You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘San Francisco’ tag.

THE BACKGROUND

In one of modern politics’ most outrageous adoptions of Doublespeak, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger – in 2004 – renamed the California Department of Corrections the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.* You can see videos – here and here and here – of the press conference announcing not only a change in name, but a supposed change in the management philosophy of the CDCr.

At that time, legal challenges were being made over the adequacy of healthcare. Following the 2004 criticisms and despite the 2004 promises, consistent constitutional healthcare was not provided to the prison population of California.

The CDCr failed to deliver on both medical care and meaningful rehabilitation. To prove the emptiness of the rhetoric we can look to John Gramlich’s report for the PEW Center’s Stateline last month. Gramlich made the point, that shortly after Schwarzenegger’s rebranding the “administration cut funding for prison rehabilitation programs by about 40 percent.”

THE PUSHBACK

It’s just as well for you and I, a diligent group of California citizens have for 17 years challenged the claim on the CDC acronym and since 2004 reclaimed entirely the discarded California Department of Corrections name. The CDC works to put right misleading messages, empty words and muddy communication.

Founded in 1994, the California Department of Corrections (CDC) describes itself as “a private correctional facility that protects the public through the secure management, discipline, and rehabilitation of California’s advertising.”

Above is the CDC’s latest correction of fact and assault on complacency. From their website:

The California Department of Corrections (CDC) has unveiled a new campaign of bus shelter ads to celebrate America’s assassination of Osama bin Laden.

Released prior to July 4th, a total of ten ads in MUNI bus shelters throughout San Francisco were apprehended, rehabilitated and discharged without incident. The ten liberated ads represent each year in the long decade spanning the declaration of the War on Terror by President Bush and the eventual demise of al-Qaeda’s elusive leader.

Joining in celebration with millions of US civilians after the demise of bin Laden, the red, white and blue advertisements not only pay patriotic tribute to our country, but also celebrate the unsung history of American assassinations.

The rehabilitated advertisements are currently at liberty and seem to have successfully readjusted to public life. However, these ads will remain under surveillance by department staff to prevent recidivism and any potential lapse into prior criminal behavior.

You gotta love direct action. View more works here.

* You may have noticed I always refer to the Golden State’s prison system as CDCr; using a lowercase “r” is an simple text-based slight but it makes the point.

(Via the ever-wonderful Just Seeds Blog.)

Bob Gumpert‘s Locked and Found portraits are on show at HOST Gallery for the next month (April 7th – May 7th).

On the 13th April, there’s a panel discussion on three different projects made in, around and about jails and prisons, with Bob, Edmund Clark and Guardian writer Erwin James.

HOST’s blurb:

Gumpert’s project began with an idea to photograph a homicide detective, but quickly expanded to cover numerous other aspects of the criminal justice system. After he exhibited the work in San Francisco in 2000, he thought that was the end of it, until he received a call from the sheriff’s office. California’s oldest jail was about to close, and for Gumpert, whose photographic roots were planted in the social activism of the 70s, this was a piece of history he felt compelled to document.

“‘Old Bruno’ was built in 1934 as an example of progressive incarceration, but it had become a toxic dump of a place where deputies and prisoners where expelled. Over the years the courts had ordered its closure and finally in August of 2006 everyone moved to the adjacent new Bruno. I documented the old jail, its closing and the opening of the new one,” says Gumpert, who then sought and received permission to continue his photographic quest across six county jails.

As his work progressed, so too did his attitude towards his subjects, the majority of whom were incarcerated men (he also photographed police officers and prison guards). From an ‘us and them’ relationship, his modus operandi evolved to one of participation, as Gumpert conducted audio interviews with everyone he photographed, in a kind of reciprocal exchange: a picture for a story.

Robert Gumpert has been working as a photographer since 1974, when he documented the coal miners’ strike in Harlan County, Kentucky. Since then he has worked on a series of long-term projects, including studies of the US criminal justice system and emergency health care in the United States.

For more information contact Anna Pfab on anna [at] foto8.com or 020 7253 2770.

HOST Gallery, 1-5 Honduras Street, EC1Y 0TH, London,UK

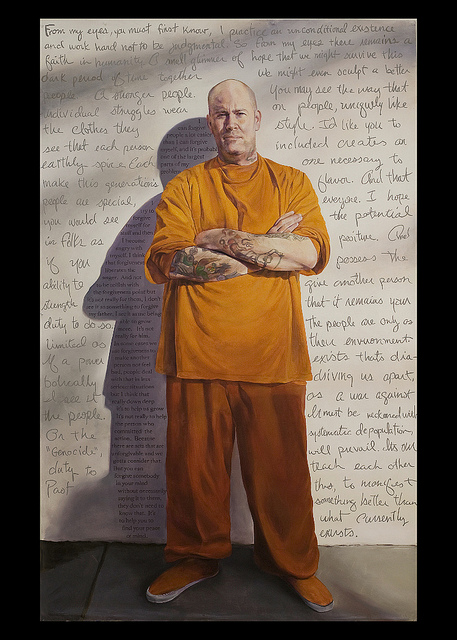

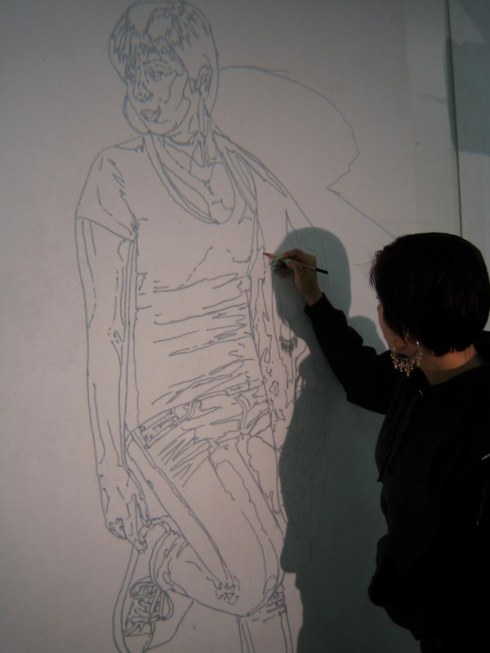

© Evan Bissell

Artist Evan Bissell brought together a group of teens who had not known each other previously, but shared a common circumstance; they were children of men incarcerated at San Francisco County Jail.

The project, What Cannot Be Taken Away: Families and Prisons Project, spanned 9 months.

Bissell and the teens shared writings and audio to establish themes for their work. Later they would visit family in SF County Jail and take photographic portraits to work from. Eventual they mounted a show at SOMArts in San Francisco.

I am a little unsure as to the ultimate claim the students have on the final product. Evidently, they decided the elements and the design, but every piece is finished with the polished painting skills of Bissell’s brush. But of course, it wasn’t only these large portraits on view; exploratory/experiential paintings of the students were displayed and the centre-piece of the show was an installation piece.

Despite the apparent dominance by Bissell over the final product, the intangibles of the collaborative project – including but not limited to discussion, new ideas, “healing & justice”, friendship, self esteem – far outweigh a critic’s (my) reserve.

I highly recommend you download the PDF time-line; it offers an impression of the shared politics of the project. Also the process describes the engagement between teacher and student.

PHOTOGRAPHY?

The tie in comes from a quote by Bissell, “I was unfortunately not allowed to photograph our workshops in the jail, so all of the pictures come from our meetings with the youth.”

© Evan Bissell

© Evan Bissell

© Evan Bissell

© Evan Bissell

© SOMArts

© SOMArts

What Cannot Be Taken Away: Families and Prisons Project. Closing September 19th 12:00-2:00 at SOMArts – 934 Brannan St. in San Francisco (at 8th Street).

All images from Bissell’s WCBTA website and SOMArts Flickr.

Source

I just came across one of Rigo‘s works in a book about prisons, but I can’t find it online so I wanted to share that which I could find.

I wondered if Rigo had done anything else. Turns out he has and he’s passionate about criminal justice abuses. Aside of his piece above in support of Mumia Abu Jamal*, Rigo has done works to rally support for America’s other most famous political prisoner, Leonard Peltier*.

Rigo also painted TRUTH (2002), an epic mural on Market Street in San Francisco, which I used to cycle past most days a without knowing its reason for being. It commemorates the 2001 quashed conviction of Robert H. King, one of the Angola 3, after 32 years of incarceration, 29 of which were spent in solitary confinement.

(Source)

* Yes, I know I could have chosen from thousands of links for Mumia and Peltier, but I chose their Twitter profiles with my eyes open to how bizarre it is. I have wondered if we live in a post-revolutionary world in which our radicals are reduced to blips of 140 characters, but then I figure the famous and infamous of the past have always survived on soundbites. I guess I ask that you use Mumia’s and Peltier’s Twitter feeds as one of many starting points for learning about their cases.

Belva Cottier and a young Chicano man during the Occupation of Alcatraz Island, May 31, 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

Today marks the fortieth anniversary of the start of the Indian Occupation of Alcatraz, an action that lasted over eighteen months until June 11th 1971.

Photographic documents of the time are surprisingly scant. Over the past few decades, Ilka Hartmann‘s work has appeared almost ubiquitously in publications about the Indian Occupation. We spoke by telephone about her experiences, the dearth of Native American photographers, the Black Panthers, Richard Nixon, the recent revival of academic research on the occupation and what she’ll be doing to mark the anniversary.

Your entire career has been devoted to social justice issues, particularly the fight for Native American rights. Did your interest begin with the Alcatraz occupation?

No, it began earlier. I came the U.S. in 1964 and that was during the human rights movement. I was a student at the time but I really wanted to go and work with the Native Americans on the reservations of Southern California. I was connected to the Indian community here through a friend who had emigrated to California earlier. I learnt very early about the conditions for American Indians. It reminded my of what I had learnt as a teenager about Nazi rule.

When the occupation began I wanted to go but I couldn’t because I was not Native American, but I waited until 1970.

Concurrently you were photographing the Black Panther movement – centered in Oakland – and the other counter culture movements of the late sixties in the Bay Area. How did they relate to one another?

They were all the same, each group struggling to advertise their conditions, the police brutality and the lack of educational and cultural institutions. I was involved in the fights for American Indians, African Americans, Chicano and Asian Americans in Berkeley. We were protesting as part of the Third World Strike. For me everything was connected and it was the same people who were speaking up later at Alcatraz.

My new book is actually about the relations between the different groups of the civil rights movement. There was a lot of solidarity between groups. The Black Panther Party understood this. Many people think that the Black Panthers were concentrated on their own politics but they understood solidarity and got a lot of help from non-Black people. If you look at my pictures of the Black Panther movement a lot of supporters were the white students of Berkeley. There is a saying, “The suffering of one, is the suffering of everybody”.

In the Bay Area people were so willing to help the Indians at Alcatraz and help in the Black Panther movement and they really felt things were going to change.

I was a student at UC Berkeley and stopped in February 1970. I went to Alcatraz in May of 1970. I had learnt to open my eyes and emotions at UC Berkeley through all the different groups we had.

How many times did you visit Alcatraz during the occupation? And how long did you stay each time?

I only went twice to the island. It is funny because I didn’t even know if my photographs would turn out. I had a camera that I’d borrowed from a friend with a 135 mm Pentax lens … and also a Leica that a friend have given me too. But I didn’t have a light-meter for the Leica so I didn’t know if the photographs I took in the fog would come out. It was so light. I was amazed that they came out. I also went over in a small boat that same year.

So I made contact sheets and tried to get them published which was a big problem because you had to really work on that. My first picture of the occupation was published in an underground paper called the Berkeley Barb then in June 1971 I was at KQED, a Northern California Television station, for an interview with an art editor. I had hitch-hiked there from the area north of San Francisco and I just opened my box of pictures to show him topics I was concerned about when over the intercom came an announcement “The Indians are being taken from Alcatraz.”

I saw some video guys run by, I grabbed my bag and camera and asked them if I could join them. They said, “Yes, ride with us and say you are with us.” We got into an old VW and drove around on the mainland to see the occupiers and that is how I got those shots of the removal. It was an incredible coincidence because I actually lived far from the city. It’s quite incredible. I only went two times during the occupation and then I got those shots afterward.

From then on I made contact with people and in that year I showed my pictures at an Indian Women’s conference, making very good friends with people in the American Indian movement. From then on I went to cultural events, powwows and so on and my pictures appeared in the underground press. I wrote articles and people contacted me for images. That’s how I made the connection.

So really you made no arrangements?

I didn’t make any arrangements. I followed everything from the first day in the papers and on that day in May … on May 30th the Indians asked all the journalists to go and I wanted to be there. That’s how it all started; they invited us there that day.

Did you realize at the time how profound an historical event it was?

Yes, I always felt how important it was. This was the first time they [Native Americans] spoke up. All over the world people wrote about it and the cause became known globally, and especially known in the United States. I believed in it … I still do.

What are your lasting memories of your time and work during the occupation?

It was a prison that had been closed so it was surrounded by barbed wire fence. Some of it had become loose and I took some pictures. The wire swung loose in the air and there was a sound across the island of the wind whispering over it. And if you looked out over the beautiful waters, you really got the sense – with the barbed wire – that the Indians were prisoners, as well as occupiers of the Bay. Prisoners of the Bay; which means prisoners of the World. In that sense I really had a strong feeling of the prison.

How did you react to the environment?

For me, strangely, the experience of going to Alcatraz has always been a very high and wonderful experience. It is hard for me to even explain. Of course I know it was a prison. On the tour of Alcatraz I got very upset, especially during the part when you’re taken downstairs to learn about the lesser known incarceration of Elders and also the cells for those people who didn’t want to go to war. So of course I know it is was a prison, yet when I go there I am struck by exuberance and hope about [Indian] people being able to make statements about their conditions.

I was a witness to that and wanted to be a conduit for those statements. There were no American Indian journalists, we were nearly all white. There was one Indian photographer, John Whitefox, who is now dead. But he lost his film. So we really saw it as our job, politically, as underground photographers and writers to cover what was part of the revolution and social upheaval.

Eldy Bratt, Alcatraz Island, May 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

Two Indian children play on abandoned Department of Justice equipment. Alcatraz Island, 1970. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

San Francisco Bay has a strange history with islands, incarceration and subjugation. San Quentin was the focus of the Black Panther resistance – it is just ten miles north of the city. Angel Island was an immigrations station for Asians – it is known as the “Ellis Island of the West” and some Chinese migrants were kept there for years. And, then there’s Alcatraz. How do you reconcile all this?

It’s totally horrible to me. I come form Germany. Before I came I’d heard about Sing Sing on the river on the East coast. It was a horrible thought to me that they could put people in such prisons.

I drive past San Quentin most days, I have actually been inside and taken photographs. And of Angel Island – it is almost sarcastic to imprison people like that; it’s such a contradiction to the beauty of the Bay. It’s the hubris of human beings to do that to one another.

Of course there are people who should be in prison, like at San Quentin, but certainly the Chinese should not have been treated like that on Angel Island. The Indians and the anti-war demonstrators should absolutely not have been treated like that on Alcatraz. Actually the authorities were respectful to the antiwar demonstrators than they were to the Indians, but still both are an aberration of human nature to treat others like that. I don’t know what to do with murderers but I do know I am against the death penalty.

An Indian man arrives at Pier 40 on the mainland following the removal in June 1971. Indians of All Tribes operated a receiving facility on Pier 40, where donated materials were stored and where Indian people could wait for boats to transport them to Alcatraz Island. Photo: © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

"We will not give up". Indian occupiers moments after the removal from Alcatraz Island on June 11, 1971. Oohosis, a Cree from Canada (Left) and Peggy Lee Ellenwood, a Sioux from Wolf Point, Montana (Right). Photo © 2009 Ilka Hartmann

How do you see the situation for Native Americans today?

When I started there was said to be one million American Indians and now statistics say there are one and a half million. This is down to two things: first, the numbers have increased, but secondly more people identify as Native Americans where they had tried to hide it before due to racism and prejudice.

I went on one trip with a Native American Family for six weeks across the southwest and I kept asking if the Indians were going to survive and there was some doubt, but now people really think the culture is growing and there has been a notable revival. There advances being made dealing with treatments for alcoholism and returning to free practices of traditional worship. I know that the Omaha are talking of a Renaissance of the Omaha culture. My friend and historian, Dennis Hastings, who was also an occupier of Alcatraz, said to me ten years ago “It could still go either way. Half the Native peoples are debilitated with alcoholism and the other half are vibrant and healthy.”

Great afflictions still exist but there are many more Indians who are able to function in the Western aspects of society and traditional ways of life. When I entered the movement there was only one [Native American] PhD; now there are over a hundred. There is hope now.

What we felt came out of Alcatraz was the influence that it had on Nixon. Because he was a proponent of the war I always used to think of him in only negative ways but that is a learning experience too. It is a shock that someone responsible for the deaths of so many people in the world, of so many Vietnamese, could do something good. He signed the American Indian Religious Freedoms Act (1978). Edward Kennedy also worked a lot on these laws.

We believe the returns of lands such as Blue Lake/Taos Pueblos in New Mexico and lands in Washington followed on from the occupation of Alcatraz. There is a famous picture of Nixon with a group of Paiute American Indians. I believe a former high school sports coach of Nixon’s from San Clememnte was Native American and so we think this teacher influenced him.

As a result of Alcatraz, as well as the land takeovers, the consciousness has been raised among non-Indians and this was very important. People in the Bay Area were very supportive of the occupation, until the point where people were not responsible; it got messy the security got too strong and there were drugs and alcohol. Bad things did happen but in the beginning all that was important to expose to the world was written about, particularly by Tim Findley and all the writers working to get this into the underground press.

Until about 15 years when Troy R. Johnson and Adam Fortunate Eagle wrote and researched their books we didn’t understand everything that had happened – we just knew it was exhilarating. We now have the information of policy changes and the knowledge of people who went back to the reservations; leaders such as Wilma Mankiller who was the principle chief of the Cherokee for a long time. Dennis Hastings was the historian of the Omaha people and brought back the sacred star from Harvard University.

Many people have done things to allow a return to the Native culture and it is so strong now – both the urban and reservation culture. American Indians are making films about urban America – part of modern America but also within their Indian backgrounds. Things have changed enormously.

The benevolence of Richard Nixon is not something I’ve heard about before!

Yes, You can read more about it in our book.

What will you be doing for the 40th anniversary?

I’l be going to UC Berkeley. I’ve been working on an event with a young Native American man who is part of the Native American Studies Program which was established in 1970 as a result of the Third World Strikes. I walked and demonstrated at that time many times. I’m very happy to be returning. LaNada Boyer Means who was one of the leaders of the occupation will be present. We’ll be thinking of Richard Aoki, who was a prominent Asian American in the Black Panther movement, who died just a few months ago.

When these people would lead demonstrations, I would photograph it and then I’d rush to the lab, work through the night to get them printed the next day in the Daily Cal and then have to teach my classes and then take my seminars and it would go on like that for weeks.

So, a young man Richie Richards has organized a 40th Anniversary celebration at Berkeley. It includes events that will run all week, films, speakers, I’ll be showing my slides and then on Saturday we’re going to Alcatraz for a sunrise ceremony. Adam Fortunate Eagle, who wrote the Alcatraz Proclamation, will lead the ceremony on the Island.

In addition at San Francisco State where the 1969 student protests originated their will be a mural unveiled to mark the occasion. There have already been recognition ceremonies for ‘veterans’ of the occupation this week in Berkeley and starting tonight there are events for Native American High School students from all over the area in Berkeley also. Interest has really rekindled recently. The text books have really changed so much and I think that is excellent for younger generations.

And many more to come …

Thanks so much Ilka.

Thank you, Pete.

_________________________________________

For this interview I used Ilka’s portrait shots from the occupation. There are many more photographs to feast on here and here.

Overcoming exhaustion and disillusionment, young Alcatraz Occupier Atha Rider Whitemankiller (Cherokee) stands tall before the press at the Senator Hotel. His eloquent words about the purpose of the occupation - to publicize his people's plight and establish a land base for the Indians of the Bay Area - were the most quoted of the day. San Francisco, California. June 11th 1971. Photo Ilka Hartmann

© Michael Jang

As far as I know, Michael Jang has not taken a photograph inside a prison … but he has been to many other altered sites.

My good friends Brendan Seibel (words) and Keith Axline (photos) did the real deal this week with an interview and gallery over at Raw File.

Blake followed a train of thought set up by Bryan this week about photography’s late-bloomers. Jang might have words of encouragement along the same lines. He hasn’t exactly had the typical career track; he was exhibiting at a high school seven years ago.

And photographs can change:

Put [a photo] away and let it age like a fine wine. … Some of the work I question, like the Beverly Hilton or the Jangs, if it would have been good when it first came out, or appreciated. I think maybe not. I think maybe you need to age 30 years so that we can look back on it.

Jang comes across as a man who has as few answers as the rest of us:

In the ’70s you could pick a subject: freaks, twins, brothers and sisters, and you’d be the first one to get it. Everyone’s done everything now. You’ve got dead body parts — we’ve done everything. So how do you carve out a niche for yourself now as a photographer? Is it more about the best person who can market themselves? The best schmoozer? The person who can make the connections? It’s a whole new ball game. I don’t know what I would do now.

Times were raw and opportune back then:

In the ’70s I happened to get a guy who committed suicide in Golden Gate Park. I knew I had the only pictures — I sold that stuff to the 11 o’clock news. But now it’s like, “send it to us for free” and you go, “yeah, I can get my name on there.” That kind of sucks for photographers making a living, right? It’s just so diluted now.

And, Jang’s response to the uncertainty? Keep shooting.

My daughter had friends that were in a band in high school and I said, “Oh man, can I shoot this?” and she said, “No! … Oh please? … No!” So what happened is they played the band shell in Golden Gate Park one day on a Saturday. Look, that’s fair game. They’re out in public. So I go there and I’m laying back; I don’t want to embarrass my kid. Eventually I start shooting and one kid kind of comes up and he starts talking to me and I end up telling him that I shot The Ramones. And that was it.

© Michael Jang

Jang also photographed around Preston, ID where Napoleon Dynamite was filmed.

Note: This one’s off topic, but I’ll be coming back with prison related visual critique sooner than you can say “Jack Lemon”.

The Computer History museum in Mountain View, California. Credit: David Glover

How do museums and galleries use online media to promote themselves?

I have been required to think about “The Museum” and it’s engagement with public and web2.0 audiences recently. If you look about you’ll find really good uses and catastrophic uses of web2.0 by museums and galleries alike. I don’t want to beat up on small galleries for their ill-advised, tweeting non-personas nor criticise lackadaisical irregular blog posting; both of these activities are for the intern. I’d really complain if I thought someone was getting paid to stumble through blog posts and ideas after a full day educating outreach audiences.

I do think the MoMA and San Francisco MoMA are fair game though.

Let’s start with the good.

MoMA: A delicate, understated film-short, with good production values. Some might argue it’s over sentimental and panders to arty self obsessions, but the MoMA is the beacon of an art world, art market and art-as-brand that has Western obsessions about the object at its core. I’ll allow it to veil this truth and remould it as individual yearning.

Click on the image below to view the video at The Contact Sheet blog.

And now, to the bad.

SFMoMA: Apparently inspired by the White House launch of Obama coverage on Flickr, the San Francisco MoMA launched its own stalking eye upon director Neal Benezra. They call it Director Cam.

Benezra at press preview, being interviewed by Don Sanchez for ABC7, in the SFMoMA rooftop sculpture garden.

Now, I am all for transparency, informality, familiarity and all that, and, to be fair, SFMoMA has done this reasonably well with its other Flickr sets (although I’d prefer less high-society party coverage and more high-school outreach coverage).

However, Director Cam just rubs me the wrong way. I don’t want to see the privileged folk of the museum-world lording over its institutions, I want to see public audiences getting knee deep in collections & archives and mixing it up a bit. I want to see Flickr used as a means to entice people into the museum not as a mirror for already existing (and exclusive) engagements.

Neal talking with Exhibitions Design Manager / Chief Preparator Kent Roberts. With Chuck Schwab, chairman of the board of trustees (center) and Catherine Kuuskraa (right). In the background on the left wall you can just slightly see the new bridge commission, by Rosana Castrillo-Diaz.

BLDGBLOG (via Twitter) this week called for an alternative narrative of the built environment.

As I understood this, it is a theoretical proposal that would include interviews and testimonies of electricians, security guards and the fixers that keep the nuts and bolts in place while arty self-obsessed types flit about amid well-maintained frameworks.

After the white-collar fraudulent dismantling of the city, there is no better time to call for an alternative version of urbanity. A blue-collar city narrative.

With these thoughts looming, it is not Benezra that interests me, rather Kent Roberts, Exhibitions Design Manager and Chief Preparator at SFMoMA. Bring on ‘Museum Preparator Cam’!

All of this throws up more unanswered questions about the role of new media in the operations of museums and galleries. Fortunately, I recently discovered Nina Simon’s Museum 2.0 blog which provides some riposte.

___________________________________________________________

Images. Computer History Museum by David Glover. As well as his Computer History Museum Set, you should check out his Byte Back Set.

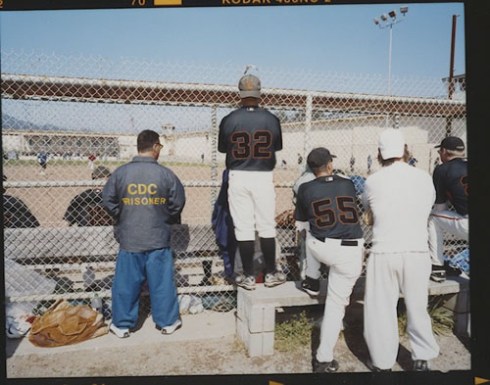

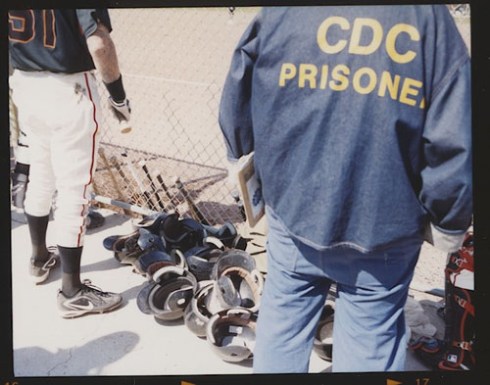

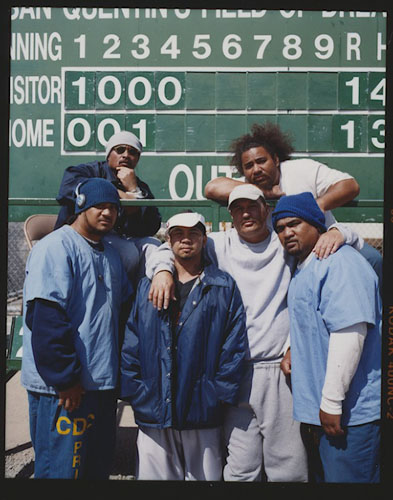

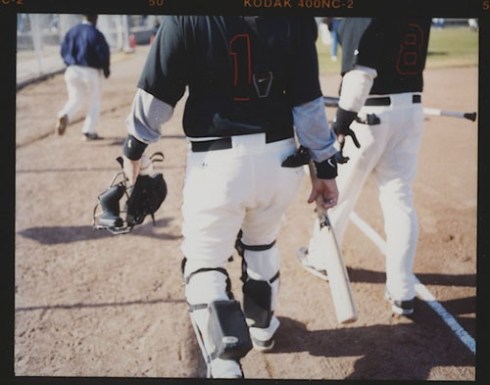

Last week, I threw up a quick post featuring Emiliano Granado’s website images of his photographs of the San Quentin Giants. Here, Granado shares previously unpublished contact sheet images, his experiences and lasting thoughts from working within one of America’s most notorious prisons.

What compelled you to travel across the US to photograph the story at San Quentin?

This was actually a magazine assignment for Mass Appeal Magazine. However, the TOTAL budget was $300, so it really turns out to be a personal project after the film, travel expenses, etc. So, the simple answer to the question is that I’m a photographer. I’m curious by nature. Part of the reason I’m a photographer is to study the world around me. I like to think of myself as a social scientist, except I don’t have any scientific method of measuring things, just a photograph as a document.

With that in mind, it would be crazy of me to NOT go to San Quentin! I’d never been in a correctional institution but I’ve always been fascinated by them. If you look through my Tivo, you’ll see shows like COPS, Locked Up, Gangland, etc. I was also a Psychology major in college and remember being blown away by Zimbardo’s prison experiment and other studies. Basically, it was an opportunity to see in real life a lot of what I’d seen on TV or read in books. And as a bonus, I was allowed to photograph.

What procedures did you need to go through in order to gain access?

I was amazed at the lack of procedure. The writer for the story had been in touch with the San Quentin public relations people, but that was it. There was plenty of other media there that day. It was opening day of the season, so I guess it made for a minor local news story.

I’m pretty sure SQ prides itself in being so open and showcasing what a different approach to “reform” looks like.

It is my opinion that San Quentin is one of the best-equipped prisons in California to deal with a variety of visitors. Did you find this the case?

Definitely. Access was very easy. They barely searched my equipment! Parking was easy. I was really surprised at how easy and smooth the process was. Not to mention there were many other visitors that day (an entire baseball team, more media, local residents playing tennis with inmates, etc).

Did your preparation or process differ due to the unique location?

Definitely. I usually work with a photo assistant and that couldn’t be coordinated, so I was by myself. I packed as lightly as I could and prepared myself for a fast, chaotic shoot. Some shoots are slow and methodical, and others are pure chaos. I knew this would be the latter.

One thing I didn’t think about was my outfit. SQ inmates dress in denim, so visitors aren’t allowed to wear denim. Of course, I was wearing jeans. The officers gave me a pair of green pajama pants. I’m glad they are ready for that kind of situation.

You are not a sports shooter per se. You took portraits of the players and spectators of inmate-spectators. How did you choose when to frame a shot and release the shutter?

Correct. I’m definitely not what most people would consider a sports photographer. I don’t own any of those huge, long lenses. However, I photograph lots of sporting events. I think of them as a microcosm of our society. There are lots of very interesting things happening at events like this. Fanaticism, idolatry, community, etc. Not to mention lots of alcohol and partying – see my Nascar images!

Hitting the shutter isn’t entirely a conscious decision. That decision is informed by years of looking at successful and unsuccessful images. It’s basically a gut instinct. There are times that I search for a particular image in my head, but mostly, it’s about having the camera ready and pointed in the right direction. When something interesting happens you snap.

There are photographers that come to a shoot with the shots in their head already. They produce the images – set people up, set up lighting, etc. Then there are photographers that are working with certain themes or ideas and they come to the location ready to find something that informs those ideas. I’m definitely the latter. There is a looseness and discovery process that I really enjoy when photographing like this. It’s like the scientist crunching numbers and coming to some new discovery.

A lot of photo editors say the story makes the story, not the images. Finding the story is key. Do you think there are many more stories within sites of incarceration waiting to be told?

I’m not sure I agree with that. I always say that a photograph can be made anywhere. Even if there is no story, per se. I definitely agree that a powerful image along with a powerful story is better, but a photograph can be devoid of a story, but be powerful anyway.

Every person, every place, everything has a story. So yes, there are millions of untold stories within sites of incarceration. Hopefully, I’ll be able to tell some of them.

Having had your experience at San Quentin, what other photo essays would you like to see produced that would confirm or extend your impressions of America’s prisons?

Man, there are millions of photos waiting to be made! I’m currently trying to gain access to a local NYC prison to continue my work and discover a bit more about what “Prison” means. Personally, I’d love to see long-term projects about inmates. Something like portraits as new inmates are processed, images while incarcerated, and then see what their life is like after prison. Their families, their victims, etc. And of course, if any photo editor wants to assign something like that, I’d love to shoot it!

Anything you’d like to add to help the reader as they view your San Quentin Baseball photographs?

Yes. When I walked in to the yard, I didn’t know what reaction I would get from the inmates. Everyone was super friendly and willing to be photographed. Everyone wanted to tell me their story. I’m not sure how different their reaction would have been to me if I didn’t have a camera, but I was pleasantly surprised. At first, I felt like an outsider and fearful, but after an hour or so, I felt comfortable and welcome. It was a weird experience to think the guy next to me could be a murderer (and there were, in fact, murderers on the baseball team), and not be afraid. There was this moral relativism thing going on in my head. These people were “bad,” yet they were just normal guys that had made very big mistakes. I left SQ thinking that pretty much any one of us could have ended up like them. Given a different set of circumstances or lack of access to social resources (e.g. education, money, parenting, etc) I could very easily see how my own life could have mirrored their life.

And finally, can you remember the opposition?

I don’t remember who they were playing, but I do remember that their pitcher had played in the Majors and even pitched in a World Series. I believe the article that finally ran in Death + Taxes magazine mentions the opposition.

ALL IMAGES © 2009 EMILIANO GRANADO

Authors note: Huge thanks to Emiliano Granado for his thoughtful responses and honest reflections. It was a pleasure working with you E!

Housekeeping. At the end of my previous post on Emiliano’s work, I postured when San Quentin would get more sports teams for the integration of prisoners and civilians. Emiliano has answered that for me in this interview. He observed locals playing tennis and also states San Quentin also has a basketball team.