You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Visual Feeds’ category.

As you know, I’m a great admirer of photography programs and mentorships for youth. Expression in the arts gives children their voice. I’ve even wondered if the empowerment provided through self-representation could benefit prisoners.

There exist dozens of important non-profits and volunteer programs helping youth of all backgrounds, including at-risk youth, to tell their stories through photography.

Organisations such as Youth in Focus, Seattle; AS220 Youth Photography Program, Providence, RI; New Urban Arts, Providence; First Exposures by SF Camerawork in San Francisco; The In-Sight Photography Project, Vermont; Leave Out ViolencE (LOVE), Nova Scotia; Inner City Light, Chicago; Focus on Youth and My Story in Portland, OR; Picture Me at the MoCP, Chicago; Eye on the Third Ward, Houston; The Bridge, Charlottesville, VA; the Red Hook Photography Project, New York; and Emily Schiffer’s My Viewpoint Photo Initiative are exemplars of youth empowerment through photography.

One of the leading participatory photography bodies is Photovoice in the UK. It has 50 programs in 23 countries.

This holiday season, Critical Exposure in Washington DC, a youth photo workshop organisation is raising money.

Simply and brilliantly, Critical Exposure – which was founded in 2004 – gives centre stage to Samera, one of the students. Watch it and celebrate the resilience and thoughtfulness of youth. It’s uncomplicated and effective storytelling, and you will be convinced of the undoubted value of these photography programs.

Samera is a compelling voice. After describing her own situation, she makes quite a simple request. She asks that schools within the same metropolitan area have better communication. She identified a fault in the system and she asked that it be fixed so others wouldn’t have to go through the same clumsy and disappointing mal-communications between Washington school district and a charter school. It’s a fair request.

Communities we shape for better, engender growth. Youths’ enthusiasm to be raised in an encouraging environment should not be neglected.

Request: “I would like to see the downtown Chicago or the lake of Chicago it will bring me happiness to see a real nice picture of the downtown. Please! A good place to eat! Nice cars! I been locked up for 17 long years!”

Last week, I asked Where Are All The Photographs Of Solitary Confinement? In terms of evidential imagery, the question still stands. A very different but equally interesting angle to take in the inquiry into images from within solitary is to consider the imagined and idealised images that persist within the minds of prisoners.

FROM LOCKED DOWN MINDS TO TANGIBLE PRINTS

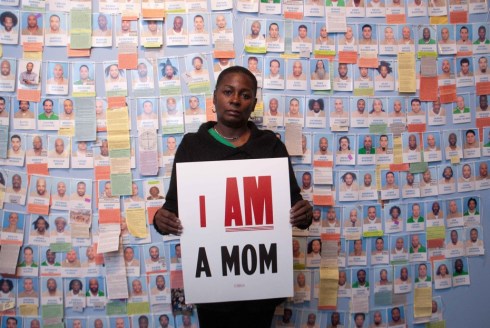

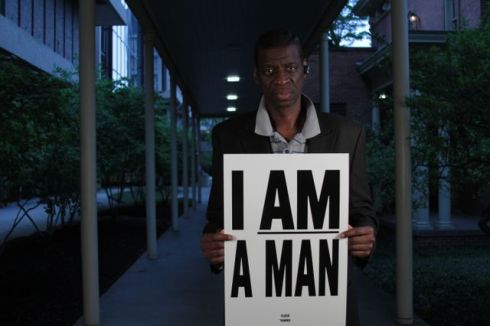

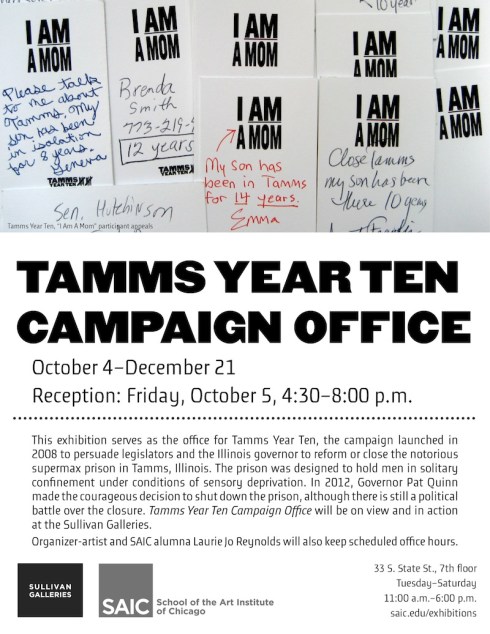

Tamms Year Ten (TY10), a Chicago-based activist group campaigning to close down the controversial Tamms Supemax in Illinois, is not only finding out what the precious images are in the minds of men in solitary, they are going out into the world and making those images a reality – making files, prints to be mailed to each man, and prints for awareness-raising exhibitions.

TY10 asked scores of men in solitary, “If you could have one picture, what would it be?” The requests can be anything in worlds real or imagined. Once made, the images are opportunities for prisoners to see what they want to, what they used to, or perhaps what they may never see again.

Tamms prisoners never leave their cells except to shower or exercise alone in a concrete pen. Meals are pushed through a slot in the cell door. There are no jobs, communal activities or contact visits. Suicide attempts, self-mutilation, psychosis and serious mental disorders are common at Tamms, and are an expected consequence of long-term isolation.

The U.N. Committee Against Torture considers such conditions to be cruel, inhuman and degrading, and when the isolation is indefinite – as at Tamms – to be form of torture. Last year, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on torture Juan E. Méndez called for a global ban on solitary confinement in excess of 15 days.

This year, Governor Pat Quinn announced his plans to shut down the prison but closure has been halted because of lawsuits by the prison guards’ union, AFSCME.

FRAMEWORK FOR CONSIDERING THESE IMAGES

Below are a selection of the requests and resulting images. They are a hodge-podge collection of styles and approaches and clearly many of the images do not meet the standards of fine art aesthetics. But, those standards are not by which these images should be judged.

The images originate from the minds of men who exist in environments of severe sensory deprivation. Each image is conjured from the absence of imagery.

Process trumps product in the TY10 Photo Requests From Solitary project. These images connect and educate people across supermax divides – the most opaque divides of prison regulation. The Photos From Solitary Project – one of the many TY10 efforts to engage the public on the issue of cruel and unusual detention – was conceived of to capture the eyes and ears of people and draw them in to protest and resistance.

The processes in making these images buttress, and spread, committed social justice activism; that is their worth.

Active in the project are artists and photographers Greg Ruffing, Oli Rodriguez, Jeanine Oleson, Rachel Herman, Claire Pentecost, Colleen Plumb, Tracy Sefcik, Harry Bos, Chris Murphy, Billy Dee, Lindsay Blair Brown, Karen Rodriguez, Sue Coe, Danny Orendorff, Lloyd Degrane and others.

Requests remain open and you can get involved too. Contact tammsyearten@gmail.com

IMAGE GALLERY

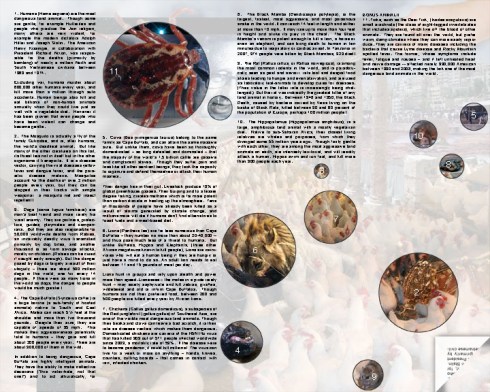

Request: “If you please, send me photographs of laser-printed image on white paper or the 10 most-dangerous land animals in the world. If you do not find it onerous and unreasonable, send me pictures of the land animals too, with a description of each animal.”

Photo montage by Mark Cooley; research and text by Stephen F. Eisenman.

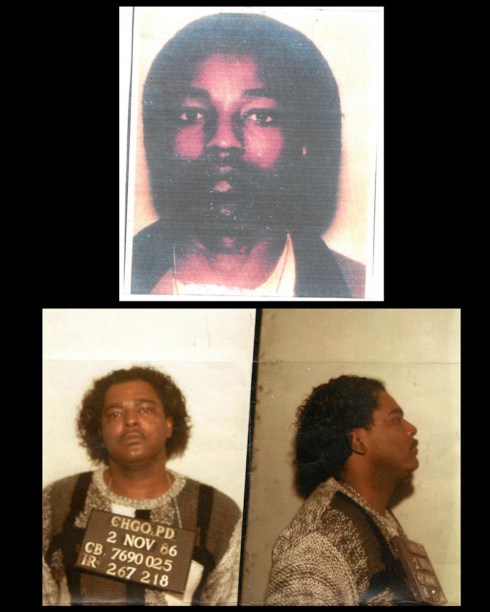

Request: “I want a photo of the whole block of 63rd and Marshfield, on the south-side in the Englewood community – the 6300 block of south Marshfield is where I’m from. I would like it taken in the day time, between two and four o’clock p.m. It’s a green and white duplex-like house – the only green and while house on the block – that my Auntie “Gibby” lives in. I want the picture taken from the sidewalk (that leads to the T-shape alley going towards Ashland and 63rd) in front of the alley, facing slightly towards 64th Marshfield. But, make sure majority of the west-side of the block gets pictured.”

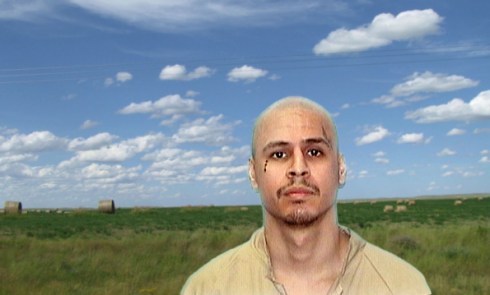

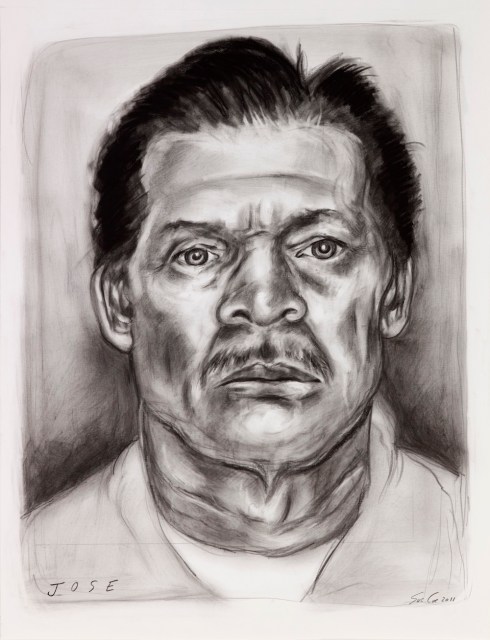

Request: “I would like my own picture done with an alternate background from the IDOC picture. I have no pictures of myself to give my friends and family. This would mean a great deal to me. If this is not able to be done. Then I’ll leave the picture for you to decide. If you can place my picture on another background. Nothing too much please. Something simple like a blue sky with clouds or a sunset in the distance would be fine.”

Request: “I would like to see a picture of a beach with the clearest water, and palm trees and birds with colorful plume, and maybe with the sun setting low on the horizon. The only instruction I have would be for you to create this photo with imagination and serenity.”

Request: “It’ll be great to get a picture of the chicago skyline at night, with all the big buildings (Willis Tower, etc) and lakefront. really I would just like pictures of the city, the x-mas tree down town, mag-mile, Mill park the places people come to chicago to see. Hey, you’re the photographer, just do what you do!”

Request: “Jennifer Lopez music videos with her ex Ben Affleck on the boat with her butt showing. I will like to see her butt.”

Request: “I would love a photograph of a woman setting by a lake fishing, with an empty chair next to her, with a cooler of beer. And in the empty chair have a sign with FreeBird on it! And have a Harley Davidson motorcycle in the background! I’d prefer the photographer take the photo from a boat out in the lake! Also, I’d prefer a woman that’s over 40!”

Request: “At 66 yrs. of age I try to use a little humor. I want a picture of a trash-can with the lid half off, with two eyes peeking out of the half-open lid. The trash can is rolling down the hill toward an incinerator with the caption: ‘I seem to be picking up speed I must be headed towards a bright future.’ I was in Florence, CO. So if you could get a picture of me in the Feds and in the state Max joints you could caption both: ‘From Max to Max and no end in sight’.”

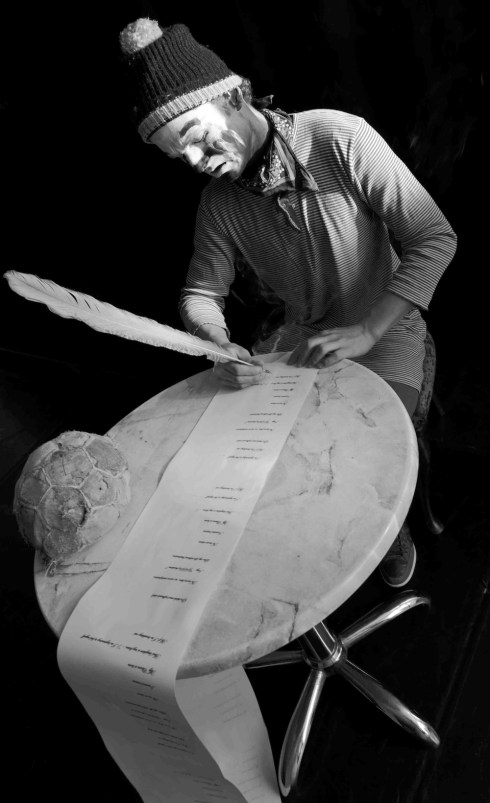

Request: “A lovesick clown, holding a old fashioned feathered pen, as if writing a letter. From the waist up, in black and white. As close up as possible with as much detail as possible, and with the face about four inches big.”

Request: “I would like this picture drawn my ID as is. Don’t add a thing. Just the face will do. Thank you for this blessing. I don’t have any pictures of myself; they all were confiscated, years back, when I was at Pontiac. So I would like to know if you could get a picture of me off the internet or the ID photo that I believe you have. Don’t worry I still don’t smile or laugh it’s been years since I smiled, but thanks to your offer I will be smiling if I get the picture your offering. I believe you could get my mug shot off the internet. The picture is to be sent to my mother in Puerto Rico.”

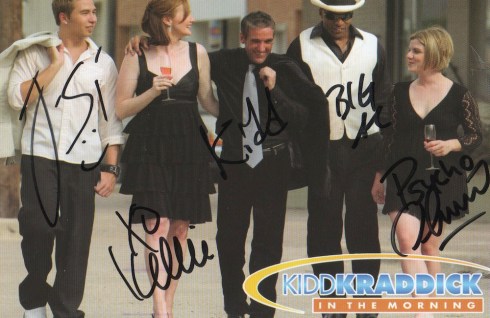

Request: “Cast of the Kidd Kraddick in the Morning Show: Kelly Rasberry; Big Al Mack; Jenna; Psycho Shannon; Kidd Kraddick; JS.” [This is the cast of the radio show he listens to every day. He has been in isolation for 12 years.]

Request: “A picture of the stone archway in the back of the yard’s neighborhood located at 40th and Exchange St; between Halsted and Racine Streets on the South Side. It’s the last remaining thing from the Union Stockyards. I used to climb up on this structure as a kid; a few angle’s of it taken from different directions. I am not limited to any photo amounts.”

Request: “I would like a photograph of Madison and Ashland looking West towards the United Center, and if you could, I would like a full frontal view of the Michael Jordan statue in front of the United Center. THANK YOU!”

Request: “A photo of my deceased mother standing in front of a mansion, or big castle with a bunch of money on the ground and a black Hummer parked in front of it. I truly appreciate this a lot. I have been trying to get a picture of this, for a long time now. Please send the picture back when you are finished. We can’t receive Polaroids, just regular pictures that is 15 pictures, but 10 per envelope. I’m sending you two poems I wrote. I would truly appreciate it a lot from you helping me out, especially as I don’t have nobody out there. Now I know somebody out there in the world cares about us in here.”

Request: “I would like to receive a photograph of a “8×10″ Puerto Rican Flag. Thank you in advance! This could be taken in the Humboldt Park neighborhood in Chicago.”

Request: “I would like a picture of downtown Waukegan, IL located in Lake County, IL. The best place to photograph would be Genesse St.”

Request: “Photographs of Tamms Year Ten – that is, if they are not prohibited. :< I’d just like to be able to put the faces to the names we’ve seen over the years so the humanity of each can shine forth – a name on paper at the end of the day is still just a name on paper!”

Request: “The Bald Knob Cross in the Southern area of Illinois with someone of the Christian faith going there praying for me with the Grand Cross in the picture praying that I am released from Tamms and that I make parole. I’ve been locked up 36 long years, and time in Tamms is hindering my chances of making parole. I am asking for intercession prayers for my release from Tamms by this personal Bald Knob Cross and the chain will cause my family and others to go there too. Be sure to include the Bald Knob Cross in the picture and to pray for my release from Tamms and to make parole. My family and church will also finish linking the chain of this event. Persistently offering prayers combined with solemn earnest efforts and devoted work to change things. God + Tamms Year Ten + dynamic team!”

TY10 note: We coordinated with the management at Bald Knob Cross, gathered his family members and others, drove six hours to Bald Knob Cross and held a beautiful litany with prayer, song and verse and every family member speaking. The next day we took family members to visit Tamms. Willie was transferred from Tamms the day before the prayer vigil! This summer – after 37 years in prison – he got parole. Willie was put on a Greyhound bus and was back in Chicago the next day. We had a Welcome Home party for him and he talked about this photograph.

Request: “A photograph within a photo of me + the lake front. A photograph within a photo of me + Navy Pier. A photograph within a photo of me + wild lions. A photograph within a photo of me + wild wolves. A photograph within a photo of me + Chinese Dragon. For next Christmas mailing of cards. Please place me in the right, upper corner of the photo within a photo and make copies of them 5 each. Thank you very much and many blessings. Get my photo off the Tamms, prison profile website.”

Request: “A photo of the Christmas tree downtown.”

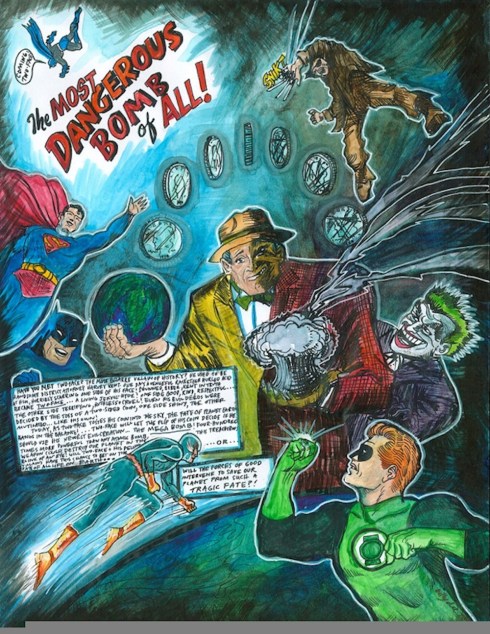

Request: “I don’t know if this like an artist drawing a picture if so I got into the whole superhero thing and I had this idea where two major comic Marvel/DC. It’s a mural with Thor, Captain America, Wolverine, Venom, Iron Man, Hulk teamed up with Superman, Green Arrow, Flash, and Batman against Two Face, Joker, Magneto, Dr Doom, Saber Tooth, Kingpin, and Green Goblin. A battle of good-vs-evil theme.”

Request: “I would like to receive an image laser-printed on regular white paper photograph a myself off the internet without my criminal convictions or other information attached to the photo. I would like the three photographs I am sending to you copied onto digital paper that can be used in a computer enhancement. If someone can do this for me, I will appreciate it very much and thank you. If you can not do it send my photos back, please. “

TY10 Note: We completed this one and the IDOC censored it and returned it to us.

Request: “I would like a photographer to capture the image of a little boy and girl, sitting side by side, on a piano bench, the two of them playing together, with a single bright red rose on the piano keys. If possible, make sure the kids are anywhere from 3-7 years old, dressed in sunday best. It shall be a romantic photo, which I hope to give to my wife. 8×10 copy of the completed photo.”

TAMMS YEAR TEN & PHOTO REQUESTS FROM SOLITARY

The exhibition Photo Requests From Solitary is on show until the 21st December, at the Tamms Year Ten Campaign Office, Sullivan Galleries, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 33 S. State St., 7th Floor, Chicago IL 60603.

The Tamms Year Ten Photos Requests From Solitary is supported by an Open Society Documentary Photography Audience Engagement Grant. In partnership with the National Religious Campaign Against Torture, the project is to expand to supermaxes in California and Virginia.

Tamms Year Ten is a grassroots coalition formed in 2008 to persuade Illinois legislators and the governor to reform or close Tamms supermax prison. Follow them on Facebook.

Isolation exercise yard, Security Housing Unit, Pelican Bay, Crescent City, California, a supermax-type control, high security facility said to house California’s most dangerous prisoners. © Richard Ross

Solitary confinement is in the news … for lots of reasons – a lawsuit brought by prisoners against the Federal Bureau of Prisons; a lawsuit brought by 10 prisoners in solitary against the state of California; a June Senate hearing on the psychological and human rights implications of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons (which included the fabrication of a replica sized AdSeg cell in the courtroom); an ACLU report pegging solitary as human rights abuse; a NYCLU report showing arbitrary use of solitary, a NYT Op-Ed by Lisa Guenther; the rising use of solitary at immigration detention centres; and the United Nations’ announcement that solitary is torture.

Recently, journalists from across America have contacted me looking for photographs of solitary confinement to accompany their article. I could only think of three photographers – one of whom wishes to remain anonymous; another, Stefan Ruiz is not releasing his images yet; which leaves Richard Ross‘ work which is well known.

Stefan Ruiz’ photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison, CA made in 1995 for use as court evidence. (See full Prison Photography interview with Ruiz here.)

With a seeming paucity, I went in search of other images. I found an image of a “therapy session” by Lucy Nicholson from her Reuters photo essay Inside San Quentin. A scene that has been taken to task by psychologist and political image blogger Michael Shaw.

Shane Bauer took a camera inside Pelican Bay for his recent Mother Jones report on solitary confinement.

Rich Pedroncelli for the San Francisco Chronicle.

Pelican Bay has been hosting media tours and welcoming journalists in the past year – partly due to public pressure and partly through a strategic shift by the CDCR to appear to be responding to public outcry. Maybe the courts have had a say, too?

© Lucy Nicholson / Reuters. Prisoners of San Quentin’s AdSeg unit in group therapy. (Source)

© Shane Bauer. Pelican Bay SHU cell. (Source)

© Shane Bauer. CA CDCR employees show investigative journalist Shane Bauer the Pelcian Bay SHU “Dog run.” (Source)

Correctional Officer Lt. Christopher Acosta is seen in the exercise area in the Secure Housing Unit at the Pelican Bay State Prison near Crescent City, Calif., Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2011. State prison officials allowed the media to tour Pelican’ Bay’s secure housing unit, known as the SHU, where inmates are isolated for 22 1/2 hours a day in windowless, soundproofed cells to counter allegations of mistreatment made during an inmate hunger strike last month. Photo: Rich Pedroncelli, AP/SF (Source)

The amount of visual evidence still seems limited. It’s not that reporting on solitary confinement is lax or missing. To the contrary, I’ve listed at the foot of this piece some excellent recent journalism on the issue form the past year. We lack images.

Look Inside A Supermax a piece done with text and not images is typical of the invisibility of these sites. National Geographic tried a couple of years to bring solitary confinement to a screen near you. ABC News journalist Dan Harris spent the “two worst days of his life” in solitary to report the issue.

Why do we need to see these super-locked facilities? Well, depending on your sources there are between 15,000 and 80,000 people held in isolation daily (definitions of isolation differ). My conservative estimate is that 20,000 men, women and children are held in single occupancy cells 23 hours a day.

Gabriel Reyes, prisoner at Pelican Bay SHU writes about his experience for the San Francisco Chronicle:

“For the past 16 years, I have spent at least 22 1/2 hours of every day completely isolated within a tiny, windowless cell. […] The circumstances of my case are not unique; in fact, about a third of Pelican Bay’s 3,400 prisoners are in solitary confinement; more than 500 have been there for 10 years, including 78 who have been here for more than 20 years.”

Solitary confinement is a “living death”; an isolating “gray box” and “life in a black hole.” Imagine locking yourself in a space the size of your bathroom for 23 hours a day. As James Ridgeway, currently the most prolific and reliable reporter on American solitary confinement, writes:

“A growing body of academic research suggests that solitary confinement can cause severe psychological damage, and may in fact increase both violent behavior and suicide rates among prisoners. In recent years, criminal justice reformers and human rights and civil liberties advocates have increasingly questioned the widespread and routine use of solitary confinement in America’s prisons and jails, and states from Maine to Mississippi have taken steps to reduce the number of inmates they hold in isolation.”

The over zealous and under regulated use of solitary confinement to control risk and populations within U.S. prisons is a cancer within already broken corrections systems. I’m posting a few more image that Google images afforded me – but I urge caution – these are just a glimpse and may not be indicative of solitary/SHU conditions. Windows are a rarity in solitary despite three images below showing them.

The main reason I’m posting here is to ask for your help in sourcing all the photography of U.S. solitary confinement we can. Please post links in the comments section and I’ll add them to the article as time goes on.

SELECT IMAGES

© Alice Lynd. Front view of cell D1-119. Todd Ashker has been in a Security Housing Unit (SHU) for more than 25 years, since August 1986, and in the Pelican Bay SHU nearly 22 years, since May 2, 1990. “The locked tray slot is where I get my food trays, mail.” (Source)

A typical special housing unit (SHU) cell for two prisoners, in use at Upstate Correctional Facility and SHU 20.0.s in New York. Photo: Unknown. (Source)

Bunk in Secure Housing Unit cell, Pelican Bay, California © Rina Palta/KALW. (Source)

Solitary Confinement at the Carter Youth Facility. Since the arrival of the girls’ program at Carter, the administration has created a new seclusion cell. This cell contains no pillow, sheet, pillow case or blanket. In fact, there is nothing in the cell other than a mattress, which was added after numerous requests from the monitor. Girls are routinely placed in this room for “time out.” Photo: Maryland Juvenile Justice Monitoring Unit. (Source)

© Rina Palta, KALW. “More than 3,000 prisoners in California endure inhuman conditions in solitary confinement.” This photo, taken in August 2011 of a corridor inside the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at Pelican Bay State Prison, illustrated Amnesty’s report. (Source)

© National Geographic. In Colorado State Penitentiary 756 inmates are held in “administrative segregation” alone in their cells for 23 hours a day. 5 times a week they are allowed into the rec room where they can exercise and breath fresh air through a grated window. (Source)

FURTHER READING

Eddie Griffin, prisoner in s Supermax prison in Marion, IL writes about “Breaking Men’s Minds” [PDF.]

Boxed In NYCLU campaign and report with resources and video against use of solitary confinement. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

The Gray Box, an investigative journalism series and film about solitary across the U.S., by Susan Greene. (Dart Society) HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

ACLU – Stop Solitary Confinement – Resources – HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

ACLU _ State specific reports on solitary confinement

Andrew Cohen’s three part series on “The American Gulag” (Atlantic)

Atul Gawande’s take on the psychological impacts of solitary confinement (New Yorker)

Sharon Shalev, author of Supermax: Controlling Risk Through Solitary Confinement, here writes about conditions. (New Humanist)

The shocking abuse of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons (Amnesty)

SOLITARY ELSEWHERE ON PRISON PHOTOGRAPHY

Interview with Isaac Ontiveros, Director of Communications with Critical Resistance, about Pelican Bay solitary and community activism.

The invention of solitary confinement.

RIGO 23, Michelle Vignes, the Black Panthers and Leonard Peltier

Chilean Miners, Russian Cosmonauts and 20,000 American Prisoners

Robert King, of the Angola 3, writes for the Guardian

Photo: Timothy Briner, from It’s A Helluva Town, in Businessweek.

THE BEST SHOT

Timothy Briner is doing the most different stuff. Whether being different will distinguish it from the crowd, we’ll see.

I was disappointed with early coverage of the Hurricane. Given the superstorm conditions photographers were getting many more misses than hits.

The biggest miss was TIME’s first dispatch of Instagram images the day after Sandy hit. Only Michael Christopher Brown of the five photographers – Kashi, Quilty, Lowy, Wilkes and Brown – had some successful frames. TIME has continued adding to its gallery of Sandy images so the older photos (31 – 57) are toward the end.

Photo: Michael Christopher Brown/TIME. Con Edison workers clean a manhole on 7th Avenue and 22nd Street in Manhattan. Source

BUT, photographers were not at fault. It was editors’ mistakes to publish below par images. Half of the photographers images I saw in the first 36 hours were from assigned photographers carrying smartphones. In low light, blustery weather the smartphones fell way short of the test.

THE MONEY SHOT

Kenneth Jarecke lays into TIME for their use of Instagram photos. Okay he references Gene Smith where there is perhaps little relevance and lists all sorts of other reasons such as Instagram getting rich of millions off other peoples’ content, but those are not the core of his burning anger. Jarecke is angry because the pictures are poor, and I can’t disagree with him. Of TIME, Jarecke says:

It’s shameful and you should be embarrassed. Not to say these shots weren’t well seen (which is the hardest part), just that they were poorly executed. Which is to say they fail as photographs.

What was weird was that in a Forbes article largely defending TIME mag’s use of Instagram images there was little discussion of the images qualities, more an emphasis on stats and page views.

Time’s photography blog, was “one of the most popular galleries we’ve ever done,” says [Photo Editor, Kira] Pollack, and it was responsible for 13% of all the site’s traffic during a week when Time.com had its fourth-biggest day ever. Time’s Instagram account attracted 12,000 new followers during a 48-hour period.

Pollack’s description of Lowy’s bland, color-field image of a wave chosen for the print magazine’s front cover as “painterly” due to its low res sums it all up; the TIME cover is known to favor photo-illustrations over straight photographs.

THE CHEAP SHOT

Sometimes articles are written as if it is still some surprise that amateur photographs shape our media and consciousness. American Photo describes the lifecycle of a viral photo.

Photo: Nick Cope. Rising flood waters as seen from the window of his Red Hook, Brooklyn apartment.

When we’re all hungry for information and we’re all sharing everything we can get a peek at then an amateur snap, if it is informative enough, will find it’s way to us very quickly.

I admire that American Photo quoted fully from this dude who got that photo.

“It was hard to track [the photo’s path to “viral”] — I was also preparing for a hurricane at the time! And for a good part of the morning I was at a cafe in the neighborhood, chatting with the owner who was mixing up Bloody Marys, and so it was a combination of hanging out with folks in the neighborhood and getting prepared for the storm. And then I start getting all these calls.”

THE TRUSTED SHOT

As ever, Damon Winter makes a bloody good fist of it for the New York Times.

The BIG Atlantic In Focus delivers with a typically epic selection off the wires. Crushed cars, boats on boats, burnt embers, friends hugging/crying, aerial shots of devastation, gas lines, strewn debris (homes), rescued old english sheepdog, destroyed pier and amusement rides, phones charging, pitch black streets, canoe in a living room, downed bridge and then this incredible picture by Seth Wenig of food being dumped.

Men dispose of shopping carts full of food damaged by Hurricane Sandy at the Fairway supermarket in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn in New York, on October 31, 2012. The food was contaminated by flood waters that rose to approximately four feet in the store during the storm. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

THE HORROR SHOT

Gilles Peress‘ very personal letter in which he appears to be having a breakdown is shared with the world.

“I have to say that in twelve years, to have shot pictures at 9/11 downtown, and again downtown in 2008 when the financial system collapsed, and now, is intense: big city, big tragedies, and a sense of having entered into a different period of history.”

I really want to know who CK and GH, the letters recipients, are.

Peress talks about homelessness and the poor being forgotten in the delivery of aid and services. Michael Shaw at BagNewsNotes wrote about the homeless being forgotten in the coverage.

Back to In Focus. Today, another good edit by Alan Taylor’s team. These two images stood out.

John De Guzman photographs a massive pile of mucky, busted furniture and appliances.

Photo: John De Guzman. A street lined with water-damaged debris in Staten Island.

John Minchillo photographed a lady who is better camouflaged than the national guardsmen beside her. I wonder what she bought at Whole Foods?

Photo: AP Photo/John Minchillo. A woman passes a group of National Guardsmen as they march up 1st Avenue towards the 69th Regiment Armory, on November 3, 2012, in New York. National Guardsmen remain in Manhattan as the city begins to move towards normalcy following Superstorm Sandy earlier in the week.

THE EVERYTHING SHOT

Everybody’s been very excited about the New York Magazine’s cover aerial photograph of a lightless Lower Manhattan.

It’s only fitting to finish these thoughts with a nod to two perhaps lesser feted Instagram photographers – after all, Instagram had record number of hashtaggles for #Sandy #HurricaneSandy and #Frankenstorm.

Wyatt Gallery has been following clean-up closely.

Clayton Cubitt is a bit more wry in his approach including this GSV comparison which is typical of Cubitt’s sideways thinking on most things visual. Good stuff.

Photo: Clayton Cubitt. Posted on Instagram, “One day you’re living the American dream. The next…”

The Day Nobody Died (detail), by Broomberg and Chanarin

SOURCE, the Belfast based contemporary photography magazine, has recently been considering how we can define (if at all) and think of conceptual photography.

The series WHAT IS CONCEPTUAL PHOTOGRAPHY is anchored by three well researched and neatly edited videos that canvas the opinions of artists, photographers, curators and critics.

I enjoyed learning about the work of John Hilliard in the first video. The surprise that conceptual photography – to which I will apply the adjectives non-figurative and self-referential – finds a welcome reception in art galleries and art festivals such as Documenta should be no surprise at all. People still expect representations of things in photography and as such representational photographs still dominate our visual culture, and especially our news culture.

The debate gets interesting is in the third video when it attaches itself to a specific body of work, The Day Nobody Died, by Broomberg and Chanarin.

In June of 2008, Broomberg and Chanarin traveled to Afghanistan to be embedded with British Army units on the front line in Helmand Province. Instead of making *traditional* photojournalistic images of the conflict, they rolled out seven metre sections of a roll of photographic paper and exposed it to the sun for 20 seconds. The Day Nobody Died is a refusal of photojournalism tropes and a question to audiences: what constitutes evidence in war, and in photography?

Broomberg and Chanarin make an effective challenge to the mechanisms at play in the embedding system – a system that routinely denies the public many accurate images of war, i.e. the wounded or dead soldier. Sean O’Hagan, photography critic for the Guardian, on the other hand, describes the project as an “arrogant” and “narcissistic” stunt.

Recommended viewing.

Ronald Day at his home in the Bronx, during a Father’s Day barbeque, held on June 17, 2012 in New York City. © Ed Kashi/VII Photo.

Inside and out of prison, people may think that to keep ones head down, survive America’s overly punitive prisons, and wait for release is enough. Unfortunately, it is not; for those looking to reenter society new struggles emerge. Each year 700,000 men, women and children are released from prisons and jails to face modern day laws and attitudes that marginalize them and limit their abilities to build new lives.

New York based non-profit Think Outside The Cell, a young but impressively effective organization, is bringing light to the struggles of former prisoners.

“The issue of stigma is not discussed enough but it is the issue of our time. The effects are so widely felt,” says Sheila Rule, Think Outside The Cell co-founder. Convicted felons are routinely denied employment, housing, access to college, the right to vote, and public benefits.

“The oppressive legal barriers and sanctions that undergird the stigma are the building blocks of modern-day inequality, keeping millions of deserving Americans on the fringes of mainstream society,” writes Think Outside The Cell.

Think Outside the Cell has partnered with the renowned VII Photo Agency to produce a multimedia campaign that will raise public awareness and educate media and policy wonks with persuasive storytelling.

“I knew about VII and their credibility,” says Rule. “It was a natural fit. We are both driven by storytelling. Stories change hearts and minds.”

Below is the trailer of the VII campaign video. The full 10 minute video can be seen here.

__________________________________________________________

In September 2011, Think Outside The Cell hosted A New Way, A New Day, a national symposium about mass incarceration. Speakers included Dr. Khalil Muhammad, director of Schomburg Center; Jason Davis, former Bloods gang leader and community activist; Jumaane Williams, New York City Council-member; Hon. Cory Booker, Mayor of Newark, NJ; Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow; Jeremy Travis, President, John Jay College of Criminal Justice; and Yolanda Johnson-Peterkin, director of operations, reentry services, Women’s Prison Association, among others. (View videos of the panels and presentations here.)

In the audience was Kimberly Soenen, a recent hire and Director of Business Strategies at VII Photo. Soenen knew that the issues of families, communities, criminal justice and inequality were of paramount interest to VII photographers. Rule, a retired New York Times journalist who knows the power of well-told and widely distributed stories, was open to Soenen’s approach to partner.

Soenen and VII focused on the immediate area and assigned New York and New Jersey based photographers to tell the stories of Ronald Day and Mercedes Smith. (With further funding, VII hopes to extend the campaign to other states.)

Mercedes Smith was released from prison two years ago. She begins college in January 2013 and although she struggles to find housing due to the rules of her parole she is making progress toward a stable life.

Ronald Day, 43, was incarcerated for 12 years, serving time in five NY institutions. Since his release, he has studied steadily, is employed connecting other former prisoners with access to services, is enrolled in the Criminal Justice PhD program at CUNY/John Jay College, and teaches criminal justice to graduate students at John Jay College.

Both Day and Smith have excellent relationships with their families.

Ronald Day’s story is not the typical tale, but that was precisely the point. VII and Think Outside The Cell wanted an optimistic view of how people can succeed in spite of the system.

“We’d always thought we’d follow someone as they were released and see them through the first weeks and months of difficult readjustment in the free world,” says Rule. But after some thought, Joseph Robinson, co-founder of Think Outside The Cell, Rule’s husband of 8 years, author, and current prisoner in Sullivan Correctional Facility, NY, suggested featuring someone who was, for all intents and purposes, succeeding, “Someone who everyone would think is doing okay, but who we could still show was facing Stigma,” posited Robinson.

While both imprisoned, Day and Robinson met at a National Trust for the Development of African American Men event. And, to this day, Rule often calls upon Day’s “dependable” organization skills to help plan Think Outside The Cell events. He was an obvious “messenger”.

However, for Day, the scrutiny of photojournalist cameras not surveillance cameras was a new experience.

“I’m not used to being followed by cameras continually. I guess that what reality TV is like. Children in the neighborhood called Ed and Ron ‘the Paparazzi.’ I thought that was hilarious!” says Ronald. “It’s good to know that my initial discomfort was a means to a higher purpose.”

Day’s motivation and higher purpose was to advocate for others.

“I want people to have a greater opportunity. You need to convince others that someone involved in a system has potential provided they’re given a chance. We need to take a second look at the individual, at the system, and the policies in ways which is fair and in ways which will change the laws,” explains Day. “I went online and looked at VII’s model for producing media. I realized it was a powerful way of producing journalism.”

And the issue is pressing.

Over the last 20 years, the number of major employers who screen for criminal records has grown to 90%. Laws that prohibit voting by people who have felony convictions deny an estimated 5.85 million Americans a visit to the ballot box. For people convicted of a drug felony, Congress has passed federal laws that place a lifetime ban on food stamps and cash assistance through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). While states can opt out of or modify the ban, most states enforce it in full or in part, says the Think Outside The Cell website.

Discrimination in the workplace is no better described as the experience of a young man who lived in D.C. and worked at a temp agency. “He was so diligent he was bestowed the Temp of the Year Award and the firm wanted to hire him full time, but when they found out he was formerly incarcerated, they fired him,” says Rule.

Furthermore, this story reflects how the stigma and laws disproportionately effect people of colour.

“Trying to figure out ‘Why’ is common to the African American experience. Was it race? Often it’s not always clear, but in some instances the reasons reveal themselves,” says Rule.

The daily limitations on former prisoners leads directly to cycles of incarceration, Robinson believes.

“It’s a cycle of stigma, collateral consequences, exclusion, and recidivism,” says Robinson. “The collateral consequences are enormous and they are not theoretical; millions are effected and it results in social, political and emotional exclusion.”

“People on parole, probation and even people 10 or 15 years out encounter difficulties achieving the basic things needed to live life – things central to being American, such as working and supporting oneself,” he says.

“High hopes and dreams can often lead to disappointment,” says Robinson. “You may have a guy who has developed a business plan, but when he goes to the bank they won’t give him a loan. There are hundreds of business licenses felons are barred from. Prisoners acquire skills in electrics, masonry, metalwork, but they can’t get construction licenses so they’re relegated to working off the books. [They are not permitted] licenses in accountancy or real estate even if their crime had nothing to do with money.”

Imprisoned for 21 years and four years from eligible parole, Robinson says he has lots of time on his hands to “develop creative ideas around social entrepreneurship.” Rule puts them into practice on the outside.

“I wouldn’t be where I am, if it weren’t for Joe,” says Rule. Although physical separated, Robinson says he and Rule are “joined at the hip” in their values.

“Social entrepreneurship is not a profit driven enterprise,” says Robinson. “I’m not saying making money is a bad thing, but the goal of social entrepreneurship is to achieve maximum impact while caring for ecology, society, people. If we focus only on profit, we can do more harm than good. NGOs, businesses, councils and governments can collaborate in social entrepreneurship.”

Specifically, Think Outside the Cell has launched a End The Stigma/Break The Cycle campaign to involve incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people; probation and parole officials; legislators and government officials; civil and human rights advocates; business leaders; labor union members; private and public employers; nonprofit administrators; students; and teachers.

Robinson and Rule are also keen to engage print and screen advertisers, which shows a canny regard for how social attitudes are shaped.

“While we are building a coalition of those who effect what we decide – legislators, officials, voters – we also want to involve people who decide what we think – those in media and advertising,” says Rule.

Meanwhile, the onus is on imprisoned individuals themselves. Day often quotes to a 19th century saying he discovered in Scott Christianson’s book With Liberty for Some: 500 Years of Imprisonment in America.

‘Very few individuals are ever rehabilitated in prison, and none are truly rehabilitated by prison. But some may rehabilitate themselves in spite of prison.”

The key to Day’s shift in fortunes was education and it is a subject he speaks passionately about.

“One intervention in the cycle of crime is access to education,” he says.

But access was curtailed in 1994 when Federal law prohibited prisoners from access to Pell Grants. State laws replicated the Federal laws. And there are other laws to reverse, too. Mandatory minimum sentencing, particularly for drug crimes, was hugely damaging. Day describes the sentences resulting from new 3-strikes laws in the 1990s as “cruel” and “disproportionate” punishment.

“The war on drugs failed,” says Day. “As Michelle Alexander points out, if you put someone into a drugs program instead of imprisoning them, you get better results. You can’t incarcerate your way out of the problem. Even conservatives recognize that. This is an ideal time; this is the most pressing of times.”

His role as a VII photographers’ subject is not without its complications for Day, but the ensuing wider conversation is worth it. His students and fellow PhD classmates do not know of his former incarceration.

“Once the VII Photo begins its series, there’s a chance they’ll find out and then we’ll have that conversation,” he says. “Often people say, ‘I’d never had guessed’ and then pepper me with questions. I often find I become a resource and that really effects the conversation.”

Bring on the conversation. With wide-eyes and courage.

“Society likes to imagine these problems don’t exist. Out of sight, out of mind. We have to deal with this. Yes, these are people who have breached the social contract, but we need to think about how we treat people after they’ve served time in prison and their debt to society,” concludes Robinson.

Rule and Robinson both acknowledge their work is in its infancy but have faith in, and knowledge of, how to tell compelling stories.

“It’s been a long and enriching experience. I have no illusions, but when most people hear our stories, they say, ‘I didn’t know’. I hear it over and over again, and then I hear, ‘What can I do to help?'” says Rule.

“Some people hold the ‘Once a convict, always a convict’ attitude, but others – and I’d say this is the majority of people – don’t know about the issues for the formerly incarcerated,” says Rule. “Think Outside the Cell campaigns and describes experiences creatively. The standards methods have no effect; creativity moves the dial.”

Ultimately, VII Photo is continuing Think Outside The Cell’s track record of telling stories with compassion.

__________________________________________________________

Editor’s note: This article is the first of a five-part Prison Photography series which will examine the nature of the VII Photo/Think Outside The Cell partnership, canvas the photographers’ thoughts and hopefully add to the push toward a fairer treatment of former prisoners.

Part Two: A Conversation With Ron Haviv

Part Three: A Conversation With Ed Kashi

Part Four: A Conversation With Jessica Dimmock

Part Five: A Conversation With Ashley Gilbertson

In the kitchen of his Brooklyn home, Ruiz flicks through his “portfolio” of prison images.

Stefan Ruiz has made photographs inside San Quentin State Prison, Soledad Prison and the notorious maximum-security Pelican Bay State Prison. His photography from within California’s prisons was not accomplished by conventional methods; at no time was Ruiz on press assignment; making documentary work or running a photography workshop.

Ruiz worked for seven years as an art instructor at San Quentin, during which time he regularly made photographic records of individual artworks. He took some portraits of his students on the side. He got inside Pelican Bay as a court-appointed photographer making photographs for use as trial evidence.

It’s a bit of a family affair. Ruiz’s mother, a professor at UC Santa Cruz, was teaching art at Soledad. Ruiz had studied Islamic art in West Africa and went to deliver a talk to Muslim prisoners at Soledad. He delivered the same lecture later at San Quentin, at which time he was introduced to the art program coordinated by the William James Association.

Ruiz’s father is a criminal defense attorney, who in the mid nineties represented a prisoner at Pelican Bay. Ruiz was the case-for-defense’s chosen photographer, documenting conditions the of client’s confinement.

In addition to his photography, Ruiz made sketches, collected his students’ artwork, and acquired objects typical of prison culture. When he showed me a photograph of a DIY prison tattoo gun, I asked, “Is that something an inmate showed you or is it something that had been confiscated?”

“It’s something I have,” Ruiz replied.

The first photos Ruiz made inside were portraits of Soledad prison-artists holding their work. He took six rolls of film. At the age of 23, Ruiz began teaching art at San Quentin. One of his students had been a student of his mother’s at Soledad years prior. Prison-art hangs in Ruiz’ house and he has collected mug-shots for years.

In the mid-nineties, Ruiz cobbled together a photo “notebook” of his pictures of people and vernacular art. He keeps it in an old Fujifilm box bound with packing tape. “I used to take this with me everywhere; it was my portfolio.”

From humble and organic beginnings, Ruiz is now one of the most respected portrait and editorial photographers in America. Until recently he had never spoken about his experiences in California’s prisons. We sat down in his kitchen to unpack his memories and his homebrew portfolio.

Q&A

PP: Your mother introduced you to prison-life?

SR: My mother organized exhibitions of the prisoners’ artwork. I helped out by taking photos of the artwork and making slides of their work. Some of that would go to William James Association to help them appeal for funding or for entry into competitions. That’s how I got cameras into the prison at first. Whenever I took a camera into a prison it was legal, and it was generally to photograph some type of art object.

PP: Of your prison work, it is your portraits that are known, however minimally, in the public sphere. I wasn’t aware of them until you were featured on VICE TV’s Picture Perfect.

SR: There are more photographs than just portraits. I taught at San Quentin for so long, and my boss had such a good relationship with the officials that gave access, that we were allowed to do quite a few things.

The first portraits I did were of the guys in my mother’s art class at Soledad who were to be involved in an exhibition. The way we were allowed to make portraits was to say, since they couldn’t make it to their show, their portrait would.

Prisoner art

Prisoner art

PP: Describe the art program.

SR: My boss played bass and the main emphasis of the art class was music but there were two visual artists who taught and I was one. The other was Patrick Maloney, who I guess is still teaching there. Patrick would also teach on Death Row. Sometimes, I would fill for him or accompany him on Death Row.

PP: How did you find working on death row?

SR: You move along the tiers and talk [through bars] to students individually, whereas on the mainline they come out their cells and they come to you.

There are two different sections of death row. In the first, there are a couple of tiers of just death row inmates. You’d need the key to get on the tier, and then you’d go from cell to cell, depending on who was part of the program. There might be three or four guys on a single tier. They had to buy their own supplies but through William James we also gave them supplies. Mostly you’d spend time talking to them. Each day, they might get half an hour outside their cell.

In the other section, the prisoners could leave their cells and go to a common space with some tables. There you could have two or three people in the class. That seemed like a better place to be on death row. The tiers are quite dark. Five tiers. And the other side is just open. One of our students was executed. He had killed a shopkeeper and his wife robbing a store in Los Angeles. He was a good student.

PP: Your mother was a professor at Santa Cruz, teaching art classes at Soledad. Those two institutions have a long and significant relationship going back to the protests and counter culture of the late sixties, Black Pantherism, and the book Soledad Prison: University of the Poor (1975) which was a collaboration between UCSC students and prisoners at Soledad.

PP: You gave a talk to Muslim students at Soledad, then to Muslim students at San Quentin and then you began in the art program. That trajectory explains your path but not your motivations. Why did you decide that leading arts education with prisoners was something you wanted to commit to multiple times a week, and eventually over seven years.

SR: Because it is interesting. I have to say; I think I learnt more from them than they learnt from me.

My father is a lawyer in criminal defense and labor law. His family is Mexican and he’s pretty liberal, so I grew up with that element too. Teaching art in prison was an activity that brought together both sides of my family.

PP: A context in which prison teaching is not a radical act?

SR: My mother was more or less a hippie. My father couldn’t really be one, he was just trying to assimilate, but he was definitely liberal. Growing up in Northern California at that time it was more of a norm than not to be on the left. To do things such as teaching in prison was not considered wild. There was no whole movement about victims’ rights as there is now.

Fair enough. There’s a lot of bad people in prison and some people who deserve to be there but …

When I was a kid, my parents were involved in a free school. We grew up in the country growing organic food. That was way before the trends of today. We composted everything; we weren’t allowed to have plastic bags for lunch. We had wax paper and baked our own bread.

The thing is the prison was interesting to me. At San Quentin they allowed me to take keys. The room where I taught art used to be a laundry room. There was a bunch of people that got murdered there, I guess in the seventies or eighties so they closed it down and eventually opened it up as an art room.

There was never a guard in our room. It was two levels but we would teach on the lower level. The closest guard was in what we would call the max-shack – a checkpoint, probably about 30 yards outside the door. I was really young when I was teaching there and a lot of the guys were way bigger than me. It was interesting to learn how to navigate that. There were anywhere from 5 to 15 people in my class. 15 would be a little bit hectic. Often we’d just get someone from the yard and have him come and sit. Students who wanted could draw him, and if not, they could work on other projects.

PP: Were any of them reluctant to paint or draw other prisoners? My experience teaching art in prison was that collectively they decided it was “suspect”, for want of a better term, to spend the time and energy painting another prisoner. Most of them made portraits of wives, girlfriends or children in a devotional way so to paint another prisoner made no sense to them and was in fact considered strange. They felt other prisoners would misconstrue it as a gesture of adoration or romantic attraction to the subject and that is something most guys wanted to avoid.

SR: No, most of them were into it. They didn’t have to do it but one thing is that since cameras aren’t allowed in prison you can make money if you can draw well, by drawing portraits, usually by copying photographs of prisoners’ family members. If you’re good you can make money. It’s like a throwback to an era before the camera; I can draw fairly realistically and that kind of saved me when I was in there because …

PP: … there’s a lot of respect attached to that ability.

SR: Yes. They’d give me a lot of shit and then we’d start drawing and it’d be fine. I generally had quite a few lifers in the class, because they are the ones who are more serious – eventually they decide to try and use their time. Young guys, who were only in for a little while, might joke around. The older guys kept the class in order.

PP: At what other times did you use your camera?

SR: There’s some really famous murals in San Quentin. I photographed them all.

PP: Was that the San Quentin administration that asked you to do that, or was it William James or was it self-initiated?

SR: My boss, Aida de Arteaga and I, decided it was a good thing to do. There are four dining halls. It used to be one huge one but it was divided because they were worried about riots. Three walls. Six sides on which the murals were painted. A Mexican-American inmate who had been busted, I think, for selling heroin painted the murals in the fifties. When I was still there, he came back to San Quentin, for the first time since his incarceration.

Photos from the San Quentin Prison dining halls. One of Ruiz’ students stands in front of the famous murals.

PP: In Photographs Not Taken you close with a bittersweet statement in which you said while you managed to take photos you still thought about the ones you weren’t allowed to take in such a “visually rich environment.” Did the staff or inmates think of their environment as visually rich?

SR: Obviously, most of the prisoners wanted to be out of there. I’m sure quite a few of the guards would like to have taken photos. Some did. Various guards had cameras for different reasons.

PP: What reasons?

SR: To photograph events. I photographed some of those too. We had concerts in the main yard, which is pretty impressive at San Quentin when you are down there with all the inmates. One time we had Ice Cube come in. On that billing, they had a white performer, a Hispanic performer and Ice Cube was the black performer. The administration has to play it like that.

Ice Cube performed in one of the dining halls and that was pretty crazy. You could see the guards were quite nervous. Some of the inmates were getting fired up. I don’t think they had another concert like that.

The prison liked the art program quite a lot and there were some guards who were supportive of our classes. Guards will either make things easy or hard for you. Basically, I think we were lucky for a lot of the time; we had people who were kind, trusted us, let us do more.

The thing about being there for so long is that you got know people fairly well. Especially being in a classroom when you’re with students for three or four hours at a time just drawing and talking. The thing that struck me was that I had a few guys who were lifers and had been in for 20 to 25 years; that’s a pretty crazy concept, especially now given all the changes that have happened, specifically with technology. I am sure – unless they were using them with their jobs within the prison – none of them had used a computer.

PP: Did you ever think there was an opportunity for you to do a photography workshop?

SR: The administration didn’t want us to do that at all. Even toward the end, they started to question me taking drawings out of the prison because many of them were realistic to the point that you could identify people in the drawings!

PP: What did the administration think of the portraits you did manage to take?

SR: They didn’t see most of them. They had signed-off on me doing photography, but they didn’t necessarily see the photographs. We got releases form the guys too. Guards might follow me round for a while, but I can take photos for days and bore the shit out of anyone. [Laughs].

I’ve probably got one of the best [records of the murals]. They were done on 4×5. I even did some on 8×10. I got in there at different times. Once, I’d used a Linhof 617 lens and camera on a commercial job, then I got access and so I used it in the prison.

PP: Did I hear that the Smithsonian has come to some sort of agreement, where by if and when San Quentin is demolished, they’ll remove and preserve the murals?

SR: They’ve been saying that for years, but I don’t know. The murals depict the history of California. The prisoners love the cable-car because the perspective is right so as you walk around it works.

“This guy before he took his shirt off warned me that his tattoos were considered some of the most racist in the prison. There’s the SS helmet skeletons.” Tattoos read ‘100% Honky’ and ‘Aryan’.

Ruiz used a chalkboard as a backdrop, “I liked the color and I liked the reference to education.” Some prisoners shaved their heads ready for the shoot. “They knew I was bringing in the camera so they prepared,” says Ruiz.

PP: It seems like the prison administration’s policy toward camera use was ad hoc?

SR: I photographed in Pelican Bay and Tehachapi, but I actually did that through a court order. My father was representing a prisoner who the CDC said was one of the heads of the Northern Mexican mafia and that he was ordering murders from his cell in Pelican Bay.

In Pelican Bay I had to use the prison’s cameras; they wouldn’t let me take in any of my own equipment, except film. This was 1995. They held on to the film, processed it, and then gave everything to me, negatives and all. The images are a bit … the lenses were a bit crazy. It’s not what I would’ve used but it was fine.

In Tehachapi, I got to use one camera and one lens. Both were mine.

PP: What was your brief for the court order?

SR: I had to photograph the cells and so the reason these photos are joined together is that they only allowed me the one lens.

Ruiz photographs of Pelican Bay State Prison, CA made in 1995 for use as court evidence.

4/4/95, Pelican Bay – “The defendant was in one of these cells.”

“Pelican Bay is obviously freaky.”

“This is the yard at Tehachapi. This is a common area, these are the cells.”

PP: It’s because of the connection through your father that you got the court ordered gig?

SR: As a defense attorney, he was allowed to bring in his own photographer. As an art teacher, I’d actually spent more time inside of prisons than my father had. Normally, he would only go to a visiting room where he would talk to his client. Whereas, I used to go on tiers, I went in cells. There were times at San Quentin when I was totally unsupervised and there were times it felt a little freaky.

PP: Were any limits placed or pre-agreements made by the courts on your photographs to limit their circulation, or are they just yours?

SR: They’re just mine.

PP: Is there a reason why you’ve not shared them widely yet?

SR: There are some that I considered might be a bit sensitive and I didn’t want to get my boss into trouble in any way. The photographs from Pelican Bay and Tehachapi are fine. The ones from San Quentin; she’d help me get the camera in. We had an understanding. I wasn’t going to screw her over.

It’s more important for me to be cool with her than it is to profit from the photos. I’ve done fine with photography without having ever shown these. I probably could’ve done a book with these and with some of the writing and artwork I have a long time ago, but I’ve never been about just promoting myself at all costs without taking others into consideration.

By now, enough time has passed. I’m going through everything. I think I have enough for a book. I have boxes of stuff that just accumulated.

PP: How did all of this work and exposure across three Californian prisons inform the rest of your career?

SR: I always knew I was going to do art. I didn’t know I was going to do photography. I always thought I’d be a painter. The thing that I learned? I learnt that if I couldn’t take any photos, I would collect things!

I took my portfolio everywhere. I got jobs off of the stuff but I never let it out of my hands. You’re the first person to have photographed it, with the exception of the VICE crew who put it in their video. I’m okay with that now. I always guarded it.

I met the guys who were doing COLORS magazine in the late nineties and it definitely influenced them. It influenced their ‘Prison’ issue (June, 2002). I was actually supposed to go to Gaza for COLORS, but the Israelis had bombed the prison right before I was due to leave, so the trip was cancelled. So, I’ve definitely used this stuff to my advantage.

PP: Did you ever give prints to the prisoners?

SR: I’d give them stuff but we kept it low key because I didn’t want any trouble for the program.

PP: Did the guys you taught appreciate that San Quentin had more programs than most prisons?

SR: They liked San Quentin. It’s an old prison. It has a lot of nooks and crannies. There are weird things that go on there that you wouldn’t get in a modern prison.

There was the old hospital built in the 19th century and out of brick. It was structurally unsound after the earthquake and left empty. They’d let certain prisoners go in there at their own risk. The deputy warden or someone in authority allowed one of my students to set up an art studio in there. And he had it for a couple of years! You wouldn’t get that at a lot of other places.

PP: Your photographs form a weird mix.

SR: I’ve always thought it was valid because it was about what I could get and how I could get it.

Soledad prisoners.

PP: Do you think prison systems in the U.S. are racist?

SR: If 11% of California’s population is Black but then at least 36% of the prison population is Black something’s not proportional. That says something about this society. Obviously the system can be racist, but it is also classist. You have a hell of a lot more poor people in prison than you do wealthy people and that’s because wealthy people can afford lawyers.

There weren’t many well educated guys in my classes. They’re obviously smart guys who could do all sorts but they weren’t well educated. I had a blonde white guy who I asked him to read something one time, not even thinking that he didn’t know how to read. It was a horrible thing for him and, of course, for me. I didn’t expect it at all. After that he started taking some of the high school classes and learnt to read.

Prisons are a control thing. [Upon release] if you have people who can’t travel, can’t get housing and can’t vote you can keep a whole population controlled. You can keep a whole population one little step away from being thrown straight back into prison.

PP: So the prison system is failing?

SR: I definitely think some people should be in prison.

There was a child molester who was quite collectible. People like to collect his art. He creeped me out. He made drawings of the kids he had killed from newspaper clippings. I took photographs of them, but I didn’t know that’s what they were until he explained them to me later. He had a scrapbook and the first 20 pages were pictures of Hillary Clinton smiling and then after that it was all these pictures of kids. Innocent pictures – many of them from National Geographic, but when you know what he was about, it’s pretty disturbing.

There’s some fucked up people in the world.

But I also saw, all the time, guys in prison for stupid drugs convictions and I think that is just a waste. The three strikes law was foolish. Keeping someone in prison, which at the time cost something like $30,000 – I’m sure it’s more now – is just a waste of money. You can give people education with that money to help them get better jobs.

I used to go to the visitor center a lot. You’d see the damage being done when families would come up from Los Angeles for the day. Wives would go in and the kids would stay in the guesthouse for the day. The separation of families when they have to travel so far [to where loved ones are imprisoned] is harsh.

Obviously, I believe in education over other things. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have done what I did.

Stefan Ruiz

Ruiz was born in San Francisco, and studied painting and sculpture at the University of California (Santa Cruz) and the Accademia di Belle Arti (Venice, Italy). He took up photography while in West Africa, documenting Islam’s influence on traditional West African art. He taught art at San Quentin State Prison from 1992-1998, and began to work professionally as a photographer in 1994. He has worked editorially for magazines including Colors (for whom he was Creative Director, 2003-04), The New York Times Magazine, L’uomo Vogue, Wallpaper*, The Guardian Weekend, Telegraph Magazine and Rolling Stone. His award winning advertising campaigns include Caterpillar, Camper, Diesel, Air France and Costume National.