, ‘secret evidence’ used against terrorism suspects does not stand up to judicial scrutiny.

The majority of the Slow Torture series looks at British ‘secret evidence’ trials, how it affects the lives of terror suspects and the consequent erosion of Britain’s legal reputation:

The UK government’s powers to impose restrictions on terror suspects – without a trial – amounting to virtual house arrest have been condemned as draconian by civil liberties campaigners. In a series of five films, actors read the personal testimonies of those detained under Britain’s secret evidence laws and campaigners and human rights lawyers debate the issues raised.

Basically, the same problems embroiled in the acquisition and control of “sensitive” evidence exist on both sides of the Atlantic and are ultimately putting our societies at more of a long-term risk.

Photography alone is worthless. Interviews, think-pieces, investigation, theatre, video, debate, political fight and direct action make issues reality.

What are we to do with our Gitmo preoccupations when the real problem has been moved to Bagram, Afghanistan by President Obama?

Cornell Capa, to some extent, lived in the shadow of his older brother Robert. I guess, it is easy for complacent men to adore the still and fallen martyr than to keep apace with a passionate and piqued practitioner. Cornell’s and Robert’s legends are one; Cornell ceaselessly fought his brother’s corner authenticity debate surrounding The Falling Soldier.

Cornell’s indebtedness to his brother was fateful and self-imposed:

Disappointingly, it is only in extended surveys of Cornell Capa’s career that mention of his fifties photojournalism in Central and Southern America arises. Otherwise, Cornell is celebrated for his political journalism and particularly his campaign coverage of Adlai E. Stevenson, Jack and Bobby Kennedy. Cornell’s photographs from Latin America are often neglected, even demoted.

The Kennedys were the foci of American progressive attitudes, and so, in the sixties, Cornell documented the concerned politician. Cornell was (not in a negative way) passive and the sixties were not formative. It was in the fifties that he actively worked to define the persona, the ideal: ‘The Concerned Photographer’.

Cornell’s work in Latin America:

In 1956, Cornell was in Nicaragua reporting on the assassination of President Anastasio Somoza García. Somoza was shot by a young Nicaraguan poet; the murder only disrupting slightly the Somoza dynasty that lasted until the revolution of 1979 (that’s where Susan Meiselas picks up).

In the aftermath of the assassination over 1,000 “dissidents” were rounded up. The murder was used as an excuse and means to suppress many, despite the act being that of one man.

I have no knowledge of what happened to these men after Cornell photographed them and I am sure you haven’t the patience for speculative-art-historio-speak.

I do wonder … if having witnessed revolution, early democracies, military juntas, coups, communism, social movements, grand narratives and oppression in various forms, if Cornell picked his subjects with discernment back in the United States.

As early as 1954 Cornell was working on a story for Life about the education of developmentally disabled children and young adults. Up and to that point in time, the subject had been regarded by most American magazines as taboo. The feature was a breakthrough.

In 1966, in memorial to his brother, Robert, and out of his “professed growing anxiety about the diminishing relevance of photojournalism in light of the increasing presence of film footage on television news” Cornell founded the Fund for Concerned Photography. In 1974, this ideal found a bricks and mortar home on 5th Ave & 94th Street in New York: The International Center for Photography.

This institutional limbo that eventually gave rise to one of the world’s most important photography organisations was not a quiet period for Cornell. In 1972, he was commissioned to Attica, NY, to document visually the conditions of the prison. Capa presented his evidence to the McKay report (PDF, Part 1, pages 8-14) the body investigating the cause of the unrest. Cornell narrates his personal observations while showing his photographs to the commission.

At a time when, the photojournalist community seems to have crises of confidence and purpose at an alarming rate, it would be wise to embrace his spirit in full recognition his slow accumulation of remarkable accomplishments.

Rest In Peace, Cornell.

PHOTO CREDITS.

Robert F. Kennedy campaigning in Elmira, New York, September 1964. Accession#: CI.9685

New York City. 1960. Senator John F. KENNEDY and his wife, Jackie, campaigning for the presidency. NYC19480 (CAC1960014 W00020/XX). Copyright Cornell Capa C/Magnum Photos

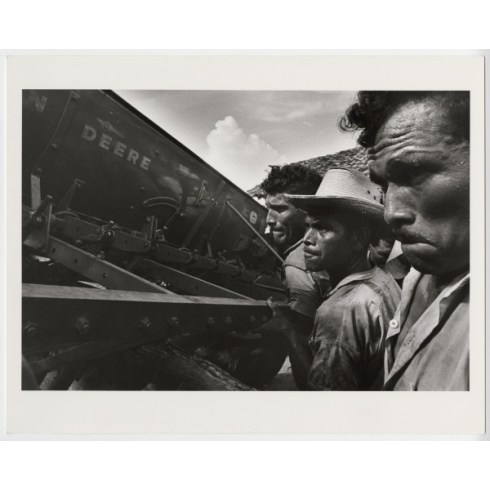

Three men pushing John Deere machine, Honduras, 1970-73. Accession#: CI.3746

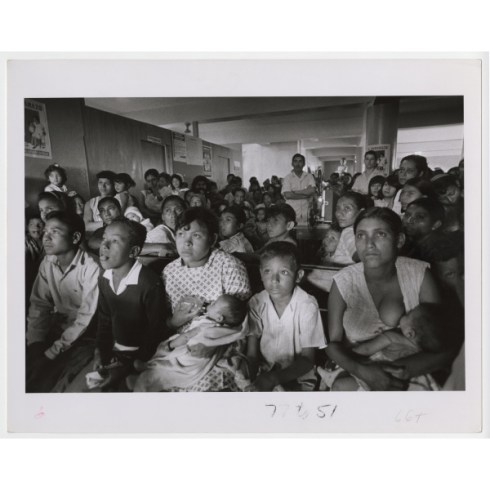

Watching family planning instructional film at Las Crucitas clinic, Tegucigalpa, Honduras], 1970-73. Accession#: CI.8544

Political dissidents arrested after the assassination of Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Somoza, Managua, Nicaragua, September 1956. The LIFE Magazine Collection. Accession#: 2009.20.13

NICARAGUA. Managua. 1956. Some of the one thousand political dissidents who were arrested after the assassination of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza. NYC19539 (CAC1956012 W00004/09). Copyright Cornell Capa/Magnum Photos

Prisoners escorted from one area to another, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, March 1972 (printed 2008). Accession#: CI.9693

Two men walking around prison courtyard, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, March 1972. Accession#: CI.9689

Inmates playing chess from prison cells, Attica Correctional Facility, Attica, New York, March 1972. Accession#: CI.9688

Man on scooter carrying coffin, northeastern Brazil, 1962. Accession#: CI.8921

All photos courtesy of The Robert Capa and Cornell Capa Archive, Promised Gift of Cornell Capa, International Center of Photography. (Except for ‘The Concerned Photographer’ book cover; the Jack Kennedy photograph; & the second Nicaragua prison photograph.)

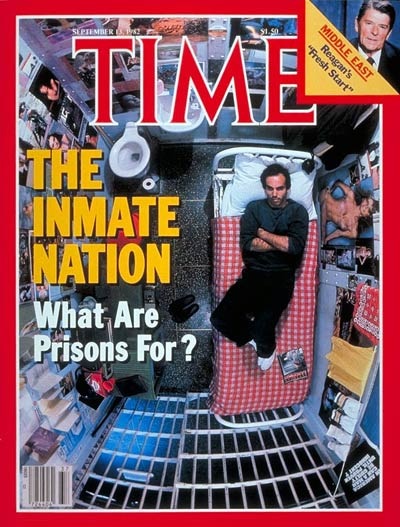

I recently came across this 1982 Time Magazine cover. It immediately reminded me of Juergen Chill’s Zellen series that I blogged about some months ago.

Time Magazine Cover, September 1982

The early eighties signal the end of innocence for America’s criminal justice system. Reagan ushered in an era of extreme punitive sentencing and the most rapid prison expansion of any democratic society ever. That said, you’d hope that with 27 years experience under our belts we’d have some firm answers for the 1982 journalist, huh?

© Juergen Chill

View all Monday Convergences

I don’t envy Chris Parks. If, according to him, he was never in the military (which I believe), then he got a pretty rough ride when stepping back on US soil. This week, the busiest and best free newspaper about went with The Accidental AWOL, a story on Chris Parks.

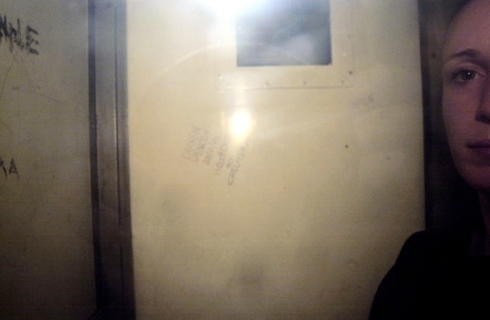

Chris Parks by Kelly O. in the Stranger

The interesting thing about Parks’ story is his processing through multiple legal stages and sites. He was held by other state agencies until he could be accommodated at Fort Knox military base and was then just dumped into the daily military procedures that keep recruits actively docile. And he’s in that until the military realise they’ve lost much of the pertinent information to the case.

In italics below I have quoted author Jonah Spangenthal-Lee directly, but added my own subheaders.

Charlotte Douglas International Airport, NC (Time Detained: “Several Hours”)

Parks had been heading back to Seattle after a trip through Central America with a group of friends. As he passed through customs at Charlotte Douglas International Airport in North Carolina, agents from the Department of Homeland Security, pulled Parks out of line, handcuffed him, and detained him for several hours before taking him to the Mecklenburg County Jail without a word as to why.

Mecklenburg County Jail (One Week)

Parks spent a week in the county jail. After two days, he found out why: At customs, a computerized database had flagged Parks as an AWOL U.S. Army soldier who’d been missing since 2002. Because of his “fugitive” status, he would eventually be transferred to the personnel control facility at Fort Knox. The problem: Parks says he was never in the army.

“Years ago, I signed up to enlist in the army,” Parks said. “Before I actually flew out to basic training, I talked to my recruiter and explained to him I didn’t want to go.” He was just out of Freeman High School in Rockford, Washington—a suburb of Spokane—at the time and had been drawn in by the offer of a $10,000 signing bonus. But ultimately, he says, “All I wanted to do was just snowboard and screw around and be a kid for a while.”

Fort Knox’s personnel control facility (Two Weeks)

Parks was sent to Fort Knox’s personnel control facility, where his head was shaved and he was issued fatigues and a blanket, given a bunk, and instructed not to talk to any of the women in the facility or other soldiers on the base. “I basically had to play army,” Parks says. “You have to fall in and stand in line. I had no idea what the hell I was doing.”

After a total of three weeks, Parks was released with little explanation. And after three weeks of procedural but unjust detention due to bureaucratic failings, the military are still going to send Parks the bill for his flightfrom Charlotte to Fort Knox! And his head was shaved …

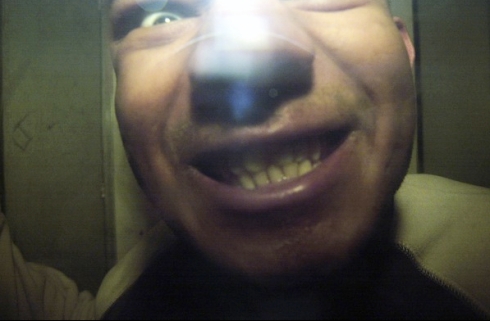

I grinned ear to ear yesterday when Foto8 In & Out the Old Bailey ran Ben Graville‘s work of remand prisoners (and security guards) in reaction to the press camera up against reinforced glass. It is a novel, clear and entertaining project. Why did it take someone so long to put a series like this together?

If photography is – in cases – intended to plumb the human soul and aggressively seek out human frailty, pride, conversion, obstinacy, etc., then the back of a cop-van is probably a good place to start. Folk on their way to trial are going to have a lot to say about a) their charge b) their case c) everything else that the first two don’t cover.

James Luckett over at consumptive coined the term “Photo booth from Hell” and he’s right on the money. They sit in a big white box subject to a camera behind a small glass rectangle. The environment is claustrophobic, impersonal and germy.

If a prisoner has the forethought or experience they may ready him or herself for the photograph. If not they’ll be captured on film anyway.

How balanced is the interaction between camera and subject? The image will serve the media more than it will serve the balance or accuracy of the court case. But this is a truism.

Graville is interested in state enforced anonymity and the effect it has on mystifying and intensifying understanding;

It should be no shock that many prisoners perform, gurn and address Graville’s camera directly; they are – literally and legally – in a transitory, undecided state. If I was in this same situation, I think it would be a natural reflex-come-obligation to self-represent to the camera. These prisoners may not have chosen to have the camera in their space, but they have the choice of how to address it.

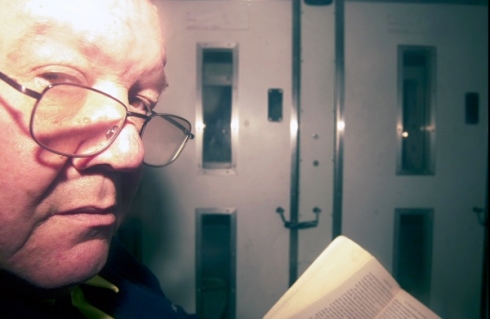

… and of course there’s always a security guard who gets in on the action.

Photography in prisons and jails isn’t always edgy nor riven with fraught emotion. Sometimes it can be quite ordinary. In fact, given the utter boredom of most prison facilities it would be good to see a photo essay that communicated effectively vacuous time and psychological space.

…but, I digress. Hetherington, over at the venerable What’s The Jackanory?, indulged in some “shameless self promotion” of his magazine work at North Branch Correctional Institution. Within the Wired article, Prisoners Run Gangs, Plan Escapes and Even Order Hits With Smuggled Cellphones, Hetherington’s images include a cell-tableaux, sniffing dog and bagged phone. I am more interested in the non-published images Hetherington provides in his post; they’re crisp, pared down images of inmate and interior.

Andrew Hetherington for Wired

It got me thinking about how the environmental fabric – along with the representation – of American prisons has changed.

When (documentary) photographers first began accessing prisons – Danny Lyon, Conversations with the Dead (1971), Jacob Holdt; Taro Yamasaki, Inside Jackson Prison (1981) – the conditions were poor. And prisons were only one response to criminal behaviour and social contract.

Even latterly, Ken Light shot the black & white, in-your-face and sweaty Texas Death Row (1994) and in doing so romanticised historicised American prisons as definitively dirty sites of “the other”. By the 1990s, though, the US had implemented long term custodial sentences as the primary “solution” to crime. The phase-out of Federal parole beginning with Reagan and culminating with Clinton bloated the Federal Bureau of Prison (BOP) population, alone, from 40,000 to 200,000.

So two trends intersected: Prison populations swelled resulting in overcrowding and economically efficient facilities were rapidly being built. The mass construction of new warehouses prisons altered the spatial experience of confinement and the nature of interpersonal interaction within. Cell tiers were replaced by AdSeg wings.

The BOP has a reputation for housing the hardened criminal and specialises in high security facilities. Additionally, from the late 1980s states were building their own new high security and supermax prisons. This new penological architecture replaced 40 foot brick walls and watch towers with razor wire and motion sensors.

Prison environments are sparse. Problems with dark corners & damp have been replaced with the psychotrauma of constant fluorescent light. Problems with stashed contraband have been replaced with an absence of surfaces to set down objects. Denim uniforms have been replaced by sweat outfits. The penological management of gangs & group violence has been replaced with the pharmacological management of locked-up basket cases.

One former inmate of the Federal Supermax facility in Florence, Arizona (ADX) has described it as the “Perfection of Isolation.”

Correctional Officer Jose Sandoval inspects one of the more than 2,000 cell phones confiscated from inmates at Calfornia State Prison in Vacaville, California. Rich Pedroncelli / AP

Telephoning a way out Isolation

“Cell phones,” says James Gondles, executive director of the American Correctional Association, “are now one of our top security threats.” (Wired, July, 2009)

I posited in the past that cell phones were just one part of the prison economy and their commodity status was in direct reaction to the cost of corporate-managed prison payphone systems – in essence a racket in response to a racket. However. having read the Wired article it is clear how much of a serious security threat cell phones pose to prison authorities.

The majority of tactics for isolation, perfected over the past 30 years by prison administrations, are rendered immediately obsolete,

With a wireless handset, an inmate can slip through walls and locked doors at will and maintain a digital presence in the outside world. Prisoners are using voice calls, text messages, email, and handheld Web browsers to taunt their victims, intimidate witnesses, run gangs, and organize escapes—including at least one incident in Tennessee in which a guard was killed. An Indiana inmate doing 40 years for arson made harassing calls to a 23-year-old woman he’d never met and phoned in bomb threats to the state fair for extra laughs.

So what’s the answer? Debate exists over the value and legality of jamming all signals around prisons but a High School in Spokane, WA proved localised signal-jamming a bad idea when it interfered with the local Sheriff’s radio signals.

We should also bear in mind that ‘The 1934 Communications Act prohibits anyone except the federal government from interfering with radio transmissions, which now include cell calls.’ (Wired)

Criminalize Smuggling but Not Talking

TIME does a good job of breaking down the stats and describing the evolution of the problem. It is obvious that authorities are going to make strategic response to a growing trend but prison authorities must not compromise the already limited opportunities for inmates to talk with friends and family. Close family ties and contact are key to reducing recidivism and giving former prisoners the best means to integrate back into society.

And of course, inmates aren’t the only ones caught up in the illicit trade of cell phones in prisons. One California prison guard admittedly to making over $100,000 in a year through smuggling and selling cell phones!

On that note, I offer you a CDCR sanctioned news VT.

As so very often, the spark of thought was ignited by the Change.org Criminal Justice blog.

In the interests of full disclosure, DuckRabbit and Prison Photography have become virtually-close these past couple of months, beginning with an acknowledged shared politic, via encouraging support, to a mention in DuckRabbit’s announcement of a daring competition that I feel I had only a small part to do with.

I am not advertising DuckRabbit’s $1,000 competition for brevity’s sake. I am promoting it because:

a) Stan Banos had an excellent point in the first instance

b) DuckRabbit has not been shy to challenge inequalities before (including MSF – opening dialogue, discussing visual ethics and celebrating consequent positive representations on MSF’s photoblog)

c) PDN, with an all-white 25 juror panel has a valid charge of passive racism to answer.

d) I think it is a ballsy move, and I want to see what comes of it.

Up for the debate?

FOR $1,000 YOU MUST;

“Come to PDN’s defense and answer the question, ‘What possible, plausible excuse could exist for an all white jury from a publication of such influence?’”