You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Prisons’ tag.

Scott Fortino‘s book Institutional: Photographs of Jails, Schools, and other Chicago Buildings (2005) is important because it hit the shelves two years prior to Richard Ross’ Architecture of Authority (2007).*

People tend to think of Richard Ross’ Architecture of Authority as being the authoritative (pun unintended) photographic statement on use of identical spatial psychologies across the breadth of contemporary institutions. Perhaps Fortino can, and should, disrupt that position.

Patently, the publishing date of a book doesn’t close the argument, but I think it is apt to call these two photographers contemporaries in every sense of the word.

There are differences between Fortino and Ross’ work. Fortino’s work looks exclusively at Chicago institutions, whereas Ross – powered by a Guggenheim grant – took his survey international.

Fortino has an unusual bio, working as a photographer and police patrolman. Ross, on the other hand, is a professor in photography for the University of California, Santa Barbara. Interestingly, Ross, the son of a policeman is open about his father’s influence on his work.

I’d really like to see Fortino sat down giving a commentary on his work, just as Ross has here. Better still, I’d love to see Fortino and Ross at the same table!

– – – –

Scott Fortino’s Institutional portfolio, and more here from the Museum of Contemporary Photography Chicago.

BIO

Scott Fortino is a photographer who also works as a patrolman with the Chicago Police Department. His photographs are in the permanent collections of the LaSalle Bank of Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and numerous private collections.

* The synopsis provided for Institutional: Photographs of Jails, Schools, and other Chicago Buildings by UC Press, for me, misses the mark completely. Fortino’s work isn’t about the “subtle warmth and depth” of these spaces but of the disciplinary form written in the materials, demarcation and use of these spaces.

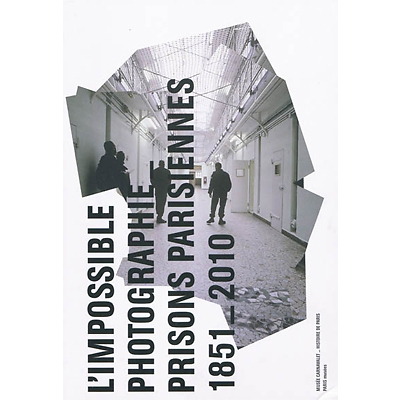

You should know by now that I am obsessed with the l’Impossible Photographie exhibition in Paris (here, here, here and here).

There is a paucity of information about the full line-up of photographers in the show, compounded by very few online images of those we do know about.

Brendan Seibel, the author of this review, and I have been exchanging emails and he has been filling me in.

First of all, many of the photographs from contemporary shooters had faces intentionally covered. This is due to French privacy laws.

There were shots of juvenile detention for which the photographer intentionally obscured faces through shutter drag or by means of scratched glass or the people covering their faces.

Other photographers shooting adults had either empty rooms, shots of people from behind, or the photos were displayed with marking tape covering the faces. Marc Feustel of Eye Curious thought it was funny, or interesting at least- I found it pretty inexcusable, particularly given the subject matter of the exhibition. Impossible Photography indeed.

I am gobsmacked! I asked Brendan to clarify. He did:

When I say tape on the pictures I mean the glass pane, not the prints themselves. Which is why I assume there’s some gallery work behind this manner of obstruction.

What!? Art-handlers and/or curators took the decision to use gaffer tape to make anonymous the portrait sitters!? Why bother using the photographs at all if you plan to deface them?

To apply tape after the fact is either a fantastic dada-turn (by artist, curator or the two in partnership) or it is the most ham-fisted exhibiting practice in recent history.

You might as well stop caring which way is UP^. What would the Art Handling Olympians say?

The three images above are not prints from the show.

They are illustrations I put together in my front room using a pane of glass, some gaffer tape and three portraits from Luigi Gariglio’s excellent book Portraits in Prisons.

Gariglio was not in the l’Impossible Photographie show.

Photo by Sang Cho.

I volunteer with the Seattle organisation Books to Prisoners. It’s a pretty awesome initiative; in 2009 it mailed 12,000 packages to prisoners across the US.

Seattle is helped by satellite groups in Bellingham and Olympia in Washington, and Portland in Oregon.

Books to Prisoners has just been presented with a generous 2:1 matching grant by a local family foundation. That means if you donate $20 it is actually a $60 donation.

If there was ever a time to donate it is now!

Books to Prisoners engages volunteers from all walks of life and has lasting relationships with student volunteers from Mercer Island High School, Seattle University, Shoreline Community College and the University of Washington.

The UW Daily just published this article – quoting my buddies Andy and Kerensa – which explains a little more about the BTP community.

The tasks are simple, the impact huge.

Books to Prisoners is a very slim and simple operation; all donations go directly to operating costs (postage, wrapping paper, tape, and occasionally purchasing dictionaries). It is an all-volunteer staff, so no money goes to salaries, staffing or admin.

There are 2.3 million prisoners in the US, a quarter of the world’s prison population. Ignoring them doesn’t make a society safer, engaging their minds does. 95% of prisoners in the US will be released at some point. It is in all our interests to treat them with dignity and provide simple tools for them to aide their own rehabilitation.

Thank you

“Curiosity was the initial spur. Surprise, shock and bewilderment soon took over. Rage propelled me along to the end.”

Jane Evelyn Atwood on photographing in women’s prisons.

This is the third and final installment in my series Women Behind Bars. The second part looked ta the writing of Vikki Law and the first looked at the journalism of Silja Talvi. It was Silja who recommended Jane Evelyn Atwood’s work.

When discussing the work of a prison photographer, it is preferable to do so within the specifics of the region or nation they document. Prison Photography‘s key inquiry is how the photographer came to be in the restricted environment of a prison and these details differs from place to place. Such inquiry is complicated by Jane Evelyn Atwood‘s work because she visited over 40 prisons in twelve countries over a period of one decade. In some cases I know the location of a particular image and in others I don’t. I suggest you compensate for this by buying the book Too Much Time for yourself.

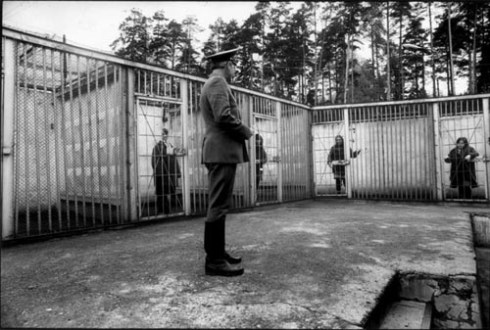

Above is a women’s penal colony in Perm, Russia. It holds over 1,000 women – the majority of who work forced hard labour. Here we see women who are in solitary confinement experiencing their yard privileges – half an hour in outside cages. Most women in the prison are there for assault, theft or lack of papers.

Below is a scene from a Czechoslovakian prison. The scars are not the result of genuine suicide attempts but of regular self-mutilation – a problem more common among female prison populations than male populations.

Another reason to pick up Atwood’s book would be that there isn’t much stuff out there on the web – and that which is is low resolution or small-size. You can see a small selection from Atwood’s Prison series at her website; small images at PoYI; and a really good selection of tear-sheets at Contact Press Images.

By far the best stuff on the web concerning Too Much Time is an Amnesty International site devoted to the project. It includes a powerful preface in which Atwood lays out her raison d’etre. Next Atwood provides a “world view” comparing the prison systems of France, Russia and the US (each a five minute audio). Then comes three specific photo-essays with audio (Motherhood, Vanessa’s Baby, The Shock Unit). Finally, Atwood provides six stories behind six photographs. The stories are many and the facts more astounding than the emotions.

While Atwood’s pictures present the many individual circumstances of the prisoners, Atwood has identified a common denominator; “Of the eighteen women I met in [my] first prison, all but one seemed to be incarcerated because of a man. They were doing time for something he had done, or for something they would never have done on their own.”

Atwood qualifies this, “One woman told me her husband forced to set the alarm to have sex with him three times a night. She endured it for years and finally killed the man that kept her hostage. Another woman’s husband was shot by her daughter after he had stabbed her in the arm as a “souvenir”, poured hot coffee on his wife’s head for not mixing his sugar, and urinated all over the living room after one of the children refused to come out the bathroom. The woman was serving time for “refusing to come to her husband’s aid.”

What is most impressive about Atwood’s work is that it predates photojournalism’s wider interest in prisons by a couple of decades. She had at first tried to gain entry into a French prison in the early eighties. Her failure is unsurprising given Jean Gaumy of Magnum was the very first photojournalist inside a French prison in 1976.

It is a scandal that the discussion over shackling women during labor and gynecological examination continues today. Atwood captured the brutality of it decades ago.

Atwood’s work veers consciously between two reality of the women’s situation – the environment and the body.

Many of her photos share a compositional austerity. The hard angles of institutions run according to ‘masculine mathematics’ (dictating sentencing and experience) are repeated. Atwood punctuates this stern reality with flourishes of femininity … and touch.

Some may think Atwood has over-reached herself with a global inquiry and I’d be sympathetic to the point if anyone else had come close to her commitment. Even considering each prison system in isolation, Atwood’s work can hold its own. Her work in Perm, Russia is particularly powerful as it orbits closely around the issue of uniform, identity and the complications it brought to bear directly on her documentary.

At the Amnesty site, Atwood brings up many interesting points of comparison. She identifies the US system as the most sterile with a legal mandate to treat female prisoners in the same manner as male prisoners. But she also says that if there is grievance or complaint to be settled, US prisoners have recourse to do so. Such allowances are not made in France.

On the other hand, children are excluded from all but a couple of US prisons. The security threat is cited as the reason: a child inside a prison is a constant vulnerable life and constant hostage target. The claim seems a little bogus when penal systems of other countries are brought into consideration.

Atwood was interviewed by Salon about the project. She has also worked on landmine victims and talked to Paris Voice about that. Here, she talks about Canon about her work in Haiti.

Jane Evelyn Atwood

Biography: Jane Evelyn Atwood was born in New York. She has lived in Paris since 1971. In 1976, with her first camera, Atwood began taking pictures of a group of street prostitutes in Paris. It was partly on the strength of these photographs that Atwood received the first W. Eugene Smith Award, in 1980, for another story she had just started work on: blind children. Prior to this, she had never published a photo.

In the ensuing years, Atwood has pursued a number of carefully chosen projects – among them an 18-month reportage of a Foreign Legion regiment, following the soldiers to Beirut and Chad; a four-and-a-half-month story on the first person with AIDS in France to allow himself to be photographed for publication (Atwood stayed with him until his death); and a four-year study of landmine victims that took her to Cambodia, Angola, Kosovo, Mozambique and Afghanistan.

Atwood is the author of six books. In addition, her work has been including the ‘A Day In The Life’ series. She has been exhibited worldwide in solo and group exhibitions. She has worked for LIFE Magazine, The New York Times Magazine, Stern, Géo, Paris Match, The Independent, The Telegraph, Libération, VSD, Marie-Claire and Elle. Atwood has worked on assignment for government ministries and international humanitarian organizations, including Doctors Without Borders, Handicap International and Action Against Hunger.

She has been awarded the Paris Match Grand Prix du Photojournalisme (1990), Hasselblad Foundation Grant (1994), Ernst Haas Award (1994), Leica’s Oskar Barnack Award (1997) and an Alfred Eisenstaedt Award (1998). In 2005, Atwood received the Charles Flint Kellogg Award in Arts and Letters from Bard College, joining a company of previous laureates including Edward Saïd, Isaac Bashevis Singer and E.L. Doctorow.

“I thought it was about the right policies and the right principle. It is really about the money.”

Jeanne Woodford, Former Warden of San Quentin and Former Secretary of the CDC, on the California prison system.

On one occasion in the past, I drew both criticism and praise for an unapologetically emotive tone. In that instance it was on the colliding social issues of Hospitals, Schools & Prisons.

Yesterday, with Beds in Gymnasiums: Prison Guards and Prison Overcrowding in California, I feel I may have ventured into similar territory as per my thoughts on the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA). Consider this post a back up and not a back down of my previous sentiments. Consolidation is good for the soul.

So, allow me to describe two important podcasts I listened to yesterday and today and hopefully the dots will join themselves.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FOLSOM & CALIFORNIA PRISONS

Folsom Embodies California’s Prison Blues (NPR) traces the decay of the California Department of Corrections from heights I wasn’t even aware of. Apparently, in the late 70s Folsom Prison was the shining light of progressive American prison cultures. All prisoners lived in their own cells, virtually every inmate was enlisted in a program or had a job, and upon release very few of them returned. It was record envied across the US.

Today, over 4,400 men live in the facility designed for 1,800. Folsom is entirely segregated by race. Education, rehabilitation and work programs are down to a few classes with a waiting list of over 1,000. Folsom and California has the worst recidivism rate of any state – over 70% will return to prison within three years.

The real juice of this podcast is the look at the history of this situation: the lobbying millions of the CCPOA, the disguised money, the pandering and the electioneering. Jeanne Woodford, an inspiring and honest inside voice, talks about how the CDC was hamstrung by the CCPOA’s power. Her sentiments are echoed by the Secretary who succeeded her.

LEVEL OF INEQUALITY vs. LEVEL OF AFFLUENCE

For the past twelve months British comic/rabblerouser, Mark Thomas, has made sense of the global recession by interviewing ‘good’ bankers, economists and policy gurus. All of these are available via podcast.

Professor Richard Wilkinson talks about Western nations and their success/failure in providing a good quality of life for their citizens.

The theory backed up by reputable statistics (WHO and others) is that social problems are more acute in countries with the most inequality. Affluence has nothing to do with social harmony. Wide differences in affluence can destroy social harmonies.

Wilkinson notes in countries such as Japan, Sweden and Finland the richest 20% are 4 times richer than the 20% poorest. In Britain, US and Portugal the richest 20% are 9 times richer than the poorest 20%. In the more inequitable countries depression and mental health problems are more widespread; there is more friction in family life as reflected in the harshness of the unjust society. Wilkinson questions the psychological landscape of western nations and asks, “What sort of society I am growing up in? Will I be fairly treated?”

Inequality is about dominance – not reciprocity – which explains why the harshest sentencing (subjugation) exists in America – the most unequal of societies. Wilkinson goes on to discuss prison systems and how their harshness is in direct correlation with social inequality. IT’S A MUST LISTEN.

On the increase of the prison population in the US, Wilkinson quotes estimates that only 10-20% of the increase is due to increased crime.* The remainder is due to more punitive sentencing.

In possession of this information, we must think about how crime, sentencing and prisons relate to society – YES, PRISONS ARE WITHIN NOT OUTSIDE OF SOCIETY. And that said, I’ll be making a return on this blog to discussion of our exposure to, and consumption of, images of prisons and prisoners.

*Both the UK and the US have been incarcerating more and more people, while crime has been falling.

Spot us

I filmed Dave Cohn‘s breakthrough Talking Heads jam sesh in 2005. The atmosphere was electric. It was also in our front room. I knew him when he was an intern at Wired.

I was really pleased therefore when he returned to San Francisco after grad school with a head full of ideas and pocket full of cash to launch Spot.Us

Spot.Us uses a crowd-funding model to support journalism. It is “an open source project, to pioneer ‘community funded reporting.’ Through Spot.Us the public can commission journalists to do investigations on important and perhaps overlooked stories … All content is made available to all through a Creative Commons license. It’s a marketplace where independent reporters, community members and news organizations can come together and collaborate.”

In the Spot.Us early days, I suggested a Tip to the community that it produced reporting on the impact of the economic downturn on California prisons. The speculation in the wording of my tip is now outdated – even laughable. We know that the CDCr has more than struggled – it has hit meltdown. The CDCr’s fiscal crisis can only turn inmates loose without sufficient re-entry support.

The function of ‘Tips’ seems to be simply to register interest; they are pithy when compared to the ‘Pitches‘ which are constantly promoted and on the search for supporters. Spot.Us not only empowers ordinary citizens through the $20 donations it also has established partnerships with big media – most recently the New York Times for Lindsay Hoshaw’s story on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Prison Health Reporting

Prison Photography would like to encourage you all to support Bernice Yeung’s Prison Health Reporting.

Yeung explains the need for journalism, “Parolees without proper access to drug treatment, mental health and medical care could have potentially serious public health and public safety ramifications. This issue has attracted the attention of policy makers, prisons, doctors and social service providers, who are increasingly trying to connect parolees with medical care and social services upon their release.”

While my position on the broken and punitive prison system of the US is well known, I have hardly commented on the need for expanded reentry support programs.

I think public safety is a notion too easily manipulated and reduced to rhetoric when legislation is created, but it is a reality that must be objectively measured when former prisoners are released.

Yeung’s focus on the drug and mental health programs, the practitioners and clients, and their testimony is the right inquiry. Yeung’s work will crystallize the life-changing, damaging, shocking and (occasionally) redemptive effects of prisons on folk in our society. Any one of the stories she tells will be more worthy than the electioneers’ tough on crime doublespeak.

Here’s the latest from Bernice Yeung on the Spot.Us blog.

______________________________________________________

Spot.Us is a fantastic experiment and is a part of the puzzle to all of those questioning what the future of news reporting will look like. See what all the fuss is about here.

______________________________________________________

Image: The image above originally appeared in the Spot.US blog post Prisons & Public Health: Why Should You Care? It is uncredited. I am curious about the image, because I am not even convinced it is from an actual prison. I would guess that a closely-cropped black & white image including bars, an obscured face and a blinding source of outside light ticks all the right boxes for a photo illustration. Our brain is fooled by these visual cues.

In this case, the writing and the appeal are more important than the image and, if my reading is right, I understand why this image was manufactured. However, I could be completely wrong. I’d like to know the photograph’s back-story….

Jolted by photographs from this ludicrous Alcatraz Hotel in Kaiserslauten, Germany I recalled an article about prisons & jails converted to tourist accommodations. I guess it makes sense to convert solid and culture-worn stone fortresses into chic hotels such as at the Charles Street Jail/Liberty Hotel, Boston (it seems a shame to waste all that cool masonry) but a prison-theme is downright tacky.

I like the no-nonsense approach of Mount Gambier Jail in Australia which “markets its rooms as budget accommodations for cheapskates and backpackers”. Oxford Castle/Malmaison Hotel in the UK retained the open cell tiers of the prison, just adding some mood uplights for the new plastered ceiling.

Here’s an article on “Slumber Slammers” which points to the larger tawdry scene of architecture-as-theatre for those wantaway tourists whose appetite for the early 21st century now fails them.

Not to be outshone, the Japanese go the farthest in recreating the prison-spectacle with handcuffs, dungeon-krunk, lethally injected cocktails and salads that refer to incest?! Don’t quite understand the link for that last one …

I’d like to begin a discussion here about recuperation, but that is presuming there was ever an element of resistance or meaningful political opposition from these various sites. All we can say for certain is the current histories of these spaces are gradually erasing those of the past.