You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Rehabilitative’ category.

From ‘Assisted Self-Portraits’ (2002-2005) by Anthony Luvera.

PHOTOGRAPHY’S NOT JUST DEPICTION!

There’s a fascinating discussion to be had at Aperture Gallery this Saturday December 7th. Collaboration – Revisiting the History of Photography curated by Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, and Susan Meiselas is an effort to draft the first ever timeline of collaborative photographic projects. Items on the timeline have been submitted either by members of the public or uncovered during research by Azoulay, Ewald, Meiselas and grad students from Brown University and RISD.

“The timeline includes close to 100 projects assembled in different clusters,” says the press release. “Each of these projects address a different aspect of collaboration: 1. the intimate “face to face” encounter between photographer and photographed person; 2. collaborations recognized over time; 3. collaboration as the production of alternative and common histories; 4. as a means of creating new potentialities in given political regimes of violence; 5. as a framework for collecting, preserving and studying existing images as a basis for establishing civil archives for unrecognized, endangered or oppressed communities; 6. as a vantage point to reflect on relations of co-laboring that are hidden, denied, compelled, imagined or fake.

Within the gallery space, Ewald and co. will discuss the projects and move images, quotes and archival documents belonging to the projects about the wall “as a large modular desktop.”

The day will create the first iteration of the timeline which will continue to be added to.

“In this project we seek to reconstruct the material, practical and political conditions of collaboration through photography — and of photography — through collaboration,” continues the press release. “We seek ways to foreground – and create – the tension between the collaborative process and the photographic product by reconstructing the participation of others, usually the more *silent* participants. We try to do this through the presentation of a large repertoire of types of collaborations, those which take place at the moment when a photograph is taken, or others that are understood as collaboration only later, when a photograph is reproduced and disseminated, juxtaposed to another, read by others, investigated, explored, preserved, and accumulated in an archive to create a new database.”

I applaud this revisioning of photo-practice; I only wish I was in NYC to join the discussion.

As you know, I celebrate photographers and activists who involve prisoners in the design and production of work. And I’m generally interested in photographers who have long-form discussions with their subjects … to the extent that they are no longer subjects but collaborators instead.

Photographic artists Mark Menjivar, Eliza Gregory, Gemma-Rose Turnbull and Mark Strandquist are just a few socially engaged practitioners/artists who are keen on making connections with people through image-making. They’ve also included me in their recent discussions about community engagement across the medium. I feel there’s a lot of thought currently going into finding practical responses to the old (and boring) dismissals of detached documentary photography, and into finding new methodologies for creating images.

At this point, this post is not much more than a “watch-this-space-post” so just to say, over the coming weeks, it will be interesting to see the first results from the lab. If you’re free Saturday, and in New York, this is a schedule you should pay attention to:

1:00-2:00 – Visit the open-lab + short presentations by Azoulay, Ewald and Meiselas.

2:00-2:45 – Discussion groups, one on each cluster with the participation of one of the research assistant.

2:45-4:00 – Groups’ presenting their thoughts on each grouping.

4:00-4:30 – Coffee!

4:30-6:00 – Open discussion.

6:00 – Reception.

If any of you make it down there and have the chance, please let me know what you think and thought of the day.

Photography has innumerable uses, but one of its greatest qualities is it’s ability to tell stories. Sometimes that is through direct description of events and sometimes through evocation of emotion through colour and form.

In the rare cases when photography is used as a rehabilitative artistic tool for incarcerated peoples, straight documentation may be effected (even manipulated) by control and access privileges put in place by a prison administration. In the case of incarcerated youth, the essential and appropriate legal control which prevents identification of a child means that photo-education must be purposefully designed.

That is why when projects of light painting emerge from detention facilities such as the Rhode Island Training School (RITS), I applaud the invention and persistence of AS220, the Providence-based arts non-profit that conducts the program.

Writer and photographer Katy McCarthy published a gallery of the AS220/RITS’ light paintings on the excellent JJIE Bokeh blog recently.

“In the striking images from AS220‘s If These Walls Could Talk, the magic made is not an illusion. Like a surrealist painting, the manipulated photos employ metaphor and symbol,” writes McCarthy.

The images are like electric bolts from the darkness; not something we’d necessarily expect but that is because our imagination may not soar like those of imprisoned children.

Photography has glorious potential to unlock the emotional needs of locked up youth. (A few weeks ago, I featured the work of those locked up in New Mexico, enrolled in the Fresh Eyes Project.) However, given the dearth of photo-education in juvenile detention facilities in the U.S., I can only conclude that the sensitivities to publication/distribution, and the road-blocks to getting a potentially security-threatening camera inside any prison inhibit the development of programs such as those run by AS220 at RITS and The Fresh Eyes Project in NM.

Are we missing massive opportunities to connect by not embracing the camera as we would embrace, say, a pen or paintbrush? Clearly, much more goes into helping children through emotional and behavioural difficulties — rounded and relevant education, vocational skills, counseling, substance abuse help — yet propping up these efforts is the need to steady emotional and self-esteem needs says Anne Kugler, AS220 Youth Director.

“Unless you address underlying emotional issues you can put all the services in place that you want and it doesn’t mean that they’ll necessarily be able to move through adolescent development in a positive way. That’s where I think self-expression and creativity come in. Unless children have the experience of being recognized for doing something creative and good it’s a hard road; inside in their heart they must feel there’s a purpose to moving forward with education and counseling,” says Kugler.

Youngsters are responsible for the lion’s share of the 1.3 billion images made everyday worldwide. It seems a little perverse to deny photo-based activities and visual literacy to incarcerated youth, no? Especially as it’s so relevant.

“When you watch young people with cameras they immediately want to use them,” says Kugler. “They know how to do so. They want to get their hands on the camera and they want to take pictures of themselves and they love being able to see — especially with digital cameras — their pictures right away. It’s fun and very accessible. Bear in mind, there are some children who — because of self-esteem issues — feel a sense of horror if you ask them to write a poem or draw a picture, but I think a photo in particular has accessibility that works great out there.”

Bravo to AS220. And let’s see more programs for incarcerated youth like AS220’s If These Walls Could Talk! A special shout out to Scott Lapham and Miguel Rosario who coordinate and teach the If These Walls Could Talk program.

Check out Young Incarcerated Photographer Make Magic In Photos

All photos: Courtesy of students of the AS220 RITS photography program.

Photo: Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange

In 1981, freelance photographer Karen Ruckman stepped inside the notorious medium-security Lorton Prison to teach prisoners photography. Lorton was a sprawling barrack-like institution nestled in a rural pocket of the Virginia suburbs. Lorton, a Federal facility, closed in 2001. For decades it was where Washington D.C. sent its convicted felons. Initially, the administration didn’t think the program would last more than a few sessions and the students were cautious. Ruckman successfully won grants, donations from Kodak, cash from private donors, and support from then Mayor’s wife Effi Barry to support the photography workshops. Ruckman taught at Lorton until 1988.

When I recently learnt about Ruckman’s work, I was floored. For the longest time I have said that photography workshops inside of American mens prisons ended in the late seventies and mass incarceration had precluded the mere chance. Ruckman’s work at Lorton has forced me to reevaluate my timeline. I hope Ruckman’s work also brings you encouragement.

In 1985, Ruckman invited cameraman Gary Keith Griffin to film the class at work. Now, she and Griffin are working on a documentary about this unique moment in prison arts education. Ruckman and Griffin have followed some of the men since their release and the film, tentatively titled InsideOut, is slated for release in 2015 — the 30 years after Gary made those first reels.

Ruckman has routinely worked with populations considered to have less of a voice in our society – battered women, the poor, and at -risk youth for example. She also taught photography in the D.C. women’s jail, but that single summer program doesn’t feature in the film.

Karen Ruckman and I spoke about her access, the program’s successes and obstacles, the need for diverse image-makers in criminal justice and the lessons the project contains for us all three decades on.

Scroll down for our Q&A.

Photo: Calvin Gorman. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Calvin Gorham

Q&A

Prison Photography (PP): I wasn’t aware of any prison photography workshop programs after the 70’s and so to find your work at Lorton is a revelation. It’s 25 years since the program ended, so let’s start with the basics, how did you get involved? Where did the idea come from?

Karen Ruckman (KR): I was doing work for the Volunteer Clearinghouse here in D.C. and they sent me to the prison to photograph volunteers who were tutoring inmates. I went to Lorton with George Strawn, the head of volunteer services and he asked if I’d be interested in teaching a class. I hadn’t really thought about it, but it happened to coincide with the funding for proposals coming in to the D.C. Arts Commission and I applied for a career development grant and I got it, much to my surprise.

I went down once a week and taught photography with a focus on career development. I approached it as a basic photography class and I brought in guest speakers, photographers from various newspapers, friends of mine in the community who were photographers. It went very well. The men worked hard, so after that I applied for another grant. Actually, D.C. had a category called ‘Arts in Prison’ during the 80s. I got my later funding through that grant category.

PP: Which photographers visited the class?

KR: Craig Herndon, from the Washington Post; Bernie Boston, from The Los Angeles Times, Gary Keith Griffin who works primarily in video and is working with me on the feature documentary now. I had executives from NBC who came in too, as well as local artists and fine arts photographers.

PP: What other arts program were being taught in D.C. prisons at the time?

KR: There were several theater programs and a woman who taught painting. That’s pretty much it.

Photo: Bernard Seaborn. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Bernard Seaborn

PP: How did the program develop over the 8 years? Did the funding, scope or size of the class change?

KR: I had a cap on how many students I could have but I ended up doing two classes. Prisoners who had been in the earlier classes then became mentors to the new guys. Over time, I became more of a facilitator: bringing in supplies, bringing in expertise, working with them, training them and then they took on the job of mentoring each other.

They also ran the dark room when I wasn’t there. We built a dark room in a closet that was in the prison school where classes took place. I had a teaching assistant, Chuck Kennedy, who came with me from the community but I also had a prisoner who was a teaching assistant so the guys could work during the week. The program grew with more men participating, more prisoners developed skills. The inmates took on more of a teaching role; it was always my goal that they would.

PP: How many students would you say you taught over the seven years?

KR: I tried to figure this out once some years ago! More than 100 but less than 200. We had new intakes for each class and some guys stayed in year after year. They’d been charged for felonies in D.C. Some had written bad checks, others had been charged for murder.

PP: Lorton is now closed?

KR: It was closed in 2001. It was a rather controversial move. The prison was actually located in Virginia on hundreds of acres of land. There were different facilities there including two youth centers, Central, the medium security facility where I taught, and maximum. Virginia had been wanting that land for quite some time.

Lorton’s buildings needed a lot of work, and rather than renovate, they closed it. The Federal government transferred the land to Virginia and now D.C. prisoners are farmed out across all of the country.

PP: Ouch! That can’t be good for rehabilitation.

KR: It’s terrible, yes. And so there’s no programing, and they’re in federal facilities all over the country.

Photo: Sidney Davis. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Sidney Davis

PP: What was the reaction and the response from the prison authority? Today, of course, these programs don’t exist and often the language-of-security is used to deny all sorts of things within prisons, and the camera in particular is quickly labelled as a security hazard. What was the feelings of the Lorton authorities at that time?

KR: I had to take on the job of educator. Many didn’t understood the need for the men to go outside the classroom to photograph, and the usefulness of exhibitions. They understood the photo class but part of that, part of each class was doing a show. We always did one in the community and one in the prison — it was a massive job of educating staff about how we could go about producing the program successfully.

I was very fortunate because Effi Barry, the mayor’s wife, had just opened an art gallery and I had her support. I always went top down. It took me a lot of time to go through the necessary channels and to get the permissions. The administrator at Central Facility, Salanda Whitfield, was a really nice guy who supported the program. He died some years ago.

Mr. Whitfield let the program come in, he let us break the rules, because of course cameras weren’t allowed, and of course inmates were not allowed to take photographs. Even with his backing I still had lots of paperwork to do in order to make the classes function well.

I found some resistance from the guards who felt like the inmates were getting something that was too nice, that wasn’t fair, that they shouldn’t get. So, my real problem when I had problems was always from the guards.

Photo: Michael Moses El. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Michael Moses El

Photo: Calvin Gorman. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Calvin Gorham

PP: Before you began the project, did you consider yourself an activist in that field of criminal justice?

KR: No, I was an activist generally but not particularly in prison reform.

PP: Did you ever have visitors that were inspired by the program and wanted to replicate it elsewhere? Or were you working in a bubble?

KR: I guess I worked in a bubble. I mean, I had visitors and help from others. I had photographers come in, other artists as well, but, no, I didn’t have anyone that wanted to replicate it.

PP: Did you understand at the time that you were doing something very pioneering?

KR: I don’t think so. I mean it was a really interesting time. Many of us were doing things in the community and were trying to think sideways, and I felt like it was something exciting. I had a passion about taking the camera to people who couldn’t normally tell their stories. By giving the men in my program this powerful communication tool, it was an opportunity for them to tell people who they were, it was a humanizing agent.

For the documentary, and since 2001, we’ve followed up with two of the men who were in Lorton and the program.

Michael Moses El had a fascination with guns. He found that when he came into the program that he was able to transfer this fascination with guns to the camera. It was a very exciting thing for him.

Calvin Gorham is an artist. He’s a singer; a soulful person and he used photography as an artistic tool to communicate how he felt. He said he saw a lot of dark things in the prison and he photographed to express that.

PP: And so there’s no doubt in your mind that photography is a rehabilitative tool?

KR: It’s a powerful rehabilitative tool. There are so many levels one could do with it as a storytelling device. Now, with digital imaging, possibilities are unlimited. Yes, absolutely. I worked with other groups in the city. In 1988, I also worked with women at D.C. Jail, then in the 90s with women at a pre-release halfway house. Also, women in various shelters and at-risk kids.

PP: And so tell us about the documentary, it’s been thirty years since you’ve been doing this work, how and why did you decide a documentary was necessary?

KR: In 1985, Gary Griffin, a friend and colleague, bought his first TV camera. Gary thought it would be valuable if we could do video about the program. So I got permission again, days of paperwork, but we went in with a crew for a week in 1985.

Some of the footage in the trailer is from ’85. We never were quite sure what it was going to be. We did put together a fundraising piece because I was always having to raise money.

Photo: Michael Moses El. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Michael Moses El

PP: Right, you were constantly communicating with free society how important your work was and asking for help?

KR: To do the programing, I had to constantly write proposals and fundraise. I was somewhat burnt out by the end of the 80s. The funding for the prison program became very difficult to get. I went on to work with other groups and do different things. The guys would stay in touch with me, they had my business phone and they’d call me when they got out of prison and tell me what they were up to.

But, I still have the wonderful images. I was at a workshop in Santa Fe in the late 90s and showed some of the images to National Geographic photographer Sam Abell. I also had an audio tape from one of the graduations that I put with the images and it was a very powerful slideshow (of sorts) — one of the men at one of the graduations gave a marvelous speech about photography.

Sam was excited by the images and very supportive. He said. “You’ve got to do something with this.”

I decided along with my video production friends to do a reunion. We knew Lorton was closing. I tracked down as many of the guys as I could. We had about 20-25 at the reunion. Gary documented the reunion and then we documented some of the men periodically. We later settled on following Michael and Calvin.

Photo: Calvin Gorman. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + Calvin Gorham

PP: Why Michael and Calvin?

KR: Number 1, they were interested in participating. Number 2, they’re very interesting people — Michael is business-oriented, very focused about his life. Calvin’s a musician, we have a lot of footage of him singing. We’ve seen them almost every year since 2001. Gary and I think 30 years is a good amount of time. When we get this feature documentary completed by 2015 it will have been 30 years since Gary began filming.

PP: The documentary is a few things, it seems? A record of a moment; the on-going stories of Michael and Calvin; and a call to action asking people to think about photography’s relationship to educational and rehabilitation?

KR: It is. It’s a character study that presents the power of photography, the power of art, and how important both can be in changing lives.

Only a few of the men now make pictures professionally, but they all make pictures still. The documentary is about the program and how the learning experience has stayed with the participants throughout their lives; how it continues to resonate and define their world view in a positive and powerful way.

The discipline required working in the dark room was critical. For example, one participant, David, spent two years learning how to make a good print. And he ultimately made beautiful prints. Two years. It was very impactful.

Photo: David Mitchell El. © Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange + David Mitchell El

PP: Can you give us your thoughts of storytelling, self-representation and empowerment?

KR: It was always their story to tell. I came in, I gave them cameras. I didn’t take a lot of pictures. I was there as a facilitator. I gave them the tool to tell their stories. I think that’s enormously important.

During that period — and even now — there’s something that is bothersome to me when people go in and take pictures of powerless people. It’s important for people to tell their own story; that doesn’t just shift the viewer, it shifts the person telling the story.

PP: It does seem obvious that if one puts a camera into the hands of someone in the community that you’re trying to bring new information about and to the wider world, but there’s still so many people in the photo world who reject that.

KR: Yes. This is off topic, but probably the most amazing experience I had when I took exhibitions to the community was when I hung a show by women at a shelter for victim’s of domestic violence. We did a show of their work at the D.C. library, in the mid-90s. Visitors would ask me who took the photographs, and when I explained the women photographers were survivors of domestic violence, people would just stop and walk out of the room.

How do we relate to issues that we’re uncomfortable about? Do we not want to see these individuals?

PP: Well, what were attitudes like then about crime? What was the reputation of Lorton? What was the general community’s view of Lorton prison?

KR: Lorton and the D.C. community were very connected in the eighties. So many people from the city were incarcerated there that Lorton was just like a subset of the community. So, there wasn’t as much stigma with prisoners as I encountered among other groups that I worked with, at least in D.C. at that time.

Lorton was considered a very dangerous place. The facilities were old even when I was there. The men lived in dorms and there was one guard per dorm at night so you can imagine that there was some violence. I personally, I didn’t get too involved in that. I tried to go in and do my program with them without judgement.

Photo: Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange

PP: And then tell me about the dark room? Were there any issues with taking chemicals and other apparatus in?

KR: The dark room was fabulous! I brought the supplies and the men ran the dark room. Kodak gave me film and photographic paper. I bought chemicals. We had lots of applicants, but I could only take so many, so it was considered a reward for someone to get into the photography program.

PP: On what criteria did you decide admission?

KR: They had to have good behavior to be allowed in the program. When it started out I only admitted men that were within three years of parole because the lessons were about career development; it was my hope to actually help guys get jobs once they got out. After a while, we relaxed that rule and a few guys still had a lot of time to serve.

PP: And could students be removed from the program at the whim of the warden or the staff?

KR: Well, I lost a few people because they misbehaved in prison and were sent to the hole (solitary confinement), or to another prison. That happened.

PP: When you release the documentary have you got any plans for distribution. How do you plan to reach audiences?

KR: I’m taking that a step at a time. We are going to finish a 30-minute short this winter that we’ll take to film festivals. A local organization, Docs In Progress, is hosting a showing of the trailer. I’ll contact our local PBS station, but with the feature-length film I have to plan a more structured distribution plan. It’s very important to get it out. I’ve stayed in connection with people in the D.C. community, people like Marc Mauer at the Sentencing Project and others who care about the issue.

PP: What’s your personal position on prisons? What role does incarceration play in our society?

KR: There are people who commit violent crimes and they belong in prison. Some of the men that I worked with said that being in prison gave them an opportunity to really look at themselves and take a timeout and to correct their behavior. There is a role for prison if they have rehabilitation programs.

Of course, we all know that there are way too many people that are incarcerated and there are people that are incarcerated that just shouldn’t be there, so it’s very frustrating. Things haven’t changed all that much since the eighties except we’ve incarcerated more people.

D.C. incarcerates an enormous number of people. With the poverty and lack of good public education here. That’s the story of the documentary. Calvin’s son went to prison and Michael’s son went to prison. So, we talk about that story, it’s that legacy that’s just, it should be broken. Marian Wright Edelman‘s work with the Children’s Defense Fund deals with this issue, and has a program called the Cradle to Prison Pipeline.

Photo: Karen Ruckman/PhotoChange

PP: Do you think the American public gets reliable information on prisons?

It’s my sense that most people aren’t interested in prisons. When I tried to raise money for the program it was very hard. There’s little compassion. Around drugs and drug culture there’s some alternative sentencing programs happening but by and large, I don’t think people are interested. I mean, now, we have for-profit prisons which is even more atrocious because now we have to maintain the population so that profit lines can be maintained.

PP: I ask because, to my mind, if there were more photography programs like yours occurring in our prisons today, there would exist a more nuanced view of prisons; prisoners’ views. We’d all be in a better place in terms of being informed.

KR: Yes, absolutely. The program had a humanizing effect, both on the participants and in how they were viewed by the community. It provided a bridge, and it didn’t cost the tax payers much. I secured small grants and fundraised and so it was for tax payers a really good deal. That’s true of most arts programming.

PP: Often program funding is based on measurable impacts but a lot of time with prisons you can’t measure those so easily because some people are not getting out for ten or twenty years. You can’t correlate arts rehabilitation with recidivism because the prisoners don’t get out in any short space of time. So, what stories do you have about your students? Any stand out stories that convince you of the efficacy of a photography program?

KR: The men would be the ones to tell you. Sadly, a lot of the guys die; they don’t make it. Some of them die soon after they get out.

I think about Calvin and Michael — the program gave them discipline and an opportunity to evolve productively. Michael told us about a time soon after his release when he was very tempted to commit a violent act against another man. Something stopped him. It was, he said, it was the discipline and working relationships that he had developed during the program. He didn’t want to end up back at Lorton.

A couple of the guys do a lot of professional photography. It’s very hard to answer that question because people want to ask, “Okay, well how many guys got a job as a photographer?”

PP: How many people generally get jobs as photographers!

KR: Actually, Michael was hired by US News and World Report to shoot a cover story on poverty, and he took some amazing pictures. They were going to use one of his photos for the cover but when they found out he was an ex-offender they wouldn’t run his photo. He’s still very bitter about that.

PP: What’s his past history got to do with the suitability of a photograph?

KR: It was many years ago; it was the late 80s.

PP: But that’s complete discrimination.

KR: I was told by several photographers at the Post that they would be uncomfortable to have ex-offenders there because they would be afraid that they would steal equipment. These are the attitudes that make it really tough for ex-offenders to get jobs in fields other than construction or the food industry, though a few of them do get jobs driving Metro buses.

PP: Is there anything I’ve missed?

KR: I appreciate you finding and highlighting the work. We’re excited about finishing the film. The project has ended up — without me realizing it — a life work.

FOLLOW

You can follow Karen and Gary’s development of the film via the InsideOut website, on its Facebook page, Tumblr page and via Karen’s Twitter.

TRAILER

Yellow Hand With Orange Glow. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

The potential for photography to change the lives of the incarcerated, particularly the young prisoners, is significant. Photography education provides all the therapeutic tenets of arts programming, but also develops new skills; visual literacy, computer and digital-darkroom skills, and (of course) the not-too-simple task of mastering the settings on a camera. Photography workshops flex different muscles than painting or writing workshops may. Photography allows storytelling beyond the pen and the paintbrush.

NOTE: I discuss many photography programs in this article, but all the images are by incarcerated children in New Mexico who’ve participated in the Fresh Eyes Project workshops.

THE FRESH EYES PROJECT

The Fresh Eyes Project in New Mexico is two years old. It delivers 10-week classes, twice a year in two New Mexico facilities – the Youth Diagnostic and Development Center (YDDC) in Albuquerque and the adjacent Camino Nuevo Correctional Center.

The planning, structure and accountability reported on the Fresh Eyes Project website is impressive.

Volunteer programs, cameras or not, must be water-tight, well-designed and directed. The Fresh Eyes Project clearly states its scope of work, it’s objectives, its internal assessment and feedback opportunities for students. I very much appreciate programs that share curriculum and lesson plans. Very valuable.

“Our purpose is to help the youngsters to see themselves and the community into which they would be released with fresh eyes as and for the community to see the youngsters with fresh eyes not as ‘the Other’ but as ‘our own,'” says the Fresh Eyes Project founder, Cecilia Lewis.

SCARCITY OF PROGRAMS INSIDE JUVENILE DETENTION

Sadly, projects like the Fresh Eyes Project are rare. In America, inside locked facilities there have been some occasional photography workshops but few consistent ones. I’ve mentioned many times Steve Davis’ workshops (there’s still so many photographs that remain unpublished). Fatima Donaldson recently led a digital photography workshop at Fort Bend Juvenile Detention Center, Texas (info and video).

Probably the best and most consistent provider of photography workshops to incarcerated youth is AS220 in Providence, Rhode Island. AS220 delivers education, including photography training, at the Rhode Island Training School (RITS), the State’s only juvenile detention facility. Classes are delivered as part of AS220’s Youth Photography Program which also works out of a downtown location and in local schools too.*

The Fresh Eyes Project and AS220’s work are the only year-on-year prison photography programs delivered in the U.S. that I know of. Please, contact me if there’s current programs of which I should know.

Fear. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

Ghost Hand. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

These Bars Keep Me In. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

PHOTOGRAPHY FOR YOUTH STORYTELLING

Can a teen do without their phone? Is a phone ever without camera these days? Can that commonplace visual communication be leveraged to spark interest in other forms of image making? In other cameras? In film photography? I’d say so.

Thanks largely to the work of Wendy Ewald, literacy and personal development through photography is a familiar notion. Youth storytelling photo programs include Youth in Focus, Seattle: Focus on Youth, Portland; Critical Exposure, Washington DC; First Exposures, San Francisco; The In-Sight Photography Project, Vermont; Leave Out ViolencE (LOVE), Nova Scotia; Inner City Light, Chicago; My Story, Portland, OR; Picture Me at the MoCP, Chicago; and Eye on the Third Ward, Houston; and Emily Schiffer’s My Viewpoint Photo Initiative.

This summer, at Photoville, I saw an exhibit Perspectives featuring the photographs of teens from Red Hook, Brooklyn. Perspectives came out of a specific PhotoVoice program, that itself is part of the ongoing JustArts Photography Program (formerly the Red Hook Photo Project)

The JustArts Photography Program (more here and here) is run through the Red Hook Community Justice Center (RHCJC) in cooperation with New York Juvenile Justice Corps and the Brooklyn Arts Council. As with all the RHCJC projects, the photography program exists to improve the lives of teens within the geographically and socially isolated Red Hook neighbourhood.

PHOTOGRAPHY AS INTERVENTION

Whereas JustArts uses photography as inspiration, working with kids from less advantaged communities to envision great futures, Young New Yorkers actually uses photography (as well as video, illustration and design) as intervention in the cogs of the youth justice system.

“Young New Yorkers a restorative justice, arts program for 16- and 17-year-olds who have open criminal cases. The criminal court gives eligible defendants the option to participate in Young New Yorkers rather than do jail time, community service and have a lifelong criminal record. The curriculum is uniquely tailored to develop the emotional and behavioral skills of the young participants while facilitating responsible and creative self-expression.”

Young New Yorkers (YNY) is remarkable. More to come on Prison Photography about their successes. This little shout out is the least YNY deserve.

If you want to support YNY’s work right now, their Second Annual Silent Art Auction is on October 16, 6-10pm, at Allegra La Viola Gallery, 179 East Broadway, New York, NY 10002. You can bid online, if you’re not in New York.

So much good work being done across the country. These kids are our future.

Fin.

Shadow Portrait. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

On The Outside. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

Portrait Of My Teacher. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

Scary Hands. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

Mighty Me. Courtesy: Fresh Eyes Project

———————————————————

* A couple of years ago, I interviewed the director of AS220 youth programs, two of the photography instructors and a few kids. They also gifted me a portfolio of work and I’m long overdue to scan and present that material here on the blog. Please, stay tuned.

———————————————————

I came across the work of the Fresh Eyes Project thanks to an article Capturing Captivity From The Inside, by Katy McCarthy for the Bokeh Blog on the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange.

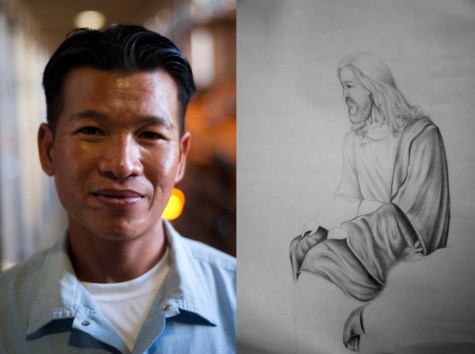

A temporary gig as a set photographer took Jordana Hall to San Quentin State Prison; her heart and consciousness propelled countless return visits. She has worked particularly closely with men who were convicted when juvenile (under 18) and were sentenced to life in prison.

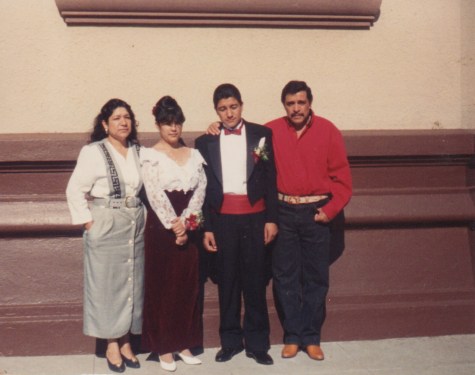

Hall has worked as a volunteer in existing programs; launched her own project that melds poetry, family letters, snapshots and her own portraits; and visited the hometowns and families of prisoners. The ongoing body of work Home Is Not Here is part of Hall’s senior thesis exhibition. It will be on show – beginning April 2013 – at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

I wanted to learn more about Hall’s motives and discoveries.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Prison Photography (PP): How did you get access to San Quentin State Prison?

Jordana Hall (JH): My work at San Quentin started in June 2011. I was hired as the set photographer for a documentary (working title, Crying Sideways) by SugarBeets Productions. The documentary details the stories of a group inside San Quentin called KIDCAT (Kids Creating Awareness Together).

PP: KIDCAT is a group of lifers sentenced as juveniles, correct?

JH: Yes, you can follow KIDCAT on Facebook.

PP: They describe themselves as “men who grew up in prison and as a group have matured into a community that cares for others, is responsible to others, and accountable for their own actions.”

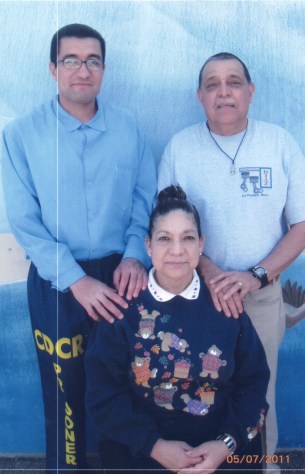

JH: I began attending KIDCAT’s bi-weekly group meetings as a volunteer. During this period of volunteering, I developed a working relationship with the members of KIDCAT. Showing up when I said I would, being accountable, and most of all keeping an open mind and heart while inside re-assured the men of KIDCAT that I was a trustworthy member.

Then in June 2012, I started working on my senior thesis for my Photojournalism BFA at the Corcoran College of Art and Design. I approached Lieutenant Sam Robinson, Public Information Officer at San Quentin, with the idea of starting the “Home Is Not Here” project. If I had not had the relationship that I do with the men of KIDCAT, Sam would not have been so willing to help. It really is this relationship that I have with the group that has allowed me so many opportunities to continue my work there. I’ve been going into San Quentin for a year and a half now, and have only been able to bring my camera three times.

To be granted access to San Quentin – even minimal access – requires a lot of work. There needs to be a legitimate return for the prison community. In my case, publishing my work to Young Photographer’s Alliance, posting to my website, and eventually in an exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art was enough justification for the prison to allow me to continue working inside.

I never take my access for granted.

There are strict rules about what you can and cannot do, wear and say. If I slip up – even just a little – my access is on the line.

PP: Why did you take on the project?

JH: After hearing the inmate’s stories during the documentary filming, I realized that all of them were just teenagers who were dealt a bad hand. This is not to say they don’t take responsibility for what they did. They definitely do. Their stories resonated to my core; the stories would impact anyone who heard them. I left the prison gates that day realizing that they could be my brother, father, or best friend. I began to think about their families. Most of the men in the group are in their mid-thirties; they have spent more than half of their lives in prison. I thought about how they struggle to keep working relationships with their loved ones for so many years through the prison walls. That wondering led me to my senior thesis project.

Home Is Not Here documents the relationships between an incarcerated person and his family. I seek out the ways in which their relationship can be kept when there are so many barriers involved.

PP: What have you learnt?

JH: I’ve learned that the families of incarcerated people are the least documented victims of crime. Communities shun them for “raising a criminal.” There are limited resources available for them to get help. These families mourn the loss of their loved one’s free life with little to no support.

I learned the truth in the statement, “When one person is incarcerated, at least five people ‘serve the time’ with them.” I have seen family members go about their daily lives with a piece of their heart locked away in prison.

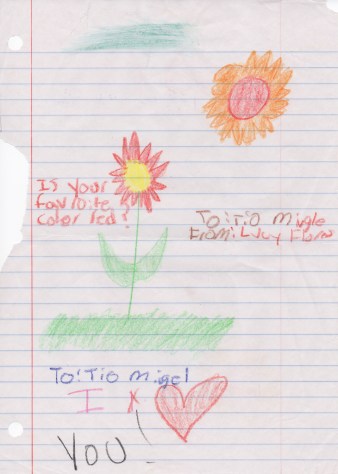

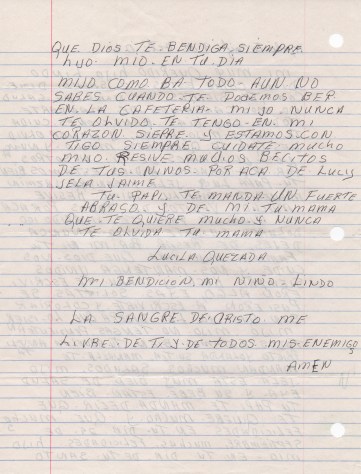

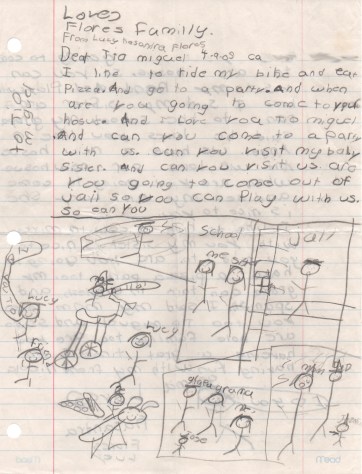

JH: I learned that letters from a child to their “Tio Miguel” (who they have never met outside of prison visitations) would break your heart. I learned that even the toughest looking men still get tears in their eyes when you ask about their family.

I am still learning.

PP: What did the prisoners think of being photographed?

JH: The first day they were most interested in seeing how a digital camera works. I am very hands-on with my subjects, and with the permission of Lt. Sam Robinson, I handed my second camera body to the guys to play with on the breaks during filming. It was both funny as well as saddening to watch their amazement at the foreign device.

The first time I went in, I asked to see an inmate’s cell. The guys all looked at each other, waiting for someone to volunteer. One by one they denied my request to see their space. We ended up going to a stranger’s cell, just so I could poke my head in from the door. Soon after, I fully realized the shame that comes over them when asked about their cells. It is the only space that is their own, but it also the cage they are locked in at night. These 6 x 12 cement cages are a place both of safety and of degradation.

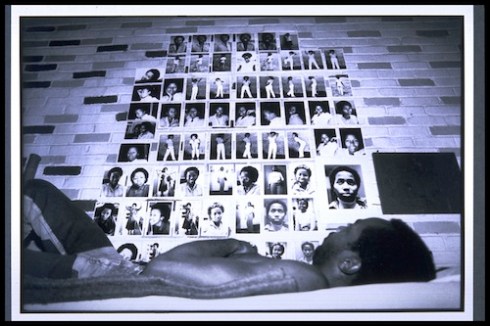

After I stuck around for a year, I approached the cell situation, again. This time they were excited to show me their space. Their family photos on the wall, bookshelf with notebooks, sketchbooks, and wall markings left from previous inmates. “Stay Focused” was scrawled into the yellowed paint next to the metal bunk. It took some time and a lot of trust building for me to get on that level with them.

PP: Did you give the men prints?

JH: Giving the guys the prints is absolutely one of my favorite parts!

The Home Is Not Here project had me traveling to the hometowns of three men. I went with only small clues of what and where to photograph – “The Dairy Queen where I took my first girlfriend on my first date,” or “The restaurant named after the city in Vietnam where my family was from.”

When I brought back prints from my trips, the guys were blown away by how much had changed, and how much had stayed the same.

I was asked by one inmate to visit the grave of his grandmother. They were extremely close and she passed away while he was in prison. When he saw the photograph I took there, he began to cry. It was almost as if I had delivered him a physical place to grieve her passing.

I try to give back to my subjects as much as I can. I try not to be that photographer that comes in, gets the story, and never comes back. They give so much of themselves when they allow me to photograph them, giving prints to them is the least I can do.

PP: What did the staff think of being photographed?

JH: I never photographed the staff, although some day I hope to see some really thorough work done about the people who work in prisons. It would be a fascinating story.

PP: I agree. I’ve yet to see a photography project that suitably deals sympathetically and deeply the complex and stressful dynamics of correctional officers’ work and lives.

PP: Could photography serve a rehabilitative role, if used in a workshop format in prisons?

JH: I think a workshop on photography in a prison would be an incredible idea. These men are so introspective and have so much to offer, creatively. The documentation of life inside prison by an inmate could offer such insight for us all.

PP: Are prisoners invisible?

JH: Yes, I believe prisoners are invisible. Everything about the prison system is set up for them to be invisible, and stay invisible. To be silenced, and out of sight. What I aim to do with this project is to shed some light on a piece of an inmate’s life that is not seen. When people think prison photography they think of hardened criminals, drug addicts, grimy hands gripping cell door bars, and the underbelly of society. I am offering the alternative viewpoint, which is the humanity inside. These men are fathers, sons, brothers, friends, and they all have people who care about them. They also have built communities of support for each other, inside.

PP: What’s been the feedback to your the work?

JH: As I work I like to get feedback from my peers. A lot of people who see photographs of inmates and due to their preconceived notions will shake their head and walk away thinking, “What monsters…” but with the work I do, I try to side step this notion and say, “No, look closer.”

No matter what I do, some people will never see it the way I’d like them to, but for people who can be open-minded, the work gives an inside look to the humanity that exists inside prison, and awareness of the struggles of their families.

PP: Anything else you’d like to add?

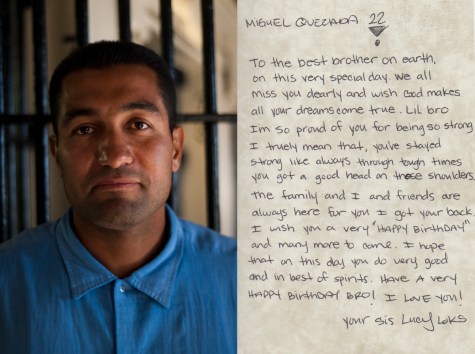

JH: As I move forward in my thesis, I am turning my focus to just one inmate in particular, Miguel Quezada. This is the working statement:

“Estamos Contigo (We Are With You)” – Miguel Quezada (below) was incarcerated at age 16. Now 31, he has spent half of his entire life in prison. Due to a harsh judicial decision that he should serve his sentences consecutively, his first parole hearing is not until the year 2040. He will be 60 years old. Home, for Miguel, rests between the realities of life at San Quentin Prison today, memories of his childhood cut short, and dreams of a faraway tomorrow. His family shares this stress, mourning the loss of their loved one’s free life. From the part of South Modesto, California known for its lack of sidewalks and high crime rate, Miguel grew up in poverty with his parents who immigrated from Mexico. His mother and father, Arturo and Lucila, are almost completely illiterate, so writing letters takes a lot of time and energy. Miguel appreciates it when they do write, but loves when they send photographs. His nieces and nephew, who he has never met outside of prison visitations, write him frequently and give him a sense of connectivity to the outside world. Miguel is one of hundreds of men in the state of California with similar stories – serving life for a mistake made as a teenager. The barriers of the prison walls will never restrain the emotional longing of one human being to be with another.

PP: We look forward to checking in again soon. Thanks, Jordana.

JH: Thank you.

Adrian Clarke‘s portraits of female former prisoners in the UK are up front and honest. The ladies insisted they go on the record and speak openly about their experiences in HMP Low Newton, an unremarkable small prison for women and young offenders in the north of England. Each woman reported only good treatment during their incarceration.

Clarke’s work is not sugar-coated. He doesn’t have the answers and his subjects, some of whom have ongoing drug addiction struggles, are searching for them.

The women – although aware of their tough lives – do not paint themselves as victims. They want to step up and take responsibility but when you’re that far down it takes a Herculean effort to wright the ship.

Low Newton, like all good portrait series, offers insight. But it does not tie the loose ends. I am left to wonder about the different definitions of normalcy we carry in our day today lives and if these women will find their own versions of normalcy and stability.

Mostly, Low Newton deserves attention because it appears to reflect a complete respect between photographer and subject.

Adrian Clarke’s portraits of female former prisoners are in the latest issue of The Paris Review.