You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Visual Feeds’ category.

If you’re strolling around the centre of Charlottesville these next few days and peep a red newspaper box, reach inside and grab yourself a copy of the free paper within.

Accompanying his exhibition of Some Other Places We’ve Missed at The Bridge: Progressive Arts Initiative in Charlottesville, artist Mark Strandquist has created eight pages of photos, activist resources and a call to engage.

I have a vested interest in promoting this newspaper. For it, I wrote an editorial about the history of — and imperative of — photographers and artists working in American prisons. It is reproduced in full below.

Even if I wasn’t personally involved, I’d still be singing the praises of Mark’s work – I’ve posted about Some Other Places We’ve Missed before and I am including the work in a prison photography show next year. When Mark and I chatted about the exhibition of Some Other Places We’ve Missed, we got all giddy about the fact that his show is outside of the official LOOK3 program, and yet he is able to grab some mindshare among the throng of photobodies in Charlottesville this week.

© Mark Strandquist. A photograph made of a scene described by an incarcerated male.

ART AND SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT

For the longest time, photojournalism and documentary work has pursued common good, reliable information, hidden stories and social change. At least, that’s the ideal. With guests such as Susan Meiselas and Martha Rosler, and with Koudelka’s exhibit, the LOOK3 schedule looks serious and seriously good.

Mark and I are huge fans of this year’s LOOK3 line up, but LOOK3 remains a big festival where the cucumber martinis flow like wine and big name photographers will hold court in Charlottesville town center. Festivals are about learning, meeting and sometimes brown-nosing … and, for that, we love them. Everyone leaves photography festivals feeling connected and re-energised and that’s how it should be. But, there’s more.

Some Other Places We’ve Missed asks us to think about image-making in slightly different ways. Not everyone can produce a 20 foot tall Nat Geo vinyl banner, but everyone can have the type of intimate conversations on which Some Other Places We’ve Missed is based. Of course, I am biased because Mark is having conversations with American prisoners and I think there’s rehabilitative value in that.

I’ll stop prattling on now and just say if your interest is piqued then you should attend the panel talk More than A Witness – Photography as Social Engagement on June 15, 2pm – 3:30pm. Speakers are David Levi Strauss, Chair of Critical Studies at the School of Visual Arts, Edgar Endress of Floating Lab Collective, Yukiko Yamagata of the Open Society Foundation, and Matthew Slaats, Executive Director of the Bridge. They’ll discuss how art facilitates dialogue and can be used to reach out to new subjects and engage broader audiences. Find out more on Facebook here.

Mark has programmed a busy schedule of events at The Bridge including a poetry reading and discussion between gallery-goers and prisoners via a direct feed from a local jail. Full details on The Bridge website.

[Scroll down for my newspaper editorial.]

Installation shot of Some Other Places We’ve Missed, opening night at The Bridge, Charlottesville, VA.

EDITORIAL: DRAWING ON MEMORY, WORKSHOP GETS PRISONERS AND PUBLICS THINKING ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHY, STORY AND HIDDEN SPACE

In the 1970s, a purple barge floated up and down the Hudson River in New York state. Once moored, photographers emerged to teach workshops to communities traditionally outside of art circles; hospital patients, rural high-schoolers and — perhaps most remarkably — prisoners. The buoyant vessel with living and gallery spaces was operated by the Floating Foundation of Photography (FFP).

Not all New York State prisons are on the Hudson and so after initial offerings at Sing Sing, FFP ventured inland, eventually delivering photographic arts education in eight prisons. The majority of workshops were facilitated by founder Maggie Sherwood, her son Steve Schoen and a handful of close associates. But, the FFP enjoyed close ties with the New York arts scene and as such invited leading photographers in recent memory to deliver day-long workshops in the prisons – W. Eugene Smith, Arthur Tress, Mary Ellen Mark, Les Krims, Judy Dater, Lisette Model and Lee Witkin to name a few. The FFP mounted exhibitions of “outsider photography” on the anchored barge in Manhattan and in Central Park.

As one browses the images and stories within Some Other Places We’ve Missed, perhaps it is worth bearing in mind the history of arts education — and specifically the role of photography — in the rehabilitation of those locked up within our prisons and jails. The Floating Foundation represents a particular high point in this history; the access into prisons that it negotiated, the pedagogy it employed, and the optimism it eschewed stand out as extraordinary. These days, opportunities for arts education (with strong photographic components) in the prison industrial complex are rare. As such, projects such as Mark Strandquist’s deserve attention.

In the 1980s, mass incarceration began. In the past 35 years, the number of Americans locked up has more than quadrupled. The war on drugs, indeterminate and longer sentencing, broader definitions of criminal behaviour, the decimation of many safety-nets for society’s most vulnerable, and the politics of rhetoric and fear all contributed to the tumorous growth of America’s prisons. Even in states that entered a prison building boom, facilities were soon overcrowded. As costs soared, pressures mounted and efficiencies took priority, both the ability to provide — and belief in — the efficacy of education and arts to help in the rehabilitation of prisoners waned.

States previously provided high school and college education to prisoners as item lines on their budgets. These were scratched from budgets early, and when the Clinton administration revoked prisoners’ right to federally funded Pell Grants in 1994, the message was clear: prisons exist to incapacitate, not to rehabilitate. The majority of college level education provided in state prisons these days is administered by either earnest non-profits, University departments with social justice mandates, and sometimes the two in partnership. Prisons remain legally obliged to enroll prisoners without high-school diplomas into GED programs, but the success of students already alienated by public schooling often hampers success. To speak generally, it is the limited scope of — and limited opportunities for — education in prison that scupper advancement. To wright this ship, a huge shift in political will, informational (media) exchange and tax-payer attitude is required.

Prisoners are lining up to be part of this collective shift of consciousness. “Lucky” prisoners may live in state facilities close to a big city which can draw on volunteers to run programs previously provided by the state. Others find opportunities designed for successful reentry toward the end of their terms. But still, the majority of American prisoners have little to no voice and are for all intents and purposes invisible. Existing creative outlets include law libraries (although not in private prisons), pen-pal programs, and vocational work (prison factories remain because of the immediate profits they create), but these are programs that should exist for all and form merely first rung of the ladders to self-improvement and broadening of the mind.

Some Other Places We’ve Missed brings to us the voices, regrets, dreams and imagination of just a small number of men incarcerated in Richmond County Jail. Mark Strandquist provides us a bridge into their worlds. One needn’t share the political position of an artist to recognize the imperatives of a work or an action; intellectual curiosity and community engagement can saturate the entire political spectrum. Strandquist’s work is sadly exceptional, but it needn’t be. Perhaps, his tenacity is exceptional, but I believe it is within reach of us all. Whenever possible we should be thinking of ways that we can engage with our nation’s prison population. It is a population that has been strategically manipulated to the point of invisibility.

Cameras are a security tool for prison administrations, but in the hands of others are a security hazard. The ability to see, frame and witness life behind bars inherently involves power. In mugshots, in surveillance and in tightly-controlled visiting room digital portraits, prison authorities have a near monopoly on such power. Only rare and serendipitous moments (usually a sympathetic superintendent) give rise to an artist being permitted to use a camera in prison space — Robert Gumpert, Kristen Wilkins, Jenn Ackerman and Jeff Barnet-Winsby are a few examples.

Strandquist navigated this potential barrier by conducting a photography workshop without any introduction of cameras into the classroom. His simple question, “If you had a window in your cell, what place from your past would it look out to?” acted as proxy to any release of the shutter. He asked students to think photographically. While the images are made by Strandquist beyond the prison walls, the essential discussions about memory, self-reflection, the power of photography and the comfort of the image all inform the project.

Through Strandquist’s photographs, we the public, are given an opportunity to connect with the incarcerated; their imagined windows become, momentarily, our window into their lives. But the 1/125th of a second needed to make a photograph is a perverse fraction of the months and years many spend imprisoned. Are the photographs enough? On their own, probably not. But the collaborative and educational core to the project is considerable. As audience, we should employ the same amount of imagination as Strandquist’s students and consider similar ways we can engage with incarcerated persons. There is every reason to think Strandquist’s methodology can be replicated in prisons and jails across the nation. With 2.3 million men, women and children behind bars Some Other Places We’ve Missed should also be a prompt for us to meditate on the millions of sights and experiences in American prisons that we never witness.

“The neighborhood was middle class, nice, where everyone knew everyone. One great lady taking care of us all – grandmother; Big Momma for short. The house set on fire when one cousin playing with matches. Had to move into government owned property. Family split up. Never as close as before. Miss the love. Home base.”

BIOGRAPHY

Mark Strandquist is a multi-media artist and curator based in Richmond, VA, who creates work that incorporates viewers as direct participants, features histories that are typically distorted or ignored, and blurs the boundary between artistic practice and social engagement. His work has been featured in various film festivals and independent galleries as well as a current exhibit at the Art Museum of Americas in Washington, DC. He is currently working on a BFA at Virginia Commonwealth University. He has a Tumblr.

A few weeks ago I wrote, for Wired, a piece about Edmund Clark‘s latest body of work Control Order House. The piece carried the irreverent title This Incredibly Boring House Is a U.K. Terror Suspect’s Lockdown but the details of the project it gets into – two years of negotiating access, Clark’s process which riffs on surveillance and forensic photography, Clark’s the decision to present every photograph he took in the order he took them, etc. are important, mildly complex and worth getting one’s head around.

The house Clark documented belonged to a pre-trail UK terror suspect, under house arrested, referred to in legal documents as CE.

I wrote:

Control Order House is the only existing photographic study of a residence occupied by a person under a UK control order. It is not an exposé, however. Given the legal sensitivities, every image was vetted by UK government officials. Clark was not allowed to reveal the identity of the terror suspect — referred to in legal documents as “CE” — nor his location.

“To reveal CE’s identity would be an offence and in breach of the court-imposed anonymity order,” says Clark. “All the photographs I took or the documents I wanted to use had to be screened by the Home Office.”

For Clark, the project is best appreciated in its book form. Control Order House was published by HERE Press and released May 2nd.

Clark refers to the book as an “object of control” because at a point, he accepted that, with so many attached limitations, his photography was almost an extension of the state power he was documenting. All of his equipment had to be itemized and registered with the UK Home Office before his three visits.

Wired created a Scribd document (that has no URL, but is embedded in the article) with six pages of Clark’s correspondence with both the terror suspect and the UK Home Office employees.

“Even CE’s lawyers made it clear to me that the I had to careful about what I spoke to him about because the house was (very probably) bugged and that my telephone communication with him would be monitored,” explains Clark. “All my material, even my words here [in this interview] could become part of CE’s case.”

Control Order House is a finely balanced project. It is hampered by so many obstacles to unfettered depiction that our traditional notions of what photography is supposed to do are frustrated. It is not exposé; it is completely descriptive of its own limitations. It’s these limitations from which we must depart in thinking about photography in highly policed spaces. Control Order House should kick-start considerations of lesser seen photographs from the Global War On Terror (GWOT), namely, images of drone strike aftermath, Aesthetics of Terror (as, in this case, distilled by artists), redacted images in magazines distributed at Guantanamo (scroll down), Kill Team trophy photos, American personnel’s own vernacular war photography, and Jihad suicide posters.

Control Order House is about the act of photography. It’s self-referential as kids’ MFA work that deconstructs photographic process, but — unlike those studio experiments — it has roots in a clearly identifiable political territory. It shows us more than we knew but not as much as we would like to know. In so doing it reminds us of all the operations, violence and war crimes carried out on our tax dollar that we never see, never know.

–

UPDATE, 05/14/2013: Harpers Books confirmed that the collection was bought by an individual at Paris Photo LA.

–

At Paris Photo: Los Angeles, this week, a collection of California prison polaroids were on display and up for sale. The asking price? $45,000.

The price-tag is remarkable, but so too is the collection’s journey from street fair obscurity to the prestigious international art fair. It is a journey that took only two years.

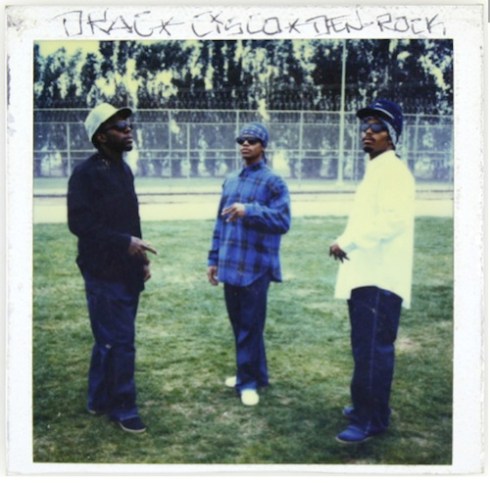

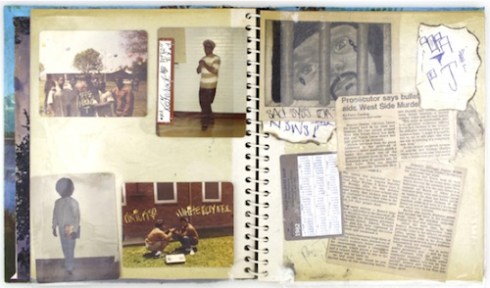

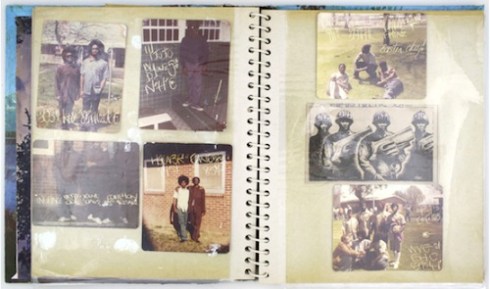

The seller at Paris Photo LA, Harper’s Books named the anonymous and previously unheard-of collection The Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive. Harper’s has since removed the item from its website, but you can view a cached version here. The removal of the item leads me too presume that it has sold. Whether that is the case or not, my intent here is not to speculate on the current price but on the trail of sales that landed the vernacular prison photos in a glass case for the eyes and consideration of the photo art world.

The Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive on display at Paris Photo LA in April, 2013.

FROM OBSCURITY TO COVETED FINE ART COMMODITY

In Spring 2012, I walked into Ampersand Gallery and Fine Books in NE Portland and introduced myself to owner Myles Haselhorst. Soon after hearing my interest in prison photographs, he mentioned a collection of prison polaroids from California he had recently acquired.

You guessed it. The same collection. Where did Myles acquire it and how did it get to Paris Photo LA?

“I bought the collection from a postcard dealer at the Portland Postcard Show, which at the time was in a gymnasium at the Oregon Army National Guard on NE 33rd,” says Haselhorst of the purchase in February, 2011.

As the postcard dealer trades at shows up and down the west coast, Haselhorst presumes that dealer had picked up the collection in Southern California.

Haselhorst paid a low four figure sum for the collection – which includes two photo albums and numerous loose snapshots totaling over 400 images.

“I thought the collection was both culturally and monetarily valuable,” says Haselhorst. “At the time, individual photos like these were selling on eBay for as much as $30 each, often times more. I bought them with the intention of possibly publishing a book or making an exhibition of some kind.”

Indeed, Haselhorst and I discussed sitting down with the polaroids, leafing through them, and beginning research. As I have noted before, prison polaroids are emerging online. I suspect this reflects a fraction of a fledgling market for contemporary prison snapshots. Not all dealers bother – or need to bother – scanning their sale items.

Haselhorst and I were busy with other ventures and never made the appointment to look over the material.

“In the end, I didn’t really know what I could add to the story,” says Haselhorst. “And, I didn’t want to exploit the images by publishing them.”

Another typical and lucrative way to exploit the images would have been to break up the collection and sell them as single lots through eBay or at fairs, but Haselhorst always thought more of the collection then the valuation he had estimated.

In January 2013, Haselhorst sold the collection in one lot to another Portland dealer, oddly enough, at the Printed Matter LA Art Book Fair.

“Ultimately, after sitting on them for more than two years, I decided they would be a perfect fit for the fair, not only because it was in LA, but also because the fair offers an unmatched cross section of visual printed matter. It was hard putting a price on the collection, but I sold them for a number well below the $45,000 mark,” he says.

Haselhorst made double the amount that he’d paid for them.

The second dealer, who purchased them from Haselhorst, quickly flipped the collection and sold it at the San Francisco Antiquarian Book Fair for an undisclosed number. The third buyer, also a dealer, had them priced at $25,000 at the recent New York Antiquarian Book Fair.

From these figures, we should estimate that Harper’s likely paid around $20,000 for the collection.

Harper’s Books’ brief description (and interpretation) of the collection reads:

Taken between 1977 and 1993. By far the largest vernacular archive of its kind we’ve seen, valuable for the insight it provides into Los Angeles gang, prison, and rap cultures. The first photo album contains 96 Polaroid photographs, many of which have been tagged (some in ink, others with the tag etched directly into the emulsion) by a wide swath of Los Angeles gang members. Most of the photos are of prisoners, with the majority of subjects flashing gang signs.

[…]

The second album has 44 photos and images from car magazines appropriated to make endpapers; the “frontispiece” image is of a late 30s-early 40s African-American woman, apparently the album-creator’s mother, captioned “Moms No. 1. With a Bullet for All Seasons.”

[…]

In addition, 170 loose color snapshots and 100 loose color Polaroids dating from 1977 through the early 1990s.

In my opinion, the little distinction Harper’s makes between gang culture and rap music culture is offensive. The two are not synonymous. This is an important and larger discussion, but not one to follow here in this article.

HOW SIGNIFICANT A COLLECTION IS THIS?

Harper’s is right on one thing. The newly named ‘Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive’ is a unique collection. Never before have I seen a collection this large. Visually, the text etched directly into the emulsion is a captivating feature of many of the polaroids.

We have seen plenty of vernacular prison photographs from the 19th and early to mid 20th century hit the market. Recently, a collection of 710 mugshots from the San Francisco Police Department made in the 1920’s sold twice within short-shrift. First for $2,150 in Portland, OR and then for $31,000 in New York just four months later! At the time of the sale, AntiqueTrader.com suggested it “may [have] set new record for album of vernacular photography.”

As a quick aside, and for the purposes of thinking out loud, might it be that polaroids that reference Southern California African American prison culture are – in the eyes of collectors and cultural-speculators – as exotic, distant and mysterious as sepia mugshots of last century? How does thirty years differ to one hundred when it comes to mythologising marginalised peoples? Does the elevation of gang ephemera from the gutter to traded high art mean anything? I argue, the market has found a ripe and right time to romanticise the mid-eighties and in particular real-life figures from the era that resemble the stereotypes of popular culture. It is in some ways a distasteful exploitation of people after-the-fact. Perhaps?

WHERE DOES THE $45,000 PRICE-TAG COME FROM?

Just because the so-called ‘Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive’ is rare, doesn’t mean similar collections do not exist, it may just mean they have not hit the market. This is, I argue, because no market exists … until now.

If the price tag seems crazy, it’s because it is. But consider this: one of the main guiding factors for valuations of art is previous sales of similar items. However, in the case of prison polaroids, there is no real discernible market. Harper’s is making the market, so they can name their price.

“All in all, it’s pretty crazy,” says Haselhorst, “especially when you think about how I bought it here in Portland over on 33rd, just a few miles from our gallery.”

All these details probably make up only the second chapter of this object’s biography. The first chapter was their making and ownership by the people in the photographs. Later chapters will be many. Time will tell whether later chapters will be attached to astronomical figures.

Harper’s suggests that rich “narrative arcs might be uncovered by careful research.” I agree. And these are importatn chapters to be written too.

I hope that more of these types of images with their narratives will emerge. If these types of vernacular prison images are to command larger and larger figures in the future, I hope that those who made them and are depiction therein make the sales and make the cash.

As it stands the speculation and rapid price increases, can be interpreted as easily as crass appropriation as it can connoisseurship. If these images deserve a $45,000 price tag, they deserve a vast amount of research to uncover the stories behind them. Who knows if the (presumed) new owner has the intent or access to the research resources required?

Along that same vein, here we identify a difference between the art market and the preservationists; between free trade capitalism and the efforts of museums, historians and academics; between those that trade rare items and those that are best equipped to do the research on rare items.

Whether speculative or accurate, the $45,000 price is way beyond the reach of museums. Photography and art dealers who are limber by comparison to large, immobile museums are working the front lines of preservation.

“Some might say that selling [images such as these] is exploitation, but a dealer’s willingness to monotize something like this is one form of cultural preservation,” argues Haselhorst. “If I had not been in a position to both see the collection’s significance and commodify it, albeit well below the final $45,000 mark, these photographs could have easily ended up in the trash.”

Loose Polaroids from the Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive as displayed by Harper’s Books at Paris Photo LA, Los Angeles, April, 2013.

A cover to one of the two albums that make up the Los Angeles Gang and Prison Photo Archive.

Video still. On June 10, 2012, Maine Department of Correction’s employee, Captain Shawn Welch sprays OC spray into the face of prisoner Paul Schlosser who is bound in a restraint chair after Schlosser, who has an infectious disease, spat at an officer.

The pepper-spray – dispensed at point blank range – to the face of the restrained prisoner was horrific enough, but it was the use of the spit-mask that truly reflects the vindictiveness of this act of torture. Put on prisoner Paul Schlosser’s face after the pepperspray had doused his mouth, face and eyes, the spit-mask kept the irritant closer. If there was one consistent cry from Schlosser it was that the mask be removed.

Last week, the nation was shocked by video footage of Captain Shawn Welch, a Maine correctional officer discharging oleoresin capsicum (OC) spray, without warning, into the face of Paul Schlosser. Welch held the Mark 9 canister about 18 inches away. The Mark 9 is intended for disabling multiple people at a distance of no closer than 6 feet.

Some experts say the use of pepper spray can be a reasonable way to get control of a situation, even if a person is restrained, but in this case is seemed wholly unnecessary. It seems vindictive and personal.

The incident occurred in June 2012 and the video came public following a leak. The Portland Press Herald broke the story. Welch was initially sacked but later reinstated following an appeal that took into account his service to the Maine Department of Corrections. It is scandalous that this man returns to a uniform.

The incident occurred in June 2012 and the video came public following a leak. The Portland Press Herald broke the story. Welch was initially sacked but later reinstated following an appeal that took into account his service to the Maine Department of Corrections. It is scandalous that this man returns to a uniform.

Furthermore, as Press Herald OpEd argued the MDOC hunt for the source of the leak missed the point. The issue is the abuse the video shows.

The Press Herald’s coverage of the story has been thorough and I quote from it comprehensively below. The matter that stood out for me was the investigator’s observation that the confrontation became personal between Welch and Schlosser.

In the 24 minutes between Schlosser being sprayed and when he can wash the spray off his face, Welch strolls in and out of the cell holding the OC spray canister, telling Schlosser that if he doesn’t cooperate, “this will happen all over again.”

“You’re not going to win. I will win every time,” he says.

Welch says repeatedly, “If you’re talking, you’re breathing,” suggesting that as long as Schlosser was complaining, he was not in serious medical distress. Welch does call for a member of the prison’s medical staff.

At one point, he whispers to Schlosser, “Useless as teats on a bull, huh … What do you think now?” an apparent reference to an insult Schlosser directed at him two days earlier, according to the investigator’s report.

The investigator concluded that Welch’s treatment of Schlosser was personal.

“Welch continues to brow beat Schlosser and it looks like he has made this a personal issue,” said Durst in the report. “There is not one incident of de-escalation and in fact Welch continues to escalate the situation even after the deployment of chemical agent.”

Schlosser had been self-harming and refusing medical attention, actions which led to the extraction from his cell by riot-gear-clad prison guards.

Welch told an investigator that the use of pepper spray was appropriate because Schlosser, who has hepatitis C, had spit at an officer.

Schlosser gasps and fights for breath. He tries to lean forward to spit out the spray, but the guard holds his head against the back of the chair. One of the guards then puts a spit mask on Schlosser. The mask traps the irritant against Schlosser’s face, at one point covering both his mouth and nose.

Schlosser says he can’t breathe and promises not to struggle or argue anymore.

Pepperspray instantly dries out mucous membranes in the eyes, nose and mouth causing intense and overwhelming pain. Pepperspray leads to a sensation of not being able to breathe, although a National Institute of Justice study found it does not compromise a person’s ability to breathe.

“It’s just like getting jalapeno pepper in your eye, only multiplied by a bunch,” said Robert Trimyer, a use of force instructor and OC trainer with the University of Texas Health Science Center Police Department in San Antonio. Depending on the concentration, OC spray is roughly 300 times “hotter” than a jalapeno pepper.

“It’s painful, but it goes away. The people that have the problem breathing, it’s really more of the anxiety involved,” said Trimyer.

Yerger believes that putting the spit shield on top of the pepper spray would intensify the effect of the spray.

“I have never heard of any trainer I have ever worked with as a peer that would ever say, ‘Put a spit hood on someone after pepper spraying them,'” he said.

“They’re spinning out of control. Restraint, pepper spray, now cover their face — you’re just escalating the situation. In cases I’ve reviewed when people have died in a (restraint) chair, it’s not uncommon to see factors like that involved.”

DIRIGO

Above Schlosser’s restraint chair is the Seal of Maine, on which the latin word Dirigo, meaning “I lead” is emblazoned. Welch only demonstrated to his colleagues how to posture and escalate a situation. The irony ceases to matter when the outcome was so violent.

Independent experts and everyday folk can see that if spit born Hep-C was the real issue here then the spit mask should have been put on long before Welch whipped out his Mark-9 canister. And to be honest, wouldn’t anyone spit after pepper-spray to the face?

Scandalous.

Welch was ordered to take a personalised re-training program except the MDOC sent him away: It had nothing to teach him as he had already taken all recommended courses to the highest qualification. Didn’t seem to inform his conduct in this case, though.

After the episode, Schlosser was sent for a time to Maine State Prison in Warren for mental health treatment and returned to the Windham prison, where he is now in the general population. He said he is doing much better and has had no further encounters with Welch, although they see each other regularly.

Laura Schlosser, mother of inmate Paul Schlosser, watches the video Tuesday, March 12, 2013 of an incident involving her son and Welch. Shawn Patrick Ouellette/Portland Press Herald.

Antoine Ealy, Federal Correctional Complex, Coleman, Florida

You all know I’m a big supporter of Alyse Emdur and her six year project Prison Landscapes, so it was great to feature her work on Wired.com.

It’s gratifying when my interest in prisons overlap with wider issues of visual culture and with the curiosity of mainstream readers.

The article coincides with Emdur’s book Prison Landscapes, published by Four Corners, London is now available. Alyse Emdur is very grateful that Four Corners will donate books to each of the individuals whose portraits feature in the book.

Please read my piece about Emdur on Raw File.

ELSEWHERES

Prison Visiting Room Portraits, An Interview with Alyse Emdur. (Prison Photography)

Escapist Landscape Art From Inside America’s Prisons: The paintings that hide and decorate the lives of the incarcerated. (The Atlantic)

Up Against The Wall: Prison Snapshots. (New York Times)

‘Prison Landscapes’ and the Interior World of the Incarcerated. (KCET)

“I imagined you’ve seen lots of prison everything so it’s a bit intimidating to send you anything for fear I’m just repeating,” said the anonymous tip off in my inbox. The link was to a film entirely new to me. It blew me away and will you too.

Jonathan Borofsky, famous in recent years for a bunch of monstrous sculptures of 2-D men (usually hammering the air), made Prisoners in 1985. It’s one of the best prison films I’ve seen, mainly because Prisoners doesn’t weave too persistently one particular tale or one particular journey. To be reductive, I’d argue that this is the unique artist’s treatment of the subject in stark contrast to the straight documentarian’s treatment.

Generally, prison documentaries are often about trial and adversity; they necessarily have to depict struggle and hope from all angles. In other words, documentaries are often part-advocacy and answers. Borofsky just had questions. The answers the 32 California prisoners had for him in interviews will stay with you.

Part horror testimony, part philosophy, part confession, part therapy, Borofsky’s Prisoners is a tour de force. It was made in the mid-eighties just as the era of mass incarceration took hold. Back then prisoners had the same issues – poverty, drug addiction, histories of childhood abuse and adulthoods of transgression, bad circumstance and bad choices – there were just fewer of them.

The opening of the film includes atmospheric music and cuts of the more bizarre statements. It jolts. But don’t think Borofsky is setting these men and women up for a fall. Yes, his artistic hand is all over this, but he gives each of the prisoners plenty of time to pierce through our bullshit and take us right to their reality. If it seems weird, it is probably because Borofsky’s subject live weirdness every day. Borofsky let’s them speak. He shows their common institutionalisation but does not pity them.

Hugely compelling.

© Mark Murrmann, from the series, Invitation To A Hanging.

Two very potent articles published in Guernica Magazine have impressed recently.

First up, Ann Neumann details the heavy-handed force-feeding procedures by prison staff in response to the longest ongoing hunger strike in America.

The Longest Hunger Strike: American courts recognize rights to refuse life-saving treatment. So why won’t the State of Connecticut let William Coleman die?

“Staff turned off the video camera typically used to record medical procedures. They strapped Coleman down at “four points” with seatbelt-like “therapeutic” restraints. Edward Blanchette, the internist and prison medical director at the time, pushed a thick, flexible tube up Coleman’s right nostril. Rubber scraped against cartilage and bone and drew blood. Coleman howled. As the tube snaked into his throat, it kinked, bringing the force of insertion onto the sharp edges of the bent tube. They thought he was resisting so they secured a wide mesh strap over his shoulders to keep him from moving. A nurse held his head. Blanchette finally realized that the tube had kinked and pulled it back out. He pushed a second tube up Coleman’s nose, down his throat, and into his stomach. Blanchette filled the tube with vanilla Ensure. Coleman’s nose bled. He gagged constantly against the tube. He puked. As they led him back to his cell, the cuffs of Coleman’s gray sweatshirt were soaked with snot, saliva, vomit, and blood.”

““I have been tortured,” he would say later. And it was enough to make Coleman start drinking fluids again. For a while. When he stopped a few months later, the prison force-fed him again, and twelve more times over the next two years. By last year they could no longer use Coleman’s right nostril. A broken nose in his youth and repeated insertion of the tube have made it too sensitive.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Secondly, S.J. Culver writes about his discomfort visiting Alcatraz, discussing the problems that plague all sites of dark tourism.

Escape to Alcatraz: Notes on prison tourism.

“Alcatraz Island, understandably, does not bill itself as a place to spend twenty-eight dollars to get really depressed about a country’s piss-poor priorities regarding human rights. […] I begin to think that, if the point of an authentic tourism experience (if such a thing exists) is to understand another condition closely, the Alcatraz cellhouse tour fails. The punishing repetitiveness of incarceration is utterly absent in the carefully paced rise and fall of the yarns on the recorded tour. Worse, there’s no mention of how the Alcatraz cellblock, with its dioramas meticulously re-creating midcentury prison life, might resemble or not resemble a contemporary working U.S. prison. Plenty of the visitors around me seem to think they are witnessing “real” incarceration. I sense my initial impression had more truth than I realized; what we’re taking in is closer to a film set than to county lockup.”

The gulf between the realities of prison life and museum prison narratives are sometimes more pronounced than the differences between the realities of prison life and photographs of prisons in the media.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

While we’re on the topic of prison museums, a mention of Mark Murrmann‘s photographs of Invitation To A Hanging is long overdue. You might know Murrmann as the kick-ass photographer of punk. He is also the very kind and engaged photo editor at Mother Jones.

‘Prison museums?’ I hear you say. There’s more than you think.

Prison museums and dark tourism on Prison Photography

19th Century Museum Prison Ships

Roger Cremers: Auschwitz Tourist Photography

Daniel and Geo Fuchs’ STASI – Secret Rooms

Steve Davis visits the Old Montana Prison

Hohenschönhausen, Berlin: Stasi Prison Polaroids

Philipp Lohöfener at the Stasi Prison Museum, Berlin

San Pedro Prison, Bolivia: As the Tourists, Dollars and Snapshots End the Riots Begin

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Thanks to Bob for the tip.

All I want for Christmas is more weird images.

Twelve months ago, I posted To You, Happy Christmas, From Google Image Search. I guess now that I’m revisiting the format, it’s now a holiday tradition? I don’t know if this years selection tops last. I’ll let you be the judges.

Merry seasonal cheer to one and all.